By Robert F. Dorr

When the Arado Ar-234 Blitz jet bomber first appeared in the skies of Europe, most Allied airmen did not know what it was. Many had never heard of jet engines, let alone a jet bomber. Fewer still knew that the Ar-234 was a shining star in Adolf Hitler’s constellation of wonder weapons, the super-secret and super-technology arsenal that the Führer hoped would reverse the Reich’s declining fortunes.

The Allies First Glimpse at the Arado 234 Blitz

Hitler certainly never asked for an opinion from Don Bryan. At high altitude east of the Rhine bridgehead on March 14, 1945, American fighter pilot Captain Bryan was on his way home from a bomber escort mission when he spotted an Ar-234 making a bombing run on the pontoon bridge at Remagen.

At this juncture, the American fighter pilot may have known more about Hitler’s secret jet than anyone else on the Allied side. While most Allied pilots never even glimpsed one, this was Bryan’s fourth encounter with an Arado. In December 1944, he became, he asserted, the first Allied pilot ever to see one in the air.

After studying drawings of the jet in a Group Intelligence document, Bryan spotted Ar-234s on two more occasions later that month. During his third sighting, the Luftwaffe warplane crossed his flight path beneath him, flying from left to right. Bryan went after the Arado, but it pulled away. That was when he realized that while his North American P-51 Mustang fighter was fast, the Ar-234 was almost 100 miles per hour faster.

“I’m not letting one get away from me again,” Bryan thought out loud.

The Bluenosed Bastards of Bodney

The usual soup over Germany has been transformed into brilliant sunshine on March 14. Eleven of the German jet bombers from flying unit KG 76 (Kampfgeschwader 76) were attacking the newly constructed floating engineer bridge south of the Ludendorff Bridge, which was the last traditional bridge standing on the Rhine when it was captured by soldiers of the U.S. 9th Armored Division on March 7, 1945.

Bryan, of the 352nd Fighter Group, the Bluenosed Bastards of Bodney, was an air ace and commander of the group’s 328th Squadron. Bryan saw the Arado pulling off the bridge and maneuvering into a tight turn to evade a formation of American Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighters. This maneuver compromised the jet bomber’s strongest asset, its superior speed, and Bryan was able to position himself so the German would have to fly toward him.

Bryan dived at the bomber and fired a burst of .50-caliber gunfire that disabled its right engine. Now, Bryan was able to stay behind him and continue firing. “I don’t know what the hell was on his mind,” said Bryan in an interview, “but he should have gotten out of that airplane while he was high enough. I think he was afraid I would shoot at him in his parachute, which I would never do.”

The Arado pilot, Hauptmann (Captain) Hans Hirshberger, waited too long to jettison his roof hatch and attempt to escape from his cockpit. He went down with the aircraft. It was his first and only combat mission.

The Fastest Combat Aircraft of 1945

Able to reach a speed of 540 miles per hour, the Arado Ar-234 Blitz was the fastest combat aircraft in the world, slightly faster even than its cousin, the Messerschmitt Me-262 jet.

It was the world’s first operational jet bomber, and in many ways the most advanced of the Third Reich’s secret weapons. It was important enough that Hitler referred to it several times in staff meetings with his military leaders. Hitler was especially annoyed that Britain’s De Havilland Mosquito reconnaissance aircraft, constructed largely of wood, was speedy enough to zoom over Germany with near total impunity. The Führer often boasted to his staff that the Ar-234 jet was even faster than the prop-driven Mosquito.

The Ar-234 was a product of the German company Arado Flugzeugwerke. It was the Arado response to a 1940 German Air Ministry requirement for a fast reconnaissance aircraft. Walter Blume headed the Arado engineering team.

Blume had been a fighter ace during World War I with 28 aerial victories and had been gravely wounded on a combat mission. Blume could appear absent-minded at times, prickly at others, but he had studied aeronautical engineering for more than two decades and was up to date on the jet engines that some touted as the wave of the future. He was responsible for all of the key design features of the Ar-234, assisted by engineer Hans Rebeski and others.

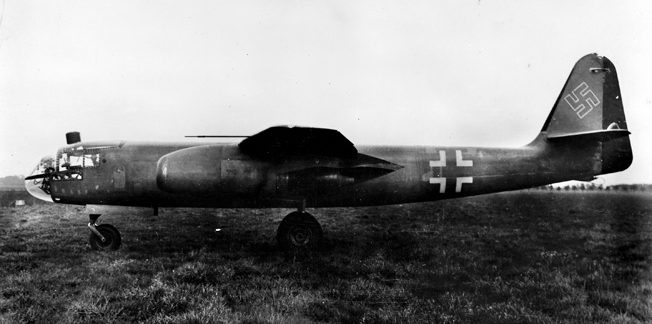

On their drawing boards, they conceived an aircraft that was extraordinarily clean. It had smooth, flush-riveted exterior skin. It had rakish lines and eventually tricycle landing gear. Where most planes needed a bulge or a step for the cockpit windshield, the Ar-234 had a completely smooth, glass-covered nose in the manner of the American Boeing B-29 Superfortress heavy bomber. The engine arrangement was similar to that of the better-known Me-262, with long, deep-throated nacelles slung beneath the inboard portion of the wing.

The design was code-named the E370, and the new aircraft was built for a projected maximum speed of 485 miles per hour, which it eventually exceeded with ease. Its projected range of about 2,000 miles was a little less than what the Air Ministry wanted, but officials in Berlin liked the design and ordered two prototypes, known as the Ar-234 V1 and Ar-234 V2.

Designing the Ar-234

The success of the new plane would be dependent on the engine intended for it. The engine was the Jumo 004 axial-flow turbojet designed by a team headed by Dr. Anselm Franz of the Junkers aircraft company. It eventually became the world’s first jet powerplant to enter production and become operational. But early jet engines being developed by the Germans and the British, with the Americans lagging a distant third in jet engine development, were cantankerous, unreliable, and trouble prone.

Design work on the Ar-234 airplane went smoothly. The Junkers Jumo 004 turbojet engine was another matter. Tests that began in October 1940 were delayed by constant technical problems, including vibration of the compressor blades. Steel blades had to be developed to replace the original alloy blades. Still, early versions of the engine sputtered, smoked, and died. One blew up on a test bench. The vibration problems continued until a second overhaul was made of the stator blade design. These and other problems delayed the engine and that, in turn, delayed both the Messerschmitt Me-262 jet fighter and the Ar-234—for reasons unclear, the latter more than the former.

Once it became workable, the production version of the engine, the 004B-1 was rated at 1,980 pounds of thrust, which was comparable to the turbojet Frank Whittle was developing for the British. Even then, the Jumo typically had a service life of only 10 to 25 hours. Like all turbojets, it was sluggish in responding to the pilot’s hand on the throttle.

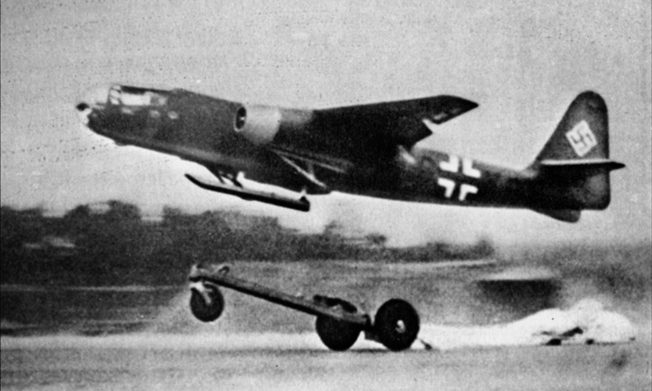

The plane’s landing gear was not part of the original design. Blume’s design team was very much aware that the Luftwaffe was not fully satisfied with the plane’s range and endurance. To increase internal fuel capacity, they initially dispensed with wheels. Early Ar-234 versions took off using a three-wheeled trolley and landed by means of skids that worked well on a grassy surface. For increased thrust during takeoff, Ar-234s used Hellmuth Walter designed liquid-fueled, rocket-assisted takeoff (RATO) boosters, one mounted beneath each wing.

A One-Man Bomber

The Ar-234 was not as large as it looked. When American ace Don Bryan first spotted one, he thought it was an American A-26 Invader. But the A-26 had a wingspan of 71 feet and was intended for a crew of three. In contrast, the Ar-234 had a wingspan of just over 46 feet. Its crew consisted of just a single pilot who, as Bryan later said, “had to be a very busy and very lonely man.”

The pilot got aboard by pulling down a retractable step on the left side, climbing up kick-steps, and entering via the roof hatch. This hatch could be discarded, but there was no ejection seat and a pilot’s prospects of getting out of the Arado under any circumstances were never good.

The pilot operated conventional throttle and rudder pedals, and clear plexiglas gave him a superb view in all directions. Between the pilot’s legs was the complex Lofte 7K tachometric bombsight. At the start of a bombing run, the pilot was expected to swing the control yoke out of his way and fly the aircraft using the bombsight control knobs, looking through the optical sight. Alternately, he could fly the aircraft using the yoke and use a periscope sight, derived from the type used on German tanks, mounted on the cockpit roof and associated bombing computer to make a diving attack. Despite the very narrow landing gear that became standard after the skids were abandoned, the Ar-234 performed well when taxiing, taking off, and landing and was not unduly vulnerable to crosswinds.

Flight Testing the Arado

Although Arado began construction of the Ar-234 prototype at its factory in Warnemunde in the spring of 1941, almost two years elapsed before the manufacturer received its first engines. No one seems to know why Willi Messerschmitt’s aircraft company was able to get Jumo 004 engines for its Me-262 in June 1942, while Arado was forced to wait for its first engine until February 1943. For months, Blume and his engineers looked at the unfinished shell of the first plane, called the Ar-234 V1, and followed reports of Messerschmitt’s aircraft undergoing flight tests.

The Ar-234 V1 prototype made its first flight on June 15, 1943, not at the factory but at the company test facility at Rheine Airfield. At the controls was Arado chief test pilot Flugkapitän (flight captain) Selle, whose first name seems to be lost to history. By September, four prototypes were flying. The second prototype, the Arado Ar-234 V2, crashed on October 2, 1943, at Rheine near Munster after suffering fire in the port wing, failure of both engines, and various instrumentation failures. The aircraft dived into the ground from 4,000 feet, killing pilot Selle.

In flight tests, there were constant problems with the takeoff trolley and the landing skids. On one flight, the pilot correctly jettisoned the trolley at an altitude of 200 feet, but its parachute failed to deploy and it was smashed. The skids often stayed in the extended position when they should have retracted, or collapsed when they should have been extended. At this rate, Arado experts and Luftwaffe officers agreed, during mass operations a typical airfield would become cluttered with disabled Ar-234s and following aircraft would be unable to land at all. Another drawback was that the Ar-234 could not taxi on the skids. It had to come to a halt and then be moved using a crane. Recognition of the need to change the landing arrangement prompted cancellation of a planned production version called the Ar-234A.

The Arado’s First Missions

Despite the problems, the Ar-234 V7 prototype became the first jet aircraft ever to fly a reconnaissance mission. On August 2, 1944, Lieutenant Erich Sommer whizzed over the Normandy beachheads at about 460 miles per hour and used two Rb 50/30 cameras to take one set of photos every 11 seconds. Although the Allies supposedly had air superiority over the beaches, Sommer’s warplane returned with unscathed.

The Ar-234B Schnellbomber, or “fast bomber,” introduced a widened fuselage that permitted conventional landing gear, albeit with a very narrow track. The B model, first flown on March 10, 1944, piloted by civilian test pilot Joachim Carl, who replaced Selle, was slightly heavier than reconnaissance versions at 21,720 pounds. Because the Ar-234 was slender and entirely filled with fuel, it had no room for a bomb bay. Its bomb load had to be carried on external racks.

The added weight and drag of a full bomb load reduced the speed, so on the B model two 20mm MG 151 cannon with 200 rounds each were added in a remotely controlled tail mounting to give some measure of defense. Since the cockpit was directly in front of the fuselage, the pilot had no direct view to the rear, so the guns were aimed through the periscope. No record exists of anyone ever hitting anything with these guns. Many pilots removed them to save weight.

It was not until June 1944 that 20 Ar-234Bs were produced and delivered. Some of these were diverted to the Luftwaffe test center at Rechlin. From October 1944, the German air unit known as KG 76 began to convert to the Ar-234B-2 bomber. The group began flying missions during heavy fighting in the Ardennes. In March 1945, coming in at low level and slinging bombs almost horizontally, after several attempts KG 76 finally succeeded in collapsing the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen, but by then the loss of the bridge had little effect.

“I liked the Arado very much,” said former Luftwaffe pilot Willi Kriessmann, who lives today in Burlingame, California. “It was a wonderful plane. I thought it was designed better than the Messerschmitt Me-262. It was a single seater, so we didn’t have time to practice much, so we had some ‘dry classes.’ Landing and taking off was very different from a prop plane.” Kriessmann noted that the RATO units often did not work properly.

224 Arados Produced

Two different configurations for a four-engined version of the Ar-234 were built and flown. The sixth and eighth planes in the series were powered by four BMW 003 jet engines instead of two Jumo 004s, the sixth (Ar-234 V6) having four engines housed in individual nacelles, and the eighth (Ar-234 V8) flown with two pairs of BMW 003s installed within “twinned” nacelles underneath each wing. These were the world’s first four-engined jets. They offered no performance advantage over the twin-engined version.

An improved Ar-234C was the final production version. This model introduced an improved pressurized cockpit and larger main wheels. A “crescent-wing” Ar-234, foreshadowing Britain’s Handley Page Victor bomber of the 1950s, was under construction but never flown.

Kriessmann was assigned to ferry Ar-234s from the factory “to different places where they installed optical equipment and bombing equipment. I flew the first one on December 12, 1944, from Hamburg to Kampfgeschwader 76 and the last on May 1, 1945.” KG 76 flew the final Ar -234 sortie of the war against advancing Red Army troops near Berlin.

Plans existed for the manufacture of 2,500 Ar-234 Blitz bombers, but they were cut short by the war’s end. Total production was 224 examples of all versions of the Ar-234.

Surviving After the War

Today, the only surviving aircraft in this series is an Ar-234B-2 bomber (werke number 140312) on display at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center of the National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, at Dulles, Virginia, replete with RATO units.

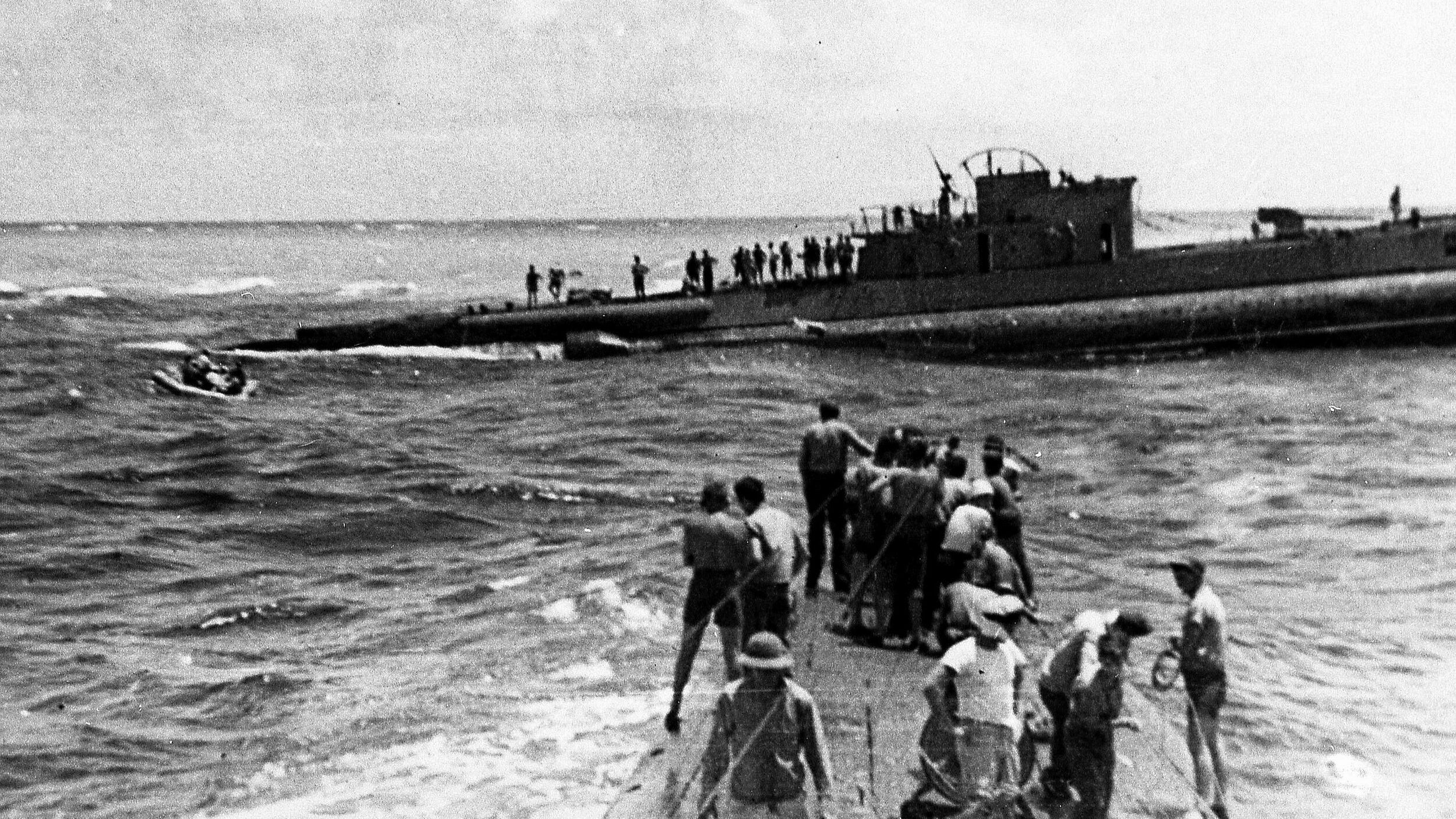

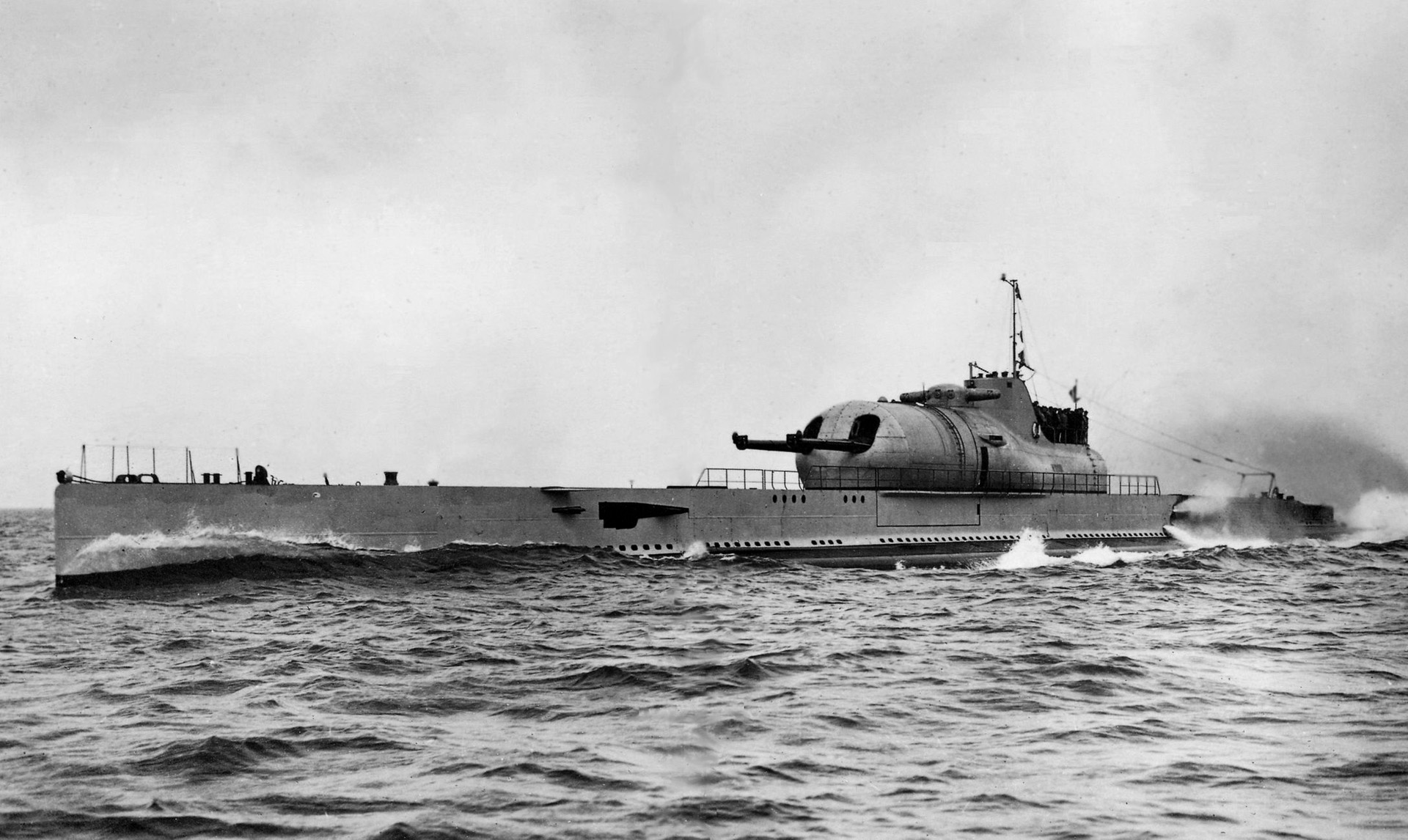

This survivor was among nine Ar-234s surrendered to British forces at Sola Airfield near Stavanger, Norway, after operating with KG 76. A technical team led by U.S. Colonel Harold Watson and known as Watson’s Whizzers collected this and other German high-tech aircraft to be shipped to the United States for flight testing. The aircraft was flown from Sola to Cherbourg, France, on June 24, 1945, where it joined 34 other advanced German aircraft shipped back to the United States aboard the British aircraft carrier HMS Reaper.

Reaper departed from Cherbourg on July 20, arriving at Newark, New Jersey, eight days later. Watson’s pilots took two Ar-234s from Reaper to Freeman Field, Indiana, for testing and evaluation. The fate of the second Ar-234 flown to Freeman Field is unknown. A third Ar-234 was taken off Reaper and assembled by the U.S. Navy for testing, but was found to be unflyable and was scrapped.

After receiving new engines, radio, and oxygen equipment, werke number 140312 was transferred to Wright Field, Ohio. Flight testing was completed on October 16, 1946. After a period of time in storage, during the early 1950s the Ar-234 was moved to the Smithsonian’s Paul Garber Restoration Facility at Suitland, Maryland. The Smithsonian began restoration in 1984 and completed it in February 1989.

Some aviation experts believe that the Jumo 004’s technical problems could have been overcome earlier, that other reasons never fully explained were responsible for delays with this aircraft, and that hundreds of Ar-234Bs could have been in service by the time of the fighting in the Ardennes. The Arado jet bomber, they say, could have substantially delayed the Allies’ victory.

Others insist that while the Ar-234 was a technical marvel, the only jet bomber used in World War II, the Allies had the enormous advantage of sheer numbers of men and machines. By this reasoning, the Ar-234, despite its high-tech qualities, could not have delayed the war’s inevitable outcome.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments