By Patrick J. Chaisson

May 3, 1944: The nondescript army bus slowed to make a turn off the Mount Vernon Memorial Parkway just outside suburban Alexandria, Virginia. Following a gravel driveway through some woods, it first stopped at a hidden guard post where armed M.P.s carefully examined everyone’s identification papers. The vehicle then continued on its way, parking at a wire-fenced enclosure far from public view.

A group of men, all clothed in a motley combination of G.I. fatigues and foreign uniform parts, was herded off the windowless bus. Disoriented after their long journey, many of them blinked in the hot sun. “Wo sind wir?” some were heard to remark. “Was ist hier?”

The crew of U-515 had arrived at Fort Hunt. Here they would match wits with an American interrogation team, all of whom were specially trained in the art of extracting sensitive information from enemy prisoners of war (POWs). At stake was the U-boat’s suite of underwater sensors and weaponry; whichever side possessed this technology could also control the Atlantic convoy routes between North America and Europe.

From 1942 to 1946, the U.S. armed forces conducted several intelligence-gathering operations at Fort Hunt, Virginia, a secluded point of land situated along the Potomac River about 11 miles south of Washington, D.C. Soldiers stationed at this ultra-secret facility interrogated top-ranking Axis captives, ran a covert information clearinghouse, and helped Allied prisoners escape capture.

After peace returned, almost the entire camp was torn down. Only recently has Fort Hunt’s role in World War II come to light, while some of what took place there remains classified three-quarters of a century after the last enemy POW departed.

Originally part of George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate, this 136-acre tract became in 1893 a U.S. Army coast artillery site named Fort Henry Hunt. For decades it slumbered in a caretaker status until the Department of Interior took ownership in 1933. Under National Park Service management, Fort Hunt served as a Civilian Conservation Corps camp during the Great Depression.

After Pearl Harbor, the U.S. War Department established two “detailed interrogation centers,” one on each coast. Fort Hunt, the East Coast facility, was to focus on German captives, while Camp Tracy—a former resort hotel at Byron Hot Springs, California—would perform this function for Japanese prisoners out West. To preserve security, both installations were identified only by their local post-office addresses: P.O. Box 1142 for Fort Hunt and P.O. Box 651 for Byron Hot Springs.

The mission of these interrogation centers was to obtain national-level intelligence through the exploitation of selected enemy POWs. Prisoners who demonstrated in-depth knowledge of technical, industrial, political, or other strategic matters deemed important to the Allied war effort would be identified, transported to Fort Hunt or Camp Tracy, and thoroughly questioned before being sent to a more permanent detention camp elsewhere.

On May 15, 1942, the U.S. Army took control of Fort Hunt for “the duration of the war plus one year.” Hundreds of civilian contractors worked around the clock that summer to install fencing, refurbish existing structures, and erect temporary barracks, mess halls, and warehouses. By the end of July, 87 buildings had been rehabilitated or newly raised there at a cost of $217,000.

Significantly, the entire enclosure was bugged. Listening devices planted in every interrogation room, common area, and prison cell allowed American eavesdroppers to record their captives’ most unguarded conversations. “Even the trees had ears,” said one soldier of these sophisticated electronic surveillance systems.

The first prisoners, U-boat crewmen apprehended after their submarines were sunk in U.S. waters, arrived in August 1942. Under an interservice agreement, the Office of Naval Intelligence routinely interrogated German sailors sent to Fort Hunt. All other captives, however, fell under the control of a shadowy organization known as MIS-Y.

Earlier in 1942, the U.S. Army’s General Staff formed an operational agency it called the Military Intelligence Service (MIS). As MIS’s mandate included the collection of high-priority information from captured enemy personnel, it created a sub-section named MIS-Y to question those POWs.

MIS-Y’s organizational structure closely followed that of MI19, the British Military Intelligence Directorate’s prisoner-exploitation bureau. Several specialized departments—including the Air, Army, and Scientific Research subsections—focused on interrogation, while functional branches such as monitoring, evaluation, and document collection provided operational support.

Finding men qualified to carry out this unorthodox mission presented an enormous challenge. It quickly became evident that successful strategic interrogators required a combination of intelligence, education, language proficiency, and an instinct for the job. Fortunately, Army officials had established a sort of “breeding-ground” for MIS-Y at the Military Intelligence Training Center in Camp Ritchie, Maryland. There, German-speaking G.I.s were already learning the basics of POW interrogation.

Camp Ritchie’s curriculum focused on tactical applications, though, and not the national-level information that MIS desired. Yet many “Ritchie Boys” who demonstrated an above-average knowledge of technical or scientific subjects were recruited for duty at Fort Hunt.

Several Jewish refugees, born in Germany or Austria and forced to leave their homeland after the Nazis rose to power, served with MIS-Y. Although U.S. soldiers, they were officially classified as “enemy aliens” and thus forbidden to question prisoners. The Army solved this problem by transporting these men to a nearby federal courthouse where a judge granted them U.S. citizenship.

Wilhelm Hess, a German-born Jew, had just completed the tactical interrogator’s course at Camp Ritchie when he saw his name posted on a bulletin board. Hess read that he “had been promoted to corporal and was shipping out the next day.” His destination was a mysterious duty station known only as P.O. Box 1142, Alexandria, Va.

Not everyone came from Camp Ritchie, however. John Gunther Dean was training to become a combat engineer at nearby Fort Belvoir when an officer there gave him a nickel and a telephone number to call. Dean was then dropped off in downtown Alexandria, where he found a pay phone.

“I called the number, and I said, ‘Private Dean reporting, sir,’” he recollected. A voice instructed him to wait until someone picked him up. “So I took my duffel bag and I stood there at the corner, and sure enough, [a] staff car came—I felt very important—and I went to Fort Hunt.”

All incoming personnel had to sign a document directing them never to discuss what went on at P.O. Box 1142. Next, each man received his duty assignment.

Some became interrogation officers (I/Os). Corporal Fred Michel said he received very little training in his new job, recalling, “We immediately started interrogations, first with the assistance or supervision of an officer who was already stationed there and who had gone through the experience.”

Corporal Werner Moritz remembered it differently, though. He came to Fort Hunt in July 1942 with the initial cadre of soldiers and recalled six or eight British intelligence officers there who taught him how to question captives. Moritz later said this instruction “was of great value to me” as an I/O.

Other servicemen worked in a cramped concrete building located outside the main POW compound. This was the monitoring station, where German-speaking analysts recorded and transcribed interrogation sessions. They also listened in on the what the prisoners were saying to one another while confined to their cells or out in the exercise yard.

Private First Class George Weidinger, a Vienna-born Jewish immigrant, performed this duty. “I worked as a monitor,” he recalled, “and I remember being in a very, very small room. The small room had a recording device, and I think I spent a good many hours per day there.”

Enlisted men did most of the interrogating and all of the monitoring at Fort Hunt. Fred Michel believed this was because he and his fellow European-born soldiers exhibited superior language skills, adding that the officers assigned to MIS-Y were kept busy performing administrative or supervisory duties.

Most prisoners processed through the Joint Interrogation Center came from one of three sources: the combat theater of operations, POW camps in the U.S., or the port of debarkation. Tactical intelligence teams often identified captives who appeared to have significant strategic value right on the battlefield; other prisoners were earmarked for special interrogation as they stepped off the ship transporting them to the United States. In rare cases, certain POWs were flown directly from Europe to National Airport in Washington, D.C.

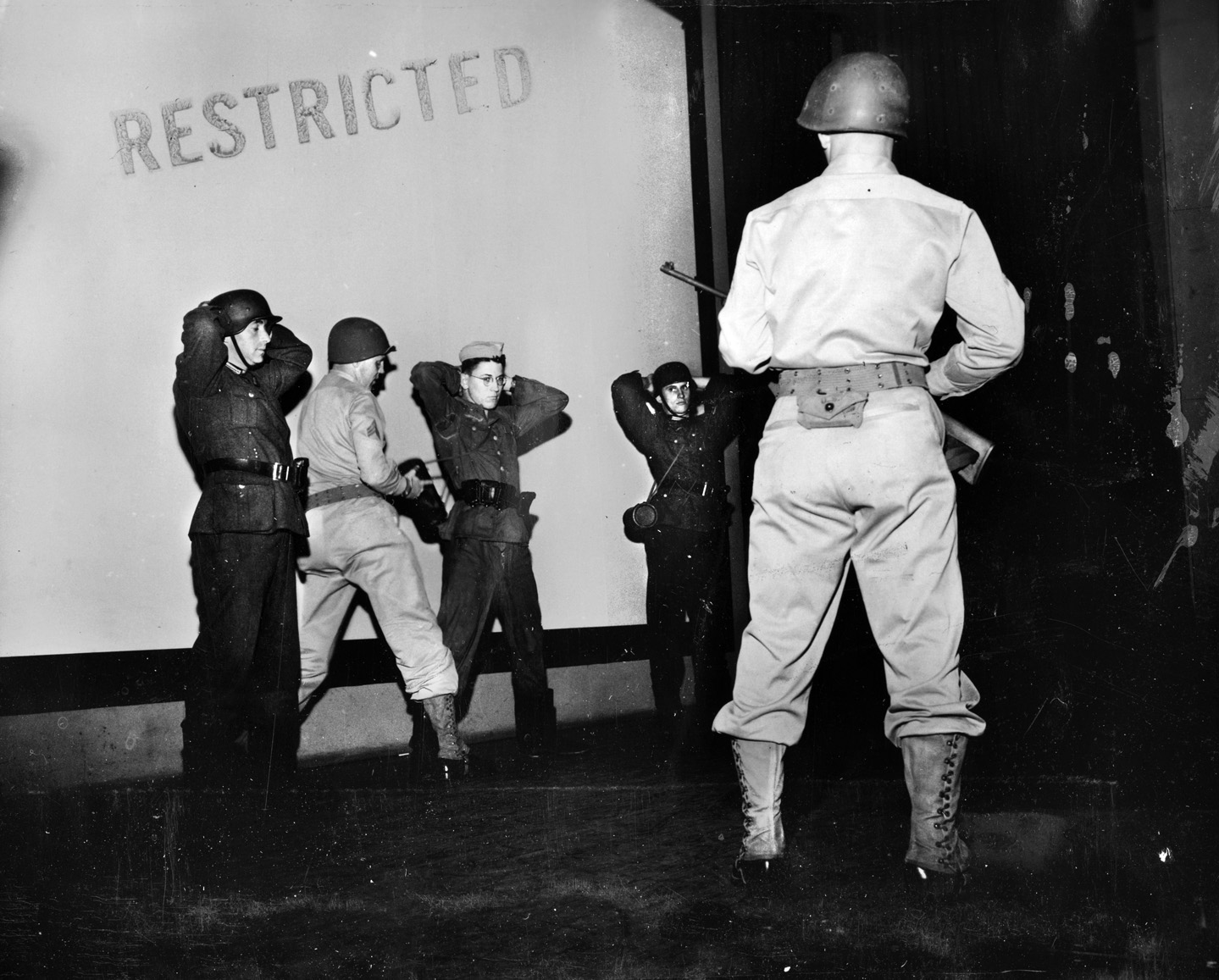

Prisoners arriving at Fort Hunt underwent a formal in-processing ritual known as “intake.” One by one, the POWs were taken into a reception room, interviewed, and told to surrender all personal property. Captives then received a medical examination and a shower, as well as an issue of clothing, toiletries, and personal items. A typical stay there varied but usually did not exceed two weeks.

Inmates ate in their cells, which were typically left locked. They could, however, leave for bathroom breaks and daily recreation time—all under M.P. guard. Normally, within six hours of arrival POWs were escorted down the hall for their first meeting with an American interrogator.

Every I/O was allowed to develop “his own method of handling the various situations which may confront him,” according to an MIS-Y report. This memo further noted, “Each prisoner, being a different individual, requires different treatment.”

Interrogators typically used a mix of flattery and veiled threats to establish a relationship with their often-reluctant subjects. Cooperative inmates earned privileges such as better food and an occasional cigarette. Those who resisted or were caught telling lies, however, received a visit from “The Russian.” This intimidating individual—dressed to look like a member of the Red Army—was in fact an American NCO, but there was no mistaking his message: answer our questions or be sent to the Soviet Union.

The I/Os employed other deceptions, as well. Fred Michel said that when talking with captives he “would wear officer’s insignia. Usually [it was] the rank of the interrogee or maybe one step below that because the feeling was that Germans respected rank, and if somebody of a non-commissioned rank would interrogate them, they wouldn’t expect any results.”

Yet these young intelligence officers largely abided by the Geneva Convention’s rules regarding treatment of POWs. “During the many interrogations,” swore Pfc. George Frankel, “I never laid hands on anyone. We extracted information in a battle of the wits. I’m proud to say I never compromised my humanity.”

Some inmates remained at Fort Hunt long after they were “milked” of all valuable information. Several interrogators recall utilizing German “stool pigeons” to inform on other captives. Slovakian-born Franz Gajdosch, an SS tank commander, briefly performed this function before he got a job tending bar in the base officers’ club.

Electronic surveillance occasionally proved worthwhile, but not always. Staff Sergeant Rudy Pins estimated that “probably only 20 percent of all of the conversation” he monitored was considered useful. Characterizing the prisoners’ chatter, Pins said, “They talk[ed] about their girlfriends, and their sergeants, or whatever. Their families. Nothing of any particular intelligence interest.”

The watermelon-sized listening devices used at Fort Hunt were frequently hidden in overhead light fixtures. Werner Moritz remembered one occasion when he heard a POW tell his cellmate, “I’m getting a funny echo here. I think we’re being recorded.” Moritz described what happened next. “So they took the lights apart. There was a microphone. It was a very, very embarrassing situation.”

A total of 3,415 enemy captives passed through Fort Hunt’s Joint Interrogation Center. Camp records indicate only one escape attempt, but it was a memorable one. As a way of getting him to talk, interrogators told Kapitänleutnant Werner Henke, U-515’s skipper, that he was being turned over to British authorities as a suspected war criminal. On June 15, 1944—his last night there—Henke was shot and killed while attempting to climb the prison enclosure’s perimeter fence.

During the war, MIS-Y contributed to many Allied intelligence successes. Chief among these was the identification of Nazi Germany’s military rocket research facility at Peenemünde months before deadly V2 ballistic missiles began raining down on London. Fort Hunt’s I/Os also got their subjects to talk about such naval technology as acoustic homing torpedoes and the “Schnorchel” underwater ventilation apparatus.

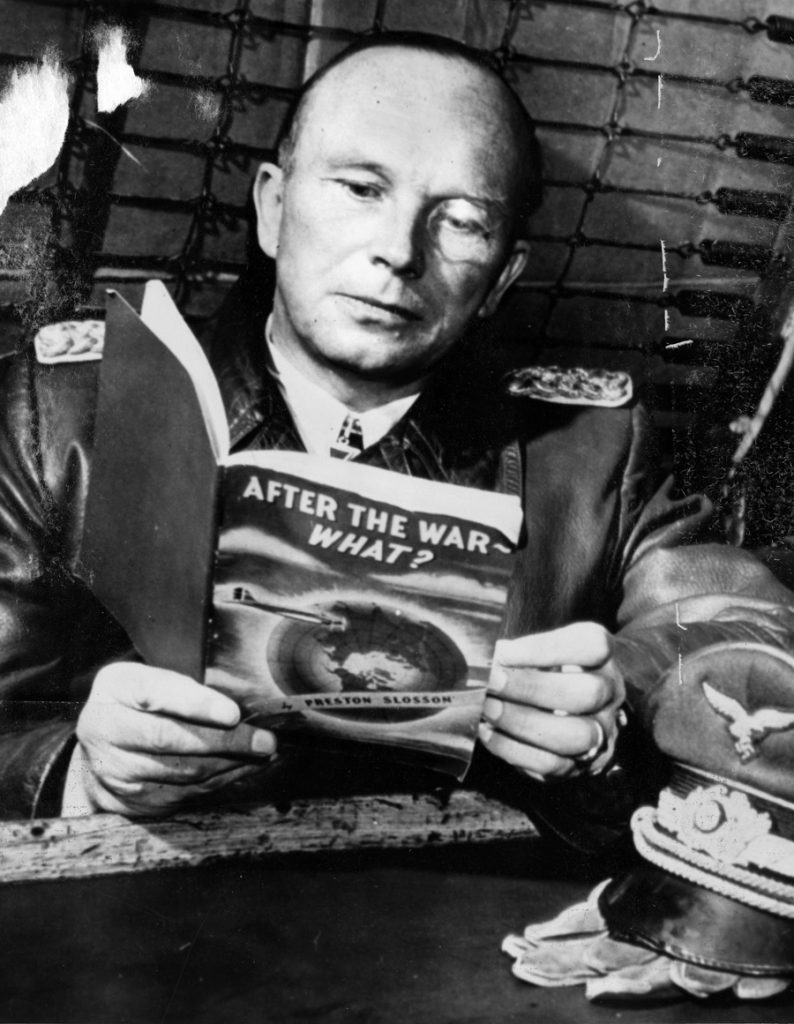

In fact, a U-boat figured in MIS-Y’s last major wartime operation. In May 1945, Germany’s submarine fleet at sea received radio instructions to cease combat operations and surrender. U-234, a giant Type XB cargo sub en route to Japan, capitulated to U.S. destroyers on May 14. Five days later, U-234 docked at Portsmouth Navy Yard in Maine, where it was closely searched by American intelligence officers.

Found on board were technical drawings for the V2 missile, Me-262 jet aircraft, and Hs-293 glide bomb, plus 1,200 pounds of radioactive uranium oxide. U-234’s passengers included a number of top military men and weapons engineers, all of whom would require intensive questioning.

Lieutenant William Hershberger, a document translator with MIS-Y, brought them back to Washington, D.C., on a military transport plane. Accompanying Hershberger on that aircraft were U-234’s commander, Kapitänleutnant Johann-Heinrich Fehler, Luftwaffe General Ulrich Kessler, and an expert in the field of infrared radiation named Dr. Heinz Schlicke.

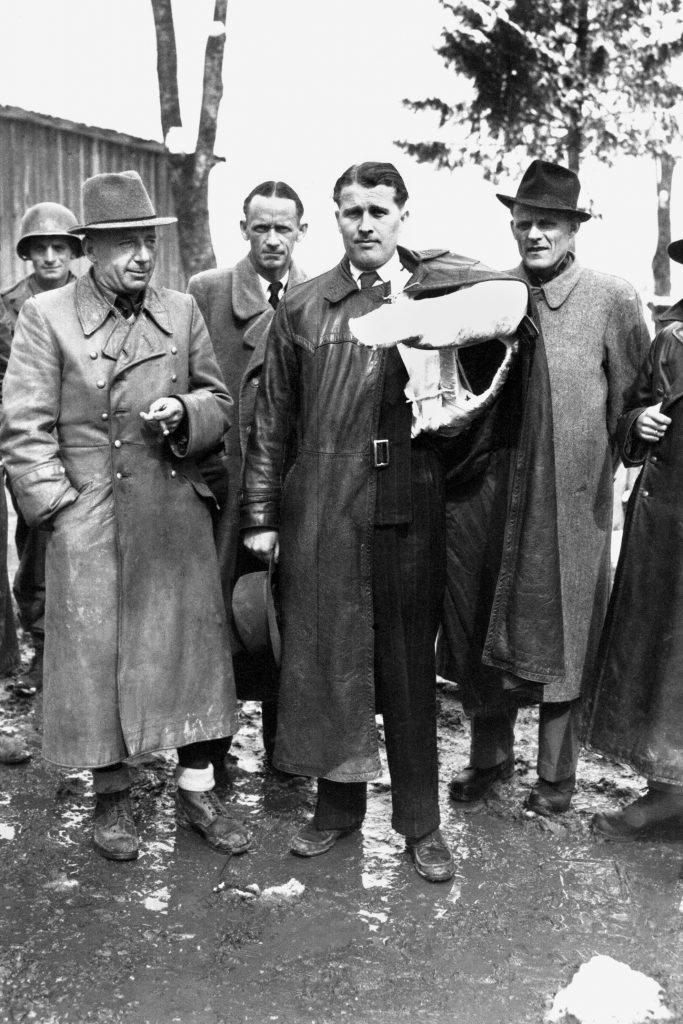

The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff wanted to gain control of people like Schlicke, who headed Nazi Germany’s top military, scientific, and technological research programs. This resulted in Operation Paperclip, a top-secret postwar operation in which 1,600 scientists were brought over from Germany to help develop American weapons systems and to keep their knowledge out of Russian hands.

Fort Hunt served as a processing station for the first Paperclip participants, including noted rocketry expert Dr. Wernher von Braun. Bartender Franz Gajdosch remembered seeing him there in the summer of 1945, as did a 19-year-old morale officer named Pfc. Arno Mayer. Since Germany was no longer an enemy nation, men like von Braun—technically, contractors employed by the U.S. government—enjoyed certain privileges during their stay, such as the occasional shopping trip in town.

The Joint Interrogation Center was not the sole information-gathering activity based at Fort Hunt. Two highly classified organizations also had their headquarters there, kept separate from MIS-Y’s POW enclosures only by a wire fence. These agencies, codenamed MIRS and MIS-X, played a vital role in America’s shadow war against the Axis.

The Military Intelligence Research Section (MIRS) investigated and translated captured enemy documents, newspapers, scientific journals, and other publications. In a temporary building situated across the parade field, teams of German-speaking soldiers painstakingly waded through mountains of printed matter that had been captured by Allied forces.

“We used to get duffel bags full of materials,” said Sergeant Paul Fairbrook, an order-of-battle specialist. “We collected information from various sources, and we put these [pieces of data] on cards. Then we catalogued them.” Fairbrook further recalled how each MIRS analyst had his own particular assignment. “My job was to collect information about German units and what they were like,” he recalled, “and what they had, and what they did, and what their armament was.”

Officers at MIRS sent up the product obtained by Fairbrook and his co-workers for inclusion into an intelligence summary known as the Red Book, so-called for the color of its cover. Updated regularly as the war progressed, the Red Book served as a ready reference on Wehrmacht organization, capabilities, and leadership.

While those soldiers stationed at Fort Hunt knew better than to ask questions, many could not help but wonder what was going on inside the old post hospital. There, another covert operation nicknamed the Escape Factory gave thousands of American servicemen a reason to keep on fighting even though they had been made prisoners of war.

After war broke out in 1939, senior Allied commanders saw a need to exploit their own POWs’ unique knowledge of enemy industrial capacity, morale, and transportation infrastructure. Accordingly, the British War Office formed a bureau within its Military Intelligence Directorate called MI9, not be confused with MI19, which focused on enemy captives. MI9’s chief task was to help servicemen caught behind the lines evade capture and, for those held prisoner, aid their escape and return home.

When, in mid-1942, United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) bombers began flying missions over occupied Europe, some airmen inevitably were shot down. As no American equivalent to MI9 then existed, the Army’s Military Intelligence Service set out to create one. In October 1942 it established at Fort Hunt an Escape and Evasion (E&E) section codenamed MIS-X.

Closely resembling MI9 in terms of organization, this agency contained five subdivisions: interrogation, correspondence, POW locations, training and briefing, and technical. The first three departments kept track of U.S. prisoners, communicated with them, and debriefed those men who managed to successfully escape or evade capture. Training officers provided instruction on E&E tools and techniques, while the Technical Branch developed, manufactured, and shipped a wide variety of cleverly concealed escape aids.

Most personnel worked out of Fort Hunt’s old hospital, which they called “the Creamery.” By December, though, a new structure across the street had been built to house workshops, storerooms, and even a printing press. Named “the Warehouse,” it became Technical Branch’s home.

Instructors began briefing USAAF combat crewmen on ways to avoid capture, as well as the proper conduct expected of them should they be made prisoner. Selected personnel, usually two per squadron, also received training as code users. Those flyers taught to utilize this simple cipher system could secretly communicate by mail with MIS-X or other Allied intelligence agencies.

A cryptographer named Master Sergeant Silvio Bedini ran the correspondence division. He described how letters mailed home from imprisoned code users were intercepted at a New York City post office and forwarded to his desk in the Creamery. Bedini then steamed these envelopes open to read and decrypt their hidden messages before resealing everything and sending the letters on their way.

Posing as friends or family members, workers at Fort Hunt wrote enciphered notes back to the code users. As they were impersonating Americans of various ages and education levels, Bedini’s staff deliberately made errors in grammar and punctuation when penning these communiqués. He said that his “writers had to know how to write badly,” using “poor handwriting, poor language, [and an] inability to express [themselves] properly” so as not to tip off German mail censors.

MIS-X issued thousands of so-called “E&E kits” to U.S. flight crews. While their contents varied depending on the type of unit and operational location, typically these small, waterproof packets held cash or coins, a compass, water purification tablets, high-energy food, and a flexible saw that could cut through metal. Many downed aviators, including Flight Officer Charles E. “Chuck” Yeager, evaded capture thanks to the survival gear they carried.

Technical Branch also supplied a dizzying assortment of escape aids to the 95,000 American servicemen imprisoned by Nazi Germany during World War II. As these objects were sure to be confiscated if discovered, MIS-X staffers worked hard to conceal them from enemy postal inspectors.

Inside the Warehouse, skilled craftsmen modified ordinary comfort items like shaving brushes, ping pong paddles, and cribbage boards to hide a wide variety of smuggled paraphernalia. Their wares included tissue paper maps secreted underneath checkerboard tops and German currency rolled into hollowed-out shoe brushes.

American industry supported this effort, as well. The Scoville Manufacturing Co. of Waterbury, Connecticut, fitted tiny compasses inside some five million G.I. buttons, while Boston’s Gillette Razor Co. made magnetized blades that pointed north when balanced on a string. The U.S. Playing Card Co. even placed map segments within special peel-away cards.

Perhaps MIS-X’s most extraordinary product was its baseball-radio. The F.W. Sickle Electronics Co. of Chicopee, Massachusetts, produced dozens of miniature radio transmitters, which were sewn inside baseballs by Cincinnati’s Goldsmith Baseball Co. Workers at the Warehouse surreptitiously marked these “hot” sporting goods so POWs would recognize them as escape aids.

Technical Branch covered its activities by creating two bogus humanitarian agencies, the War Prisoner’s Benefit Foundation and the Serviceman’s Relief. The staff there prepared plenty of “straight” packages, which contained only unaltered items, in order to minimize suspicion. Parcels containing contraband were considered “loaded.”

Occasionally, MIS-X mailed out boxes stuffed with European-style clothing, photographic equipment, and even small-caliber pistols. No attempt was made to disguise their contents; instead, intelligence officers notified POWs beforehand so they could try and sneak these so-called “super-dupers” past distracted German inspectors.

At one point, workers at the Escape Factory were boxing up 120 packages per week for delivery to U.S. servicemen held in German POW camps. The equipment they sent out helped facilitate over 700 successful escapes. Another 10,000 Americans evaded capture due in part to the E&E kits that MIS-X supplied.

As World War II wound down, so did the top-secret activity at Fort Hunt. In June 1945, MIRS relocated to Camp Ritchie, while on August 20, MIS-X received an order to “burn all your records and artifacts on hand within the next 24 hours.” MIS-Y’s strategic interrogation center closed for good during the summer of 1946.

The National Park Service demolished most of Fort Hunt’s abandoned military structures when it regained control of the property in 1948. Today, Fort Hunt Park has become a popular riverside recreation area along the George Washington Memorial Parkway. Little evidence of its clandestine past remains, except a commemorative marker recently placed near the park’s flagpole.

Dedicated to the veterans of P.O. Box 1142, this plaque describes how their work “not only contributed to the Allied victory, but also resulted in strategic advancements in military intelligence and scientific technology.” It is a fitting memorial to Fort Hunt’s shadow-warriors.

Patrick J. Chaisson is a writer and historian based in Scotia, New York.