By Louis Ciotola

For nearly two and a half centuries, Prussia celebrated June 28 as a birthday of sorts. On that date in 1675, the Prussians achieved the start of their proud military tradition. The state was then known as Brandenburg, ruled by an elector of the Holy Roman Empire, Frederick William. A minor player on a European continent that was still recovering from the cataclysmic Thirty Years’ War, Brandenburg and its elector were about to change history.

Faced by an invading army from Sweden, one of the foremost powers of the day, the Brandenburgers prepared for battle at the little town of Fehrbellin, northwest of Berlin. They were there to decide the future of their state. Victory promised unprecedented growth, while defeat nearly ensured that Brandenburg would remain a minor entity no greater than many others spread out across Germany. On the other side of the lines, the Swedes too were at a crossroads. Their mighty empire was extended beyond what its meager resources could defend, and they fought to maintain a tenuous supremacy in northern Europe. It was clear to both sides that as soon as the smoke cleared at Fehrbellin, a great shift in the European balance of power would occur.

The Sun King, Frederick William and the Young King Charles XI

Without a doubt, France under the great “Sun King,” Louis XIV, was the dominant power in Europe during the third quarter of the 16th century. Following the close of the Thirty Years’ War in 1648, France had emerged as the strongest kingdom on the Continent, making it inevitable that the ambitious Louis would dictate the ebb and flow of European politics for years to come. In ensuing conflicts, states fought either with France or against her. Fighting on the side of Louis XIV provided the luxury of being allied to the most powerful monarch in Europe, yet it also brought the threat of becoming a mere French satellite. In fact, opposing the mighty armies of France courted disaster. However, if victory could somehow be achieved, the prospects of increasing one’s prestige and influence were tremendous. In 1672, when Louis launched a war of conquest against the Dutch Republic, two very different states were forced to make that difficult choice.

The larger of these states, Sweden, already possessed a strong tradition as a French ally. The alliance of Sweden and France had checked the swelling power of the Hapsburgs during the Thirty Years’ War. The resulting Treaty of Westphalia had extended Swedish control over the Baltic, most notably in Germany, where Sweden received a large portion of Pomerania. Sweden’s subsequent military success against its neighbors allowed the Swedish kingdom to expand still further. By 1672, the size of the empire presented the young King Charles XI with a dilemma. Sweden’s acute lack of resources and funds made its recent conquests extremely vulnerable. Only through constant expansion could it manage to protect itself, but with a pacific-minded government in place to watch over the youthful king, conquest was not an option. The Swedes would have to work hard simply to maintain their possessions, especially in Germany, where Pomerania and other territories served as an additional front against would-be aggressors. Given their crippling financial crisis, it was obvious that the Swedes would need outside help if they wished to hold onto all the pieces of their empire.

The other state was on the opposite end of the spectrum. Brandenburg was a poor territory in the northeast corner of the Holy Roman Empire. It had few outside possessions and almost no influence aside from its status as an electorate of the empire. Its current ruler, the elector Frederick William, having come to power during the Thirty Years’ War, had suffered the humiliation of being unable to prevent foreigners from marching through and devastating his lands. He desperately sought to remedy the situation. In his mind, the only solution was to create a formidable military that could compete with the major European powers surrounding him. A few years earlier, in 1667, he had made that point clear to his son, stressing that the only way for a state to become “considerable” was to command a strong army.

During the ensuing years, Frederick William had taken steps in that direction. Following a brief Tartar invasion of his easternmost territory of Prussia, the elector was able to raise the money for a standing peacetime army. This army, extensively drilled and brutally disciplined, was talented enough to catch the eye of many contemporaries in Germany, although it was still far too small to earn the respect of its larger European neighbors. Brandenburg now possessed an officer corps that was tied to the interests of the state rather than functioning merely as a group of mercenaries concerned with their own careers and financial gain.

Something of a novelty in the period, Frederick William always made it a point to consult his officers in times of war. Brandenburg was well on its way to forming an army that eventually would pose a challenge to any opponent. However, it could scarcely reach its goals alone. In 1672, it remained vital for Brandenburg to tie itself into alliances with outside powers that were willing to provide the subsidies necessary for an enlarged military to exist. That year, the opportunity to both acquire such subsidies and test the new army in action fell into Frederick William’s lap.

Leveraging Leopold against Louis XIV

The elector was no friend of France. He saw Louis XIV as a continual looming threat to Germany. When a French army attacked Holland, initiating the Franco-Dutch War, Frederick William was quick to pledge his support to the Dutch Republic. His services, however, came at a price. The wealthy Dutch, needing allies badly, were only too willing to accommodate him, agreeing to pay for half the 20,000-man Brandenburger army. But the prospect of facing the indomitable French war machine alone was daunting. Fortunately for Frederick William, a strong ally in the form of the Austrian Hapsburgs emerged to challenge the French as well. The elector had been working to persuade the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold to join him in combating Louis, and he was delighted when the emperor dispatched an army to the Rhine under Raimondo Montecuccoli, a talented commander and a hero of the Thirty Years’ War.

Unlike the elector, Leopold was intimidated by French arms and had little interest in rescuing the beleaguered Dutch. The emperor wished only to protect Germany, and in accordance with this wish he ordered Montecuccoli to act conservatively and engage the enemy only if victory could be assured. He even secretly informed Louis that he would keep the Austrian army behind the Rhine. Although he was well aware of Leopold’s stance, Frederick William was confident that he could convince Montecuccoli to take action. Besides, he had little choice but to combine with the Austrians if he wanted any chance to fight—attempting to battle the French alone would be nothing short of suicide.

Frederick William expected the Dutch to hold out for a considerable length of time, but when the republic was almost entirely absorbed by France during the course of one lightning-fast campaign, the need to act decisively became ever more pressing. The elector begged his Austrian ally to advance against Henri Turenne, the great French general leading the enemy forces in Westphalia, but Montecuccoli refused to budge. His frustration mounting, Frederick William attempted to push the Austrians into the war, convincing them that he, being an elector of the Empire, was in overall command. He managed to lead the army into Westphalia, but Turenne was unwilling to do battle and beat a hasty retreat. Shortly afterward, Montecuccoli regained control of his own army and terminated the brief offensive. Sitting idle, the allied army consequently suffered terribly from a lack of provisions.

Contrary to appearances, Montecuccoli was highly upset by his orders. He, like Frederick William, preferred to attack, but the emperor had tied his hands. Finally, the old veteran could take his dishonorable role no longer and left the field. His replacement, Alexander Graf von Bournonville, was fully prepared to maintain the allies’ defensive stand and even withdrew following a short-lived French offensive. Frederick William was livid. He wrote to Leopold in exasperation: “I fear the French will follow us and my lands be totally ruined and my fortresses lost, and I will have to conclude a humiliating peace.” It was no idle threat. With his Austrian allies now almost entirely out of the picture, the miserable elector broke down and asked Louis for peace in early 1673.

Despite nonexistent Austrian support and dwindling Dutch subsidies, it was still a difficult decision to make. Frederick William was overwhelmed with dismay. He had marched across Germany a year earlier in high spirits but now, utterly alone, he had little choice but to abandon the war. Louis, by contrast, was overjoyed to see one of his enemies accepting French supremacy, and he quickly agreed to the elector’s offer of peace. The two sides subsequently forged the Peace of Vossem, in which Louis asked nothing of Brandenburg and even pledged to provide the electorate with subsidies, an obvious attempt to keep it from considering a re-entry into the conflict.

Breaking the Peace of Vossem

Although he had escaped a potentially deadly situation relatively unharmed, Frederick William could not shake off the feeling of disgrace he experienced by having to sign the Peace of Vossem. Within months of the treaty, he was searching for an excuse to break it. Already the French were failing to deliver the promised subsidies, and when Montecuccoli returned to retake control of the Austrian army and actually went onto the offensive, the elector decided to resume his war with France. Louis, in turn, invaded Germany proper and became an even greater menace.

A developing threat to his back door by Sweden did nothing to diminish Frederick William’s enthusiasm for war. Since 1672, Louis had been paying the Swedes to maintain an army of 16,000 men in Pomerania for the sole purpose of intimidating Brandenburg, but Frederick William felt he had little to worry about from them. For the time being, he was correct in this assumption. Fearful of risking its fragile hold on its territories along the north German coast, Sweden had no interest in going to war with Brandenburg. In fact, Swedish envoys had eagerly helped negotiate the terms of the Peace of Vossem. Just to be certain, however, Frederick William forged a nonaggression pact with the Swedes before plunging again into war with France.

“To Teach Kings the Respect They Ought to Have”

Despite the new pact, the elector’s position was still perilous. There was no guarantee that the Austrians and the Dutch would welcome his return. The Austrians were unsure of the elector’s intentions and feared that Brandenburg would again abandon the cause, while the Dutch had little reason to believe that a new offensive was worthy of their funds. In the end, it was a risk the Dutch had to take, and they agreed to once again partially subsidize Brandenburg’s army. On July 1, 1674, Frederick William officially rejoined the coalition against France, marching back toward the Rhine with 16,000 men. The elector entered the war for the second time as enthusiastically as he had the first, proudly declaring that he had arrived “to teach kings the respect they ought to have for electors of the Empire.” As it turned out, the elector was once again overly optimistic. Operating independently for the first couple of months, the Brandenburgers were too weak to strike Turenne. By the time they agreed to reunite with the Austrians in October, Montecuccoli had retired for the second time in as many years, only to be again replaced by the lethargic Bournonville.

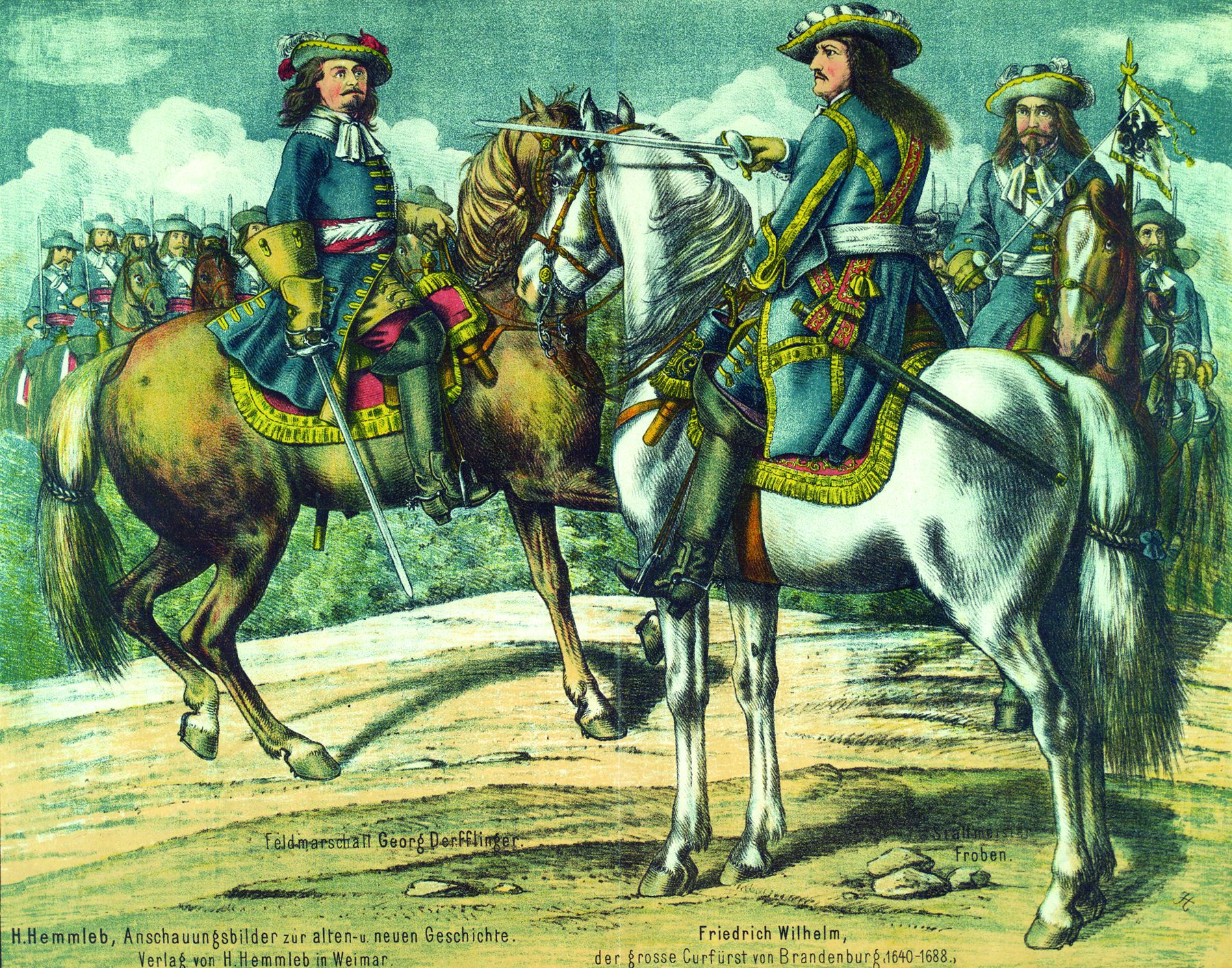

As in his previous campaign, Bournonville, despite being numerically superior to Turenne, refused to take the offensive. Even when the chance arose to win a decisive victory at Marlenheim, the Austrian commander dallied. Frederick William, along with his most trusted general, the Austrian Georg von Derfflinger, begged Bournonville to take action, but to no avail. Instead, the emperor’s chosen general claimed that his troops were exhausted, an utterly preposterous assertion given the complete inertia of the army during the preceding weeks. Incensed, the Brandenburgers took it upon themselves to assault Turenne independently, but without the support of their allies, they could achieve nothing.

Much the same transpired in October near Strasbourg, where the Brandenburgers attacked the French but again came up short when the Austrians failed to support the assault. This time it cost the life of Frederick William’s own son, Carl Emil. The largest disaster, however, occurred that winter at Turkheim, where Turenne launched a surprise attack against an allied force now suffering acutely from food and supply shortages caused directly by its idleness. Although the Brandenburgers put up a valiant resistance, Bournonville’s decision to withdraw the following day rather than renew the battle spoiled the stunning achievement of the elector’s men. Compounding matters, the Austrians consistently blamed the campaign’s dismal outcome directly on Frederick William. Settling into winter quarters at the end of 1674, the spirits of the Brandenburgers and their ruler were all but crushed. It would take nothing short of a miracle to revive them.

Sweden Breaks the Nonaggression Treaty

That miracle was about to occur. Two years earlier, Sweden’s chancellor, Magnus de la Gardie, had pushed the empire into an alliance with France. He had argued convincingly that Sweden was in desperate need of cash and that if it failed to declare itself with France and make a grab for funds, then its hated rival, Denmark, would do so in its place. At the same time, the young and impressionable King Charles XI had just reached the age of legitimacy and was assuming power from a regency government. Unwilling to sacrifice anything to the despised Danes, Charles accepted the advice of his chancellor, yet limited the extent of Swedish involvement to the preservation of a strong garrison in Pomerania. No one in Sweden wished to take any unnecessary risks. By the second half of 1674, however, a combination of logistical difficulties and French pressure made an undesired war with Brandenburg increasingly likely.

Louis was indeed growing impatient with his northern ally, suspecting the Swedes of being content to selfishly drain his coffers without lifting a finger to come to his aid. The French monarch had heard the stories of Brandenburger grit at Turkheim and doubted that the elector would willingly exit the war a second time. Louis consequently pressed the Swedes to invade Brandenburg in order to draw Frederick William away from the Rhine.

Despite being a lover of war, Charles XI was not eager to comply with the French demand. Unfortunately for the young king, reality on the ground called his hand. Given the grave condition of his overextended realm, more French subsidies were imperative. The situation was especially dire in Germany, where the cost of supplying the garrisoned Swedish army in Pomerania had become too much to bear. It soon became apparent that the army, to survive, must advance into Brandenburg and begin taking its necessities by force. After procrastinating for as long as possible, Charles at last issued the order to take the offensive. It was Christmas Day, 1674.

A renowned hero of the Thirty Years’ War, Karl Gustav Wrangel led the 20,000 men of the Swedish army from Pomerania into Brandenburg. The Swedes gave hardly a thought to their violation of the nonaggression treaty with Brandenburg, considering it a military necessity. The timing for the war was ideal. Frederick William had stretched his resources to the limit in order to campaign against France, and Brandenburg was virtually defenseless. Only the elector’s brother-in-law, John George, prince of Anhalt-Dessau, remained to contend with the surprise Swedish invasion. There was nothing he could do aside from humbly requesting that Wrangel turn back. Naturally, neither Wrangel nor his younger brother Waldemar, who at times controlled the army because of the elder’s recurring case of gout, even considered meeting the request. Instead, without any serious opposition, the Swedes fanned out across Brandenburg to pillage the countryside and replenish their army.

The ensuing devastation reached right to the gates of Berlin itself. Slowly, the Swedish army made its way toward the Elbe. Frederick William was encamped with his army deep inside Franconia when news of the Swedish invasion reached him in early January. He had previously assumed that Sweden would refrain from any such move because of the divisions within its government and the strength of the Dutch fleet. He was wrong. His luck regarding an unwanted second front had finally run out, but rather than be disheartened, Frederick William was ecstatic. On hearing what had occurred, the elector exulted, “I can use this to get all of Pomerania.”

The Swedish incursion gave him an excellent excuse to leave behind his worthless allies along the Rhine and win martial glory for himself. That winter, however, the army was ill-prepared to march. Furthermore, certain diplomatic measures were required before it could confidently engage the Swedes—namely, negotiations with the Dutch Republic concerning naval assistance against the Swedish fleet. Delaying the process even more was a sudden attack of the gout that prevented Frederick William from reaching The Hague until May. Luckily for him, the Swedes were in no mood to press their advantage.

The Capture of Rathenow

When the elector finally petitioned the Dutch for aid, they agreed to dispatch their fleet to the Baltic to challenge the Swedes. A request for support to the Austrians, however, proved pointless. As expected, the Holy Roman Emperor was unwilling to sacrifice any of his army in the defense of Brandenburg. Nevertheless, the overall results were satisfactory, and on June 5 the Brandenburgers set off to meet the Swedish threat. Frederick William traveled with the infantry, while the experienced Derfflinger assumed overall command. The army marched in three sections: the left under Prince Friedrich II of Hesse-Homburg, the right led by General Joachim Ernst von Gortzke, and the center directed by Derfflinger.

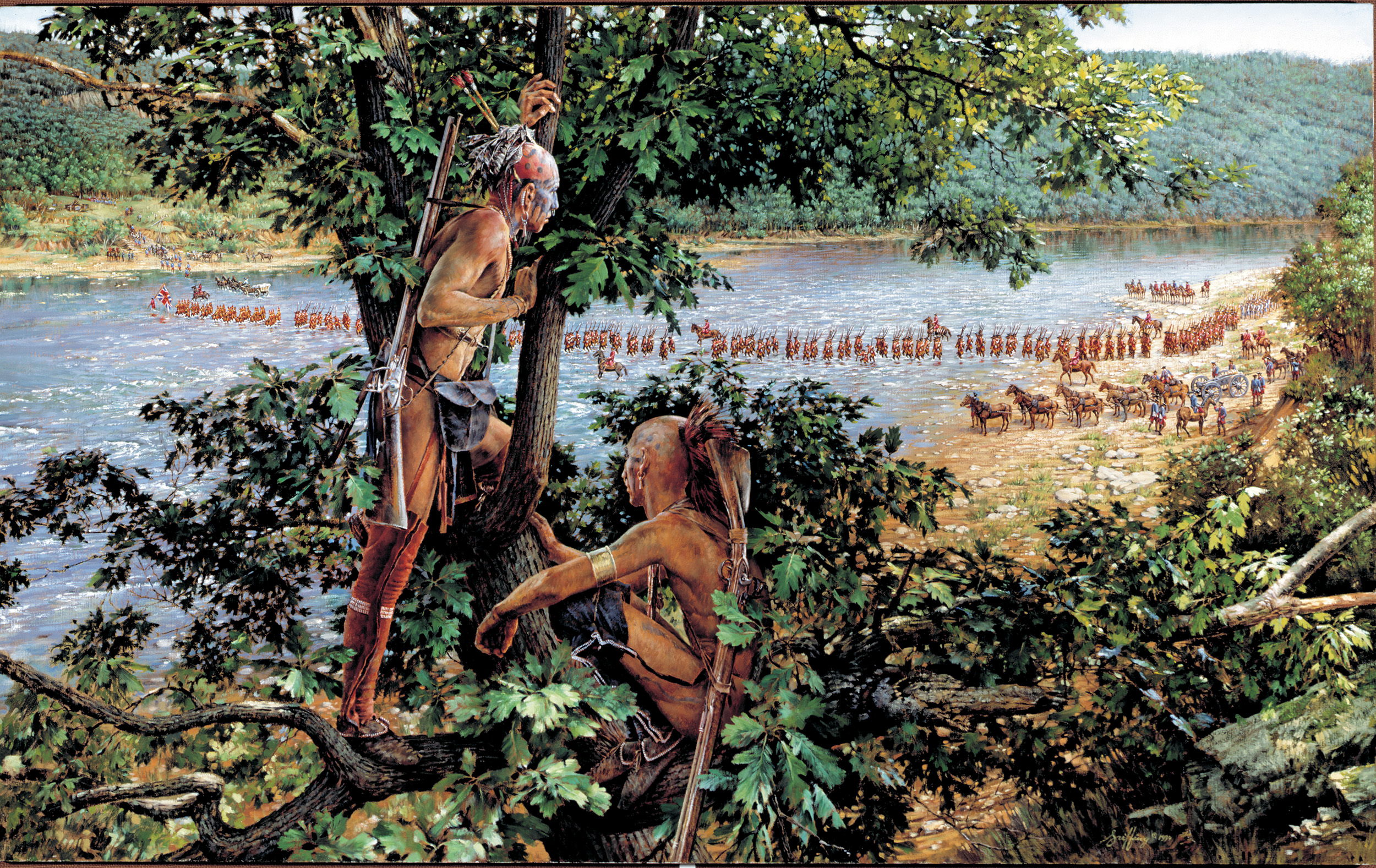

The march was a stunning success. Despite having to traverse the formidable Thuringian Forest, which was still relatively barren of supplies after the devastation of the Thirty Years’ War, the Brandenburgers moved rapidly, covering nearly 200 miles in 20 days. It was a remarkable display of troop coordination, and the Brandenburger generals conducted the move so secretly that upon reaching their destination, they were as yet entirely undetected by the Swedes. The local peasants along the road, however, were well aware of their ruler’s return, and they celebrated proudly with banners that read: “We are only peasants, and little land we have; but we give our blood for our lord cheerfully.”

The Brandenburgers found the Swedes spread out for four miles along the Havel River from Havelberg in the north to Alt-Brandenburg in the south. The elder Wrangel commanded in the north, while Waldemar led the Swedish troops in Alt-Brandenburg. To the Swedish rear lay a conglomeration of large swamps—a certain detriment should a sudden, hurried retreat be necessary. According to Branderburger spies, the Swedes had no idea that the elector’s army had drawn so close. Oblivious to the circumstances, the Swedish army concentrated solely on garrison duties and the brutal business of suppressing the numerous peasant uprisings in the area.

Frederick William was fully determined to use Swedish ignorance to his advantage. He concocted a strategy in which he would quickly capture the little town of Rathenow, located directly between Havelberg and Alt-Brandenburg, and split the Swedish army in two. Knowing that success relied entirely upon the element of surprise, he prepared to move with great speed and accordingly decided to advance with only his cavalry and as many infantry as could be loaded onto available wagons. The strike force amounted to 6,000 cavalry and 1,200 foot. The remainder of the army would follow and catch up when it could.

The Brandenburgers departed for Rathenow on June 25. Trudging through the mud created by a blinding rainstorm, they reached the town’s gates at midnight. By pretending to lead a Swedish column, Derfflinger succeeded in tricking the sentries into opening the gates, after which the Brandenburgers poured through. With great fury the attackers swarmed inside the town, catching the vast majority of the Swedes asleep in their beds. Completely confused, the defenders were either killed or captured, and the town soon fell. The entire operation cost Frederick William a mere 15 men.

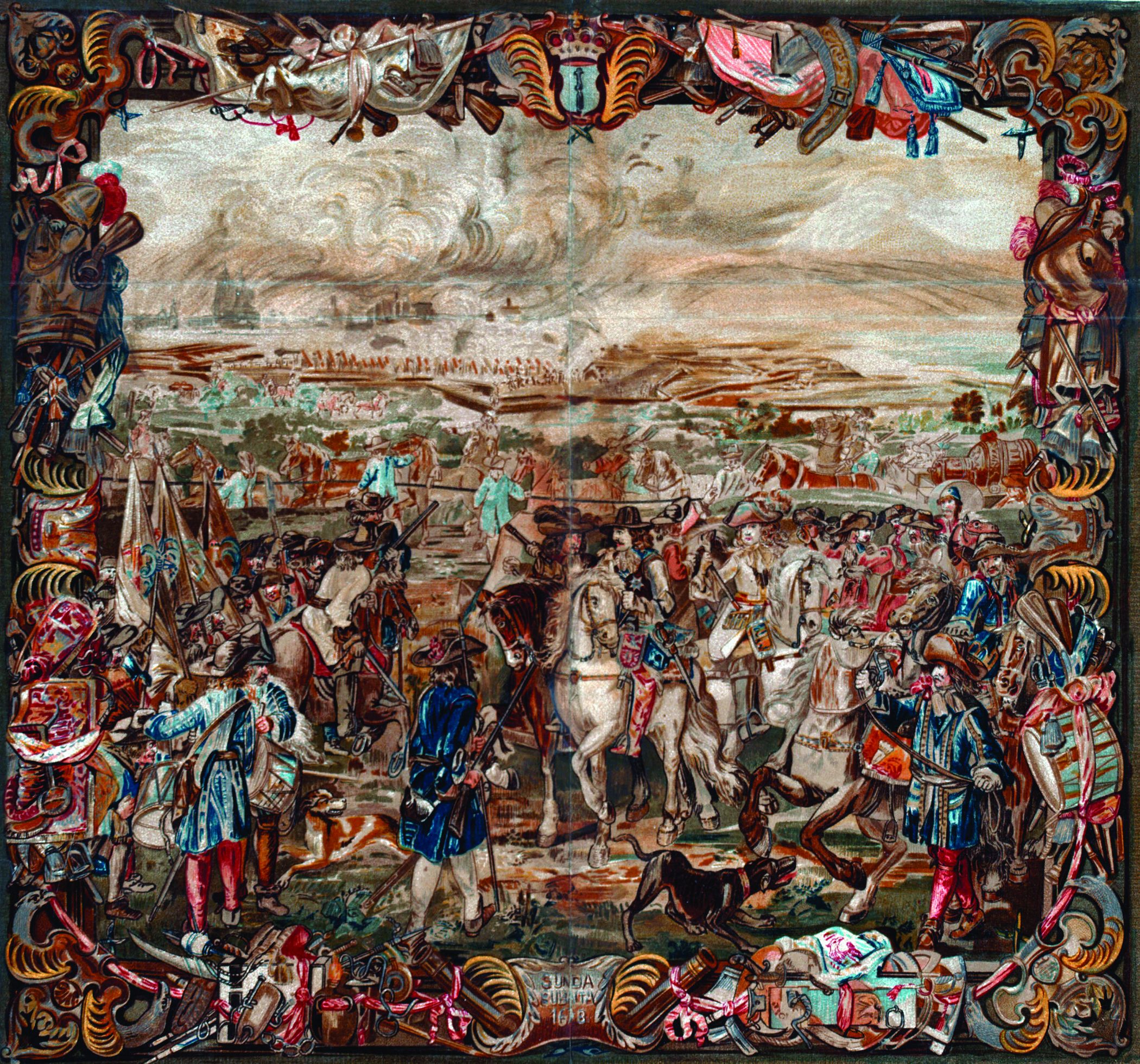

The Battle of Fehrbellin

Upon hearing of the unexpected attack, the Wrangel brothers, shocked by the surprise, incorrectly estimated the number of Rathenow’s assailants. Judging the attacking Brandenburgers to be much greater in strength than they actually were, the Wrangels decided against counterattacking Rathenow and opted to withdraw. This was exactly what Frederick William had expected; he was already ordering his victorious cavalry forward to cut off the Swedish retreat. Derfflinger opposed the strategy, arguing that his horsemen were too exhausted from the march and the assault on Rathenow, but the elector, backed by Prince Friedrich, overruled him, stressing the need for a decisive campaign.

A loyal soldier, Derfflinger dropped his objection and set out at once. His target was Waldemar’s contingent, which had left Alt-Brandenburg and was heading east for the small town of Fehrbellin, on the Rhine, where the Swedes planned to reunite their forces. Aware that Fehrbellin was the only suitable place to cross the marshes, Derfflinger knew exactly which route the younger Wrangel would take. The Brandenburger cavalry raced forward, hoping to cut off Waldemar at Nauen, but the enemy proved too slippery and had already passed by. It would be up to another group of Brandenburgers, speeding toward Fehrbellin itself, to block the Swedish escape.

Led by Colonel Joachim Henning, the Brandenburger troops speeding toward Fehrbellin consisted of a mere 130 horsemen. Their purpose was to avoid the enemy, beat them to the town, and destroy the town’s lone bridge, thus severing the Swedish retreat. Upon reaching its destination, the raiding party immediately set the bridge afire, but the destruction had barely commenced when the Swedes began arriving early on June 28. Waldemar found the bridge smoldering yet still very much intact. It needed only minor repairs before it could be crossed. Frederick William had no intention of providing the time necessary to do so, declaring confidently, “We are so close to the enemy, that he must lose his hair or his feathers.”

Waldemar knew that the main Brandenburger army was close, but he did not fear an attack. He correctly surmised that the only way Frederick William could possibly reach him before the bridge was repaired was with cavalry alone, and he believed such an attack without infantry support would be far too risky. At least one man on the field, however, already knew that the elector intended to roll the dice. That man was Henning, who, along with his tiny band of soldiers, was already hiding inside Fehrbellin, hoping to delay the Swedes as long as possible.

The wait was brief. Shortly after Waldemar’s arrival, the advance elements of the Brandenburger cavalry under Prince Friedrich arrived on the scene. Frederick William, still en route, ordered the prince to await his arrival, but the prince was impatient and, determining the Swedes to be on their last legs, ordered an immediate attack through the pouring rain. Initially, Friedrich’s cavalry was successful in pushing the defenders back, but the Swedes fought back tenaciously and quickly brought the offensive to a halt.

An Uphill Charge

Frederick William, Derfflinger, and the rest of the Brandenburger cavalry arrived at noon, raising the elector’s total strength to roughly 7,000 horsemen against the equally numerous Swedes. Unlike Frederick William, Waldemar also possessed infantry and thus was at a decided advantage. Inexplicably, the Swedish commander did a curious thing. Rather than exploit his victory with an immediate counterattack, he ordered his troops to stay put. He was dead set on retreating across the bridge, no matter what. Waldemar soon realized his error when the rest of the Brandenburger cavalry reached the field and rapidly occupied the hills opposite the Swedish right. This put Waldemar’s entire army in danger of being outflanked. Waldemar had no choice but to attack—only now he would be forced to make an exposed uphill charge.

Frederick William positioned his 13 light field guns atop the hill in preparation for an enemy counterattack. The Swedes’ own 38 cannons, only seven of which were operational, would be unable to assist in the assault. Furthermore, the Swedish left, hindered by the marshes, would be unable to add any additional weight to the attack. Already the Brandenburger artillery was raining hell down upon the Swedes, goading the younger Wrangel to move. The elector’s men would not be disappointed. On Waldemar’s command, a wave of Swedish infantry, followed by cavalry, stormed up the hill. Despite the cannon fire searing through their ranks, the Swedes charged madly, putting the battle’s outcome in doubt. They reached the hill’s summit and captured the Brandenburger artillery. It appeared that the gambling elector was about to be routed.

But Frederick William had no intention of meekly accepting defeat. Rallying his men, he raced to the front of the line, crying: “Forward! Your prince and captain will conquer with you, or die like a knight!” In his zeal, the elector suddenly found himself surrounded by enemy soldiers. His master of stables, Emanuel Froben, was struck down, supposedly on account of his riding Frederick William’s gray horse (an exchange in mounts having been made to help ensure the elector’s safety). The situation was dire, but to Frederick William’s great fortune, a band of nine dragoons pierced the enemy ranks and extracted him from harm. Meanwhile, the elector’s bravery had inspired his men, and the Brandenburgers began to drive back the Swedes. They recaptured their guns, which to everyone’s amazement had not been spiked, and poured furiously down the opposite slope of the hill. With their cannons blazing, the Brandenburger cavalry smashed into the remnants of the disordered Swedish right and sent it fleeing into Fehrbellin.

The Brandenburger officers, their blood up, urged Frederick William to light the town, but he rebuked them, stating, “I am not come to destroy my country, but to save it.” Instead, the elector ordered his horsemen to storm the Swedish infantry. The ensuing attack failed, and the desperate Swedish soldiers held firm. Frederick William called off further offensives and was content to allow the remaining Swedes to withdraw. Waldemar, satisfied to cross the now-repaired bridge, subsequently did so in good order, leaving behind eight of his cannons. Exhausted by days of hard riding and fighting, the Brandenburgers declined to pursue.

Triumph for Brandenburg

The Brandenburger victory at Fehrbellin came at the cost of only 500 men. Swedish casualties were much higher, and they would lose still more as a result of incessant peasant raids. At the close of the campaign, Waldemar had a paltry 4,000 men remaining at his disposal. Nevertheless, both sides claimed victory. Frederick William celebrated his driving off the Swedes, while Waldemar insisted that his bloody charges had delayed the enemy long enough to save the bulk of his force. Psychologically, however, the triumph belonged to Brandenburg, which earned the distinction of being the first minor German state in modern times to deal such a stunning blow to a major European power.

Upon hearing the news of Fehrbellin, the people of Berlin immediately began referring to their ruler as the “Great Elector,” making it clear that they expected Frederick William to continue accomplishing great things. In the years following the battle, he did just that. During the final months of 1675, the Brandenburger army drove the Swedes into Mecklenburg, where Charles XI’s tormented army withered still further. Initially, a lack of allies forced the Brandenburgers to halt, but 1676 brought a renewal of fortune. Although Emperor Leopold continued to deny him any assistance, Denmark joined the elector in an alliance that would soon take the war into Sweden itself. Shortly afterward, a combined Dutch-Danish fleet intercepted the Swedish navy and wrecked nearly three-quarters of it. Without a strong maritime presence in the Baltic, Sweden’s army in Germany was cut off, giving Frederick William a decided advantage.

The elector utilized his opportunity to the fullest. During the subsequent campaign he successfully conquered Swedish Pomerania, capturing Stettin, Stralsund, and Greifswald in succession. Then, during the winter of 1678-1679, Frederick William equaled the brilliance of the Fehrbellin campaign when he marched his army across the frozen lagoons at Frisches Haff and Kurisches Haff to outflank the Swedes and force them to retreat from Prussia altogether.

Limited Gains

Unfortunately for Brandenburg, its gains would not reflect its military success. Although it had made a profound statement, Brandenburg remained a minor continental player, still subject to the whims of the larger powers. By 1678, the Dutch were trying to push Frederick William into making peace out of fear of the elector’s growing strength. Later that year they abandoned him altogether, forging with France the Treaty of Nymwegen. The Austrians signed for peace soon after. Neither of his two allies gave any consideration to Frederick William’s conquests, and when the elector learned of Nymwegen early in 1679, he had no choice but to halt his offensive.

Incensed by the betrayal, he vowed to fight the French alone, but when Louis dispatched an army toward Brandenburg, Frederick William conceded. On June 29, he reluctantly signed the Treaty of St. Germain, effectively wiping out all of his gains by restoring the conquered territories to Sweden. So angered was he by the Dutch Republic and Austria that he would consent to being an ally of hated France for the next six years.

Although stiffed at the peace negotiations, Brandenburg had made tremendous gains, establishing an army and a military tradition far greater than any of their German counterparts. After Fehrbellin, the Great Elector earned the leverage necessary to enlarge his peacetime army against the wishes of the noble estates. This made it much easier for Brandenburg, and later Prussia, to mobilize its military upon the outbreak of hostilities, giving it the ability to immediately compete with its neighbors. The seeds were thus sown for the dramatic growth of the army in generations to come. At the same time, the battle served to underscore Sweden’s gradual decline. Although it would again prove itself a force to be reckoned with under its next king, Charles XII, the Swedish empire, stretched thin and exposed as little more than a client state of France, was doomed to inevitable collapse. The daring horsemen of Frederick William had seen to that at Fehrbellin.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments