By Robert F. Dorr

In the darkness and driving rain on August 29, 1918, German artillery shells smashed down on American artillerymen fighting on a fir-clad slope in the Vosges Mountains in Alsace. The rumor spread that this was a gas attack. The Americans, who should have been preparing to fire back, were confused and scared, donning gas masks and affixing equine gas respirators on the snouts of their horses. Some men panicked, turned, and ran amid the piercing roar of the barrage. Several horses, including those towing two artillery guns, ran off in the wrong direction.

The captain in command was up on his horse, trying to direct his soldiers in the chaos, darkness, and rain. A German shell ripped into the wet earth 15 feet from him. His horse collapsed and fell into a gaping shell hole, landing on top of the captain and pinning him down. After a soldier rushed over to help, the officer scrambled to his feet, gasping and shaking, just in time to see more of his men turning and running. In the black night, confusion everywhere, the officer stood tall, held his ground, and let loose with a stream of profanity. It was rough language his men had never before heard from the slim, bespectacled figure who was usually stiff and reserved.

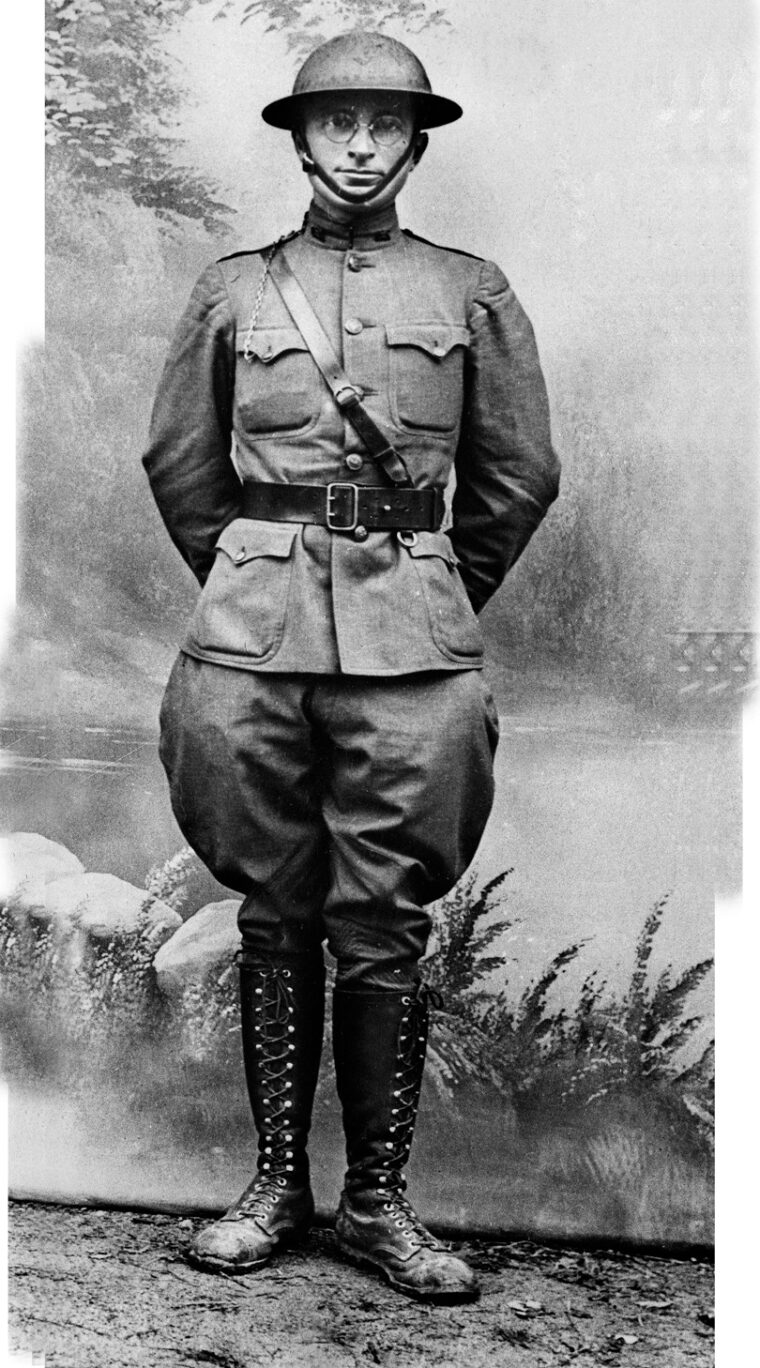

Thus began World War I for Captain Harry S. Truman, a Missouri National Guardsman newly in charge of Battery D, 129th Field Artillery, 35th Division. Truman inherited an unruly, insubordinate band of men who had scared away a previous commander. They seemed incapable of working together.

Their first fight on that hilltop in the Vosges was not so much a failure as a fiasco, but it also was the last time Truman’s battery performed poorly. At 34, Truman was more mature than the officers who had preceded him. He wielded a brand of leadership that combined stern guidance with a genuinely friendly nature. Creating a word play on the Civil War’s First Battle of Bull Run, his men soon called the action in the Vosges the “Battle of Who Ran.” Instead of sapping their morale, the event galvanized them. It filled them with a resolve never to turn and run again; it gave them an experience they would share for the rest of their lives. But their greatest test in combat was yet to come.

Just after the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt on April 12, 1945, his successor, Truman, delivered a radio address to the U.S. Armed Forces. He referred to the commander in chief’s having fallen —many Americans had never known any president but Roosevelt—and then drew upon his experience to add:

“As a veteran of the First World War, I have seen death on the battlefield. When I fought in France with the 35th Division, I saw good officers and men fall and be replaced…. I know the strain, the mud, the misery [and] the utter weariness of the soldier in the field. And I know too his courage, his stamina, his faith in his comrades, his country and himself.”

Truman was born in Missouri in 1884, had an unremarkable upbringing at a farm near Independence, and was prevented from attending a military service academy by his poor vision. Accounts differ on whether Truman applied and was rejected or simply never applied.

In the Army’s Field Artillery Journal, Lt. Col. James B. Agnew described how George R. Collins of Kansas City, on his own volition early in the 20th century, organized a field artillery battalion as part of the local National Guard:

Collins “recruited, in addition to about 60 other ‘fine fellows who worked in banks and stores around town [Agnew wrote],’ the bespectacled Truman, then 21 years of age.” The year was 1905. “Truman found himself in the lofty station of private soldier serving on a 3-inch gun, then the Army’s standard field piece.”

According to his memoir, Truman enjoyed Guard meetings and serving with men “who would pay a quarter for the privilege of drilling once a week.” He learned the basics of artillery work as a member of Battery B, 2nd Missouri Field Artillery, a component of the Kansas City unit, during summer encampments at Camp Girardeau, Missouri. Among other skills, Truman learned to handle the spirited six-horse teams used to draw field guns and caissons. This was the kind of experience that would serve Truman well years later when the world’s great powers went to war on July 28, 1914, and the United States joined in on April 6, 1917.

Truman left the National Guard in 1911. He worked at a succession of jobs. He donned the uniform again when the United States entered the Great War.

In keeping with custom in National Guard units, the men of Truman’s mixed Kansas-Missouri outfit elected their leaders. Truman was always patting his pockets to confirm that he had extra pairs of eyeglasses with him, for he lived in fear of being unable to see. This prompted one of his fellow soldiers to dub him a worry wart. Still, Truman was both liked and respected. Not everyone believed his claim of surprise when the men elected him a lieutenant.

Already mature compared to his fellow artillerymen, Truman was toughened and made more mature when his unit—the 129th Field Artillery Regiment of the 60th Field Artillery Brigade, a component of the 35th Infantry Division—trained in 1917 at Camp Doniphan at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Fellow artilleryman Nathan Serenko called Truman “a quiet dynamo.” Fellow soldier and future political henchman Harry Vaughan called him “one tough son-of-a-bitch of a man…. And that,” was part of the secret of understanding him.”

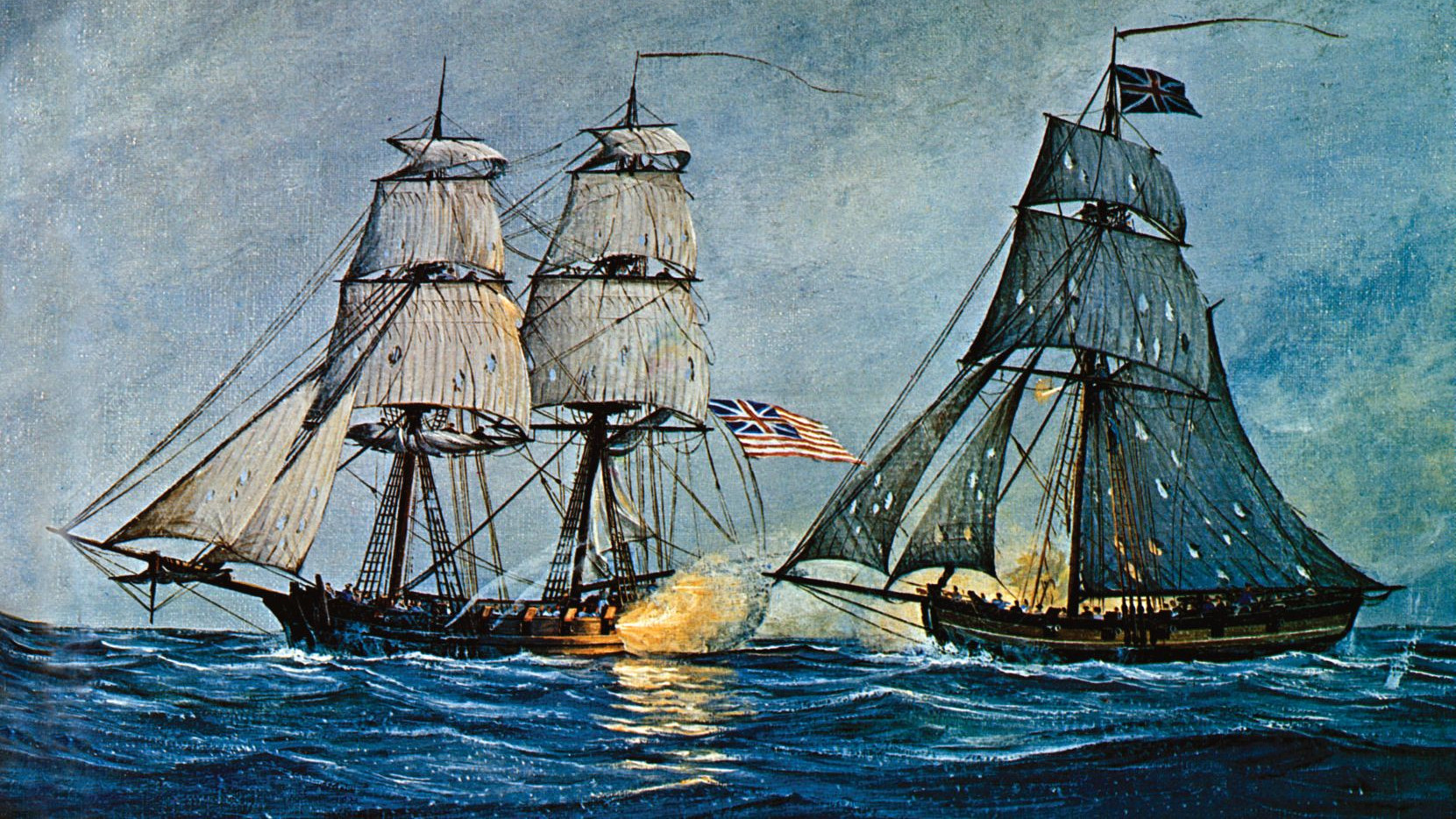

After Fort Sill came France. According to a letter written to his future wife, Bess, First Lieutenant Harry Truman landed in Europe as a member of the Allied Expeditionary Force on April 14, 1918. Having debarked from the 36,000-ton Army transport ship George Washington after the journey from New York, Truman spent his first day overseas at the Hotel des Voyageurs in the French port city of Brest. He had gotten to France ahead of the bulk of the 35th Division and had time for artillery training in France, where he was introduced to the famous French 75mm artillery guns.

It was quite a contrast to the plain 3-inch gun Truman had used stateside—a relic of the era just after the American Civil War. Truman’s regiment had six artillery batteries, each with four of the weapons officially dubbed the French 75mm Field Gun, Model 1897. The gun used an innovative recoil system consisting of two hydraulic cylinders, a floating piston, a connected piston, a head of gas, and a reservoir of oil. Troops said it never jammed and could be relied on for accuracy and smooth operation.

Once his men joined him and completed further training, Truman was designated commander of Battery D in his battalion of the 129th and promoted to captain without yet having received the paperwork or the pay. That meant the slight Missouri officer was in charge of 200 men, four French 75mm guns, 24 horses, and associated caissons and battery equipment.

Following their baptism of fire in the Vosges, which had been a sleepy backwater before the Americans arrived, Truman and his entire division were given a difficult order by the Allied Supreme Command. They were to move from one end of the battle line to the other in dreadful weather in what artillery historian Agnew called “one of the most prodigious and exhausting road marches ever devised in modern warfare.”

Uprooted from the low level of hostilities in Alsace, the division and much of the Army’s I Corps were pointed north in driving rain on primitive roads east of Verdun. The men, horses, and field pieces slogged north, often within three to five miles of the front and thus within range of far-reaching 105mm German artillery. They encamped by day and moved by night, hoping to foil German aerial observers.

The long march by Truman and so many others—long disparaged by regular Army soldiers as mere Guardsmen who could not hack it—provided a brutal taste of war under conditions where each soldier must have felt helpless to influence his fate. A typical artilleryman in Truman’s battery lugged 60 to 70 pounds of gear while each horse was burdened with extra harness, forage, a grooming kit, and an equine gas mask.

Truman had plenty of time to think during this ordeal and was undoubtedly focused on what lay ahead. He had to know that his battery’s tactical mobility and fighting prowess was being eroded as the march claimed the one thing the artillerymen needed most: the horses. Throughout the 35th Division artillery, including Truman’s unit, artillery commander Brig. Gen. Lucien Berry later said that roughly 20 percent of the horses succumbed to the terrible conditions of their abrupt and lengthy movement.

Truman must have wondered if his soldiers realized, by that point, that he possessed the technical skills to lead them and the horsemanship needed in an army utterly dependent on animal power for transportation. Did they feel themselves under good leadership each time they pulled the lanyard to send a round flying toward the foe?

They did. The evidence is overwhelming on that point. Despite whatever doubts he may have had, Truman was blessed with plenty of self-confidence. He also knew that his bookish appearance was a factor he had to overcome as a leader and that, despite being under fire in Alsace, his battery had not yet proven itself. But Truman also knew he and his men could meet the challenge.

The troops and their surviving animals reached the heights above the Aira River, and the 35th Division prepared to launch its first offensive of the war at daybreak on September 26, 1918. The dull thumping sound of German 105mm artillery guns increased in tempo as Truman’s artillerymen stacked ammo, set up gun positions, and began firing in support of the attacking 35th Division infantrymen. It may have been the noisiest moment of the Meuse-Argonne offensive, but it was also a moment characterized by competence. The chaos exhibited by Truman’s battery back in Alsace was replaced with busy, businesslike efficiency.

“Truman was not a large man and not imposing, but he could be very strict,” wrote artilleryman Serenko, in a memoir prepared by a family member. “He did not hesitate to discipline soldiers who failed to measure up, even when they were senior noncommissioned officers. He was stern but you could see that he genuinely cared, so most of the men liked him.”

“Captain Truman watched with satisfaction while his four guns, rolling and thundering, fired 3,000 rounds during the 4-hour preparation and rolling barrage,” added Agnew. “The violent fire program was designed to afford the infantry a running start against the expectant Germans, who were dug in [and] determined, yet already disillusioned by the Allied victories at St. Mihiel and Belleau Wood.”

Over the next four days, the 35th Division gained ground, lost ground, and regained lost ground. A busy and businesslike Truman moved his artillery forward even as the infantry was sustaining heavy casualties. Truman was constantly in motion between his command post and forward observation sites as the great offensive unfolded. One of his artillerymen claimed that the guns were in such constant use that men draped water-soaked blankets over smoldering tubes. Each time soldiers opened a breech to reload, it was like opening the door of a hot oven.

During the constant movement, still pummeled by the almost continuous rainfall, Truman’s battery was at times in the right place to fire upon the foe but the wrong place relative to friendly infantry. Because of poor communication, driving rain that sometimes arrived horizontally like incoming bullets, and the difficulty of traversing a battlefield riddled with shell craters, Truman’s battery at one point actually positioned itself some 200 yards in front of the infantry it was supposed to support.

To get into the fight, the artillerymen had to pull their horse-drawn guns through an area they had bombarded earlier. One of Truman’s soldiers later wrote of riding “over the destruction that had been wrought by our guns. It looked like humans, dirt, rock, trees and steel had been turned up by one plow.”

On September 30, 1918, the casualty-ridden 35th Division was pulled off the line but its artillery element stayed in place, providing support, then, for the 1st Infantry Division, the “Big Red One.” The Allies were continuing the Meuse-Argonne offensive, in which 26,000 men would lose their lives. By the time they, too, were pulled back on October 3, Truman and the other artillerymen had won a letter of praise from 1st Division commander Maj. Gen. Charles L. Summerall, the Boxer Rebellion veteran and future chief of staff who was considered the U.S. Army’s foremost artilleryman. The stigma of coming from the National Guard was beginning to dissipate.

Ordered back into battle in mid-October, the 35th Division went to Verdun, the scene of one of the bloodiest among the earlier battles of the war. Truman’s men set up their guns on heights overlooking the Woevre Plain with the Meuse Valley at their backs.

By then, the 129th and Truman’s Battery D no longer had any need to prove anything. They exchanged fire and counterfire with Germany batteries. Truman’s battery was credited with either wiping out or forcing the abandonment of two opposing artillery batteries and also clearing out a German observation post—but at the same time, their ranks bristled with rumor. The buzz was that the belligerent nations in the awful war were close to agreeing to an armistice.

It was a war Truman had never needed to be in. In 1911, he had mothballed his uniforms. He was a farmer and grew food for the war effort. He was the sole supporter of his mother and sister. His vision was below military standards. He was 33, two years older than the age limit set by the Selective Service Act. Any of these factors were legitimate grounds to be exempted from service.

Before sunrise on Monday, November 11, 1918, Truman received a field phone call from Major Newell T. Paterson, his regiment’s operations officer. Paterson had been instructed to tell Truman that a cease-fire would take effect that day. Truman’s Battery D already had fired 68 rounds in the general direction of the German lines. Paterson urged Truman not to tell others about the instruction for fear it might turn out to be a mistake. But soon afterward Truman received the same order that went to everyone in his battalion. There was to be no artillery fire after 11 am.

“I fired the Battery on orders until 10:45 when I fired my last shot on a little village—Hermaville—northeast of Verdun,” Truman wrote in his memoir. Several batteries within the battalion claimed to fire the last round of the war before the 11th-hour armistice, one of them supposedly at 10:59 am, but Truman’s made no such claim. Truman also wrote: “We stopped firing all along the line at eleven o’clock. It was so quiet it made your head ache.”

Twenty-seven years later, when he was elected president of the United States, Truman became the first combat veteran to take the office since the beginning of modern warfare.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments