By Marc D. Bernstein

By mid-April 1951, the war in Korea was nearly 10 months old. United Nations forces had suffered a reversal of fortunes in late 1950 with the entry of Communist China into the war, losing the South Korean capital of Seoul but later regaining it. Now the U.S. Eighth Army, a multinational force that was dominated by American leadership and troops, found itself engaged in limited offensive operations near the 38th Parallel in the wake of General Douglas MacArthur’s removal by President Harry Truman as U.N. Supreme Commander and U.S. commander in chief in the Far East. The new supreme commander, based in Tokyo, was General Matthew B. Ridgway, who had led Eighth Army out of the dark period following its collapse the previous December. Lt. Gen. James A. Van Fleet was named the new commander of the Eighth Army and took charge on April 14. Facing the UN forces in Korea were some 700,000 Communist troops, with an additional 750,000 available in Manchuria. Against this, Van Fleet fielded 230,000 men on the front line and 190,000 more in reserve.

Holding Seoul

Ridgway’s strategy was to eschew taking or holding of ground for its own sake in favor of killing as many enemy troops as possible. Korea was evolving into a war of attrition, and the Truman administration wanted a negotiated settlement. Maoist strategy disapproved of attritional warfare, promoting instead the concept of annihilation. Ridgway and Van Fleet both knew the Chinese were preparing a major offensive designed to drive Eighth Army completely off the Korean Peninsula. No negotiations would be possible until the Communists were convinced through a decisive battlefield defeat that annihilating U.N. forces in Korea was no longer a realistic possibility.

A massive attack by the Chinese Communist Forces (CCF) and North Korean People’s Army (NKPA) was in fact long overdue. Their offensive had been delayed a number of weeks because, in part, of a secret CIA operation that intercepted a much-needed shipment of medical supplies and personnel bound for a Communist-held port. Supply in general had become a major problem for the Communist armies in Korea, as the weight of the UN aerial interdiction campaign was making itself felt. Meanwhile, the Eighth Army had stockpiled critical supplies, especially ammunition and fuel, in anticipation of the enemy offensive.

Ridgway and Van Fleet differed over the value of retaining Seoul in the face of an onrushing enemy force. Ridgway believed that the capital had no real military value and that the major stand, if necessary, should be made south of the natural barrier of the Han River. But Van Fleet thought that holding Seoul had immense psychological and political implications. To lose the city once again to the Communists would be unacceptable, if it could possibly be prevented. Van Fleet eventually was able to convince Ridgway. During the enemy offensive, an all-out effort would be made to save the capital.

The Spring Offensive

The Chinese were anxious to launch their attack. The commander in Korea, Marshal Peng Dehuai, wanted to act before U.N. forces could attempt a major amphibious landing behind Communist lines in North Korea. On April 14, Mao approved Peng’s plan for what became known as the Fifth Phase Offensive. Peng’s specific goal was to destroy five U.N. divisions and recapture Seoul as a May Day present for Stalin and Mao. Mao himself was looking for a clear-cut victory. After weeks of being on the strategic defensive, he wrote: “It is necessary for the contestants to have a decisive engagement. And only a decisive engagement can settle the question as to who wins and who is defeated.” The spring offensive would prove to be decisive, but not in the way that Mao intended.

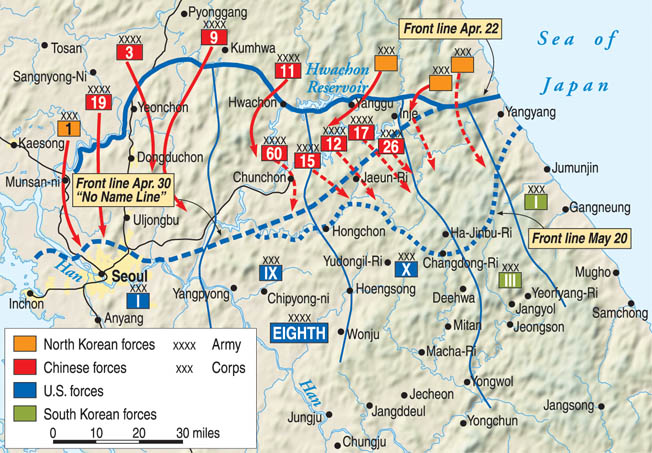

On April 22, the Eighth Army was still attacking toward the main Chinese logistical center of the Iron Triangle in central Korea above the 38th Parallel. I Corps was on the left, with positions anchored along the Imjin River north of Seoul and farther east to the north of Line Kansas. Also north of Line Kansas were the two divisions of IX Corps, which occupied positions to the right of I Corps at the western edge of the Hwachon Reservoir. East of IX Corps was X Corps, which was arrayed near Line Kansas. Still farther to the east were two Republic of Korea (ROK) corps operating slightly above Line Kansas and extending all the way to the Sea of Japan north of the coastal town of Yangyang. There were six American divisions on the front line.

Signs of an impending enemy attack were mounting by the late afternoon of the 22nd. Aerial reconnaissance spotted large numbers of Chinese troops moving southward toward the advancing Eighth Army. Interrogation of prisoners had yielded information that a major offensive was imminent. In order to conceal their movements and hinder UN air attacks, the Communists had set fire to a large amount of scrub near the front line and were also using smoke generators to establish a gray haze over the battlefield. As late as the evening of April 21, the Eighth Army’s G-2 (intelligence officer), Lt. Col. James C. Tarkenton, still had been unsure of the nearness of the enemy offensive, but by 1900 hours on the 22nd, the U.S. 24th Infantry Division commander, Maj. Gen. Blackshear M. Bryan, was certain enough that he notified I Corps headquarters that he expected to be attacked at 2100 that night. “I think this what we have been waiting for,” he stated. His prediction proved generally accurate, but the ROK 6th Division in the IX Corps sector to Bryan’s right was the first to be hit by the Chinese assault. The Communists had chosen a night with a full moon to launch their new offensive.

A Disgraceful Rout

The weight of the onslaught fell on the western half of the Eighth Army front, against I and IX Corps. Auxiliary attacks were made on the flanks of the main assault and also east of the Hwachon Reservoir. The ROK 6th Division cracked immediately. From positions north of Route 3A, the South Koreans fled in panic south, east, and west, exposing the right flank of the 24th Division and the left flank of the U.S. 1st Marine Division and leaving several supporting artillery units uncovered against infantry attack. IX Corps commander Maj. Gen. William M. Hoge, in an after-battle report to Ridgway, stated: “The rout and dissolution of the [ROK] regiments was entirely uncalled for and disgraceful in all aspects. The fact that all units in the division from squads to regiments withdrew in disorganized confusion without offering resistance, and that weapons and equipment were abandoned to the enemy, indicated a lack of leadership and control of all grades of officers and noncommissioned officers.”

The 6th Division’s collapse meant that other units in the vicinity would have to move quickly to prevent the Chinese from infiltrating deep behind their lines. Maj. Gen. Oliver P. Smith, commanding the 1st Marine Division, immediately ordered forward a battalion of the 1st Marines to tie in with the 92nd Armored Field Artillery Battalion and shore up the Marines’ left flank. The Communist 120th Division failed to penetrate the Marine positions west of Hwachon, but Hoge nevertheless ordered the Marines to pull back to the Pukhan River and establish a new line anchored near the Hwachon Dam and swinging southwest to link up with the ROK 6th Division on Line Kansas. The ROK troops were reorganizing some three miles south of Line Kansas but failed to move into position as ordered by Hoge. As a stopgap measure, in mid-afternoon of the 23rd, Hoge ordered the 27th Commonwealth Brigade to block the Kapyong River Valley behind the ROK troops to prevent the Chinese from moving unimpeded down the valley and cutting Route 17 at Kapyong town. Brig. Gen. B.A. Burke’s forces occupied hills on both sides of the river, four miles north of the town.

The block was established by the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment on the right, and the 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry on the left. These troops were supported by several U.S. units, including Company A, 72nd Tank Battalion. By 2200 hours on April 23, the ROKs in front of the 27th Commonwealth Brigade had disintegrated and the Chinese 118th Division was in contact with the Australians. During the night and the following day, bitter fighting took place on Hill 504, with the Chinese losing heavily but continuing to press the attack against the Australians, who were well supported by artillery and the U.S. tanks. By late afternoon of the 24th, the Australians were ordered to withdraw, taking up new positions near brigade headquarters at Chongchon-ni. The Canadian battalion on Hill 677 west of the river was attacked heavily on both flanks shortly after midnight on April 24-25. The U.S. tankers came to the Canadians’ assistance early on the 25th, and by 1630 on that day the enemy had withdrawn. The 27th Commonwealth Brigade had successfully prevented a breakthrough in the critical Kapyong sector, allowing the 24th Division time to pull back to better defensive positions.

“They Came on in Wave After Wave”

Meanwhile, on the 23rd, Van Fleet ordered a withdrawal across I and IX Corps’ fronts to Line Kansas. The Chinese were using more artillery than usual while relying on mortars and automatic weapons to support human-wave infantry attacks. They were attempting a double-envelopment of Seoul from the north and northeast. A few miles east of Kapyong, the 92nd Armored Field Artillery Battalion (a self-propelled 155mm howitzer outfit) established an infantry perimeter and fought off attacking Communist infantry by firing its howitzers at point-blank range. The 92nd’s commander “saw fragments of Chinese soldiers thrown twenty feet or higher into the air.”

Second Lieutenant Joseph Reisler of the 1st Marines described another Chinese attack: “They came on in wave after wave, hundreds of them. They were singing, humming, and chanting, ‘Awake, Marine.’ In the first rush they knocked out both our machine guns and wounded about ten men, putting a big hole in our fire—and those grenades, hundreds of grenades. There was nothing to do but withdraw to a better position, which I did. We pulled back about fifty yards and set up a new line. All this was in the pitch-black night with Chinese cymbals crashing, horns blowing, and their god-awful yells.”

Sergeant First Class Woody Woodruff of the 35th Infantry, 25th Division, recalled the withdrawal of his unit: “Shortly commenced a nightmare that continued almost until daylight. In our column were infantry on foot, tanks, and attached half-tracks mounting Quad-fifties from the A/A battalion. Units got mixed up and mingled. Vehicles with dead engines, some as a result of enemy action, blocked the narrow trail. At one point a column of vehicles from Battalion trains had been ambushed and set afire; flames lit up a night otherwise pitch dark, and ruined what little night vision we had. Among those vehicles were some ambulances; it was reported that some patients aboard had been machine gunned as they lay on their stretchers.”

The Delaying Action of the British Gloucesters

With limited exceptions, Eighth Army’s withdrawal was well executed. On the I Corps left, at the Imjin River north of Seoul, the British 29th Brigade, which was attached to the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division, fought a classic delaying action against the Chinese 63rd Army. A Belgian battalion, caught north of the Imjin, was extricated with the help of the U.S. 7th Infantry, but the 1st Battalion of the Gloucester Regiment was surrounded. The Gloucesters occupied a position astride Route 5Y, which fed into Route 33, leading directly to Seoul. The pullback of the ROK 1st Division on the Gloucesters’ left had exposed their flank. Lt. Col. James P. Carne, commanding the battalion, ordered his unit to withdraw to better positions on Hill 235, south of Choksong. There, the Gloucesters made their stand. Throughout the day, 25-pounders from the 45th Field Regiment of Royal Artillery supported the hard-pressed infantry, and the U.S. Air Force operated continuously against enemy avenues of approach. These measures relieved the immediate pressure; but still the Chinese infantry continued to press forward.

Several attempts were made by units of the 3rd Division to break through to the Gloucesters, but they were halfhearted and unsuccessful. By the morning of April 25, the Gloucesters were finally given permission to attempt a breakout from Hill 235. Only 39 troops in the battalion got back to friendly lines; most of the rest were captured. But the Gloucesters had fought a magnificent fight for 60 critical hours, for which they would receive a Presidential Unit Citation and Carne a Victoria Cross.

Van Fleet called the Gloucesters’ battle the “most outstanding example of unit bravery in modern warfare.” But the loss of the battalion was a hard pill to swallow. Ridgway said: “I cannot but feel a certain disquiet that down through the channel of command the full responsibility for realizing the danger to which this unit was exposed, then for extricating it when that danger became grave, was not recognized nor implemented. We must not lose any battalion, certainly not another British one.”

The actions of the 29th Brigade had cost the Communist offensive crucial momentum that would never be recovered. Although unable to hold Line Kansas, the Eighth Army’s fighting withdrawal was taking a huge toll of Communist troops. The enemy was also running short of supplies, and UN airpower was pulverizing them on the ground. On April 23, the Far East Air Forces flew more than 1,100 sorties, of which 340 were in close support of Eighth Army. During April 24-26, the pilots continued to fly more than 1,000 sorties a day, along with contributions from the U.S. Navy’s Task Force 77 fast carriers and the Marines. For the first time in the war, UN airmen provided tremendous close-support effort at night as well as by day.

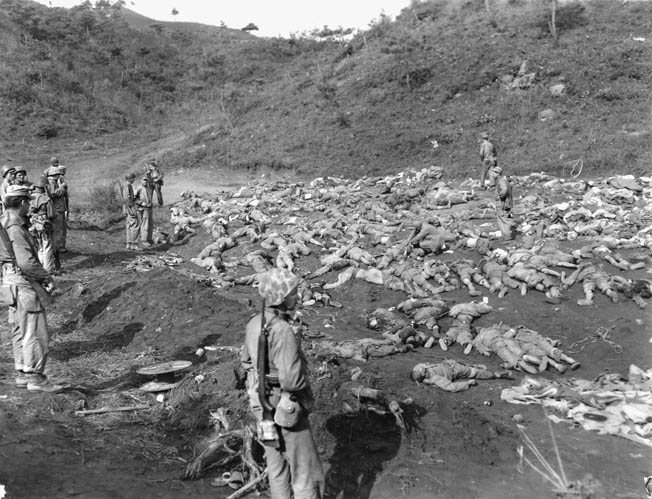

The Chinese tended to press their attacks at night, hoping to avoid the effects of aerial attack and concentrated artillery fire. On April 26, with I Corps still withdrawing through phase lines toward Seoul, a Time correspondent quoted one U.S. officer: “They attack and we shoot them down. Then we pull back, and they have to do it all over again. They’re spending people the way we spend ammunition.” An artilleryman stated, “The gullies in front of us are already full of Chinese dead, and we intend to keep adding to the pile.”

Establishing the No Name Line

On April 25, Van Fleet decided to set up a new transpeninsular defensive line, running from Seoul through Sabangu and on to Taepo-ri on the Sea of Japan. Uncharacteristically failing to give the new line a name, the Americans referred to it as the No Name Line. To establish it, the Eighth Army divisions needed to break contact and fall back as much as 35 miles from the original front line of April 22. In the vicinity of Seoul, the fortified defensive positions were known as Line Golden. Van Fleet sought to strengthen his forces in the western half of Korea while IX and X Corps in the center of the peninsula pulled back from around Chunchon to the Hongchon River. The 1st Marine Division was switched from IX to X Corps control.

The full force of the Communist offensive diminished after April 25, although heavy fighting occurred for several more days. During April 27-28, the Communists succeeded in outflanking units of the U.S. 3rd Division at the critical road junction of Uijongbu, and the division retreated to positions only four miles north of Seoul. The 1st ROK Division to the west was forced back down Route 1 to the northwestern outskirts of the capital. But Van Fleet’s No Name Line was in place by April 28-29, and the Communist advance was stopped. By April 30, the first step of the spring offensive was over, and Chinese and North Korean forces began withdrawing northward to reorganize. A no-man’s-land 10 miles wide opened up between the Communist and UN forces, and Van Fleet had Eighth Army divisions establish patrol bases five or six miles in front of their main lines of resistance. Probing attacks were made to determine enemy intentions, and by May 7, Uijongbu and Chunchon had been retaken. On May 9, the ROK I Corps, operating along the east coast of Korea, sent a tank destroyer battalion many miles north, temporarily occupying Kansong, where the northeast-running Route 24 joined the coastal highway.

For the most part, contact with the enemy during early May was limited, but resistance soon stiffened. Ridgway and Van Fleet considered launching a new general offensive of their own, but intelligence reports indicated that the Communists still had another shoe to drop. Only about half the Communist troop strength in Korea had been committed in their April offensive. Van Fleet believed another attempt by the Chinese to capture Seoul was in the offing. Ridgway later wrote: “General Van Fleet decided then to postpone the offensive and to strengthen his defenses to meet this fresh assault. Over five hundred miles of barbed wire were strung out along No Name Line. Mines were laid and drums of gasoline and napalm, which could be triggered by an electric contact, were added to the minefields. Fields of fire were carefully plotted and we were prepared to feed the enemy a dose of concentrated firepower such as had not been employed in Korea before.”

Van Fleet wanted the Eighth Army’s artillery to expend five times the normal rate of fire against enemy attacks. This became known as the “Van Fleet load.” Intelligence gleaned from prisoners and other sources indicated that by May 13 major Chinese units had begun shifting eastward from the west and west-central sectors. Still, the Eighth Army and X Corps thought that because of logistical difficulties it would be impractical for the Chinese to send a large force into the rugged Taebaek Mountains of eastern Korea. Marshal Peng believed otherwise, and by May 16 he moved five CCF armies into the sector between Chunchon and Inje along the Soyang River, behind the screen of the Chinese 39th Army and the North Korean III Corps. He intended to attack toward the southeast, annihilate the six ROK divisions on the eastern front, and destroy the U.S. 2nd Infantry Division. The Communist forces would then drive either south or west, aiming to capture the U.N.’s main supply depot at Pusan or slice in behind the Eighth Army in a deep envelopment. It was an ambitious plan, and Peng committed 175,000 troops to the initial attack, which struck on the rainy evening of May 16.

Modifying the No Name Line

The Chinese 27th Army began the assault by attacking at the seam between the ROK 5th and ROK 7th Divisions on X Corps’ right. Maj. Gen. Edward M. Almond, commanding X Corps, authorized the two divisions to fall back on the No Name Line, but the ROKs pulled out in disarray, opening up the flanks of the U.S. 2nd Division and the ROK III Corps. The 2nd Division, on its 15-mile front to the west, was hit by six CCF divisions. Van Fleet met with Almond at X Corps headquarters on May 17. Almond was grim. He told the Eighth Army commander: “The Chinese are flowing like water around my right flank. The Second Division is holding but the ROK divisions on my right, the Fifth and Seventh, are being disintegrated by this huge attack of the enemy, and this will continue on and be extended to the coast shortly, against the other ROK corps on the [extreme] right flank. I think we are in a very serious situation.”

Van Fleet ordered a shift to the right by the 1st Marine Division to enable the 2nd Division to swing its line southeastward toward a junction with the ROK III Corps on Line Waco, 12 to 18 miles south of the No Name Line. The ROK I Corps on the coast was also ordered to fall back to Line Waco. Van Fleet sought to bolster X Corps’ position by sending the 15th Regimental Combat Team of the 3rd Division to a threatened sector on the 2nd Division right, with the rest of the 3rd Division to follow shortly. More artillery was also sent to back up the line.

The ROK III Corps proved unable to effect an orderly withdrawal. With two divisions moving down the road from Hyon-ni toward Line Waco, the South Koreans were caught in a squeeze between a Chinese division that held a roadblock to the south and two North Korean divisions attacking from the north. Both ROK divisions broke away in disorder into the heights east of the road, leaving behind all their remaining artillery pieces and more than 300 vehicles. The routed South Koreans streamed toward Soksa-ri, well south of Line Waco.

On the X Corps front, the shifting of units left a deep salient with the 3rd Battalion, 38th Infantry at its apex on Hill 800 northwest of Hangye. To the west, the 1st Marine Division faced toward Chunchon. The 9th Infantry and 23rd Infantry of the 2nd Division held the line east of Hill 800, with positions extending far to the right of Route 24. This alignment became known as the “Modified No Name Line.”

The Battle For “Bunker Hill”

The battle for Hill 800 proved to be another classic action. The 3rd Battalion, 38th Infantry had worked on the hill’s fortifications for a week, constructing nearly two dozen bunkers on top of the hill. The Chinese attacked on the evening of May 17. A small-arms firefight erupted, with Chinese and U.S. troops wandering all over “Bunker Hill,” as it became known. Some Americans pulled out prematurely, and Lt. Col. Wallace M. Hanes, the battalion commander, met them at the bottom of the hill. “Get back on the hill,” he ordered. “We don’t give up a position until we’re beaten. And damn it, we’re not beaten and won’t be if every man does his share!” Chastened, his men drove off the Chinese.

The next night, the enemy attacked again. This time, Company K, on top of the hill, had effective communication with the supporting artillery. The company commander called in fire directly on the hill as his men positioned themselves inside the bunkers. The shells exploded a few feet above the ground, 2,000 rounds of 105mm fire bursting in an eight-minute period. The Chinese were slaughtered, but more came on. Company K called in still more artillery. During the night, the 38th Field Artillery Battalion alone fired more than 10,000 rounds in support of the 3rd Battalion. Finally, at 4 am on May 19, the Chinese broke off their attack, leaving Company K in sole possession of Bunker Hill. A decision was made at mid-morning of the 19th by the commanding generals of X Corps and the 2nd Division to withdraw the 38th Infantry from its salient in order to straighten and consolidate the X Corps line. Hanes protested, but his battalion abandoned the hill and took up positions to the south.

“The X Corps Had Led the CCF Into a Bottomless Pit”

Despite its gains, by May 19, the second step of the Communist spring offensive was running out of steam. The attack on X Corps and the 2nd Division, in particular, had been very costly. As during the April assault, the Eighth Army’s infantry and armor had been backed with a prodigious amount of artillery and air support. On May 17, the artillery of X Corps had fired some 38,000 rounds. Air strikes were coming at the rate of three to four an hour. The Communists were ground down. One observer commented, “By swinging wide the door but holding the hinges, the X Corps had led the CCF into a bottomless pit; it rushed into the valleys, ran short of ammunition and supply, and died in windrows under the pounding of UN air, artillery, and armor.”

This time, Ridgway and Van Fleet were ready with an immediate counterattack. Unlike in April, the Communist armies did not pull back on May 19. Instead, they were hit by a new Eighth Army offensive all along the line. In the west, I and IX corps moved north on May 20. X Corps and the ROK I Corps attacked three days later. Ridgway reported to the Joint Chiefs of Staff on the night of May 19: “Morale excellent. Confidence high.” He later wrote: “It was good sense to threaten and even to seize, if we could, the Iron Triangle, terminus of the formerly one good railroad from Manchuria and center for many good roads that kept the enemy’s front fed and supplied. It was also vital to us to control the Hwachon Reservoir, previously the source of water and electricity for Seoul and the heart of the enemy supply route. Consequently the new offensive was meant to roll on over the 38th Parallel again, without our giving that line any further thought, and to destroy as much as we could of the enemy’s potential.”

The blunting of the Chinese spring offensive amounted to the most decisive defeat the Communists had yet suffered in the war. The April attack had cost them at least 70,000 casualties, in comparison to UN losses of just 7,000. The Communists lost 90,000 more during the week of May 17-23. Meanwhile, the U.S. 2nd Division reported 900 killed and wounded, while inflicting 35,000 casualties on the Chinese in its battle south of the Soyang River. Van Fleet noted: “In June 1951, we had the Chinese whipped. They were definitely gone. They were in awful shape. During the last week of May we captured more than 10,000 Chinese prisoners.”

Despite pleading from Van Fleet and other commanders on the ground to hotly pursue the reeling Communist forces, President Truman decided against risking a wider war. The Soviet Union had begun making noises about intervening, and Truman did not want Korea to turn into World War III. Fighting would continue, but on a much smaller scale, while negotiators sought to wrap up the conflict across the bargaining table. It was now “war by other means.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments