By William E. Welsh

Highlander bowmen fired arrows that hissed through the air as they led the advance against the English as skirmisher sat the battle of Flodden. The English longbowmen fired back with telling effect. Tightly packed files of pikemen from the Scottish dales followed on the heels of the highlanders. Their flanks were covered by more highlanders wielding two-handed swords. French captains well-versed in pike assaults directed the attack led by two Scottish lords.

The pikemen surged through the gully at the bottom of the hill and crashed into the English line. Those in the front ranks, with menacing leveled pikes, wore sallets and armor to deflect the hailstorm of English arrows that peppered their ranks. Their bristling hedgehog of pikes bowled over the stunned shire levies in the front ranks.

Whatever resolve the levies of young Edward Howard’s division might have had quickly vanished on the late afternoon of September 9, 1513, on the fields of Branxton Moor in Northumberland. The few on the English right who dared stand up to the pikes were either spitted on their steel tips or trampled beneath the feet of hundreds of pikemen. Raw recruits gripped by terror cast aside their bows and billhooks to flee from the deadly pikes.

Scottish King James IV’s echeloned attack had begun auspiciously. The Scottish monarch watched with admiration from his position in the center of the Scottish battle line. If his follow-on divisions achieved similar success, the soldiers of his royal army might celebrate victory around their campfires that night.

By the standards of the Middle Ages, Scotland became a kingdom at the pace of other late-maturing realms, such as Germany and Poland. In the early medieval period, it was nothing more than a patchwork of minor kingdoms and tribal entities. But in the 11th century, these previously rival states became a bona fide kingdom. The reign of David I in the 12th century was an important milestone in the maturation of the monarchy; after his reign, the throne was passed in keeping with the rules of primogeniture.

Yet not every transition was smooth. When 13 Scottish nobles claimed the throne upon the death of Queen Margaret in 1290, King Edward I of England took advantage of the disorder to try to establish overlordship over the Scots. The concept was not new at all, for the English had considered themselves overlords of Scotland as far back as Anglo-Saxon times, when Scottish barons were vassals of the king of Wessex. But on the whole, the pugnacious Scots valued their independence. To help them resist the English, they forged a pact in 1295 with France against England.

The fear that both the Scots and French had of the powerful English army became acute during the Hundred Years’ War when Edward III invaded France. The Auld Alliance, as the pact was known, generally favored France. The French more than once manipulated the Scots into attacking the English to serve their own ends. Nevertheless, the Scots did not show any sign of wanting to withdraw from the alliance, and it was renewed frequently.

Following King Edward’s invasion of Scotland in 1296, the two kingdoms had been at war with each other intermittently. Even in times of peace, both sides engaged in destructive cross-border raids along the Anglo-Scottish frontier.

The Scottish monarchs in the 15th century sought to raise the prestige of their kingdom and make it an important player on the European stage. One way to do this was to purchase the latest military technology. When King James IV took the throne in 1488, he was keen to build an artillery corps and a large fleet.

James had a golden opportunity to test his new artillery in 1496, when disaffected Yorkists in England attempted to put a pretender on the throne. The Scottish king backed the pretender, Perkin Warbeck, and personally launched a cross-border raid that he hoped would show Tudor King Henry VII that he was unable to defend his northern border.

James IV’s raiders crossed the River Tweed at Coldstream on September 12, 1496, and immediately began wreaking havoc in Northumberland. Henry VII entrusted the defense of northern England to Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey, who was Lord Lieutenant of the Northern Marches. The elderly Surrey was the best general that England possessed at the time. Since he generally found border duty to be onerous, Surrey purposely avoided engaging the Scots because they were only conducting a raid as opposed to a full-blown invasion.

The Scots razed some towns and also destroyed a few towers and bastille houses before withdrawing. The English crown captured Warbeck the following year, marking the end of the Yorkists’ ill-conceived and poorly executed attempts to unseat Henry VII. Through his support of Warbeck, combined with his destructive raid into Northumberland, James IV had earned the animosity of Henry VII.

The two monarchs supposedly shelved their animosities in 1502 when they signed a peace treaty. The English king solidified the treaty by giving his daughter, Mary Tudor, to James in marriage. Although James favored keeping the peace with England, events on the European Continent drew the kingdoms into war.

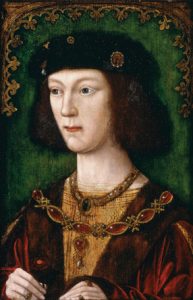

The long-running Italian Wars had embroiled France, the aggressor, into war with the Papacy and various Italian states. The Papacy assembled alliances, known as leagues, to combat French aggression. In 1511 Pope Julius II recruited Henry VIII of England, who had succeeded his father to the throne, to become an active participant in a newly established Holy League.

French King Louis XII invoked the Auld Alliance in an effort to get Scotland to distract England. He lured James IV into nullifying his treaty with the English with the promise of money and troops. Charles promised to give the Scottish monarch 50,000 francs, 2,000 infantry, and money for the Scottish fleet’s operations with the French fleet. James took the offer, for he believed the best way to elevate Scotland internationally was to join France in its war against England.

Henry VIII resolved to take the field against the French. He arrived in Calais and took command of the English invasion army on June 30, 1513. Before departing, the king confirmed Surrey’s position as the English commander in northern England. Surrey had a personal retinue of 500 drawn from his estates in East Anglia that were clad in the green and white livery of the Tudors. The earl directed his subordinate commanders to begin stockpiling supplies in Newcastle in mid-July. He was in London at the time, where he could maintain communications with the king. He mustered his retinue and led it out of Bishopsgate on July 22, bound for northern England. Surrey established a temporary headquarters on August 1 at Pontefract Castle in West Yorkshire. From that location, he issued summons to members of the northern gentry directing them to muster their retinues and recruit levies. Dispatch riders set out in August for each of the north shires to announce a general muster in Newcastle on September 1.

The French sought to dissuade the English monarch from his plans to wage war against France. They sent a herald to Calais on August 11 to inform the English monarch that their allies the Scots would invade northern England unless Henry desist from his preparations for war in northern France. Henry was not in the least dissuaded from his mission, for he had faith that Surrey could contain the Scots.

The Scots had mobilized before the English. James had issued a muster in July 1513 that required all men between the ages of 16 to 60 to respond to the call to arms within 20 days. A half century before Flodden, the Scottish parliament had passed an ordinance that replaced the infantry’s primary weapon, the 13-foot spear, with the 18-foot pike. The majority of the pikes were made by foreign artisans and arrived by ship in Scotland’s North Sea ports.

In a move that showed considerable foresight, James had previously established a harness factory at Stirling to produce high-quality, Milanese-style armor that could be worn by the Scottish infantry to lessen their exposure to the arrows fired by the English longbowmen in the event of war with England. Not all pikemen needed a full or even partial harness; those in the front ranks received top priority.

Also arriving by ship in July were 40 French captains skilled in pike tactics. They set to work immediately upon their arrival training levies from the Scottish lowlands. James issued orders for the army’s principal formations to consist of deep formations of pikes. The French captains took great pains to explain to the Scottish lords who would lead the pike formations into battle that it was necessary for the columns to maintain a rapid pace and strike the enemy with force in order to be successful. If the pike attack slowed or stalled, it was likely to end in failure.

James had assembled 42,000 troops by August 19, as well as his artillery corps, for his invasion of Northumberland. The Scottish army was made up of inexperienced levies from the lowland valleys, veteran borderers from the marches, and, most significantly, fierce clansman from the remote highlands. The clansmen, who were armed with bows and swords, did not train as pikemen; instead, James allowed them to fight as they had always done.

The Scottish royal army had 29 artillery pieces. Seventeen were heavy siege guns that hurled 60-pound shot. The balance consisted of two 18-pounder culverins, six 10-pounder demi culverins, and four 6-pounder sakers. Unfortunately, the Scottish gunners lacked the extensive training and experience possessed by the English artillery corps.

The size of James’ army was one of his key advantages. He had succeeded in assembling the largest and best-equipped army that Scotland had ever fielded against the English.

Five days later, the French and English skirmished in a half-hearted engagement known as the Battle of the Spurs. The battle came about when a French mounted force attempted to deliver supplies to the beleaguered garrison of Therounne, which was besieged by an Anglo-Imperial army. English cavalry and artillery turned back the French force, which had miscalculated the strength of the enemy forces screening Therounne.

Meanwhile, the Scots and English clashed in a brief but bloody skirmish in Northumberland. One of James’ top lieutenants, Alexander Home, Lord of Home and Warden of the East March, led a large mounted force on another raid into Northumberland in mid-August. While they were returning to Scotland through the Till Valley, they ran headlong into a well-laid ambush set by William Bulmer of Brancepeth, the High Sheriff of Durham. Bulmer had hidden 1,000 longbowmen in a brushy patch of ground near Milfield. When the Scottish rode into the kill zone on August 13, longbowmen fired sheets of arrows into the column of mounted Scots. As many as 500 Scots died or were severely wounded in the “Ill Raid” at a cost of just 60 English lives.

The two army commanders were a study in contrast. Surrey had a calm demeanor. When he applied himself, he showed himself to be industrious, methodical, and efficient. For his part, James was arrogant, self-indulgent, and overbearing. Whereas the lords from the border regions had considerable experience at low-intensity conflict, the highlander chiefs were brave yet unproven.

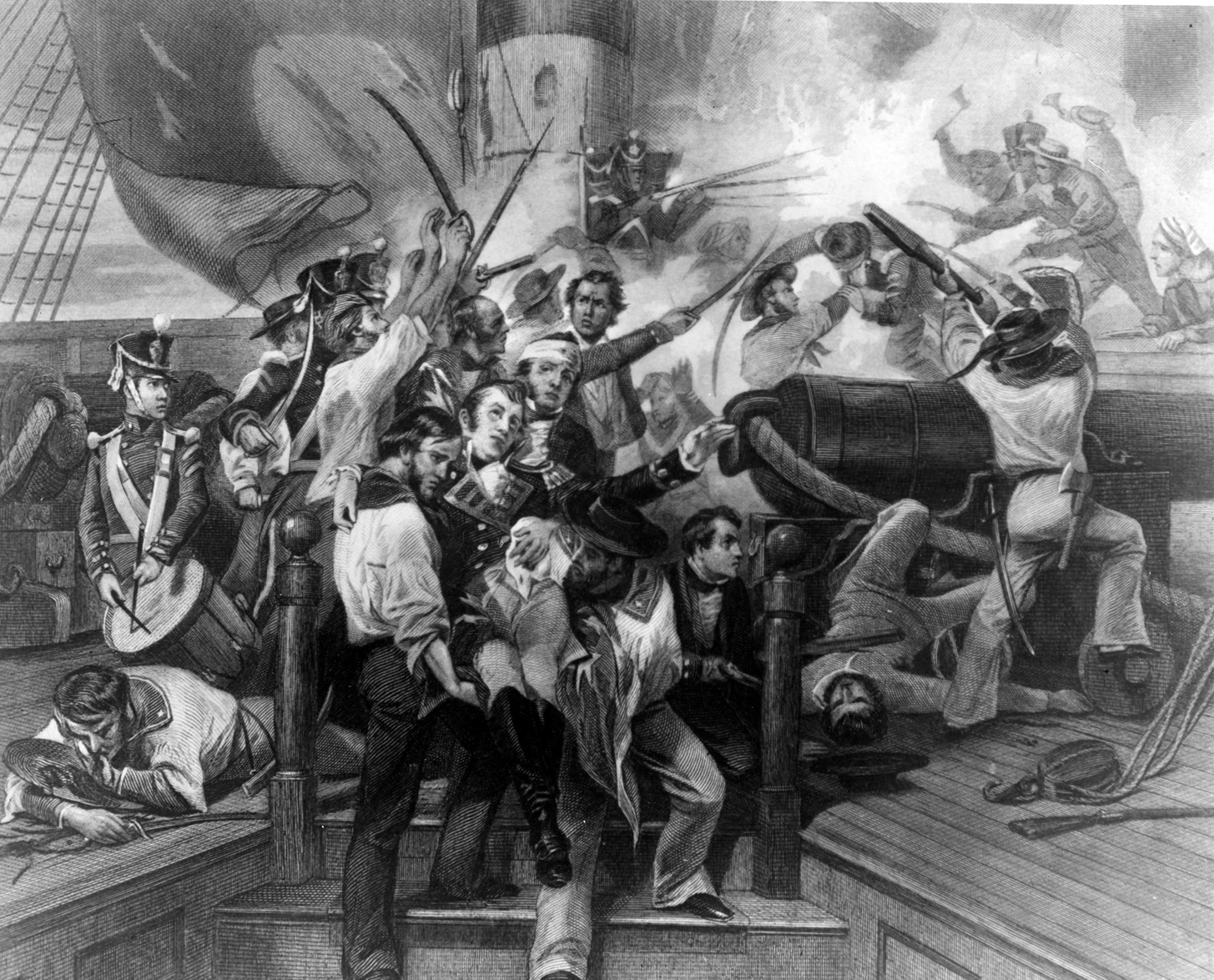

Ruins of Surrey had tight control over the core of his army given that two of his division commanders were his sons, the eldest 40-year-old Lord Admiral Thomas Howard and his third son Edmund Howard. Surrey’s second son, Edward Howard, had perished in a naval clash in Brest with the French fleet in April 1513. In an effort to elevate his youngest son, Surrey made him Marshal of the Horse.

The Scottish army crossed the River Tweed at Coldstream unopposed on August 22. Two days later the Scots besieged Norham Castle. The castle was of Norman design with a large keep. James deployed his siege guns on the north bank of the Tweed. The gunners opened breaches in the northern walls and also destroyed the western gatehouse.

Scottish foot soldiers stormed the breaches. The English defenders showered them with arrows and met their assaults with edged weapons in an effort to turn them back. Three times the Scots charged, and each time the English prevented them from breaking through their makeshift defenses. But when no English relief force arrived to rescue the garrison after a week of fighting, castellan John Anislow struck his colors on August 29.

The Scottish king then proceeded along the east bank of the Till River to both Etal and Ford Castles. He set up his headquarters at Ford Castle to await Surrey’s move. Marching further south into England made no sense, for James’ strategy was to draw Surrey’s army as far from London as possible. The weather grew cold and rainy, making marching difficult for both armies. Surrey faced a formidable task getting his army assembled given that it had to march along muddy roads and narrow lanes. By the time Surrey had assembled his army, James had taken up a strong defensive position atop Flodden Edge.

James’ lost about one-third of his force when troops who had obtained booty from the plundered towns and strongholds departed for their homes. Most of the deserters were highlanders, who were not accustomed to long service.

Surrey, who was at Pontefract when he learned that James had invaded England, departed for York the following day. He paused in York for three days before moving north to Durham, where he took possession of the sacred banner of St. Cuthbert. The English had carried the banner into war with the Scots since the time of Edward I. Surrey then proceeded to Newcastle. He arrived in the northern city on August 30 to take command of 22,500 troops.

Surrey’s troops were drawn from the retinues of the northern nobility, bishoprics of Durham and Whitby, and the counties of Yorkshire, Cheshire, and Lancashire. The entire army consisted of billmen and longbowmen, except for 1,500 horsemen drawn from the border marches. The billhook came into use with the widespread adoption of plate armor in the late 15th century. Derived from the agricultural tool, the weapon had a traditional head with a blade that curved outward. Each part of the versatile billhook served a different purpose. Soldiers used the heavy curved blade to chop and slash at their opponents much like an axe, they used the spike on top to thrust at opponents like a pike or spear, and they used the hook on the back to snag the weapons of their opponents and yank horsemen from their saddles. Unlike pike formations, billmen required no training.

Surrey’s artillery train consisted of a well-trained, 400-man artillery corps. Led by Sir Nicholas Appleyard, the English artillery corps included 22 guns— eighteen 2-pounder falcons and four 4-pounder serpentines. Although these were much lighter than the heavy Scottish siege guns, they were more maneuverable on the field. Their maneuverability made them well-suited to counter-battery fire.

Surrey faced three major challenges when it came to fielding an army against the Scots. First, the bulk of his army consisted of levies. Second, he did not have high-quality weapons and equipment to distribute to his troops, and therefore they would have to get by with the weapons they owned or could borrow. Third, he had to bring the enemy to battle quickly, for he lacked food stores with which to feed his army as well as tents and blankets to protect them from inclement weather if there were to stay in the field through the autumn months.

Surrey led his army north from Newcastle on August 31. He halted on September 4 at Bolton, near Alnwick, having covered 34 miles. He ordered his banners unfolded and convened a council of war.

The following day English scouts brought word that the Scottish army held a strong position at Flodden Edge. The ridge on which the Scots were deployed rose 500 feet above the surrounding plain. Attacking a larger foe in a defensive position on high ground was a recipe for disaster, so Surrey decided to manuever in such a way as to draw the Scots from their position. As he worked out his strategy, additional mounted troops arrived in the English camp on September 7 led by John “The Bastard” Heron, a seasoned English border reiver. Surrey ordered Heron to join the main body of border light horsemen under Dacre.

While heralds conveyed messages between the two armies, Surrey made preparations to execute a wide flanking march that he hoped would compel the Scots to abandon Flodden Edge since it would bring the English into position behind the Scottish army. Surrey’s army, which was 30 miles from Flodden Edge, set out on September 8 on the maneuver. When the English host reached the River Till, it crossed to its north bank and continued for eight miles. Surrey halted his army for the night at Barmoor. He selected the site because an intervening hill, known as the Watch Law, blocked the line of sight from Flodden Edge to the English encampment. By so doing, he hoped to keep the Scots unaware of his approach.

The English resumed their long flank march the following morning. Surrey led the army north and then west. He intended to recross the Till to its south bank. This would place the English astride James’ line of communications to Scotland. Surrey divided his army at Duddo Village, sending the Lord Admiral with the vanguard and artillery on a longer march to cross at an upper ford, while Surrey with the main army crossed at nearby Heaton Ford.

Scottish scouts located the English army that morning. After crossing the Till, both halves of the English army then crossed a stream known as the Pallinsburn and deployed into line of battle near Branxton village. To meet the English, James abandoned Flodden Edge and ordered his armies to advance a mile north to Branxton Edge and redeploy facing north. In James’ mind, he could still fight a defensive battle if the English tried to pry him from Branxton Edge; however, his new position was less formidable than his original one.

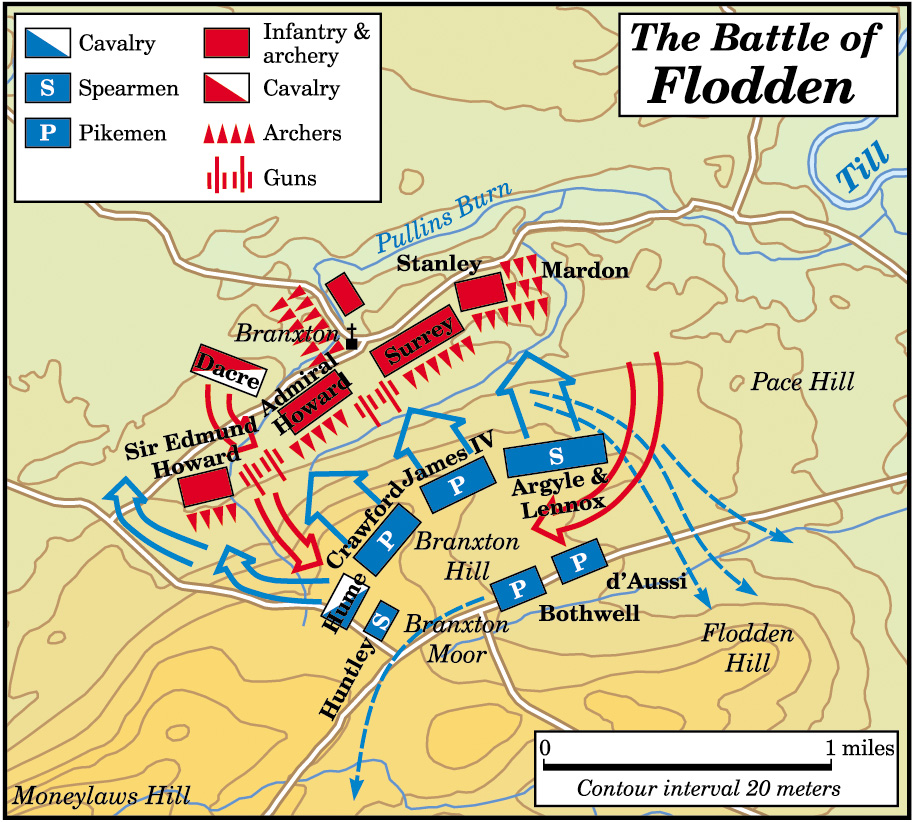

The two sides prepared for battle. James ordered Lord Alexander Home’s borderers and Lord Alexander Gordon’s highlanders—10,000 troops—to deploy on the left. The 7,000 troops of three nobles—William Hay, Earl of Errol; John Lindsey, Earl of Crawford; and William Graham, Earl of Montrose—collectively known as the Scottish Division, deployed in the center. James IV’s 15,000-strong King’s Division took up position on the right.

Two other divisions served as the Scottish reserve. The 5,000-strong Highlander Reserve, led by Archibald Campbell and Matthew Stuart—the earls of Argyle and Lennox, respectively—deployed to the right rear of the King’s Division to cover its right flank. The 5,000-man Lowland Reserve, led by Adam Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell, assembled in the center behind the Scottish Division. The majority of the Scottish troops served as pikemen; however, James allowed the highlanders to fight according to their traditions with their claymores, two-handed axes, and bows.

The English host deployed with the 3,000 men under Edmund Howard on the right, the 11,000 men under the Lord Admiral in the center, and 5,000 troops under the Earl of Surrey on the left. Another division of 3,000 troops, under Sir Edward Stanley and Sir Marmaduke Constable, was assigned a support role on the extreme left flank. Lastly, Warden-General of the Northern Marches Lord Thomas Dacre’s 3,500 cavalry served as the English reserve. Dacre’s light horsemen from the border regions were known as prickers.

Stanley was an experienced commander. He held the lifetime position of High Sheriff of Lancashire and also was the Commissioner of Array for Yorkshire and Westmoreland. The majority of his troops were fleet-footed archers skilled in the use of their longbows from a lifetime of practice. Unfortunately, they would not reach the battlefield until dusk.

Both armies positioned their artillery in front of their divisions. In the mid-afternoon the English began bombarding the Scottish line-of-battle to its south. The highly effective fire of the skilled English gunners dismantled Scottish guns. The Scottish gunners fired back, but did not do comparable damage to the English.

Those Scottish gunners who survived the initial bombardment quit their guns once it became apparent they could not compete with the English gunners. After Appleyard’s gunners had silenced the Scottish guns, he ordered his men to begin shelling the Scottish pike formations. Although the casualties were not heavy, the roundshot produced horrific wounds and gruesome results that discomfited the Scotsmen as the balls bounded into the Scottish pike files. During the course of the artillery duel, the English succeeded in killing the Scottish artillery commander.

The Scottish foot soldiers grew increasingly restless under the vicious bombardment. Although James had wanted to receive the English attack with his troops in an advantageous position atop to Branxton Edge, it became evident to him that he would have to order an attack against the English lines in order to retain the morale of his troops. Surrey had not only forced James to abandon a perfect defensive position on Flodden Edge by his strategic flank march, but also silenced the Scottish guns.

James devised an en echelon attack against the English. One of the basic concepts behind attacking en echelon was to compel the defender to commit his forces against each advance, thereby leaving an easier path for the next advance in line. The pikemen in the front ranks had protection ranging from full or partial plate armor to less expensive padded jacks and brigandines. Those wearing the jacks and brigandines also had “splents,” or splint armor, which consisted of metal strips that attached to their arms and to their legs like greaves, according to The Trewe Encounter or Batayle Lately Betwene Englande and Scotland, a contemporary account of the battle.

The success of the Scottish pike attack depended on whether James’ divisions could maintain their speed of advance. Although they would have initial momentum moving down the north slope of Flodden Edge, there was a marshy gully at the base of it. Although the gully was not so pronounced in front of the Scottish left, its sharp dip in front of the rest of the Scottish position would prove to be a significant impediment to the pikemen of the middle and right divisions.

James issued orders for the division on the left to advance at 4:30 pm The Scots advanced “in good order … without speaking a word,” according to the Trewe Encounter. They attacked “in great plumpes, part of them quadrant [i.e., square or rectangular] and some pikewise, that is being more wedge-shaped to the front,” stated the chronicle.

The division of Lords Home and Huntly that led the attack on the Scottish left outnumbered Edmund Howard’s division opposite them by two to one. Lord Home’s well-delivered pike attack shattered the cohesion of the shire levies.

Even before the Scottish advance, the Cheshire levies fighting under Edmund Howard felt a great sense of unease. This stemmed from their having to go into battle under the youngest Howard when their regarded Lord Stanley as their rightful commander. They had hoped to go into action under Stanley’s eagle-claw banner, but the Earl of Surrey had directed otherwise. They resented the youngest Howard and had no faith in him.

The Cheshire levies had to contend not only with Lord Home’s pike squares, but also with the fury of Lord Huntly’s highlanders, who moved against their flanks swinging their claymores and battle axes. Once the English levies’ cohesion was shattered, the Scottish highlanders began a dreadful slaughter of the billmen on the English right. “[The Scotsmen were] such large and stout men that one would not fall when four or five bills struck them,” wrote Bishop Thomas Ruthal of Durham to Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. Many of the Cheshire levies in Edmund Howard’s demoralized division fled for their lives.

Surrey watched the crisis unfold on his right. As his younger son’s division crumpled, he committed Lord Dacre’s prickers to shore up his right wing. Dacre’s prickers launched a furious counterattack on horseback and succeeded in stabilizing the remnants of the shattered division. The Bastard of Heron’s horsemen rode into battle with the prickers. When Heron spied Edmund Howard wielding his hand-and-a-half sword against several highlanders who were trying to capture him, Heron and his men drove off the highlanders and escorted the youngest Howard to safety.

The bloody beginning of the great contest at Flodden had not been without a cost to the Scots, for some of the more stout-hearted billmen had slain three of Home’s kinsmen from the Scottish upland dales, as well as four senior Gordon highlanders.

The troops of the Scottish Division advanced just minutes after the division to its left went forward. It rolled down the northern slope of Branxton Hill to assail the Lord Admiral’s troops in the English center. The Scotsmen in the ranks hailed from Perthshire, Angus, Fife, and the northeastern Lowlands.

When the Scottish Division reached the marshy stream at the base of the ridge, though, it lost its forward momentum. The ranks split in places with men struggling to get through the marshy ground that pulled at their feet. Making matters worse, the Lord Admiral had placed the bulk of his troops on a rise known as Piper’s Hill. The difficulty of crossing the gully combined with the effort needed to ascend Piper’s Hill robbed the Scottish Division of its forward momentum.

Despite showers of arrows fired at them at them by the Lord Admiral’s archers, the well-armored pikemen in the front ranks of the second division struggled uphill hoping to wreck the English center. “Unless [the arrows] hit them in some bare place, [they] did them no hurt,” stated Hall’s Chronicle, penned by 16th century English historian Edward Hall. Bishop Ruthal echoed Hall’s Chronicle, “[The Scots] were so well cased in armor that the arrows did them no harm.”

In an effort to rally their pike squares, the three Scottish earls shouted encouragement to their men, exhorting them to show their king that they were sturdy and reliable soldiers. Yet the division’s attack floundered at the crest of Piper’s Hill. Having resolved not to suffer the fate of the Cheshire levies, the Lord Admiral’s troops rose to the occasion. Some succeeded in fighting their way into the Scottish ranks, forcing many of the Scots to drop their unwieldy pikes and fight with their swords. The Scots wielding swords were outfought by the English with their much longer billhooks.

The fighting atop Piper’s Hill rose to fearsome heights of bloody carnage, but the Scots never gained an advantage. It was a textbook case of a failed pike attack. Having gained an advantage over the Scots, the Lord Admiral’s troops made the most of it. All three of the stalwart Scottish earls fell in hand-to-hand fighting with the Lord Admiral’s 500 crack retainers and the billmen. The success enjoyed by the English center owed much to Lord Admiral’s charisma and steadfast leadership.

“Our bills shortly disappointed the Scots of their [pikes],” wrote Bishop Ruthall, adding that the Scots “could not resist the bills that lighted so thick and sore upon them.” In the face of the struggle with the Lord Admiral’s billmen, the Scottish Division ultimately collapsed.

James could do little to reverse the setback in the center of the battlefield, for he still had to contend with the Earl of Surrey’s division. Like the two divisions to his left, James’ division swept down the northern slope of Flodden Edge at 4:45 pm His pikemen also lost their forward speed trying to cross the slushy ground at the base of the hill.

Nevertheless, the sheer size of the King’s Division would make it difficult to defeat. In a skilled move that only a gifted commander could devise, Surrey had ordered his front ranks to pull back far enough to buy time for the Lord Admiral to redirect a portion of his troops to assail the exposed left flank of the King’s Division. As Scottish pikes in the King’s Division advanced in a giant wedge, the Lord Admiral’s archers thinned their ranks. The longbowmen fired their deadly arrows at short range into thick mass of Scottish foot soldiers. The fighting ebbed and flowed on that part of the battlefield, but the English eventually prevailed. As the Scots in the front ranks were forced back, many of those at the back threw down their weapons and ran believing the day was lost.

Unfortunately for James, the reserve division led by Lennox and Argyll failed to come to his aid. The reason for this is unknown. One the one hand, the earls might not have received explicit orders to come to the king’s aid. On the other hand, they may have believed the day was lost and been unwilling to commit their highlanders to a hopeless cause. James probably expected the two reserve divisions to come to his aid without having to make a request. The Scottish king did send an urgent order to lords Home and Huntly, who had rallied their remaining troops, to come to his aid. But Lord Home flatly refused to obey the order. Huntly raged at him, but could not get Home to change his mind.

Yet the Earl of Bothwell did commit his reserve at 5:30 pm The commitment of these troops did not alter the course of the battle because they were not deployed in an effective manner. Rather than maneuvering to strike an English flank, Bothwell sent them straight into the rear of James’ troops, where they became mingled with those who were quitting the field. Confusion ensued as the Scots from the reserve collided with desperate soldiers determined to save their hides. Bothwell did nothing to try to rally the fleeing troops. Meanwhile, the English billmen and archers began encircling the Scottish army.

Lord Stanley and his troops did not reach the field of battle until 6:30 pm He later attributed his delay to his inability to find a local guide to lead his troops to the field of battle. The High Sheriff of Lancashire had craftily ordered his archers to approach the battlefield over dead ground; that is, across ground hidden from Scottish observers by an intervening knoll. They caught the highlander reserve, positioned behind the Scottish right, by complete surprise.

Shooting as they advanced, Stanley’s crack archers felled large numbers of lightly armored highlanders. The surviving highlanders fled west, where they stumbled into the Scottish pikemen, minus their unwieldy pikes, retreating from the main battle. Some of the highlander chieftains tried to rally their troops, but by that time it was clear the English had won the day. The English took few, if any, prisoners; neither side granted quarter to the other on this occasion.

In a circle of Scots that were still fighting at 7:00 pm, James IV fell dead to the ground. At first the Scots were unaware of the king’s death. But when they realized he had fallen in combat, they lost the last ounce of their morale. The day belonged to the English. In the gloaming, the English took possession of the Scottish artillery. By capturing the enemy guns, Surrey’s army had won a great prize that would make their victory even more treasured.

Flodden was a cataclysmic defeat for the Scots. King James IV had risked everything by committing the manpower resources of his kingdom to one major battle. The Scots lost 10,000 men, while the English lost just 1,500.

In addition to James’ death, other high-born Scotsmen who died on the field were nine of the country’s 21 earls, 14 of the 20 lords of the Scottish Parliament, and 300 gentry. The Scottish army also lost many men of the cloth who went into battle, including Alexander Stewart, Archbishop of St. Andrews; George Hepburn, Bishop of the Isles; two abbots; and the Dean of Glasgow. Lords Home, Huntly, and Lindsey cheated death and survived the carnage. Yet the Scottish Parliament would later charge Home with treason, and he would be eventually beheaded for his treachery at Flodden.

Lord Dacre found James’ half-stripped body, which had been plundered by English commoners. Surrey ordered the king’s corpse shipped to London.

The English victory at Flodden was a tribute to the leadership of the Earl of Surrey and the Lord Admiral. It was also a tribute to the skill of the English artillerymen. Lastly, it was a sterling tribute to the steadfastness of the English billmen, the majority of whom had not flinched even though they were substantially outnumbered.

The Scots wanted revenge for their defeat at Flodden, but squabbling among Scottish lords dashed any hope of another military campaign. In the wake of the king’s death, the Scottish Parliament appointed Duke John of Albany to serve as regent for James’ infant son. The Holy League disbanded in March 1514. England and France signed a treaty that year by which the French agreed to cease all aid to the Scots.

King Henry had depleted the English war chest, and because of this there was no thought of continuing the war against the Scots any longer than necessary. His victory at battle of Flodden during the War of the Holy Leaguewas the greatest defeat of Scottish arms in the kingdom’s history.