By Pat McTaggart

In the latter half of 1943, the German Wehrmacht had seen disaster follow disaster on the Eastern Front. After the Battle of Kursk in July, the Red Army had gained the initiative, its troops and commanders hardened by two years of bitter struggle.

Gone were the days of mass surrender by Soviet troops, poorly armed and poorly led. The Red Army was now up to the task of taking on the Germans head to head, for it had finally learned the lessons that had once made the German Army a nearly invincible foe in the struggle for Eastern Europe.

In the central sector, Soviet forces gained more than 400 miles as they pushed the battered units of Heeresgruppe Mitte (Army Group Center) west from Voronezh to Kiev. In the south, Heeresgruppe Süd (Army Group South) had lost another 400 miles of some of the richest land in the Soviet Union, located between the Don and Dnieper Rivers. One bright spot, at least in the German point of view, was that the siege of Leningrad was still in progress. The Russian summer and fall offensives of 1943 had left the divisions of Heeresgruppe Nord (Army Group North) virtually unscathed. As the new year approached, all that was about to change.

The Leningrad sector had remained static for several months, each side launching intermittent probing attacks instead of major assaults. For 28 months, the Germans had held a stranglehold on the city, bombing and shelling block after block and causing thousands of casualties.

In Moscow, Premier Josef Stalin and his Red Army High Command (STAVKA) were planning a January surprise for the men of Field Marshal Georg von Küchler’s Heeresgruppe Nord. Two Soviet Army fronts were assembling a massive number of men and materiel to break the siege of Leningrad once and for all, hopefully destroying Col. Gen. Georg Lindemann’s 18th Army in the process.

From the city itself, General L.A. Govorov’s Leningrad Front would attack with the 42nd (General I.I. Masslennikov) and 67th (General V.P. Sviridov) Armies, while the 2nd Shock Army (General I.I. Fedyiniskiy) would strike out from the Oranienbaum Pocket, a Soviet-held bulge along the Gulf of Finland. Farther south, General Kiril A. Meretskov’s Volkhov Front planned a three-pronged assault, with the 8th Army (General Sukhomlin, replaced by General F. N. Starikov on March 1) hitting the Germans near Mga, the 54th Army (General S.V. Roginsky) attacking the Volkhov River line, and the 59th Army (General I.T. Korovnikov) smashing the Novgorod sector.

STAVKA planned a Stalingrad-type operation, with the two fronts forming a gigantic pincer to envelop the 18th Army with fast-moving armored and mechanized forces. The following infantry divisions would then finish the job. Lindemann’s divisions, about 20 in all, would face Red Army forces that outnumbered the Germans 3 to 1 in infantry (55 rifle divisions, nine infantry brigades, and eight tank brigades), 3 to 1 in artillery, and 6 to 1 in tanks, self-propelled artillery, and aircraft.

German intelligence was surprisingly inept in discovering this massive Soviet buildup. During the fall of 1943, Heeresgruppe Nord was being used as a reserve for the rest of the Eastern Front, with several top-rate divisions being sent elsewhere to try and stem the Russian offensives in other areas. Von Küchler grew increasingly uneasy as he saw many of his best divisions being replaced with second-class infantry and Luftwaffe field divisions, made up of inadequately trained Luftwaffe personnel that were no longer needed to maintain the dwindling German Air Force.

The Germans were constructing a secondary line, known as the Panther Line, in case the Russians forced Heeresgruppe Nord to retreat. Beginning at the Gulf of Finland, the position ran along the Narva River and Lake Peipus southward through Pskov and beyond Vitebsk. As the new year approached, the Panther Line was still incomplete in several areas, and the constant “borrowing” of divisions from the Heeresgruppe would make occupation and defense of the position an uncertain gamble at best.

The Soviet hammer fell on the night of January 13-14 as more than 100,000 shells from the Oranienbaum Pocket struck the divisions of Obergruppenführer (Lt. Gen.) Felix Steiner’s III SS Panzer Corps. Minutes after the barrage lifted, hundreds of tanks and thousands of Red Army infantry surged out of the pocket. Brig. Gen. Hermann von Wedel’s 10th Luftwaffe Field Division was the first German unit to get hit by the Soviets. Within hours, the division had disintegrated into a mass of fleeing troops.

Colonel Ernst Michael’s 9th Luftwaffe Field Division suffered the same fate. The German front before Oranienbaum had been torn asunder, leaving a gaping hole in Lindemann’s left flank through which additional Soviet divisions poured. Lindemann called for his only reserve, Maj. Gen. Günther Krappe’s 61st Infantry Division, to move forward, but it would take two agonizing days before the division could become engaged.

On the Leningrad Front, Govorov launched his attack the following day with a massive bombardment on the L and LVI Army Corps, hitting the Germans with more than 220,000 shells. Masslennikov’s 42nd Army attacked, managing to overrun the German forward positions before getting hit hard from the German corps artillery. By day’s end, the Soviet advance in front of the city measured 2.6 kilometers.

The staggered assault continued as Meretskov’s Volkhov Front hit the Germans. In the 59th Army sector, General Korovnikov ordered his 6th and 14th Rifle Corps (five infantry divisions and one infantry brigade) to take the German positions north of Novgorod, which was manned by General Kurt Herzog’s XXXVIII Army Corps (1st Luftwaffe Field Division and 28th Jäger Division). The Germans resisted fiercely, but as more Soviet reserves were pushed through gaps in the lines, their position became hopeless. It was the same story in other sectors attacked by the Volkhov Front.

Bad weather following the opening of the offensive masked the true nature of the Soviet offensive. Aircraft on both sides were temporarily grounded, and German intelligence incorrectly perceived that the Russians had shot their bolt. It was a costly error. When the skies cleared on the afternoon of the 16th, the Red Air Force began a campaign to pulverize every enemy position that could be seen. The Luftwaffe was in such a weakened state throughout the northern sector that it could do little to stop the slaughter.

On the Oranienbaum Front, Steiner’s III SS Panzer Corps was fighting for its life. Regardless of losses, the Red Army pushed forward. The 90th Infantry Division’s Sergeant Morozov was badly wounded but held his ground against a German counterattack. Other men sacrificed themselves by throwing their bodies against the slits of enemy bunkers so that the Germans could not fire on their advancing comrades. They included Private I.N. Kulikov, 2nd Lt. Volkov (131st Guards Regiment), A.F. Tipanov (64th Guards Infantry Division), and Sergeant Skudrin of the 98th Infantry Division. Each won the title “Hero of the Soviet Union” for his sacrifice.

The Russians kept up their attacks, funneling reserves to the front to make up for the high casualties they were taking. By January 18, it was clear to von Küchler that his entire northern flank was collapsing and that several divisions were in danger of being surrounded and annihilated. In Berlin, Hitler ordered the line to be held with little regard to the sheer numbers facing his troops.

Counterattacks were ordered, especially in Steiner’s sector. Limited successes were made by Sturmbannführer (Major) Fritz Bunse’s 11th SS Pionier (Engineer) Battalion and Obersturmbannführer (Lt. Col.) Hanns-Heinrich Lohmann’s III/ Rgt. “Norge” of the 11th SS Panzergrenadier Division “Nordland.” Both men were awarded the Knight’s Cross for their actions, as was 23-year-old Untersturmführer (2nd Lt.) Georg Langendorf, commander of the 11th SS Aufklärungs Abteilung’s (Reconnaisance Unit) 5th Company.

In a letter to the author, Langendorf recalled his unit’s actions: “We had a total of six anti-tank guns at our disposal, and the men had done an excellent job of camouflaging their positions. In the distance, a Soviet column of 54 tanks was advancing towards (us). I ordered the men to hold their fire until each had several clear shots. When we commenced firing, there were exploding tanks everywhere, and when Ivan finally retreated, we had destroyed all but four of the vehicles.”

Brigadeführer (Maj. Gen.) Fritz von Scholze’s 11th SS Freiwillige (Volunteer) Panzergrenadier Division Nordland was clearly the backbone of Steiner’s III SS Panzer Corps. Formed in mid-1943, the division was truly international in character. Danes and Norwegians formed the largest contingents with a combined total of about 2,000 officers and men. Other countries represented within Nordland’s ranks included Estonia, Belgium, Holland, Sweden, and Switzerland. There were also Volksdeutsch (ethnic Germans) from Romania, Latvia, Lithuania, Croatia, and the Ukraine to augment the German core of the division.

Another important element of Steiner’s corps was the 4th SS Freiwillige Panzergrenadier Brigade Nederland, which was mostly made up of Dutch volunteers under the command of the German SS Oberführer (Senior Colonel) Jürgen Wagner. The unit had been on the Volkov and Leningrad Fronts since January 1942, and its combat-hardened veterans would, along with Nordland, form the backbone of the German forces at Narva.

With things going from bad to worse, von Küchler saw the imminent threat posed by a link up of the 2nd Shock and 42nd Armies, which would cut off several German units pinned against the coast of the Gulf of Finland. He ordered the XXVI Army Corps to make a withdrawal of about 30 kilometers to avert that situation, infuriating Hitler in the process. By the time Berlin heard about the order, the withdrawal had begun, lifting the siege of Leningrad after almost 900 days.

Some units along the coastal sector managed to escape, but others were caught by the Russian juggernaut and simply disappeared. Meanwhile, von Küchler was summoned to Hitler’s headquarters to explain his actions. While the Führer and the general argued over withdrawals and the effectiveness of the Panther Line, the Soviets continued to drive forward.

During the final week of January, the Russians took Pushkin and Slutsk. The vital supply center of Krasnogvardeysk met the same fate as the 18th Army continued to disintegrate. With all of Heeresgruppe Nord threatened with annihilation, Hitler replaced von Küchler with one of his favorite commanders, Col. Gen. Walter Model.

Model was a good defensive general who had been a loyal follower of Hitler for many years. Because of their relationship, Model knew that he would have at least a few days of freedom before Hitler started to interfere with his plans. He persuaded the Führer that a general withdrawal to the Panther Line was the only way to save the Heeresgruppe, something that von Küchler would probably have never been able to do. Once the order was given, it became a race against time to occupy the line before the Soviets were able to overrun the severely undermanned defenses.

As German forces started pulling back along the entire Leningrad front, the weak units working on the Panther Line worked frantically to strengthen its defenses. In Steiner’s sector, the retreat was methodical, with elements of other shattered German units joining the withdrawal. Soviet forces were kept at arm’s length by sharp counterattacks against Russian advance elements. By the end of January, the retreating Germans had won the race. The battle for the Narva bridgehead was about to begin.

During the more than 150-mile retreat, some advance units were sent to strengthen Narva’s defenses. One such unit was led by Sturmbannführer (Major) Wilhelm Schlütter, commander of the Nederland’s artillery regiment. In a letter to the author some 40 years later, Schlütter described his preparations for his unit: “I and my staff worked side by side with the enlisted men. That was how it was. Our hands got just as bloodied and calloused as the lowest private, because we all knew that time was of the essence. We had little time to do things by the book. The important thing was the safety of our guns, so we dug our trenches and built bunkers with great care, using every available material to camouflage them.”

The Narva line was important to the Germans both militarily and politically. If it fell, the entire Panther Line would be exposed to attack. It was also one of the last bastions in what was once Old Russia. If Narva fell, the Ukraine, Belorussia, and the Baltic States would be in danger of falling into Stalin’s hands.

Politically speaking, if Narva and the Baltic States fell, Germany would probably lose its Finnish ally. With German forces fighting on the Murmansk front, a Finnish defection could prove disastrous and might possibly open the way for Soviet domination of northern Norway and its vital nickel mines.

Consistent with German military doctrine, a reinforced bridgehead was established on the eastern bank of the Narva River, across from the city itself. During the first days of February, elements of the Nordland and Nederland fortified the bridgehead, as well as the Narva River Line itself. SS Pioniere (Engineer) units worked alongside the infantry to make certain that their defenses were as strong as possible. When finished, the Narva bridgehead had a seven-mile frontage running from north of Lillienbach, south to the village of Dolgaja Niva.

As the mangled remnants of other units found their way to the city, they were positioned to the north and south to set up their own defensive networks. These units would play a vital role in the upcoming battle, but it was the SS that had the responsibility of defending Narva itself.

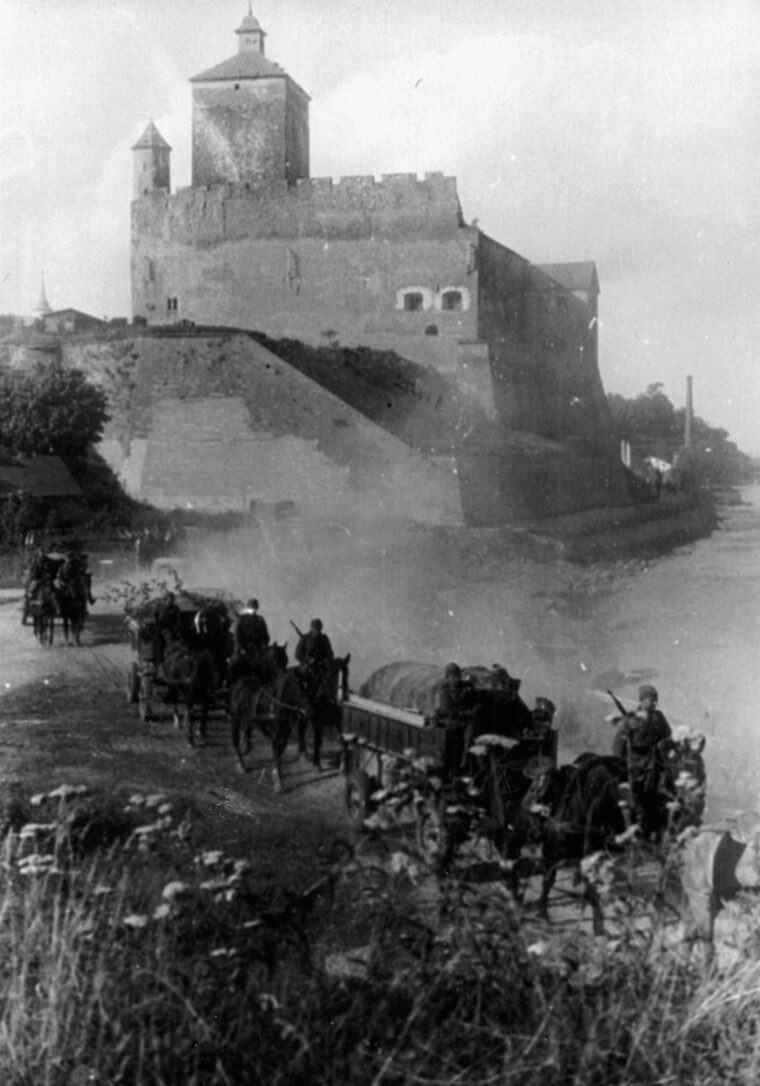

Narva was an ancient city, scarred by war almost from its founding. The Danes controlled it in the 13th century, followed by a period of occupation by the Teutonic Knights, who built a huge castle, Hermannsburg, on the western bank of the river. During the Great Northern War, the area around the city became a battleground as the forces of Charles XII of Sweden and Peter the Great clashed. In later years, Ivan III built a castle named Ivangorod directly across the river from Hermannsburg to house Russian troops.

Soviet advance elements had almost beaten the Germans to the Narva, and more troops were on the way. While the Germans worked feverishly on their defenses, they came under artillery fire. Obersturmbannführer (Lt. Col.) von Westphalen, commander of Nordland’s 24th Regiment Danmark, reported that his unit was under almost constant fire on the southern sector of the bridgehead and a large enemy buildup was observed by units of Nederland, which held the northern sector.

The Russians moved to establish their own bridgeheads on the western bank of the river on February 3. North of Narva, Soviet forces crossed the river, initially meeting light resistance. Von Scholze reacted quickly, sending Oberstumbannführer Paul-Albert Kausch’s SS Panzer Abteilung 11 Hermann von Salza (HvS) to the scene. With the help of a platoon of Tiger tanks commanded by Leutnant Otto Carius, the bridgehead was destroyed.

A bigger concern was an incursion by the 8th Army south of the city. Sukhomlin sent a large force across the river near Krivasao, routing outposts of Maj. Gen. Walter Krause’s 170th and Maj. Gen. Wilhelm Berlin’s 227th Infantry Divisions. Both units were sorely under strength, and the Soviets were able to make good headway, advancing to within reach of a railroad supply line near Vaivara.

Steiner rushed fragments of Maj. Gen. Günther Krappe’s 61st Infantry Division and Maj. Gen. Otto Kohlermann’s Panzergrenadier Division Feldherrnhalle to the scene in an effort to stop the Russians. Supporting the ragtag units was Tiger Abteilung 502 under the command of Major Willy Jähde.

Recognizing the threat posed by the Soviet incursion, Heeresgruppe Nord diverted other depleted units to the area, including Brig. Gen. Curt Siewert’s 58th, Oberst (Colonel) Hero Breusing’s 122nd, and Maj. Gen. Karl Burdach’s 11th Infantry Divisions. Maj. Gen. Max Horn’s 214th Infantry Division was also ordered to rush to the scene from Norway.

North of Narva, the Russians were able to establish another strong bridgehead at Ssiversti with elements from the 2nd Shock and 47th Armies. To counter this major threat, Brigadeführer (Brig. Gen.) Franz Augsburger’s 20th Waffen-Grenadier-Division, made up of Estonian volunteers, was committed from its training centers directly into the battle. The division arrived in the sector on February 20. Supported by a company of Jähde’s Tigers, which had been diverted from the battle in the south, the Estonians managed to eliminate the bridgehead after nine days of heavy fighting.

While fighting raged in the north, the 8th Army had reinforced its bridgehead south of the city. The added troops were proving too much for the German units facing them, and by February 24 the Russians were on the verge of cutting the railway that was vital to the defense of Narva.

The Germans counterattacked again and again in an effort to stop the Russian drive. Supported by Jähde’s Tigers, the 61st and Feldherrnhalle Divisions finally got the upper hand. Once again, Leutnant Carius was in the thick of things, eliminating several Soviet tanks and helping the infantry clean out Russian defensive positions. The Russians finally pulled back, but Narva’s defenses were weakened as the Nordland’s Regiment Norge was pulled from the city and sent to reinforce the German lines in the south.

With his attacks north and south of the city proving unsuccessful, Govorov decided to focus his attacks on the eastern bank bridgehead. His first assault was aimed at Nederland’s 49th SS Regiment De Ruyter (DR), dug in around Lillienbach. Commanded by Obersturmbannführer (Major) Hans Collani, the regiment was subject to an intense artillery barrage, which was lifted only when the first Soviet troops were within grenade distance of the defenders’ trenches.

Collani’s Dutch volunteers rose from their foxholes and sent a deadly hail of fire into the advancing Russians, but the Soviets pressed on regardless of losses. Frenzied hand-to-hand combat took place in the trenches, while Collani called for covering fire from Schlütter’s artillery, which devastated the second and third waves of the attack. It took hours of vicious combat before the Dutch were able to clear their trenches.

Licking their wounds, the Soviets spent the next few weeks pummeling Collani’s lines with artillery. It was dangerous for the Dutch to even raise their heads above the trench line, but work continued on strengthening the line, with Nederland’s engineers taking several casualties from shellfire as they laid heavy strands of barbed wire in front of their positions.

Reinforcements flowed forward to Govorov’s divisions during the first days of March. The Red Air Force also became extremely active, strafing German positions at will while the Landser (common German soldier) looked in vain for Luftwaffe support. A large wave of Soviet bombers hit Narva on the night of March 6-7, followed by a huge artillery bombardment that all but obliterated any buildings left standing by the bombing. Narva’s civilians fled the city, which resembled a ghost town after the Russian attack.

Govorov then switched the axis of his attack by hitting von Westphalen’s Danmark Regiment, guarding the southern flank of the bridgehead, and Nederland’s SS Panzergrenadier Regiment 48 General Seyffardt (GS), commanded by Standartenführer (Colonel) Wolfgang Jörchel. Von Westphalen’s men held the line, but Jörchel’s troops were forced out of their positions by the Soviets. Gathering staff personnel, cooks, drivers, and other rear area troops, Jörchel led a counterattack that drove back the Russians. Suffering heavy losses, the Dutch troops finally reoccupied their trenches.

Stymied by his failure in the center, Govorov switched back to Collani’s sector around Lillienbach. Following an intense artillery barrage, the Soviets hit hard with infantry and tanks. Assault troops stormed the Dutch positions, breaking through in several areas. With the help of Jähde’s Tigers and artillery fire from the west bank, the Russians were stopped in some sectors, but Govorov funneled more infantry and tanks into the breaches, forcing Collani’s men back.

The situation became even more critical for the Germans when a column of Soviet tanks broke off from the main engagement and headed south to take the Narva River bridges. Steiner realized that enemy seizure of the bridges would doom the bridgehead and sent for Kausch’s HvS to stop the Soviet drive. The panzers arrived ahead of the Russians and met them head on, destroying several T-34s and forcing the rest to retreat.

Kausch followed the enemy north but was stopped in his tracks when he ran into several more Russian tanks that had been dug in to meet his attack. After losing several of his own vehicles, Kausch withdrew and formed his own defensive line. For the time being, the Narva bridges were saved.

Meanwhile, the situation around Lillienbach had grown even more critical. DR had suffered heavy casualties, with some companies at 50 percent strength or less. Collani knew that if the Russians hit him again with an all-out assault, there would be no stopping them. He made preparations to shorten the line by withdrawing to secondary positions to his south, but the Soviets beat him to the punch.

In the early hours of March 14, the Russians attacked after a short preliminary barrage. As the surprised SS crouched in their trenches, the Soviet infantry moved forward and reached the Dutch lines just as the barrage lifted. With cries of “Urra,” the Red Army soldiers stormed the trenches, catching Collani’s men off guard. The German commander ordered a general retreat toward the lines to the south, but the damage had already been done. In the cold, black night, Soviet troops rushed forward, hoping to cut off and destroy the retreating SS before they could take up new positions.

While some of Collani’s units retreated in panic, others continued to fight an orderly withdrawal. Untersturmführer (2nd Lt.) Helmut Scholz, commander of the 7th Company, described his actions in a letter to the author; “As soon as Ivan started shelling us, I knew something was up. Although we had suffered several casualties, I formed up the survivors and launched a counterattack against the Russians that were infiltrating around us. It was pure necessity. As SS, we knew that there was very little likelihood that we would be taken prisoner by the Soviets.”

Scholze and his men met the enemy in the trenches, fighting desperately with any weapon available. Combatants stabbed at each other, shot at close range, and even used their bare hands to kill. It was a brutal fight, but the Russians were finally forced back, leaving behind many dead and wounded.

Russian units still managed to penetrate the area around Lillienbach, surrounding Shcholz’s battalion, commanded by Hauptsturmführer (Captain) Karl-Heinz Ertel. Ordered to execute a fighting withdrawal, Ertel’s men hastily formed up and headed off into the darkness. The Russians struck the battalion again and again, coming out of nowhere and disappearing into the night after inflicting more casualties on the beleaguered unit as it made its way through the forest.

Ertel ordered Scholz to take his company and open a corridor through the surrounding Soviets. His men formed a wedge and advanced, firing at anything that moved. The Russians were overcome by the ferocity of Scholz’s attack, and a corridor was opened for the rest of the battalion to pass through. Calling in artillery fire to keep the Soviets at bay, Ertel and his men finally reached their new positions. Scholz and Ertel were both awarded the Knight’s Cross for their actions.

As bad as it was for the Germans, Govorov’s men had suffered more in casualties and equipment. He called a one-week halt to operations to beef up his divisions, but the Soviet general knew that time was running out. The spring thaw was approaching, which meant almost impassible terrain would soon become the norm. The mud would make the movement of armor and heavy vehicles all but impossible, so Govorov made one last attempt to break the German line before the thaw set in.

On March 22, tons of Russian explosives rained down upon the DR positions. A wave of Soviet infantry hit the 5th Company with a vengeance, threatening a breakthrough that would split the II Battalion. Hauptsturmführer (Captain) Carl-Heinz Frühauf, who had just replaced Ertel as the unit commander, rushed to the scene with a hastily formed assault unit made up of headquarters and supply personnel.

Frühauf and his men ran headlong into a Soviet assault force of about 150 men. It was man-to-man combat as the two sides clashed. For more than half an hour, men slashed at each other with bayonets, struck savage blows with sharpened entrenching tools, and tried to choke the life out of their opponents.

The Russian force was wiped out, and Frühauf pushed his men forward once again. Gathering stragglers from the 5th Company, the SS managed to retake their lost positions and fire a final volley at the retreating Soviets before slumping in exhaustion to the bottom of their trenches.

Southwest of Narva, the Soviets kept up the pressure on the remnants of several German divisions. The Germans held a stretch of land pointed like a dagger in the Russian lines. On either side of the salient, Soviet troops battled tirelessly to break through the German defenses and sever the main supply highway and rail line that ran from Wesenberg to Narva. The Germans nicknamed the two Russian-held sectors the Ostsack and the Westsack.

It was a game of attack and counterattack, followed by heavy artillery bombardment, low level bombing, and strafing from both air forces. Men fought and died for a small stretch of land that had a moonlike quality about it because of the constant shelling. The Germans held—barely, thanks to the support of Jähde’s Tigers, which roamed the battlefield in search of enemy armor.

“Ivan didn’t grant us any rest,” Leutnant Carius wrote. “He wanted to roll up or encircle the bridgehead at all costs….[In one action] we knocked out six T-34s and a T-60 and destroyed a 76.2 mm AT [anti-tank] gun.”

The Russians made one final attempt to break the German line in the Ostsack on March 22. Once again the Tigers rolled into action, blasting enemy armor in support of the German infantry. The Soviets finally gave up, and the sector went into a relative state of quiet. During the period March 17–22, the Tigers had knocked out a total of 38 Soviet tanks, four assault guns, and 17 artillery pieces at the cost of one wounded panzer crewman.

It was the Landser that suffered the most during those battles. An after-action strength report in late March put the I/399th Regiment of the 170th Infantry Division at 69 combat effectives, which was just about the strength of half a company.

While the Russians were held in the southwest, another problem was taken care of around Sergala. Russian forces occupied the vital communications area, located several kilometers to the rear of Narva, and the weak German opposition could barely hold them in check. In late March, Regiment Norge began an attack to reclaim the area. After heavy fighting, the Soviet forces were destroyed, and German units reoccupied their old positions. The regiment was then ordered back to the Narva line to act as support for the bridgehead.

In early April, the spring thaw hit with a vengeance, ending most offensive operations. Throughout the month, both sides strove to regain their strength. More Soviet reinforcements and replacements arrived to fill in the gaps left by the previous month’s attacks. Red Air Force bombers and ground attack aircraft lashed out again and again on anything that moved on the German side, while Red Army artillery zeroed in the Narva line and the eastern bridgehead.

Casualties inside the bridgehead were common, as engineers braved Russian fire to work in the open, laying mines and strengthening waterlogged positions. A prime Soviet target was the bridge supplying the bridgehead. It was damaged several times by artillery fire and bombs, but the engineers worked unflinchingly to keep it standing. The infantry worked side by side with the engineers and suffered many casualties, among them, the commander of Regiment Danmark, Obersturmbannführer (Lt. Col.) von Westphalen.

“We worked like madmen to strengthen our positions,” Unterstrumführer (2nd Lt.) Scholz wrote to the author. “At higher headquarters, they call this period a lull, but we took casualties on a regular basis from artillery and snipers. Still, we knew that this work had to be done—the strengthening of bunkers and the reinforcement of outposts.”

On the western bank of the river, Sturmbannführer (Major) Schlütter had the same opinion about the so-called lull in the fighting. “We knew that we [the artillery] were the backbone of the bridgehead’s defense,” he wrote. “Our Nederland artillery and the Nordland’s artillery were called upon to break up many a Russian attack. At the same time, we had to constantly move our positions because of Russian counter-fire and air attacks. This was exceedingly difficult when the thaw began. We often had to drag our guns through knee-deep mud, at the same time watching out for snipers, Russian aircraft, and dodging artillery fire.”

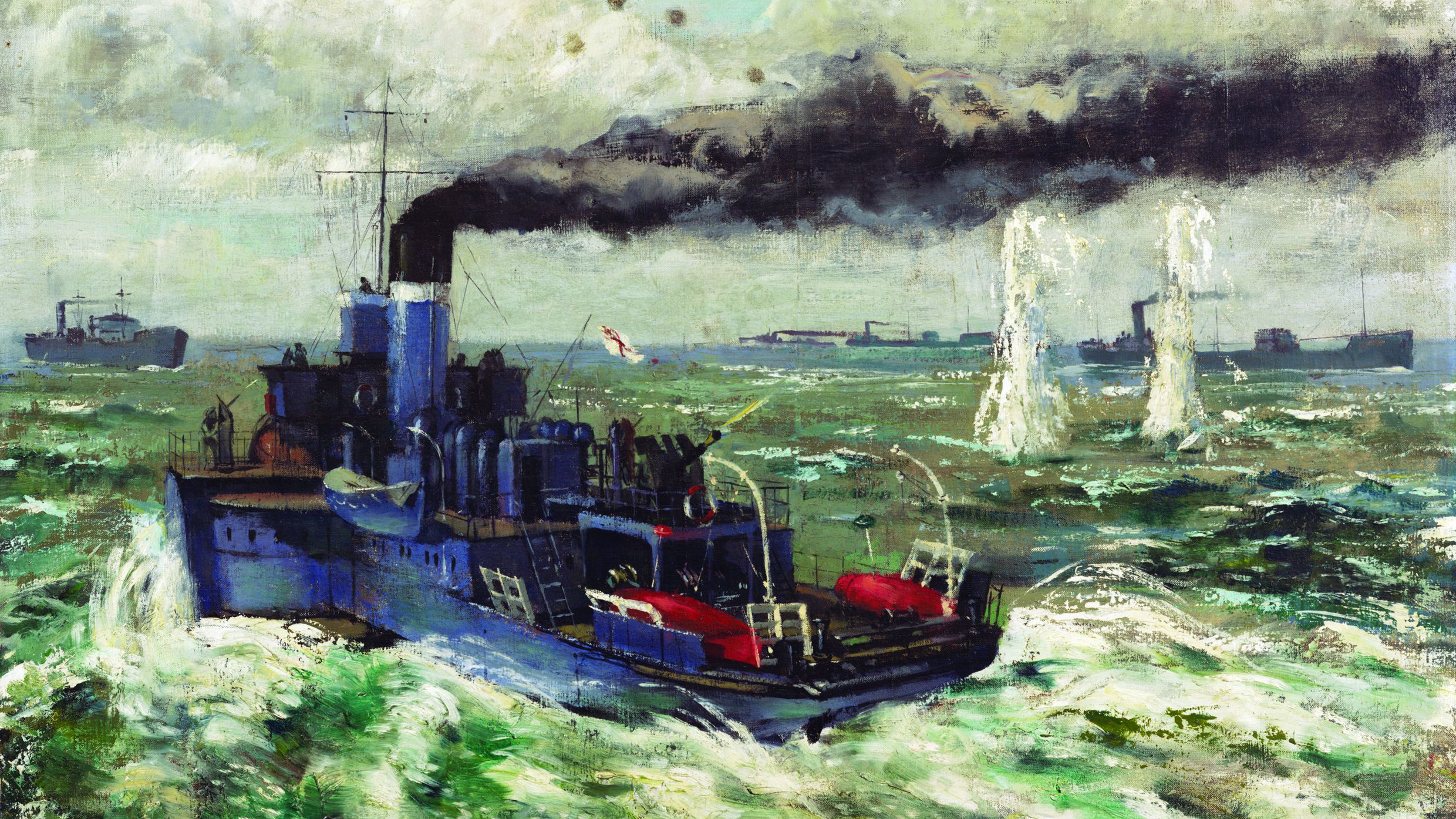

Frustrated in his attempts to smash the enemy bridgehead, Govorov tried an end run with an amphibious landing behind the German lines on the Gulf of Finland coastline. The landing caused a momentary panic, but a swift response by local coastal and SS alarm units smashed the Soviet landing units before much harm was done.

Moscow was getting impatient at the lack of progress on the Narva Front, and Govorov was feeling the heat. As the ground began to dry out, he ordered several heavy attacks to be launched against the Lillienbach area. Machine guns mowed down wave after wave of the attacking Russians, but more followed, closing to fight a savage hand-to-hand battle with the men of Nederland.

The Dutch were able to hold, so Govorov switched his focus to the Danmark sector in the south. Under cover of heavy artillery and air support, the Soviets surged toward the German lines. They attacked fearlessly, disregarding their frightful losses, but it was all in vain. Once again, Govorov was forced to order a cessation of the attack so that his men could rest and receive replacements for the terrible casualties they had incurred.

While the Red Army rested, the Red Air Force went into action over the front. To the SS men below, the sky seemed filled with Soviet aircraft. Narva was pummeled into ruins, with hardly a building left standing. The bridgehead was also heavily hit, making the already lunar-like landscape even more grotesque.

The air attacks went on for days while Govorov marshaled his men for a new attack. Once again, he picked Lillienbach as the focus for his new assault. This time, the German and Dutch defenders were forced to give way, having had their ranks severely depleted by the intense bombing and the fighting of the previous weeks.

Von Scholze ordered the men in the Lillienbach sector to make a fighting withdrawal, and they slowly retreated to new positions closer to the river. The Russians followed, only to be stopped in their tracks by the guns of Schlütter’s artillery. Although the Soviets had gained ground, they still could not make the decisive breakthrough that Govorov hoped for.

In Moscow, Stalin and his STAVKA had turned their attention away from Narva and were devising a plan, Bagration, that they hoped would drive the Germans out of the Motherland and bring the war to the gates of Berlin. With a remarkable display of stealth and deception, 19 Soviet armies were moved into position to strike at Heeresgruppe Mitte, the army group just south of Heeresgruppe Nord. The attack was set to begin on June 22, just three years to the day that the Wehrmacht had invaded the Soviet Union.

To keep the Germans off guard, Moscow ordered Govorov to continue his assault against the Narva line. The muddy season had come and gone, and Govorov’s divisions had been replenished with men and materiel. Ammunition was replenished, and Red Army mechanics had seen to it that the Soviet armor would be in good running order.

In the attempt to focus German attention away from Heeresgruppe Mitte, STAVKA ordered Govorov to begin his attack on the Narva line on June 7. The southern sector of the bridgehead was the first to feel the ferocity of the Soviet assault when Red Air Force fighters and bombers from the 9th Air Army blasted the German line. Men were buried alive in their trenches or gunned down while trying to escape the brutal attack. Red Army artillery joined the crescendo of death, causing more casualties among the Germans and Danes defending the line.

Dolgaya Niva was particularly hard hit. As the artillery fire lifted, the dazed survivors struggled to rescue wounded comrades or clear weapons that had been clogged by the dirt and debris left by the bombardment. There was precious little time to do either. Looking over the tops of their trenches, the Danes saw masses of Russian infantry approaching on the run.

As the alarm spread up and down the line, the lightly wounded troops picked up weapons to join their unscathed comrades on the line, while those with more severe wounds tried to find a safe haven in which to wait for the medics. At first, the attacking Soviets were met by a smattering of gunfire, but before they had reached the trenches, the entire line had come alive.

Luckily, some of the communication lines were still working. A request for artillery support was answered almost immediately, and the guns of Nordland’s artillery regiment began to wreak havoc on the attackers. Artillery observers called in fire directly in front of the trenches, and the first wave of Soviets was obliterated. A second wave, and then a third, met the same fate.

The Russians attacked again and again during the next few days but achieved little for their efforts until June 12, when a breach of the main German defense line was made. Soviet forces surged through the gap, widening it as new units were rushed to the scene. The order was given for the Danes to pull back to new lines closer to the river, where both Nordland’s and Nederland’s artillery could support them.

The withdrawal took the Soviets by surprise, and they paused to reform their units before making an all out effort to take the main Narva bridge. Seeing the Russians hesitate, 26-year-old Unterscharführer (Sergeant) Egon Christopherson, a squad leader in Danmark’s 7th Company, formed an assault group from his own men and surrounding units. “We have to hit them hard and fast,” he told his men. “When we charge, yell like the devil himself.”

Christopherson’s men struck the Russian flank, spraying the surprised Soviets with gunfire and hurling grenades into their midst. Some of the Russians returned fire only to be gunned down by the seemingly berserk SS men. Panic seized the Soviets, many of whom were new replacements. Some threw down their weapons to surrender, while most began a hasty withdrawal. The sight of their comrades retreating threw other units into disarray, and Christopherson’s men surged forward to retake their lost trenches.

Other units followed, until the entire line was once again in German hands. For his actions, Christopherson became the first Dane to be awarded the Knight’s Cross. His actions had saved the day, but the losses suffered by Danmark had been frightfully high. At Corps headquarters, Steiner reviewed the day’s events and looked over casualty reports. He realized that the days of the bridgehead were numbered, and he ordered engineers to begin the construction of a new defensive line.

Codenamed Tannenberg, the line would be the fall-back point once the Russians had crossed the Narva. The new defenses would be located a few miles west of the city and would incorporate existing natural obstacles in its overall construction. Although he had instructed his engineer commander to work day and night to complete the position, Steiner knew that the men inside the bridgehead would have to suffer even greater casualties before the new line was finished.

Throughout June, Govorov kept hammering the bridgehead with artillery and air attacks, followed by combined tank and infantry assaults looking for the key to cracking the German defenses. The landscape had been churned up so much in the past few months’ fighting that it was virtually impossible to distinguish any reference points on maps made less than a year ago. Grisly reminders of past battles were everywhere, with body parts, half buried in the plowed up ground, strewn in front of the trench line.

The units inside the bridgehead had received little in the way of replacements, and alarm platoons had to be set up behind the main positions, ready to move at a moment’s notice to counter any enemy threat on the thinly held line. Inside Narva itself, Sturmbannführer (Major) Schlütter had taken up residence in the partially damaged city courthouse and had set up an observation post in one of the building’s turrets.

“We had a fairly clear view of the battlefield,” he wrote to the author. “Besides having observers on the front line, we could see possible trouble spots from the tower. This allowed us to sometimes direct artillery fire on enemy assault units without going through the observers in the field. Where seconds could mean lives, this was a great help to the men defending the bridgehead.”

Govorov had enough troops to keep the Germans off guard, moving his attacks from one sector of the bridgehead to another. Although the terrain was mainly unfit for armored movement, the Russians continued to push tanks into the area. Jähde and Kausch had been ordered north of the city to help German and Estonian units battle yet another Soviet attempt to establish a strong bridgehead on the west bank of the Narva.

The absence of German armor meant Nederland and Danmark had to rely on their own tank-killer squads. Engineer units could engage the armored monsters with flamethrowers, but the infantry was forced to improvise with “sticky” mines or bundles of grenades. It was deadly work, running alongside a T-34, trying to lodge a bundle of grenades in the drive wheels of the tracks or actually mounting the tank to attach a mine to the turret ring. Those who succeeded then had to jump away and hope that the ensuing blast did not kill them when the tank blew up. Those that failed usually died screaming under the treads of their intended victim.

On June 22, the Red storm broke against the divisions of Heeresgruppe Mitte. Soviet artillery regiments sent thousands of shells crashing into the German defenses, while the Red Air Force unleashed an all-out campaign from the sky. A well-coordinated armor and infantry assault tore gaping holes in the German lines and reinforcements were rushed forward to expand them.

Frantic calls for help came from divisional headquarters, but there were no reserves to be found. At Vitebsk, five German divisions were surrounded and destroyed during the onslaught, which continued for several days. Some divisions merely melted away as the Soviets advanced. Others found themselves surrounded deep behind enemy lines with little hope of rescue, and the dark specter of defeat loomed over higher headquarters as the lines buckled and then collapsed.

Steiner read the grim reports of the looming disaster to his south while his men fought off repeated assaults at the bridgehead. The Soviets at Narva were also aware of the tremendous gains made by their comrades, and their morale soared as reports of new victories were read to them by their commissars.

Govorov decided that the time was ripe for a new all-out assault on the bridgehead, and by mid-July the Soviet general had assembled about 20 divisions to destroy Steiner’s corps and the depleted German units on his southern flank. Several new bridgeheads were thrown across the Narva River, and German reconnaissance reported that a massive buildup was in progress.

Berlin would still not let loose of the idea of holding the bridgehead, but Steiner knew that once Govorov’s attack began his men would have no chance of survival. Taking matters into his own hands, Steiner ordered the units inside the bridgehead to prepare for evacuation. In small groups, the men of Danmark and Nederland began to filter back to the river. Dummy gun positions were constructed, and night fires were lit in trenches to give the illusion that the lines were still decently manned.

On the western shore, Sturmbannführer (Major) Schlütter received orders to cover his retreating comrades with artillery fire, if necessary. “We knew that the big move was underway,” he later wrote. “I laid out coordinates for every possible move that Ivan might make. At the same time, I drew up plans for our own withdrawal. We were ordered to hold our positions until the last troops had come out of the bridgehead. Then, we were to cover the engineers charged with blowing the bridges.”

Several groups had already made their way out of the bridgehead by July 23, when Govorov’s reconnaissance finally recognized what was happening. Hoping to catch the Germans flat-footed, he ordered a general attack throughout the sector. Soviet forces in the bridgeheads established on the west bank lashed out, driving the Estonian SS troops westward. South of the city, reinforced armored and infantry units broke the German line and headed toward the Tallinin Highway with little more than token enemy forces in front of them.

The evacuation of the bridgehead continued, with Schlütter’s guns blasting away at the advancing Soviets. Overhead, more than 800 Red Air Force aircraft fought with the remnants of Luftflotte I, which had only 137 planes to oppose them. Surprisingly, the bridgehead forces retreated in good order, making their way across the bridges as Schlütter watched from the burned-out courthouse.

“As the final troops crossed the bridges, we could see the Soviets following quickly on their heels,” he wrote. “Suddenly, my own position came under artillery fire, starting what was left of the courthouse on fire. I gave the order to my radioman to tell the engineers to blow the bridges without delay. We were coming down the steps, with burning timbers falling all around us, when we heard the massive explosions. The engineers had blown the bridges with only minutes to spare.”

With his mission completed, Schlütter saw to his own men’s safety. His preplanned evacuation route lay open to the west, and the guns were already being prepared for movement. “We hitched the horses to the artillery and made our way out of the city,” he wrote. “No one knew what lay ahead of us, but the hell of Narva was behind us. Little did we know that we had almost another year of war to fight. Little did we know how many more of our comrades would fall before the last bullet was fired.”

Pat McTaggart is an expert on World War II on the Eastern Front and the author of the forthcoming book Siege! about six epic sieges during the war in that theater. He resides in Elkader, Iowa.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments