by William McPeak

Although formal training in the use of the pike—an ash-handled spear 18 to 20 feet long—did not begin until the 15th century, ancient Greeks and Romans used so-called “long spears” as standard infantry issue against cavalry. A long spear was also used by Saxon warriors from about 400 to 700 ad, “long” in this case also referring to the spear tip and socket, which were twice the length of a standard spear. Medieval knights wielded lances 12 feet long, which also inspired contemporary weapon-makers to design longer spears for infantry. In 1297, Scottish rebel leader William Wallace anticipated the modern pike when he armed his men with branch-stripped and sharpened saplings to use against the English heavy cavalry at the Battle of Stirling. A century later, Swiss soldiers used 10-foot-long spears to good effect against Austrian armored cavalry at the Battle of Sempach. By this time, the mounted knight was already shying away from direct encounters with the rapidly expanding variety of wicked polearms, including the glaive and the billhook, which rendered his horse particularly vulnerable.

Burgundian, Italian, and Swiss mercenaries had begun populating European battlefields more and more frequently in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. With their growing expertise, they had progressively become necessary players in warfare. Added to the mercenaries’ expert handling of such contemporary weapons as the crossbow and the longbow was their use of the matchlock shoulder firearm, or arquebus. This was a weapon of great potential, but it was only effective when properly protected behind a defensive entrenchment or with supporting bowmen or spearmen, themselves in need of flanking cavalry for defensive support. None of these would risk facing heavy cavalry in the open field without some form of massed defense. The invention of the pike greatly simplified the European military equation. By the late 15th century, the basic pike was a crucial weapon in the hands of the mercenaries.

Pikemen: History’s Resolute and Versatile Warriors

Swiss mercenaries, already well noted for their skill as specialized infantry utilizing other polearms, began taking to the field in the mid-1400s with 14- to 18-foot-long pikes comprised of ash poles fitted with leaf- or diamond-pointed steel heads. With their prior training with extra-long spears, the Swiss handled the seemingly unwieldy new polearm with surprising dexterity and speed. They used the pikes in rank-and-file formations made up of companies called “bands.” The result was nothing less than a portable palisade ideally suited for both defensive and offensive actions in the open field. Resolute pikemen, drawn into a close square and presenting ground spikes—the butts pressed against and perpendicular to the foot—at a low angle in the front rank and horizontally in progressively deeper ranks, could turn aside charging heavy cavalry without the need of other support. And if the cavalry persisted in riding upon them, they were fully capable of taking the offensive and defeating the horsemen by themselves.

The canton bands of the Swiss Confederation demonstrated the power of the pike often on their way to becoming the most sought-after mercenaries in Europe in the late 15th century. Their chief employer was the king of France, and when King Charles VIII was ready to invade Italy in 1494 in the Hapsburg-Valois Wars (also known as the Italian Wars), the Swiss had already become integral to the employment of French infantry. By then, the Swiss were almost exclusively pikemen, having pared down the number of aquebusiers, archers, and hand cannoneers. They wore little armor: an open-faced helmet (sallet), a thick dagger (later copied by the Nazis as the SS dagger), and a short, straight, saber-like sword called a Schweizerdegen. They wore multi-colored hose and doublets, either yellow-red or black-white, with the white cross of the Swiss Confederation on the front. Once on the battlefield, they had a habit of kissing the ground as a sign of humility—but that was as far as their humility went. After a battle had started, they were fierce and pitiless fighters.

The Swiss were a major force in French military victories until 1503, when a series of defeats characterized the next two decades. At Cerignola, they were defeated when their brashness led them to run upon Italians firing arquebuses from a raised road embankment. At Marignano in 1515, they fought against their usual paymaster, the king of France, in a titanic battle of wills lasting two days in which the cavalry-oriented King Francis I was able to best the pikemen with flanking maneuvers. The Swiss had not yet learned their lesson in undertaking reckless frontal assaults. In 1522 at Bicocca, they seemed at long last to get the point. Again in the employ of the French, they charged up an embankment, only to drop into a ditch on the other side, where they were trapped and decimated by imperial Spanish arquebusiers as they desperately tried to scale the opposite earthen rampart. The French lost so many officers that they never again committed to the Swiss pike to win engagements during the Italian Wars.

How Pikemen Companies Were Formed National Armies

By no means were the Swiss the only pikemen in the field at the time. The pike hedge was a popular new intimidating force on the battlefield. The Spanish, already premier arquebusiers, used crack pike units by the beginning of the 16th century. Spanish commanders had modified the bulky three-part medieval army formation into the “tercio,” blending a better proportion of arquebusiers to pikemen in diamond-shaped formations. From the four corners of these arrays, the arquebusiers would fire a volley, then retreat into the center of the pike formation to reload.

Several Italian states, particularly Venice, also fielded well-trained pike companies. But the most notable pike companies besides the Swiss were the Germans, organized in the late 15th century by the Hapsburg emperor Maximilian I, who so respected the Swiss pikemen that he copied them obsessively.

The German pike companies were the Landsknechts, or territorial troops, of the Holy Roman Empire. They carried the lange spiesse—long spear—and were recruited by noblemen who became the company captains or colonels. The German companies were better proportioned with arquebuses than the Swiss, but they were as brash in the field and prided themselves in similar fierceness, reflected in their showy uniforms: large, flat caps topped with ostrich feathers, doublets with billowing sleeves, and short trunks and breeches, called “Devil breeches.” They also carried distinctive side weapons: unique daggers with thin, stiletto-like blades and short double-edged broadswords, called katzbalger, or “cat gutter,” with figure-eight or S-shaped crossguards.

The rivalry between the Germans and the Swiss, who did not cherish the notion of being copied, often grew deadly. Their initial opportunity to cross swords, as it were, occurred during the short 1499 war that Maximilian started over disputed territory in eastern Switzerland. That year, the more seasoned Swiss pikemen gave painful lessons to their German counterparts in a series of small but bloody battles, particularly at Dornach. After that, no quarter was given or taken on either side when the Teutonic cousins clashed in combat. On some occasions, they found themselves fighting on the same side, but the more usual case found them at each other’s throats.

In general battle order, the pikemen of the first ranks were the largest and most skilled. Being out front, they rated some additional armor protection: a breastplate or partial armor to the knee or thigh and an open helmet, often only a small steel cap. The Landsknecht pikemen were accompanied by, the two-handed swordsmen. Although the Swiss had been the innovators of the use of two-handed swordsmen alongside pikemen, by the 15th century they considered the two-handed sword incompatible with the pike, and even outlawed its use in the front ranks of some Swiss cantons. The Germans, by contrast, were outstanding two-handed swordsmen, and those big and strong enough to rate the first rank of a pike company were paid double for their principal work—breaking opponents’ pikes. They too were armored as they went about their business of stepping out before the clash of opposing pikemen and raining haymaker strokes down on the extended enemy pikes to shear off their heads before stepping back to the protection of pikemen in their own companies.

“Push of Pike”

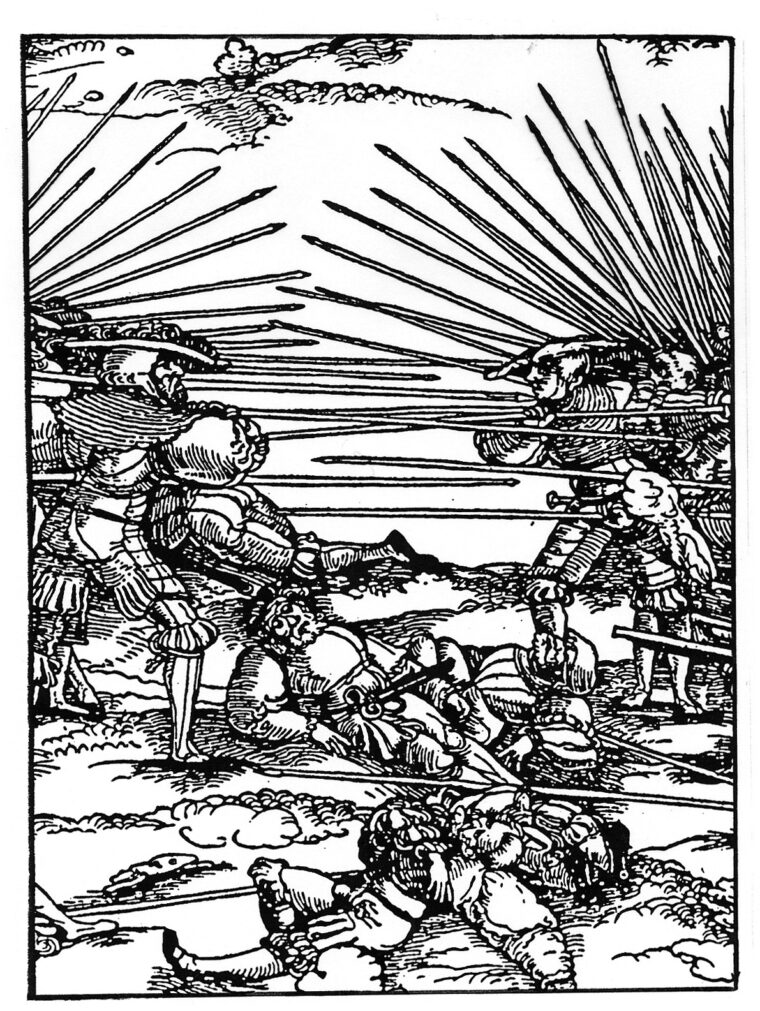

Depending on the outcome of their last meeting, or if there was a particular atrocity to avenge, the clash of Swiss and German pikemen was guaranteed to be explosive. Although cannon and arquebus fire and heavy cavalry charges might cut into their numbers, the face-to-face meeting of the two sides—the “push of pike” as it was known—inevitably would follow. Running upon one another, the two sides would parry pike head to pike head and pike staff to pike staff. With no further room to push and shove, the pikes would be thrown down and swords and daggers drawn for the hand-to-hand melee. The fighting was often so ferocious that whole companies would perish to the man. With loyalty only to their own officers and the pay they received, Landsknecht companies would often meet each other with the same resultant decimation. At the Battle of Pavia, near Milan, in 1525, the fellow Germans fought each other to near extinction, essentially wiping out the original pike companies formed by Maximilian.

Pike formations proved their defensive worth as portable standing palisades, but they did not have to be static. The marching formations of rank and file were versatile enough to be used in more dynamic defenses, as well. Among the many drills that pike units practiced was how to present their weapons for protection while marching. Each side of the pike square could turn to the commanded marching direction and lead the formation into a defensive stance. It was an efficient and disciplined manner of moving off the battlefield in measured retreat instead of mob panic. At the Battle of Ravenna in 1512, several companies of Spanish pikemen were attacked while retreating by French heavy cavalry under the celebrated young general Gaston de Foix. Unfortunately, the brash De Foix unwisely decided that it was dishonorable to let the Spaniards leave in peace. He gave chase with a small mounted contingent. The pikemen turned into a defensive position, and De Foix was unhorsed and killed with many wounds. The Spaniards made good their escape.

Military actions could go awry for any number of reasons, including bad weather. One such weather-related disaster befell the European allies of Spanish Emperor Charles V and his vassals during the attempted siege of Algiers in 1536. A terrific freak storm ruined the otherwise well-coordinated battle plan by wrecking much of the large fleet carrying the besiegers’ siege emplacements. Torrential rain finally forced a retreat, and as usual the Knights of the Order of St. John, a remnant of the old crusading brotherhoods, formed the rear guard. On this occasion they carried both the full pike and a favorite modification, the half pike, a more versatile 8- to 10-foot version of the weapon. As they were being dogged by Moslem corsairs, the knights stopped and presented the full pikes on the perimeter to keep the enemy at bay, while the inner ranks made short charges using the half pikes to drive back the corsairs. Similarly, a botched raid by the Knights on African Zoara in 1552 found the 1,500-man party surprised by a 4,000-man force of mounted Turkish arquebusiers. Knights commander Leone Strozzi ordered his men into a tight square with pikes extended. his own arquebusiers charged from the center to fire and retreat as the formation fell back toward the harbor and the waiting ships. The maneuver was successfully completed with a much lower loss of life than might have been suffered by the raiders.

Many Uses For the Creative Tactician…

A simple but brilliant application of the pike was its use as a handy portable repair for defensive walls shattered by besieging cannons—a bristling plug to fill the breech. An early example of this application was the Spanish defense of the small fortress of Canosa by 1,200 soldiers in 1502 during the second French invasion of Italy. After four days of French cannonading, a 100-foot-wide breech was opened in the fortress wall. The French came on. The hole was quickly shored up by a pike hedge led by Spanish commander Pedro de Peralta, who exhorted those who wavered: “Back, you swine. Back, you craven blackguards. Stand firm!” A three-hour stalemate finally sent the French and their Swiss pikemen into retreat. Here, as in other cases, the pike inspired makeshift applications, with the points being fitted with knobs of burning sulfur that inflicted horrible burns on the French attackers.

The Knights of St. John provided another outstanding example of the use of pikes for fortification repair during the Turkish siege of the island of Rhodes in 1522. Fielding only 5,000 men to the 200,000 attackers under the great sultan Suleiman, the Knights had contracted with Spanish and German pikemen. The Turks unleashed a brutal and unprecedented bombardment and mining effort that lasted all summer. In the fall, they mounted attempt after attempt to storm the now rubble-strewn walls of the island. Time and again they were thrown back by the defenders’ massed pikemen, who were shuttled wherever they were needed most. During the most intense attempts, the Knights used half pikes to drive off the Turks. Eventually, the sultan offered a conditional surrender, which the Knights accepted.

As firearms grew in greater efficiency and variety in the 16th century, pike formations also grew in size and sophistication. Armored cavalrymen took up firearms as well to regenerate their dominating influence on the battlefield. Throughout the period, pikemen combined with infantry in regiment-sized units to combat multiple companies of armed cavalry. The reality of a more uncertain battlefield induced pikemen to wear standard helmets and half armor along with swords and daggers. Eventually, however, the pike saw its sun set as a prime military weapon. By 1650, it was losing tactical worth, giving way to a general tendency toward greater battlefield speed and disappearance of armor. By the late 17th century, the plug bayonet completed the integration of firearm and polearm into one weapon, spelling the end of the pike, surely the most versatile polearm in the annals of warfare.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments