By Eric Niderost

The citizens of Vicksburg would scarcely remember a more beautiful evening. The sky on April 16, 1863, was cloudless, and as the ruddy glow of twilight faded, the vast expanse was speckled with stars. The city was perched on high bluffs above the mighty Mississippi River, just below a place where the father of waters bent back on itself. It was the time of a new moon, and therefore much the surrounding countryside was shrouded in darkness. Vicksburg citizens knew that somewhere out there in the inky void Union land and naval forces were hovering. But the Northerners had tried to take the city for a year. All they received for their trouble were 12 months of aborted attacks and frustrated hopes.

In peacetime Vicksburg was a prosperous town of some 4,500 souls. In war it assumed a strategic importance far beyond its population figures. If the Mississippi River was, in Lincoln’s phrase, the “backbone of the rebellion,” then Vicksburg was its guardian. It was also a railroad hub where men and supplies from the western Confederacy were funneled through to the east.

The Federals had already taken New Orleans in April 1862 and were working their way north, while Grant’s forces were moving south down the mighty river. Once Vicksburg was taken, the entire length of the river would be under Union control, and the Confederacy would be divided in two. The capture of Vicksburg was an essential ingredient in the North’s plans to subdue the South and restore the Union.

But from late 1862 to the spring of 1863 Federal efforts were cursed by failure. In December 1862 an attack led by Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman proved abortive. It seemed that all Union plans were plagued by ill luck. However, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and his Army of the Tennessee were not about to give up so easily.

Grant pinned his hopes on trying to get his 45,000-man army to flank Vicksburg and proceed to the dry and stable ground to the east of the city. A cutoff canal was attempted, a project that would essentially bypass Vicksburg and allow the Navy to transport his army south of the beleaguered city. In a second effort, the Lake Providence Canal project begun in February 1863 was a bold effort to connect a labyrinth of bayous and small waterways and create a path into a 400-mile circuitous route past Vicksburg.

These efforts proved abortive because mud reigned supreme. Bluecoats traded rifle muskets for spades, dredging up tons of the viscous muck, but rains flooded the excavations and drowned their labors as well as their hopes. Disease was also present, and the ranks were thinned by dysentery, pneumonia, typhoid, and the dreaded yellow fever.

Ever probing, joint Union Army and naval forces also tried to break through the swampy, waterlogged territory just north of the city, first at Yazoo Pass, then at Steele’s Bayou. The Union Army had started work on these projects in February 1863 and March 1863, respectively.

The low-lying terrain was a nightmare: 200 miles of bayous thick with trees, crawling with snakes, and riddled with disease. It was said bobcats, snakes, and other swamp creatures would suddenly drop down on gunboats from the overhanging canopy of dense trees, only to be swept off the decks by alert sailors armed only with brooms.

When Confederate infantry threatened to capture Rear Admiral David D. Porter’s naval assets deployed in the struggling Yazoo expedition, it was the last straw. Literally bogged down, Porter asked Sherman for help to drive away the enemy. Sherman obliged, but the whole force turned back. It was another seemingly ignominious failure.

Confident that the Federal forces would never succeed, many Vicksburg townsfolk felt it was time to celebrate their good fortune. A ball was scheduled for the evening of April 16, 1863, at one of the city’s finest mansions. Confederate officers wore their dress uniforms and ladies their finest gowns. The Yankees might be somewhere out there, but they were mere nuisances, no more than buzzing flies at a picnic.

But the Vicksburg celebrations were premature. Grant was about to open a whole new phase of the Vicksburg campaign, brilliant in design and bold in scope. Part of the plan was to run a convoy of transports downstream, but to do so meant running past several miles of Confederate guns that protected the city. It was a calculated risk, but it had to be done if Grant’s plan was to succeed.

Porter readily agreed to Grant’s proposals. Once south of Vicksburg, Porter and his ships would rendezvous with the Army of the Tennessee and shuttle the bluecoats from Louisiana to Mississippi. The heart of the plan was to approach Vicksburg from the east, where dry and firm ground provided stability for artillery and generally favored an attacking army.

Porter, imposing with his full beard and military bearing, was also a keen observer and subtle tactician. There would be about a dozen Federal ships making the downriver attempt, a mixed force of ironclads and transports. The admiral issued orders to pilots and captains that they were to hug the western, Louisiana shore where the thick groves of trees that lined the banks combined with the new moon’s feeble light to cloak their passing.

But if they were discovered, the Federal ships were to proceed with all possible haste to the eastern banks of the Mississippi. This seemed counterintuitive, even suicidal, because that was the Vicksburg side of the great river. Nevertheless, orders were orders, so Porter’s subordinates were going to follow his commands. But there was method to his madness. The admiral had observed something in previous gun duels with the Confederate batteries. Still, it was a gamble.

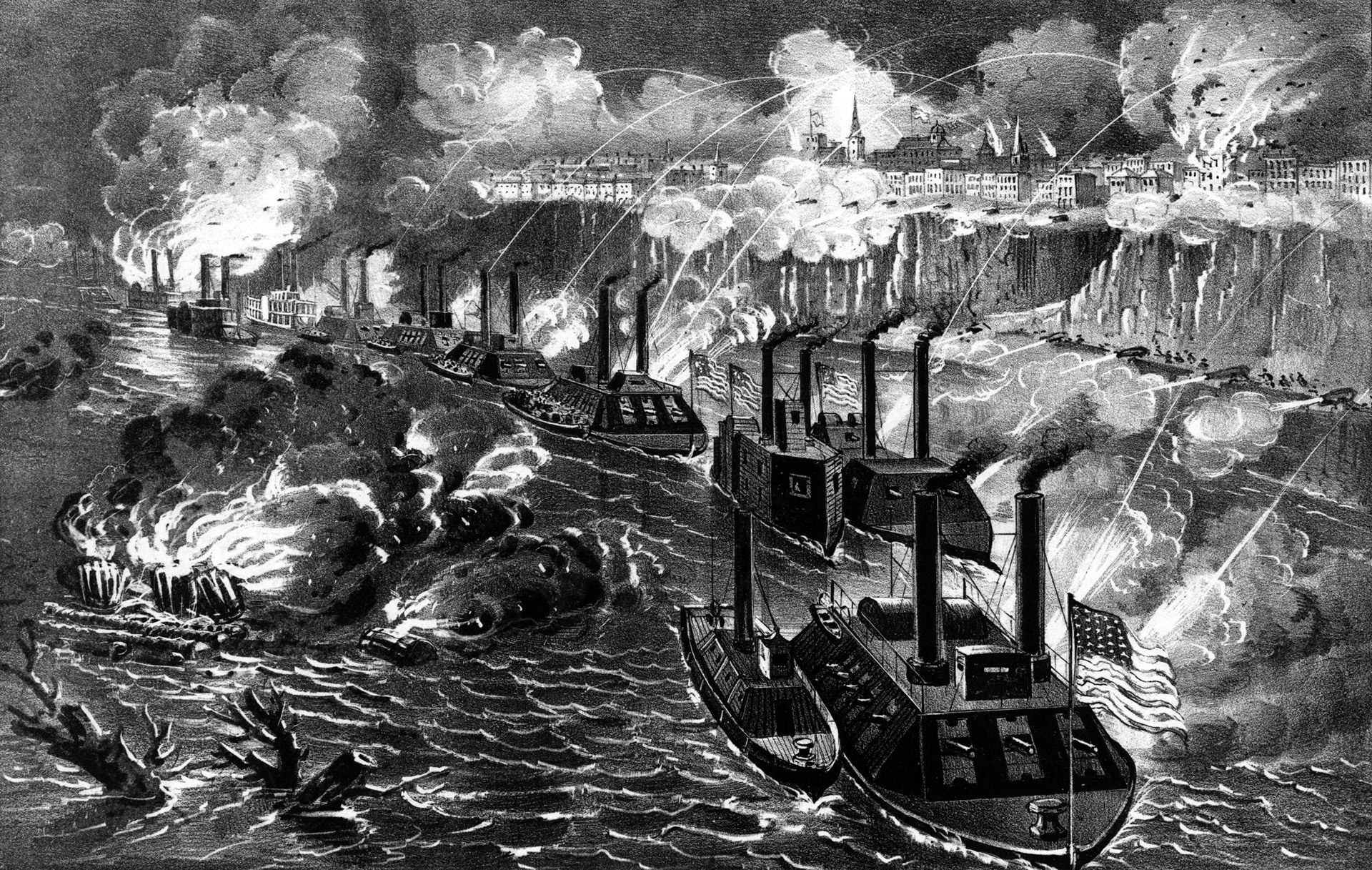

It was about 10 pm when the Union convoy rounded the point, Porter’s flagship, the Benton, in the lead. At first all was well, but then Confederate spotters saw the Federal ships in the inky void and raised the alarm. Sentries fired signal cannon, their reports the first notes in the symphony of artillery fire.

Suddenly small flames shot up in one place, then another and another. These were from barrels of tar and pitch placed at intervals to provide light for emergencies like these. Cotton bales soaked in oil were also set ablaze. As if that were not enough, small sheds and warehouses that lined the levee were put to the torch. The flames cracked and danced, combining with the blazing cotton bales and tar barrels to produce a lurid but ever brightening glow that illuminated the Mississippi for at least a mile.

The Federal ships could be seen clearly now, seemingly perfect targets for the 30-odd guns that lined Vicksburg’s riverfront defenses. These cannons sprang to malevolent life with ear-splitting roars. Union ironclads fired in counterbattery, the whole scene dissolving into confusion and chaos. Shells rained down to detonate in lethal bursts of metal, smoke, and flame.

The Federal ships began to maneuver toward the Vicksburg shore, seemingly to within pointblank range of the Confederate batteries. But Porter’s observations were correct: for the most part the Confederate guns, mostly situated in high bluffs, could not be depressed low enough if the Union ships came too close. The upper works of the ships might be smashed to kindling, but they were still unscathed otherwise.

Ironically, the grand Vicksburg ball also unwittingly played into Union hands. Many of the artillery officers were attending the festivities, and it took time amid all the noise and confusion to report back to their posts. Yet the river seemed to be on the South’s side that night. The Mississippi River was treacherous at the best of times, and currents and eddies threw some Union ships off course. A few were even grounded but managed to free themselves under heavy fire.

The Lafayette had the misfortune to run aground right in front of a Confederate battery. The rebels did manage to depress their guns enough in this sector to do Lafayette some serious damage. Nevertheless, though the crippled ship received nine direct hits, she freed herself and continued on. Only one coal transport, the Henry Clay, caught fire and was lost.

It was a spectacular success. All ships save the Henry Clay had made it though. Porter’s casualties were also light, with no dead and only 12 wounded.

Pleased with this success, Porter ordered another run a few days later. The April 22 attempt was not as lucky; six barges were sunk out of the dozen that were being towed down the river. Still, the operation was enough of a success for Grant to begin the boldest and riskiest part of his plan. The first step was to have his army cross the great river to the Mississippi side, which was no small undertaking, especially if there was Confederate opposition on the eastern shore.

The Army of the Tennessee marched down to a spot some 35 miles south of Vicksburg and ferried across the Mississippi to the high ground at Bruinsburg. Grant’s troops were no doubt pleased by the move, having literally gone through hell and high water during the preceding months

His passage was uncontested, thanks to some well-planned diversions. Colonel Benjamin Grierson led 1,700 Union cavalry on a raid behind Confederate lines, ripping up railroad lines and diverting Confederate attention away from Grant. Sherman’s men also staged maneuvers that looked like the Federals were going to attack Vicksburg from the north, near Chickasaw Bluffs. It was only a diversionary feint, but the Southerners were completely taken in.

The next week or so would establish Grant’s real worth as a field commander. Once his army was across the river, conventional military wisdom would have had him drive north toward Vicksburg, at the same time keeping contact with his communication and supply line on the Mississippi.

Grant had no intention of being conventional. He knew that Confederate General Joseph Johnston was at Jackson, the Mississippi state capital, 40 miles from Vicksburg, trying to scrape together additional Southern forces. Johnston commanded the Department of the West, one component of which was Pemberton’s Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana. If he besieged Vicksburg and left Johnston unmolested, Grant might eventually regret it. Johnston might hit Grant on the right flank and perhaps even relieve Vicksburg.

In Grant’s view, it was better to drive inland and take on Johnston. Once Johnston was neutralized, he could turn back and attack Vicksburg. To drive inland meant breaking loose from his supply and communications, but Grant was confident his men could live off the land. He was right, but the maneuver produced some anxiety for Lincoln and the North, because for more than two weeks Grant and his army disappeared.

When the Army of the Tennessee finally reappeared, it had just completed a military tour de force. In 17 days Grant’s army had marched 180 miles and fought and won five engagements against Confederate forces. The last engagement, a clash at Big Black River Bridge on May 17, was only 10 miles from Vicksburg. The Confederates had not only been defeated but suffered a collapse that ended in a near rout. Exhausted, ragged, and parched with thirst, the dispirited rebels quickly streamed back to Vicksburg.

A Vicksburg woman was shocked at their appearance, describing them as “wan, hollow-eyed, ragged, footsore and bloody.” This exhausted and demoralized army seemed in no condition to defend the city. Their arrival also meant there would be some 30,000 extra mouths to feed.

Vicksburg was nicknamed the Gibraltar of the Confederacy, a description that was not far off the mark. The main defensive line around the city ran 61/2 miles. Nature lent a hand with terrain of various heights, including lofty bluffs and hills with steep elevations. The natural features were augmented by forts, trenches, redoubts, and lunettes.

Major fortifications defended the city’s approaches. There was Fort Hill, Stockade Redan, 3rd Louisiana Redan, Great Redoubt, Railroad Redoubt, Square Fort, and South Fort. Fort Hill was sat atop a high bluff north of the town, and Stockade Redan dominated the Graveyard Road approaches to Vicksburg. Railroad Redoubt protected the gap that allowed the vital, at least in normal times, railroad line to enter the city. A salient along Hall’s Ferry Road was protected by Square Fort.

Grant decided to assault Vicksburg immediately in hopes that the city would fall quickly. His army was in an ebullient mood, having experienced a string of successes, and Confederate morale seemed low after the last devastating defeat. Then, too, Grant was worried about the potential fire in the rear; that is, Johnston might have received a drubbing, but there still was a good chance he could gather forces and march to Vicksburg’s relief.

The Army of the Tennessee comprised three corps: XV Corps under Sherman, XIII Corps under Maj. Gen. John A, McClernand, and the XVII Corps under Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson. Grant ordered the assault to start at 2 pm on May 19.

Although the Union troops were in fine fettle and ready to go, they sweltered under a torrid Mississippi sun to which the men had a hard time adjusting. Private William Morgan Davies of the 95th Ohio of the XV Corps was part of the reserves assigned to exploit any breakthrough. He later recalled the extreme heat, noting that he and his comrades had “perspiration oozing out at every pore.”

The attack was launched on schedule, long lines of blue-coated infantry moving forward at a brisk pace, their regimental flags waving proudly. The Stockade Redan proved a particularly tough nut to crack. Confederate artillery was well served, and gouts of smoke and flame tore bloody gaps into the well-ordered ranks. Confederate rifle fire also peppered Sherman’s men, and scores of stricken soldiers crumpled to the ground as the lead bullets slammed into their bodies.

The first wave attack was a failure, so the bluecoats fell back to their own lines. Grant ordered his artillery to soften up Confederate positions, and then troops from Maj. Gen. Francis P. Blair went forward to see if they could make a breakthrough.

The bluecoats scrambled up Stockade Redan’s abatis then had to negotiate a six-foot deep, eight-foot wide ditch under heavy rifle and artillery fire. Once past these obstacles, the Union troops had to scale the redan’s 17-foot-high wall. Some made it into the ditch but got no farther. There was little left to do but to call off the attack.

Bloodied but unbowed, the Army of the Tennessee was still confident it could take Vicksburg by general assault. It was obvious the Confederate defenses were strong, but the memory of the brilliant maneuvers of the past weeks sustained the army’s basic faith in itself and its abilities.

Grant decided to renew the assault on May 22, but this time the preparations were going to be done with much more care. This would be a grand general assault, with all three corps taking part in the operation. Sherman would take the right, McPherson the center, and McClernand the left. Grant hoped that such a major effort would achieve a breakthrough.

The attack began at 10 am after a preliminary bombardment of four hours. Once again, Sherman’s men were going to have a crack at the Stockade Redan, but this time the operation included some thoughtful planning. A storming party of about 150 men would take the lead, carrying scaling ladders, roughhewn logs, and some lumber. Being in the vanguard was bound to attract Confederate fire, so chances of surviving were slim. Because of this, only unmarried volunteers were accepted.

The first volunteer to come forward was Private David Day of the 57th Ohio, who was only 16 years old but already a veteran with a year’s soldiering under his belt. The idea was for some of the men to carry the logs, two men to a log, and dash forward toward the redan ditch. The men in the first group were to throw the logs across the ditch, making the foundation of a bridge. A second group would bring up lumber planking to complete the span. A third group would bring the scaling ladders to further assist in the assault.

Once the bridge and scaling ladders were in place, the rest of Maj. Gen. Francis Preston Blair’s 2nd Division would move forward along a narrow front, a blue-clad column that just might break through Southern defenses. But things went sour quickly. Colonel William Wallace Witherspoon’s 36th Mississippi Infantry bravely defended the Stockade Redan. The rebels poured a murderous fire into the first group.

To make matters worse, the first group had to cross nearly a quarter of a mile of open ground to reach its objective. By the time they reached the ditch about half were killed and wounded, and so many had fallen that there were not enough logs or lumber to make a bridge. As the survivors sheltered in the ditch, they found that the Confederates could not depress their guns low enough to get them. Frustrated, the Southerners improvised and began lobbing and rolling 12-pounder shells into the ditch.

Luckily for the first group, many of the fuses were too long, allowing the bluecoats a few extra seconds to throw the lethal shells back to the Confederates. Still, some shells did detonate in the ditch, and the explosions blew off heads and limbs with horrifying ease. Sherman’s advancing infantry brigades also made little headway; as one Union soldier remembered, men “fell like grass before the reaper.”

Sherman, a tough soldier not known for being squeamish, finally threw in the towel. “This is murder,” he said. “Call those troops back.” All along the three-mile assault line the story was the same. As Grant later remembered, “The attack was gallant, and portions of each of the three corps succeeded in getting up into the very parapets of the enemy and in planting battle flags upon them; but at no place were they able to enter.”

Survivors who had managed to come so heartbreakingly close and even momentarily seize parts of the Confederate fortifications, had to make their way back to Union lines under the cover of darkness. Private Day survived. His courage under fire won him a Medal of Honor.

Grant’s casualties for the day amounted to about 3,000 men; Southern losses were around 500. The troops had fought eight hours under a burning sun. It was so hot that some were felled by heatstroke, not bullets. Union dead and wounded lay sprawled in the killing ground in front of the fortifications, trapped in a kind of no-man’s land between the two armies.

Apparently afraid to show weakness, Grant at first refused any notion of a truce to collect the wounded and bury the dead. Hundreds of corpses blackened and swelled in the heat, producing a sickening stench, but the plight of the wounded was truly pitiful. Grant relented, and a truce was declared on May 25.

By then the corpses were so foul and crawling with vermin they were almost indescribable, but the grim burial work had to be done. The thirst-crazed wounded, who somehow managed to survive the ordeal, also found help. But it was also a time for a brief fraternization between North and South. Johnny Reb and Billy Yank swapped coffee and tobacco, played cards, and for a few brief hours forgot politics. Some were reunited with old comrades, people they had known before the war.

The assault gamble had failed. There was nothing to do at that point but to conduct a full-scale, traditional siege with basic techniques that had not changed much since the days of renowned French military engineer Marquis de Vauban in the 17th century. And while bombardments pounded the city, and trenches and parallels were dug, the noose would be tightened to make sure no supplies would reach the beleaguered city. Vicksburg would starve.

The gently undulating hills and high bluffs were made out of loess, a fine-grained clay soil that was fairly easy to excavate. As the Union bombardment intensified, more and more citizens burrowed into the hills to find shelter; as one woman put it, “Caves were all the rage.” Their elegant antebellum homes were abandoned, replaced by man-made caverns that were dirty, stifling, and plagued by mosquitos and snakes.

Shelling was nearly around the clock, but familiarity did not lessen the terror. Constant detonations hammered at the ears and threw a fine mist of smoke, broken glass, plaster, and wood into the air that made breathing torture at times. Rations were cut again and again, until there was barely enough to keep body and soul together.

Indeed, hunger was probably the worst part of the siege. Dogs and cats quickly disappeared from Vicksburg streets, and there was little doubt they had been consumed by ravenous soldiers and citizens of the town. Mule meat began appearing in Vicksburg shops, and when that ran out, skinned rats were also sought after.

A Vicksburg soldier’s ration was one cup of rice and one cup of cowpeas. Cowpeas were not a true pea but a kind of rough bean that was normally fed to cattle, hence the name. Rumors of hording by local merchants spread like wildfire, but nothing could be proved.

The artillery shells were not as destructive as those used in 20th-century wars, but direct hits were horrific enough. As casualties multiplied, row after row of hospital tents were erected in parks and on other open ground. Local minister William Foster visited the tents and was appalled at what he saw. “Every part of the body is pierced,” he wrote later. Foster saw a man whose hair, eyebrows, and even eyelashes were burned off, and his head was a blackened mass. Still another had his jaw torn off, his face horrific to behold.

That was bad enough, but the tents also sheltered men tormented by infectious diseases like yellow fever, malaria, measles, and dysentery. Conditions were bad even by 19th-century standards; dirty bandages covered wounds infected with maggots, and flies swarmed everywhere.

As May turned to June criticisms of Vicksburg’s commander mounted. Pemberton was the wrong man at the wrong place. He was vacillating and unsure of himself, but like most weak men he took refuge in both bombast and following orders to the letter. Confederate President Jefferson Davis had insisted he hold Vicksburg and hold it he would, with little thought of changing circumstances that might have made Davis’s orders obsolete. He also issued a proclamation that was aimed to restore his flagging reputation.

“You have heard that I was incompetent, and a traitor, and that it is my intention to sell Vicksburg,” he said. Pemberton went on to say that he was determined to hold out to the last grain of corn and until the last animal was consumed. Even then, there would be no talk of surrender until the “last man shall have perished in the trenches.” Few believed these statements, especially when it was well known he originally hailed from the North.

Pemberton’s origins did help matters. He was a Northerner by birth, one who had joined the Confederacy, so it was said, mainly because his wife was from the South. That made it sound as if he were lukewarm to the Confederacy at best. Others harbored darker thoughts against him. They suspected he might be a Northern spy.

Disgusted by their Northern commander, Vickburg residents pinned their hopes on Johnston. After all, here was a Southerner born and bred and a real gentleman to boot. The rumor mills began churning out stories that Johnston was gathering forces at Jackson and that a relief expedition could be expected soon.

What they did not know was that Johnston had already written off Vicksburg. He did manage to patch together a ragtag force of 30,000 men, but Grant by then had 70,000 battle-hardened veterans at his command. Johnston also was beset with insufficient supplies, transportation, and weapons for his army. Never one to mince words, Johnston told his superiors in Richmond on June 15, “I consider saving Vicksburg hopeless.”

At one point Johnston urged Pemberton to break out and join him instead. Pemberton and his army stayed put, partly because of the commander’s vacillation. As time went on, what Pemberton thought or did became irrelevant. By the end of June, the troops were literally starving and in no condition to fight their way out of the Union siege.

Grant’s Yankees began to start tunnels, a time-honored siege technique. The idea was to burrow under Confederate fortifications, place explosives under them, and literally blast a hole in the defenses that could be exploited by infantry. At first the Confederates were puzzled by signs of Yankee activity, but they soon caught on and began sinking countermines.

The Rebels dug with an earnestness born of desperation. They had to find the enemy’s tunnels, but it was an exercise in frustration for the most part. At times they could hear the sounds of picks and shovels, and sometimes the muffled but unmistakable sounds of Yankee conversation through the earth. They never did manage to intercept any of the Union tunnels.

In the meantime, Grant’s miners had successfully dug a tunnel under the 3rd Louisiana Redan, though the Confederates were completely unaware of its presence. Slowly but surely the Union soldiers packed 2,300 pounds of explosives under the redan, and when all was ready detonated it.

The effect was horrific. The fortification momentarily disappeared, replaced by a huge flaming geyser that suddenly burst from the ground with an ear-splitting roar. As the blast lost some of its momentum, soil, blood, charred wood, and human body parts came cascading down. The explosion ripped a 40-foot-wide and 13-foot-deep hole out of the redan, an opening that seemed ripe for Grant’s men to exploit.

Union infantry surged forward, including the men of the 45th Illinois Regiment, but the Confederates recovered quickly from the initial shock. The fighting was savage and often hand to hand, and it seemed for one breathless moment that the Federals were on the verge of success. It was not to be. Confederate resistance stiffened, and eventually the Yankees were thrown back.

The Confederates had won, but in a way it was a pyrrhic victory they could ill afford. It was said that as the Redan battle raged a steady stream of Confederate wounded came back to the town in a mournful procession. Some had skulls bleeding from rifle butt wounds, while others clutched their abdomens so that their intestines would not spill out. The makeshift hospitals were already overflowing, which meant the freshly wounded would not receive adequate care.

But spectacular fights like these were relatively rare. For Union soldiers, the siege was a combination of sweat, toil and boredom. Vicksburg, like the confrontation at Petersburg, was a chilling foretaste of World War I half a century later. The trenches were hot and dirty, but if a man tried to look over the top of these excavations he might fall victim to a sniper. Yankee sharpshooters fired approximately 150 rounds a day.

By early, July Vicksburg was on its last legs. Earlier in the siege, some provisions had been made for a last stand just in case the city’s outer defenses had been breached. Roadblocks had been thrown up at major intersections, but there were fewer and fewer fit soldiers to man them. The ceaseless pounding by Union artillery continued, but not many cared.

Roads were pockmarked by shell craters, and homes displayed varying degrees of damage. Bombed-out houses often were looted as well. Smaller buildings like sheds were deliberately dismantled for precious firewood. Since most of the civilians were sheltering in caves, their abandoned homes, damaged or not, made parts of the city look like a ghost town.

Finally, the emaciated garrison had had enough. Famished, reduced to ragged skeletons, they could endure no more. The soldiers drafted a collective letter to Pemberton which they titled “An Appeal for Help.” Hunger had driven them to desperation. “You had better heed a warning voice, though it is the voice of private soldiers: This army is now ripe for mutiny, unless it can be fed,” the letter read.

Pemberton did heed the advice. The commander contacted Grant under a flag of truce and surrender terms were discussed. At first Grant wanted nothing less than unconditional surrender but later thought better of it. Pemberton’s starving army would be granted parole in part because there was not sufficient transport to convey the thousands of Confederate prisoners north to Union prisons. Parole therefore was granted in return for a pledge not to take up arms against the Union again.

The formal capitulation came at 10 am on July 4. There was some tension at Pemberton’s headquarters when the two commanders met again to sign surrender documents. The Confederate officers were rude. They did not furnish a chair for Grant and ignored his polite request for a glass of water. Grant’s own staff was outraged, but the general himself was calm, even nonchalantly taking out a cigar and puffing on it during the proceedings.

For the most part, though, humanity and kindness, not politics and bitterness, was the order of the day. The Stars and Stripes was raised over Vicksburg at Courthouse Hill,

and about the same time long lines of blue-clad troops entered its battered streets. Though they were triumphant, the Northerners were not in the mood for celebration once they saw the condition of Vicksburg’s soldiers and citizens.

Union soldiers passed out food, and Grant ordered that Federal rations be distributed freely. Confederate soldiers were dressed in dirty and ragged uniforms of gray or butternut, though a few were clad in undyed wool, in tunics that were a kind of dirty, off-color white. Many were lice-ridden and so skeletal the hip bones of some of them had actually broken through the skin. Others could barely walk more than a few feet without assistance.

When Union supply boats landed at Vicksburg, famished citizens crowded the docks and took as much food as they could carry. On the whole, Union soldiers and Vicksburg residents got along well under the circumstances. Yankees helped matters by breaking into stores in the commercial district where they found hidden stockpiles of food stored in barrels and sacks. There were piles of canned fruit and other goods. The discovery confirmed the rampant rumors of hording that circulated during the siege. All such provisions were immediately distributed to the townspeople.

The Union triumph at Vicksburg meant that the Confederacy was split in two. As Lincoln put it, the Mississippi could now flow “unvexed to the sea.” At the same time Vicksburg was surrendering in the West, the Union defeated General Robert E Lee at Gettysburg in the East. These twin victories doomed the Confederacy, even though more hard fighting was to follow.

I was intrigued with the disparaging comments on the Confederate ration during the siege of Vicksburg “A Vicksburg soldier’s ration was one cup of rice and one cup of cowpeas. Cowpeas were not a true pea but a kind of rough bean that was normally fed to cattle, hence the name.”

Cowpeas are better known as Black eyed peas and cooked with rice, some spices and a little ham or bacon it becomes a famous and very tasty Southern dish Hopping John. I eat it fairly often and I am definitely not in a siege. Good food, very nutritious. Likely the Federals were subsisting on Crackers or something even less appealing. They did have access likely to meat fruit and other produce.

Nice map.