By John Mancini

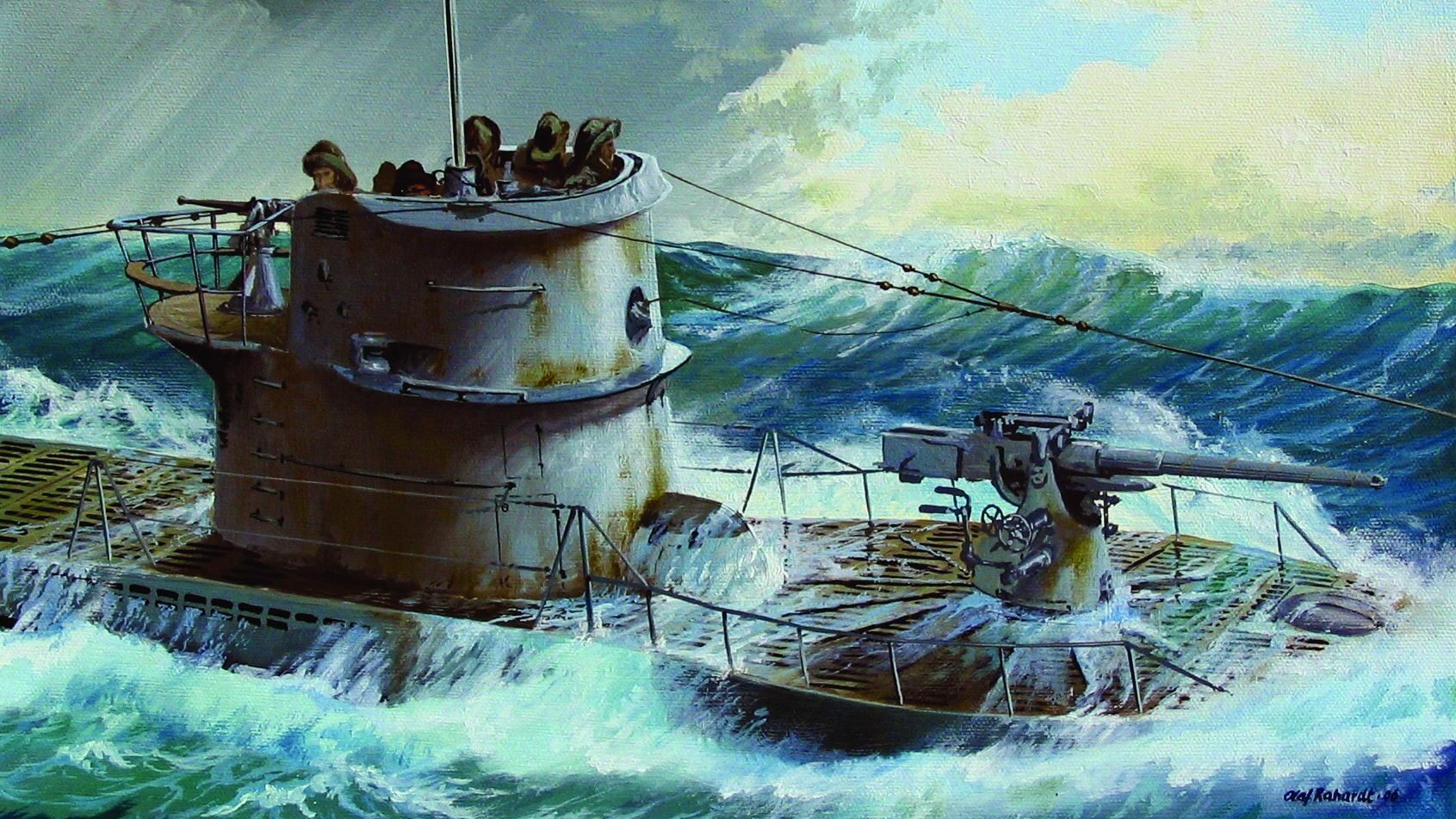

In the early morning of Monday, November 9, 1942, the german U-boat U-518 surfaced off the bleak Quebec coast. Seamen scrambled onto the wet, slippery deck and quickly launched a wooden dinghy into the cold, black water. The German sailors rowed silently through the darkness to the rocky shore.

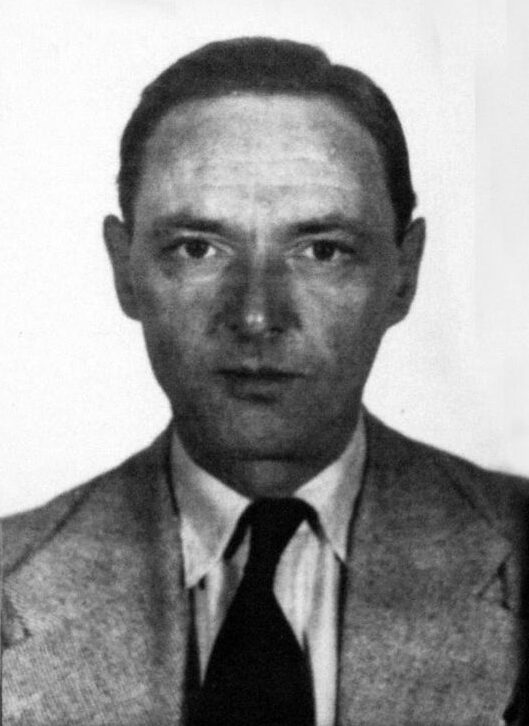

A lone passenger grabbed several suitcases and leaped off the swaying craft onto the beach. German agent Werner Alfred Waldemar Janowski, code-named Bobbi to the Abwehr, had been inserted into Canada.

The 38-year-old Nazi swiftly changed from a naval uniform into civilian clothes and by daylight was in the small town of New Carlisle, four miles from the landing site. He presented himself as a traveling salesman when he registered at the New Carlisle Hotel. Janowski stated that he would not be spending the night and asked to register for just a bath and breakfast.

The stranger immediately aroused suspicion in the front desk clerk when he paid for the room and food with currency that was out of date and circulation. The clerk also noticed that the stranger’s clothes were odd and very much out of style. Janowski reported that he had arrived by bus from a neighboring town, obviously unaware that bus service had been discontinued from that community.

The clerk’s suspicions continued to grow. The people of the isolated coastal town were very aware that Nazi submarines operated near their shore. Merchant vessels were frequently sunk by U-boats within sight of land. Peculiar nighttime sounds that came from the ocean were known to be surfaced enemy submarines recharging batteries. It was also well publicized that eight German agents had landed by submarine in the United States six months earlier.

Sensitive to the Nazi threat to North America, the hotel clerk became even more observant of his puzzling customer. Janowski became increasingly nervous in response to casual but pointed conversational questions and asked about the departure time of the next train to Montreal. The clerk replied that it would leave in about one hour. The stranger asked for directions to the depot, declined the offer of a ride, and abruptly left the hotel.

The desk clerk’s suspicions of a possible enemy agent were quickly confirmed by a yellow matchbox that the man had left behind in his rush to the train station. The matchbox was marked made in Belgium and lacked the required import tax stamp.

Constable Alphonse Duchesneau of the Quebec Provincial Police was immediately contacted by the hotel clerk. The policeman was skeptical of the allegations but dashed to the railroad station along with the astute clerk and boarded the train.

Janowski was spotted instantly. Constable Duchesneau confronted him and demanded to see his papers. The German nervously handed him two documents. The first was a Canadian National Registration Certificate identifying him as a resident of Toronto, Ontario, but the form was printed in both French and English. This type of bilingual printing of official documents occurred only in the province of Quebec. The other document was a Quebec driver’s license, but with a Toronto, Ontario, address.

These inconsistencies raised too many questions. Dushesneau demanded to search Janowski’s luggage. The search was unnecessary to expose the German as a spy: he blurted out, “I am caught! I am a German officer!”

Duchesneau proceeded to examine the German’s suitcase, which contained spiked brass knuckles, approximately $6,000 in currency, pills, a loaded .25-caliber automatic pistol, and a 40-watt transmitter-receiver radio. The spy from the sea had been arrested 12 hours after he had come ashore in Canada.

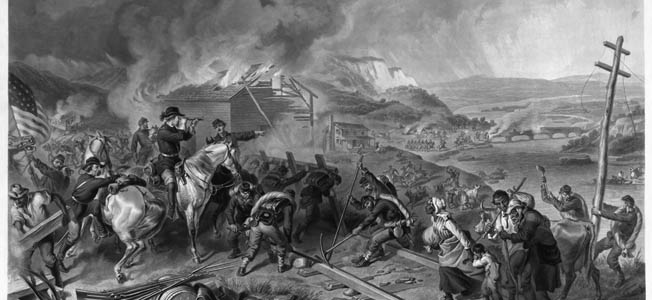

The case of the spy from the sea was transferred to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. The elite law enforcement organization was established in May 1873 to suppress heavily armed gangs of whiskey traders who controlled the western Canadian prairies. Throughout its colorful history, the Mounted Police had performed both law enforcement and military missions for the Canadian government. During the Riel Northwest Rebellion of 1884, Mounties served as scouts for the Canadian Army; and during the 1899 Boer War, Mounted Police performed as cavalry with the British forces in South Africa.

Mounties were with the Canadian Army in France and Belgium during World War I and with the Allied Expeditionary Force to Siberia in 1918. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police are best known for their Arctic dogsled patrols, but battling urban crime and international threats became new missions during the early 20th century.

A special branch of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police was established and became actively involved with counterintelligence operations after the 1917 Russian Revolution and the rise of the Canadian Communist Party. A bloody general strike in Winnipeg, Manitoba, during the summer of 1919 enflamed fears of a Bolshevik threat to the western provinces, and there was an increase of communism within the Canadian labor movement after World War I. Mountie John Leopold infiltrated the Canadian Communist Party in 1920 and worked under cover for eight years. His skillful counterspy activities led to the arrest and conviction of many top party leaders on various conspiracy charges.

After Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany in 1933, Mountie counterspies shifted their attention from communist conspiracies to the Nazi threat. RCMP agents swiftly penetrated Nazi and fascist organizations. When Great Britain and Canada declared war on Germany in September 1939, Mountie counterespionage agents had compiled a list of “dangerous persons” who were immediately arrested and placed into wartime detention and internment. Nazi Germany would have to reestablish its Canadian spy network by inserting new agents.

Mountie Clifford Harvison was assigned to lead the Janowski espionage investigation, which was codenamed Watchdog. The seasoned Mountie criminal investigator had spent years in Montreal during the 1920s arresting counterfeiters, drug dealers, and gangsters involved with smuggling liquor into the United States. Harvison described his experiences as simply dealing with booze, brothels, and drugs.

Harvison and the urban Mounties were called the “Horsemen” by the Montreal criminals who viewed their aggressive law enforcement tactics as similar to the Western frontier style of their predecessors. In 1938, Inspector Harvison was given command of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Investigation Unit, which included counterintelligence duties.

When Harvison began his questioning of the spy from the sea, Janowski claimed to be a U-boat naval officer who came ashore on a simple reconnaissance mission and then decided to desert. The German adamantly denied that he was a spy or a saboteur. However, Janowski could not answer basic questions about a submarine.

Under aggressive interrogation by Harvison, Janowski quickly dropped his cover story and revealed that he was in fact a German Army officer who had lived in Canada from 1930 to 1933 and was on an espionage mission for the Abwehr. Janowski appeared to become cooperative and further stated that his mission was a prelude for other Nazi espionage and saboteur U-boat landings.

The main objective of the German agents was to sabotage war industry plants in both Canada and the United States. Harvison suggested to Janowski that he had been set up to fail by German intelligence by giving him money and documents that would arouse immediate suspicion. The astute Mountie investigator perceived an exploitable weakness in the otherwise overconfident German. The Nazi agent feared that he would be hanged as a spy if he did not cooperate.

Harvison exploited Janowski’s fear of execution and suggested that he work for the RCMP. Janowski accepted the possibility that he had been betrayed and agreed to work as a double agent. And Harvison was convinced of the German’s sincerity to cooperate and participate in this counterintelligence operation against the Abwehr. The Mountie counterspy hoped to lure other Nazi agents into a Royal Canadian Mounted Police counterespionage trap.

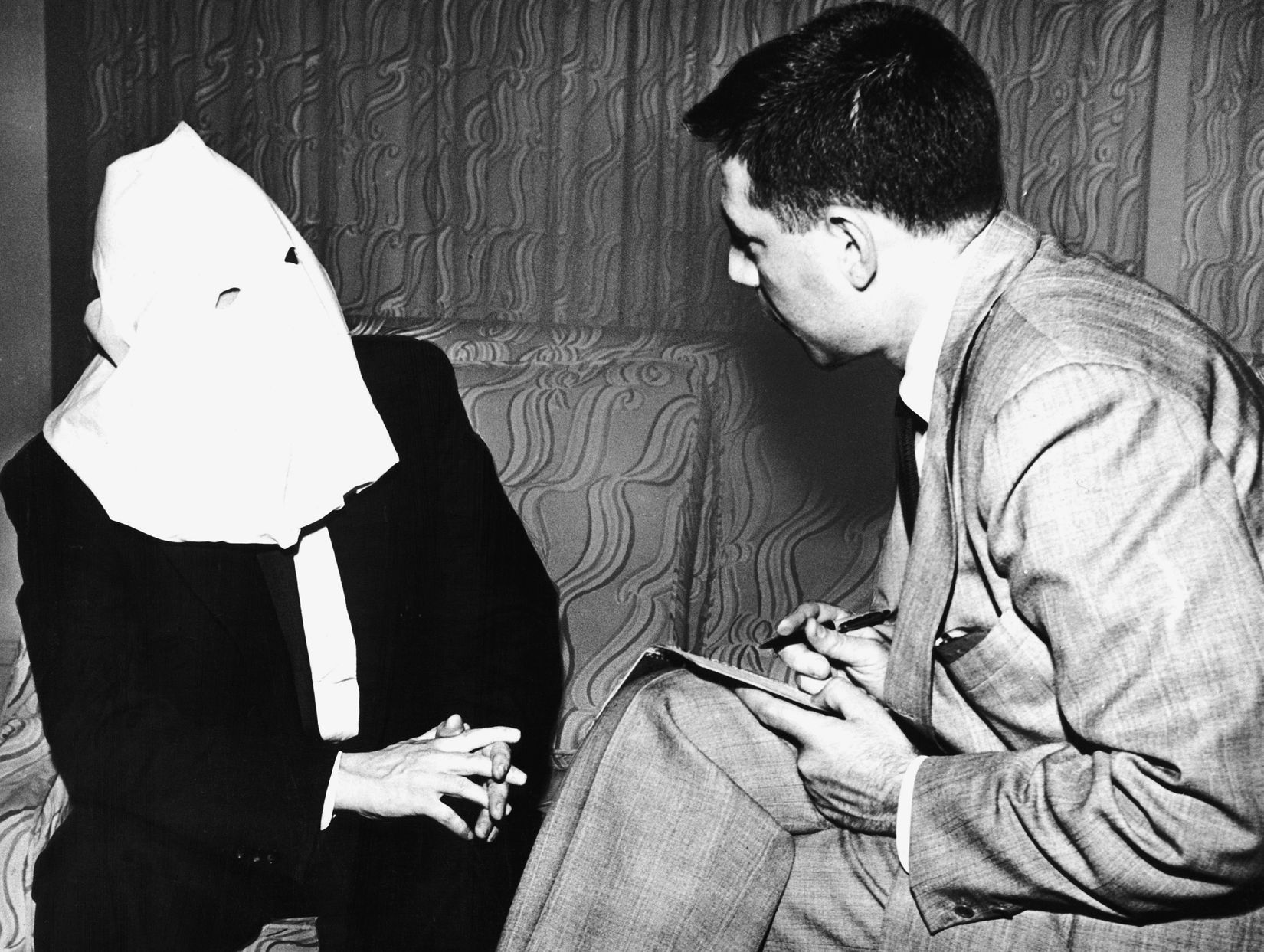

An agent from British Intelligence joined the Mountie team that included a code expert and a specialist on radio messages. Transmissions to Abwehr headquarters in the German seaport city of Hamburg began from a house in the residential area of Montreal. The transmissions were made twice a day for the next nine months. However, it slowly became apparent that the communication was very one-sided. German intelligence requested information on military units in Montreal and Quebec City, antisubmarine defenses on the Saint Lawrence River, and National Registration Certification documents.

All of the Abwehr inquiries suggested plans for future espionage and sabotage missions. The Mountie counterspies replied with sanitized military intelligence, but the Germans provided no information. The Mounties pressed harder through Janowski’s transmissions for intelligence regarding other Nazi agents in Canada. Janowski was directed to use the ploy that he had been alone in enemy territory for almost one year and was in need of finances. Who could he contact in Canada for help?

However, his German handlers did not deviate from their pattern. They simply ignored these transmissions and replied with their own questions. Finally, it became painfully apparent that the captured spy could not be used to lure any more Nazi agents into a Mountie trap.

Questions arose to try and explain the Abwehr’s response. Had Janowski’s arrest been too publicized and therefore known in Germany? Had he remained loyal to the Abwehr and cleverly alerted Hamburg through predetermined codes in his transmissions that he had been captured and was under the control of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police? The counterespionage operation was discontinued, and Janowski was turned over to the British and transported back to England.

As the Nazi espionage threat subsided in Canada, new dangers from the Soviets emerged. In September 1945, Igor Gouzenko, a member of the Red Army Military Intelligence and a code expert at the Russian embassy in Ottawa, defected to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Gouzenko brought documents that revealed startling and chilling information regarding the Soviet penetration of the Canadian, British, and American governments. Prominent Canadian scientists and government officials were identified as being active members of Soviet espionage networks.

The chilling revelations also confirmed that the Canadian Communist Party was under Moscow’s control and not simply a radical but independent domestic political group.

William Stephenson, the World War II spy master known as Intrepid, became the coordinator of the operation that was codenamed the Corby Case, named after Corby’s Canadian rye whiskey that Stephenson and his staff consumed during late-night strategy sessions.

Cliff Harvison, now chief of the RCMP Intelligence Branch, became a major player in the Corby Case. He supervised the security protection of Gouzenko and his family at Camp X, the Canadian World War II spy school near Toronto. Harvison also led the methodical investigation of the Canadian officials who had been identified as having subversive connections to the Soviet Union. Mountie counterspies pursued intensive interrogation of the Canadians mentioned in the Soviet files, which resulted in many arrests and convictions.

Harvison continued his successful career with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and in October 1960 he was appointed commissioner. Janowski remained an Allied prisoner until 1947. His postwar life was characterized by divorce, marginal employment, and financial problems.

During an official visit to Germany in 1963, Harvison received a surprising phone call. The caller was Werner Alfred Waldemar Janowski. He requested a meeting for the following day. The Mountie agreed, but Janowski did not come. However, the German spy sent a short telegram to his wartime adversary. “Cannot see you after all. Only wanted your pardon for causing trouble during the last war. All the best.”

A display depicting the Janowski affair, entitled, “The Spy from the Sea,” can been seen at the RCMP Centennial Museum in Regina, Saskatchewan, along with the rest of the colorful history of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

Author John Mancini is a retired U.S. Army colonel. He resides in Sierra Vista, Arizona.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments