By Don A. Gregory

Frieda’s last doll was bought for her by her father, August Streit, in 1938. At age 10 she was really too old for dolls, her father thought, but he would buy her this last one.

The two of them traveled to Nuremberg to a large toy store where the beautiful doll in the window immediately caught Frieda’s eye. Even though she eventually looked at almost every doll in the store, she still came back to that one and finally asked her father to buy it for her. It was 35 marks, a sizable amount of money in 1938, but he bought it for her anyway. It had been a good year so far for Frieda. She had even seen one of the great marvels of the time—the Graf Zeppelin—in flight. Germany was indeed a wonderful place to be, she thought, and she was lucky to have two parents who loved her very much. The world was just about perfect for a 10-year-old girl.

Then the war came, and everything became hard to get. In 1938-1939, the people who had money in Frieda’s town of Ebermannstadt bought soap, which sounds like an odd thing to do. There were plenty of people around who remembered World War I and knew well the things that would soon be in short supply.

Frieda was 11, and her older half sister was 17 when the war broke out. Both of them knew that something big was happening but did not quite understand what all the excitement was about. Hitler had been the German chancellor for six years and was the only leader that Frieda could remember, not that she paid much attention to such things anyway. The war, if it came, would surely be somewhere far away, she thought, and besides, she had work to do.

It was hard helping her mother cook for the family, especially with rations of only half a pound of sugar a month, and since they did not have any babies in the family all they could get was blue milk, so watered down it looked perfectly blue. Beef and pork were rare commodities, but they had their rabbits that multiplied—like rabbits. Her father could prepare rabbit that could compete with the best sauerbraten in Germany. Later in the war they would also slaughter a few of her father’s pigeons to supplement the slim meat ration. Her mother would add whatever meat they had to it and make something good. None of them ever went hungry but they also never knew for certain what had gone into the meals. They were just glad that they had those rabbits and pigeons.

Frieda was born January 16, 1928, to August and Anna (Kirchberger) Streit. Her mother was originally from Nuremberg; her father was from Saxony, and they had cousins in Munich. At one time there was some concern that her mother might have had some Jewish ancestry, but this was ruled out through an investigation done by the government. They were very careful in those sorts of things. Freida’s mother had four brothers who would all eventually leave Germany and move to New York, the first in 1922, and they were all there by the time the war started. Her mother had one child named Annemarie from a previous marriage.

August never adopted Annemarie but nevertheless treated her as his own daughter, and she was always an older sister to Frieda. Annemarie was 11 when the National Socialists and Hitler came to power and had enrolled in the BDM (Bund Deutscher Mädel) soon after its creation in 1930. Its proper title was The League of German Girls of the Hitler Youth. Early in its history, the BDM stressed education for its girls and encouraged them to finish school and learn a skill. This was relatively rare for girls at the time, but many of the women who became regional and national BDM leaders were successful women who held university degrees, and the younger girls looked up to them as role models.

The requirement that most girls dreaded was the one year of service to the Reich. This could be accomplished in many ways. In fact, Frieda remembered one girl who was able to put in her year of service right at home because her family had a few cows. She was allowed to use her work helping with the milking and feeding as service, which no doubt it was, but it was as much a service to her family as to the Reich. This didn’t seem quite fair to Frieda, who would soon have to leave home and give a year to the government herself. BDM girls were also expected to help with charitable work, such as collecting money for the WHW (Winterhilfswerk), which helped poor families by distributing coal and warm clothing to them during the winter months.

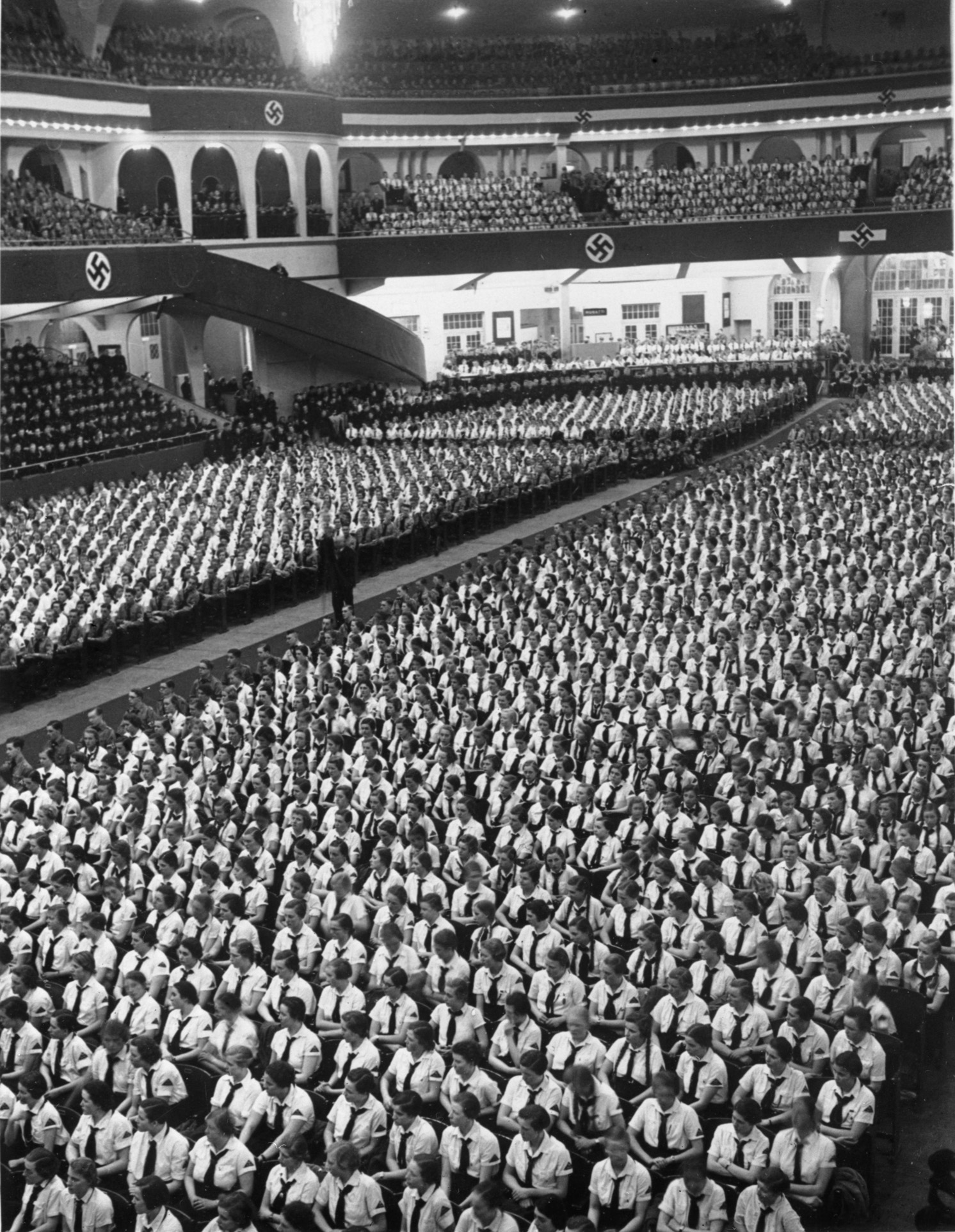

The Nazi Party was founded in 1920, and the organization of youth groups was an important part of its mission, even in the early years. In fact, the Hitler Youth was the second oldest paramilitary organization in Nazi Germany. Only the SA (Sturmabteilung) was older. The first Nazi youth group was the Greater German Youth Movement, or Grossdeutsche Jugendbewegung, founded in 1923. It officially became the Hitler Youth in 1926, with Baldur von Schirach as its leader.

The young women of the Reich became loosely organized as the Hitler Youth Sister Community, or Hitlerjugend Schwesternschaften, which eventually became the BDM in 1930. The organization rose to 25,000 members even before Hitler became chancellor in January 1933.

The adult National Socialist women of the Reich had their own organization called the NSF (Nationalsozialistische Frauenschaft), and its leader, Gertrud Scholz-Klink, initially wanted control of the young girls’ organization as well, but Hitler decreed that all youth would be under Schirach. The leader of the BDM was a Berlin psychiatrist, Dr. Jutta Rüdiger. Her official title was Reichsreferentin. She reported directly to Schirach, who generally left her to manage the BDM as she saw fit.

Membership in any Hitler Youth organization was voluntary until 1936, although most who qualified became members as early as they could, even before the Hitler decree that made it mandatory. There were more than seven million members of the BDM by the end of 1936. The decree, in any case, was not enforced until the beginning of the war, but it did make the Hitler Youth eligible for government funding, which the organization used to expand its programs. Frieda could sense that things were changing for girls her age, and it was an exciting time to be alive.

Annemarie joined the German government workforce, the RAD (Reichsarbeitsdienst), when she was 21 years old and first worked in a plant nursery, then in a butcher shop. Normally, young women joined either the RAD or the Frauenwerk after they turned 18, but they could also remain members of the BDM as long as they were not married and had no children. The Frauenwerk was not a rigidly organized Nazi institution like the NSF, and party membership was not required to join.

Annemarie’s last job had definite advantages for the family because the butcher saved any excess meat scraps for her. Unfortunately, this job did not last long, and she was soon selling tickets for a streetcar company. The BDM magazine, Das Deutsche Mädel (The German Girl), often featured ads for stenographers and nurses and had articles about girls working as ticket agents on trains or as nurses. The stories were designed to motivate young girls to do their part in the war effort, and the publicity worked well for the party. Girls Frieda’s age and older volunteered by the thousands.

Frieda’s mother joined the Frauenwerk soon after the war began because by then it was officially mandatory, and it also assured that the family would continue to receive its ration stamps for things ranging from food to shoes. Without the stamps, these things were only available on the black market, and people were told that if they were caught buying things this way, they could be shot. Frieda did not know if this was really true; she knew people who would occasionally buy things on the black market, but she never knew anyone to be shot for it. Sometimes it was the only way to get things that were really needed, like extra sugar and cooking oil for a Christmas cake. Even during the war, some things just could not be done without, especially at Christmas.

In school, the girls studied the usual reading, writing, and arithmetic, but there were also classes in religion, local and area history, singing, and handiwork which included knitting, sewing, and crocheting. They had about seven years of traditional schooling, then Sunday School after that. The boys had some of the same basic classes but also had additional instruction in recognizing enemy aircraft, marching, and weapons. Later in the war, the boys’ main task was ditch digging. They dug antitank ditches everywhere, and some of the ditches are still visible today.

The BDM’s goal was to prepare young girls for their future roles in the community, and as an incentive to participate the organization offered many things that appealed to teens such as weekend outings and reduced prices at movie theaters. The girls also attended camps in the country that could last several weeks and participated in sporting events, just like the boys. BDM groups usually met twice a week; one of the meetings was devoted to sports, the other to Heimatabend (home evenings) with the girls learning crafts that would be useful to them as homemakers.

During the war, Frieda and the other girls her age in Ebermannstadt wrote letters to soldiers and packed boxes of baked goods and other things for them. The war, however, caused a gradual change in the BDM. Women and young girls began to be seen more as keepers of the home fires while the men were fighting, and they were also called on to fill jobs that were once exclusively reserved for men, such as air raid wardens and military signals specialists. This was in addition to their traditional wartime roles as nurses and hospital support personnel.

In 1941, Frieda was confirmed at age 13 in the Catholic faith at the Dreieinigkeitskirche (Holy Trinity Church) in Streitberg. Her family was Protestant, but it was not uncommon for her to go with her friends to Lutheran or Catholic services in Streitberg, as there was no Lutheran church in Ebermannstadt. A year after her confirmation, she joined the BDM. Her older sister who was 20, had completed her year of service to the Reich by then.

The opportunity to learn a trade actually appealed to many of the young women of Germany, who had never had this chance before Hitler came to power. It was a way for the girls of the Reich to prove they were just as valuable as the boys and that they could make their own contribution to a greater Germany. This was the message from the Reich Propaganda Minister, Joseph Goebbels, but to most of the youth of Germany it just seemed to be the right thing to do. In practice, especially after the war came, the BDM girls’ service to the Reich could be different from what they were told, and many girls were used as common maids for higher ranking local members of the party.

Even before the outbreak of war, the BDM began including programs that were oriented more toward the traditional roles of women. The Glaube und Schönheit (Belief and Beauty) Society was founded in 1939 as part of the BDM and was dedicated to preparing young girls for domestic and child care futures.

As part of Frieda’s year of service, which began that year, she worked for a Nazi official in town named Herr Hormes. She was basically a servant to the family, responsible for cleaning the house and doing some cooking. She spent days at the house but went home to her own house to eat and sleep. That way, her family could continue drawing her ration stamps for food. There were five children, four boys and a girl, in the Nazi’s family, all under eight years of age.

Frieda’s service continued until she was severely disciplined one day for letting the fire in the cookstove go out. Her father did not appreciate his daughter being treated like a common maid and told her she did not have to go back to work there—and she did not. Instead, she went to work in the local municipal office, where ration stamps were given out. Unfortunately, a family with some political pull wanted their daughter to have that job, so Frieda finished her service in a bakery, which was hard work but with obvious benefits.

In 1942, Frieda’s mother became ill with a major hernia, and no doctor in the area could treat her. A trip to Nuremberg was required to see a specialist. This was a serious condition at the time, and doctors who could perform the required operation were difficult to find. The Nuremberg specialist called in several doctors to observe the delicate operation, which was a success, but it was a frightening time for 14-year-old Frieda. It was several weeks before her mother was able to do her normal housework, and that put a strain on everyone who depended on her.

In late 1944, Frieda worked as a seamstress in her hometown, and this continued until mid-March 1945, when the Americans bombed the place. She was taking a break at the time and had gone outside for some fresh air. She saw the airplanes overhead but did not think much of it until someone told her they were American planes and that she should get inside. She went inside and down into the cellar just as the bombing began.

The bombs wrecked the sewing plant. One unexploded bomb lodged in the wall of an adjoining building and remained there for years after the war. The only real casualties of the bombing that day were several horses. There were other bombing raids in the immediate area, and there was no public shelter nearby. Frieda’s house, however, like most of that time, had a large cellar used for protection. The biggest danger from the sky came from the machine guns of German fighter planes over the town. Most houses had bullet holes in their roofs by the end of the war.

Annemarie’s former husband was a prisoner of war in Russia, and although they were divorced she still talked about him. She also told Frieda stories about her biological father, who had been a machine gunner in World War I and was bayoneted twice in the back during a retreat from France. He recovered in a French hospital and worked on a farm until the war was over. He spoke French well and was rumored to have enjoyed the company of the French ladies.

Annemarie was later married to Fritz Merklein for a short time, and they had a son named Dieter who died of diphtheria at less than a year old on the day American soldiers occupied their town. They tried to get doctors in the area to see the child, but they all had been drafted into the military. The state-appointed doctor for their town told the family that all the child needed was fresh air out in the country. They knew better. The boy just kept getting weaker and would not eat.

One day, Annemarie happened to see from her upstairs window one of the local doctors walking by. She ran down and caught up with him and got him to come and look at the boy. He told her to take the child to Nuremberg immediately, which she did. The boy seemed to get a little better after the treatment and managed to eat a little, but one night he cried out, stood up in his bed, grabbed onto the railings, and shook them as hard as he could. They all knew he was dying, but he was fighting death as hard as his weak little body could. He died the next day.

Everyone in the town had been warned about the approaching Americans. German soldiers continued to march through the town, but they were not staying. They were on their way east to fight the Russians. The townspeople had been told for months that the invading Americans would rape and plunder, but when they finally did arrive it was a different story. The Americans came on April 14, 1945, and found no resistance in the town, so there was no real fighting. All of the able-bodied men had already been drafted.

Because Frieda’s family had a large house, it was commandeered by the soldiers as their command post. The family had to get out, but they were allowed back to collect personal things and supplies. The Americans were, for the most part, a well-behaved group, and Frieda, being a pretty 17-year-old girl, was never without a dance partner. There were official rules against fraternization, but they were not strictly enforced.

A few American soldiers were ordered to remain behind to keep control of the town after the majority of them moved on, and they stayed in the Streit house as well. Frieda really did not remember the day the war ended. It ended for her and her family when the Americans came. She did remember the endless stream of refugees coming from the East, trying to escape the advancing Red Army. Among them were relatives of her future husband, from Annaberg in the Ore Mountains.

Near the end of the war, the boys in the Hitler Youth were called to an active role in the final defense of Germany. The BDM rarely took part in the actual fighting but did help with digging antitank ditches to defend towns against the invading enemy. That was mostly far to the east and west of Frieda’s hometown. It was suggested that the BDM be instructed in the use of weapons for self-defense, and many girls were anxious to learn.

Some girls even joined Hitler Youth battalions, mostly fighting the Russians, because they had been told of the atrocities committed against German women in the East. The Hitler Youth (including the Bund Deutscher Mädel), the largest youth organization ever known, was declared illegal by the Allies and disbanded soon after the war. Schirach received a 20-year sentence at the Nuremberg war crimes trials and served the entire term.

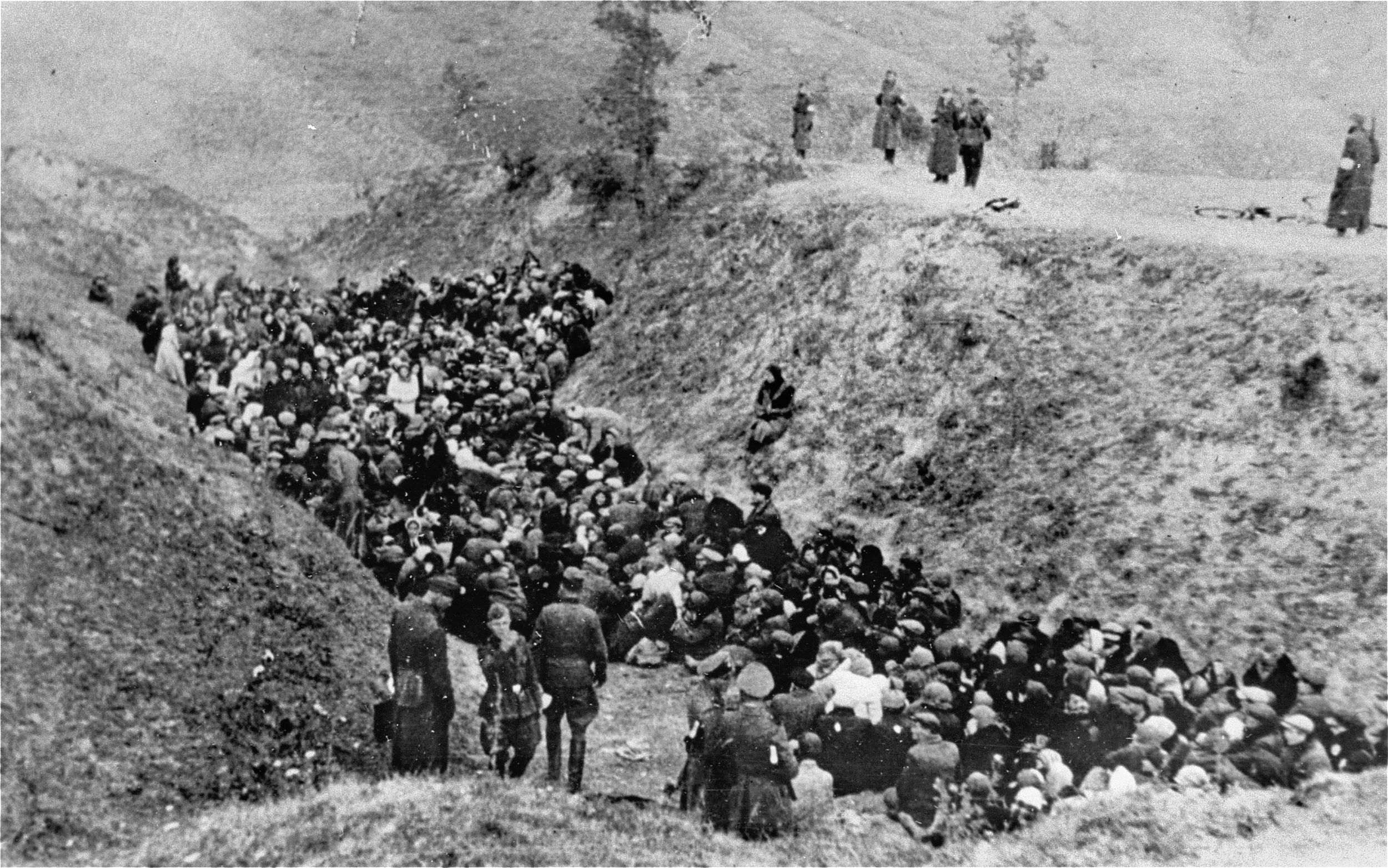

Frieda did not know about the concentration camps until after the war or at least near the end. She did hear stories of a woman whose husband (a German) was put in one, probably Dachau, and that the woman herself was later put there too, but they both survived the war. After the war, their downstairs neighbor was removed from his job because he had been a party member.

Frieda’s father had been a train engineer during the war and was too old to be drafted, but he had to join the party. He did not want to, but his supervisor told him, “Streit, if you want to see your family eat, you’d better join,” so he did. He was also an amateur photographer and radio repairman, so it was easy for him to find work with the Americans after the war. He was never treated badly, even though he had been a member of the party, and he was not harassed about it after the war.

Frieda’s father had his own workshop in the house and did not tolerate the American boarders messing about in it. He was recognized as a skilled technician, and there were few of them left in Germany by that time.

Frieda was amazed at the merchandise that suddenly appeared in stores immediately after the war. The store owners had hidden everything until the end because they knew that it would have been paid for with money that would be worthless soon or confiscated for the war effort. If this hoarding had been reported to the Gestapo, it is likely that arrests would have been made.

The Americans were doing most of the buying in Ebermannstadt and all over Germany; they were the only ones with money at the time, and the Germans were all too happy to take American dollars. They knew they could be exchanged later when new money was printed or used to buy things from the Americans. It was a while before essentials like food and clothing were available, but a new washing machine was certainly available, although it was difficult to determine how much American money it should cost. These details were worked out quickly, and businesses began to function again.

On Sunday, June 20, 1948, when the new Deutschmark was introduced, everyone got 40 marks, but within a few weeks there were again millionaires in Germany. Most of them were the same millionaires that had existed long before the end of the war.

The janitor of the local Catholic Church in Ebermannstadt had a brother who everyone knew was in the SS during the war. The local people thought he had something to do with the Dachau concentration camp because it was not too far away, about four hours by train. It was suspected that he was a guard there. After the war, he came back to town to live, and he was questioned by the Americans to determine if he had committed any war crimes, but they let him go. The SS was labeled a criminal organization at the end of the war, and many of its members were arrested and put into the recently liberated concentration camps themselves.

There was one occasion when a group of Jews came to Ebermannstadt and wanted to know where this man lived. Apparently they knew him from Dachau and wanted to see him arrested, but it never happened. Frieda kept up with the trials in Nuremberg through the newspaper and kept a scrapbook of all the stories. It was the major news across Germany, and it was happening near her hometown.

After the war, Frieda worked for the Americans in Ebermannstadt, cleaning and keeping their barracks in order and later working for them in Nuremberg. She worked for an officer from Oklahoma who treated her well and paid her in food and coffee. This also gave Frieda a chance to learn about America; the soldiers talked about home all the time, and it sounded like a pretty good place to live. At the time, Germany was no place for a young woman trying to get a start in life. After a while it seemed like she already knew something about the places she wanted to see someday.

Oklahoma sounded very different from Germany, with so much open space and no mountains, but she also learned that there were plenty of mountains in other parts of the United States. It seemed that whatever kind of place someone liked could be found in that big country. Frieda thought that she would like to visit this place that everyone seemed to love and find out for herself what they were all talking about. The problem was that she had no money.

It was not too difficult to get a visa to America, especially if one had relatives there, but travel was expensive. The Allies printed new money, but it was just as hard to get as the old had been years ago. There were jobs that paid well, but they were mostly for men able to help with reconstruction, and food was scarce for a while at any price. Money earned in Frieda’s family went toward buying the essentials, not toward travel to America.

In 1953, Frieda borrowed money from Annemarie’s second husband to travel to America. She did not like this man much, but he did have money. This was money it would take her a long time to pay back. Annemarie and her husband had been in the United States a year already, in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Frieda also had uncles in the United States. Everyone threw Frieda a good-bye party before she left, and they took lots of pictures. Her parents remained in the same house in Ebermannstadt as long as they were able to care for themselves. The house has long since been torn down, and today it is a parking lot for the local post office.

Annmarie and her husband left Oak Ridge and moved to Florida shortly after Frieda arrived. The couple divorced soon after that.

Frieda’s first job in America was as a housekeeper for a man in Oak Ridge. It was a good job, but it did not pay much, and she saved everything she could to make payments on her debt. One day while she was out, a man named Herrmann called on the phone for her. She was given the message that a man with a German accent had called. She did not think too much of it until he called back again and she was able to talk to him. His name was Ernst Gerhard Herrmann, but he went by Gerhard. They talked several times, and she became friends with him.

Gerhard was well established in America and had become a machinist, but then she heard that he had told someone that he thought she was too young for him. Well, Frieda thought, if he thinks I am too young for him, then maybe he is too old for me. Eventually Gerhard persuaded her to take a trip with him to the Great Smoky Mountains. He did not know that she would invite the family she worked for—it was the right thing to do, after all.

The group visited the park, but their picnic was interrupted by bears that forced them back into their car. After the trip, Gerhard told Frieda that he was planning a visit to Germany and asked if she would like to come along. She went, and during their stay they got engaged and married on the cruise boat Italien. It was a fairy tale sort of romance. He was several years older, and he had an 11-year-old son, Hans. His first wife had died years earlier.

The marriage was a good one. As it turned out, Frieda actually married Gerhard twice during this visit. In Germany, a couple was required to publicly announce the wedding at least four weeks in advance of the ceremony, and they had not done that. They did hear that if they went to Munich they could get married legally right away. So it was off to Munich, where they were married again with her mother as one of the witnesses.

Frieda and Gerhard had one son, Frederick Thomas Herrmann, born April 6, 1955, in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. He now lives in Huntsville, Alabama. Hans Herrmann lives in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Frieda, Gerhard, and young Frederick made many trips back to Germany, and Frederick remembers that after one long trip he forgot how to speak English.

Frieda made a few trips back to Germany after her husband died in 1992. Frieda died in Huntsville on January 5, 2010. Her story is not unique. Thousands of young girls, most of them former BDM members, found their way to the United States after the war, but their stories are rarely told.

Author Don A. Gregory conducted extensive interviews with Frieda Streit Hermann for this article. He resides in Huntsville, Alabama.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments