By Tom Row with James Bilder

Overshadowed by the Mighty Eighth in England, the Fifteenth Air Force flew out of Italy and played no less important—and every bit as dangerous—a role in bombing targets in Nazi Germany and elsewhere. Flight Engineer Tom Rowe “backed into” service in the Army Air Corps’ Fifteenth Air Force but went on to complete 25 missions, including a narrow escape from German-occupied Yugoslavia after being shot down. Here is his story as he tells it:

A Family Man Goes to War

The attack on Pearl Harbor had galvanized the country. Whatever feelings we had about the war before December 7, 1941, were now all replaced by a desire for victory. I went down to the Naval Recruitment Center on December 8. The Navy seemed like the logical choice since my brother-in-law was serving on the destroyer USS Winslow.

I had married in 1936, and my wife and I had two daughters. The U.S. Navy recruiter saw my 3-A rating from the draft board and simply said to me, “Go home and take care of your family.”

I was working then as a bellman at the Palmer House Hotel in Chicago. It seemed by 1942 that everyone was in uniform. I kept getting questions from patrons like, “How come you’re not in service?” and “My boy’s in uniform—why aren’t you?” This began to weigh heavily on me, and I started drinking. Finally, my wife Marion said to me in the late summer of 1942, “If it means that much to you, go down and enlist!”

I passed my physical and was sent to Camp Grant in Rockford, Illinois, for induction and processing. I spent two or three days there before being sent to Kessler Air Base in Biloxi, Mississippi, for 10 weeks of basic training. Someone had told me that paratroopers earned extra pay so, as a married man, I thought that would be best for my family. When I completed basic training, I told my superiors that I wanted to be a paratrooper, and they said that was fine.

Never Prime a Hot Engine

After congratulating us for finishing basic, we were all told to put on our overcoats and board a train. Once on board, I discovered our destination was Lincoln Army Air Field in Nebraska; we were told that we were going to be trained to be airplane mechanics. I got up from my seat and explained to a sergeant that there must be some mistake since I was supposed to be in the paratroops. He looked at my small frame and commented, “You haven’t got enough weight to pull the cord on a parachute,” and told me to go back and sit down.

The mechanics training was engine related and at first was nothing more than high school level physics. I decided I would get into the paratroops by intentionally failing my exams. An officer called me into his office and said to me, “We know what you can do. What did you enlist for? If you fail, we’ll make you take this whole course again.” There was more than an implied threat that it would not be a pleasurable experience. I knuckled down and finished 11th in a class of approximately 300 men.

The Army Air Corps planned to make me an instructor of mechanics. We were to work on Curtiss P-40 Warhawks, Republic P-43 Lancers, and P-47 Thunderbolts, and my favorite: the Lockheed P-38 Lightning.

Once, during a preflight inspection of a P-38, I was teaching kids how to start an engine. I had my third student of the day in the cockpit while I stood on the wing leaning in to supervise. There was a civilian employee from Lockheed on the ground nearby with a large fire extinguisher. I had stressed over and over again to my students how they were never to prime a hot engine. Well, as one might expect, this student primed the engine and instantly set it on fire.

The civilian employee immediately panicked and fled, yelling, “Run! It’s gonna blow!” Everyone scattered, but I wasn’t going to leave this kid trapped in the cockpit or abandon my plane. I removed the inspection plate and stuck the hose of the small extinguisher I had into the hole and released the chemical. Thank God it put out the fire, but the engine was badly damaged. The Army rule was that if you broke it, you paid for it, so, as instructor of this class, I was the man responsible for the equipment. I thought I’d spend the rest of my life in the Army paying for this engine. Instead, I was promoted to Technician 3rd Grade (corporal) and put in charge of five mechanics. Many of these men were self-taught and knew a great deal.

The Camouflaged Factories of California

A master sergeant recommended that 14 of us be sent to the Lockheed facility in California to conduct 100-hour inspections on P-38s. It was customary during these inspections for the punch (fix) list to be compiled and then return the planes to the factory for repair. These repairs were usually minor, so we began simply making them ourselves so that the planes could be put immediately into service.

Since we weren’t near a military facility, the Army gave us coupons for meals, and the local diners and restaurants gouged us. They simply took the coupon for the meal even though the coupon was worth more than what we ordered. The Lockheed people told us to eat in their cafeteria where the prices were cheaper and they actually gave us change, in coin and currency, for the difference.

California was always fearful of an attack by the Japanese, and the factory where we worked was camouflaged, with antiaircraft guns on the corners. In fact, the Douglas Aircraft plant was camouflaged to look like a farm from the air!

By this time, I had given up on ever becoming a paratrooper, but the idea of flying intrigued me. So, I applied for the aviation cadets. My instructor took me up and noticed my gloves became wet from perspiration. His opinion was that I was too nervous to fly. My opinion was that I was simply anxious. His evaluation prevailed, and I was dropped from the program.

Gunnery School

I was then sent to an area north of Las Vegas, Nevada, for seven weeks to attend Air Corps Gunnery School for Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers. Today, this area is Nellis Air Force Base. We started out with BB guns, then we moved up to .22s, and then shotguns. You had to hit 25 out of 26 skeet targets before qualifying; I did it the first time. They put us in the back of a truck that was supposedly going 30 mph, but it felt more like 20 mph. We were moving on the ground, and so were the targets we shot at. We had to hit 18 out of 36 targets, and we all qualified.

We continued to advance to higher caliber weapons. We fired .30-caliber machine guns, then Thompsons, and finally .50-caliber machine guns. We had to strip and reassemble a .50-caliber machine gun while blindfolded and wearing gloves. We tried to keep the parts in some form of order, but the sergeants would come and mix them up on us. This was to simulate combat conditions on a plane but, believe me, there was no one alive who could perform this function on a plane in combat.

Then they took us into a room that had a 360-degree view to conduct operations simulating action in the ball and top turrets of a bomber. The .50-caliber machine guns fired red flashes of light at simulated enemy planes, and every person had to take turns in both the simulated ball and top turrets.

The Air Corps also had jeeps at 500- and 1,000-yard distances pulling red sheets. We fired .50-caliber machine guns that were mounted on a pedestal. The bullets had paint on them that clarified the holes we put into those red targets.

In actual air practice, we flew in Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses and fired at targets towed 100 yards behind North American B-25 Mitchell bombers. We also had simulated attacks where we flew in formation and our cadet crews were attacked by cadet fighter pilots. One overzealous pilot flew right in between our formation, which was both dangerous and reckless. Our guns had nothing more than cameras on them, and I was called out more than once for continuing to fire on my target long after I had successfully destroyed it. I flew on training missions manning the top turret and the waist gun of a B-17. I was promoted to tech sergeant and told that I would be assigned as the flight engineer of whatever crew I ended up with.

Saxby the Gambler

At the base, I was the barracks chief. In my barracks there was a guy named Saxby, who was quite a character. In civilian life he had been a card dealer in a syndicate gambling joint in Detroit, and then a staff sergeant and cook in the Air Corps. He was made a mess chief but got caught bootlegging and drew a seven-year sentence in the prison at Fort Leavenworth. The Army told him that they would clear his record if he went to gunnery school, so he accepted.

In the morning, Saxby wanted to sleep in, so I would cover for him at morning roll call and announce, “All present and accounted for.” He even missed breakfast most mornings. Someone arrived late one morning to PT and the sergeant announced he was going to deny everyone’s weekend pass as a result. Saxby was small but had used his time in prison to really build himself up. He challenged the sergeant, saying that the passes should only be denied if the sergeant could outdo him in chin-ups. The sergeant accepted, thinking he would easily best Saxby.

Saxby did them overhand rather than underhand and quickly outdistanced the sergeant, who was now obligated to issue everyone their weekend passes. Six of us went into Las Vegas to El Rancho Vegas, which was the city’s best nightclub at the time.

We were watching a blackjack game when Saxby informed us it was crooked. “They’re using diamondback readers,” he told us. “I can read those cards better than they can,” he said. We established a set of signals and sat down at the table. Saxby sat closest to the dealer so that his hand would be the last one played.

We were betting $5.00 a hand while Saxby bet only 50 cents. He would signal us as to whether or not to take the hit. He would also foul up the dealer by taking a hit even when he didn’t need it. The pit boss caught on to us and closed the table. Since we were military personnel, they couldn’t give us any trouble. Once outside, we split $300 in winnings between the six of us.

Training For B-24s

We all assumed we would get furloughs after we finished gunnery school. Instead, the Air Corps sent us to Mountain Home, Idaho. I can only describe it as Tobacco Road with a Coke machine. We spent a month there doing a little more testing, training, and processing. Then they told us we were headed for Gowen Airfield in Boise.

Most of us had had enough, and I went with a friend to see our commanding officer. We politely but firmly informed him that if we didn’t get furloughs, the entire outfit would go AWOL. It was a bluff; the other guys in the outfit had chickened out, but we got the CO’s attention. When we lined up to get our pay; there were MPs and buses with their motors running, waiting for us. When we arrived at Gowen, there were MPs waiting for us there, too. We were brought into a large hall where the CO apologized for not being able to issue us furloughs, but he promised after we completed our classes that we would get leave.

“To show I trust you,” he said, “you’re all going to get Class A passes.” There was good food in the mess hall and a dance band playing, but no women present.

I had to learn everything about B-24s. Since I would be there for roughly three months, I had my wife and two daughters come out and stay in Boise for almost 10 weeks.

Our crew formed up. Our pilot was 2nd Lt. Robert Crinkley, 2nd Lt. James Owens was co-pilot, 2nd Lt. Francis Deans was bombardier, Rufus Breland was the nose gunner, and Walter “Shorty” Wright was the ball-turret gunner. He had been in Clark Gable’s gunnery class. Edwin Hand was the top turret gunner, James Shipman the tail gunner, Wilbur Penno the radio operator and right waist gunner, and I was the flight engineer and left waist gunner. We did not yet have a navigator. Every day, we flew four hours and had four hours of classroom instruction. It was grueling, but we were all up to it.

After about two weeks, a second lieutenant named Nate Berliner joined our crew as navigator. Deans, our bombardier, had been doing the job for us until this time, but Berliner soon proved his worth. We got lost one night over Cheyenne, Wyoming, due to heavy clouds; Berliner did an outstanding job of getting us back quickly on the proper heading. After that, there was never any doubt in our group about his ability to navigate.

Berliner was an especially interesting individual. Before the war, he studied to be a brewmaster in both France and Germany. He was working for a brewery making an incredible $25,000 a year when he got drafted.

Even training stateside had its share of risk. During one training mission, we had engine trouble and had to land in Clovis, New Mexico, where we spent the night while an engine was replaced. Back then people still rode horses, and Indians slept outside wrapped in blankets. I felt like I was visiting the Wild West of yesteryear.

Another time we were making our approach to land. As the flight engineer, I stood between the pilot and co-pilot calling out air speeds. The regulation landing speed was 127 mph. All of a sudden the left wing tipped and the pilot called out, “Hard right rudder!” We started to stall, and I found out later that the instructor pilot in the plane behind us told his students, “They’re going to crash, they’re caught in prop wash.” But our pilot regained control and brought the plane around for another approach. “I knew we’d be OK,” I said after we landed.

Off to Italy

Our training now completed, it was time for Marion and the kids to return home. It was all right because we all got 10-day passes so we could go home before reporting to Topeka Army Airfield.

On our scheduled arrival day in Topeka, everyone had to report by noon. I was early and met our radio operator. We decided to visit a nearby bar before reporting. Almost immediately after our arrival, a fight broke out. Someone threw a full beer bottle and hit the poor girl sitting next to me right in the forehead. She was knocked out cold, and we dragged her out the back door. Army MPs were right outside the door and ready to go in just as we were coming out. They were about to arrest us when a friend of the girl we were helping explained what had happened.

At Topeka, we were told that in three days we would be leaving for Italy. Half the crews would fly over, and half would go by ship. The pilots drew lots, and our pilot got us stuck on a boat. We took a train to Norfolk and waited two days for our boat. Our transportation overseas was via a Liberty ship, the SS Joseph Gale. We traveled in a convoy, and the journey took 23 days; there were 350 men living in our cargo hold. We got one shower a week with salt water, which didn’t fully rinse the soap off and it dried like glue in our hair. We shaved our heads.

We arrived at the port of Naples in August 1944. Our Liberty ship’s personnel claimed that the debris we saw floating in the harbor was from a recently sunk enemy sub. We never did find out whether it was true, but it impressed upon us that this was real war and we were now where the action was. Everybody grabbed two duffle bags at random as we left the ship. I had the misfortune to grab a bag that belonged to a guy who lifted weights.

At the railroad station we saw rails all coiled up, bombed-out buildings, and a lot of other war damage. The civilians were in lines waiting for soup and bread. Our train took us across Italy to our new home—Torretta Field at Cerignola. On October 17 we were designated Crew #6233 and assigned to the 767th Squadron of the 461st Bombardment Group, Fifteenth Air Force. We would be flying B-24 Liberators on missions over southern and central Europe—mostly Germany.

The First Three Missions

The first thing we were told upon arrival was that we could expect tough going and that all of us should consider ourselves dead already. They separated the officers from the enlisted men, and we were told to put up our tent, which would be shared by six enlisted men. None of us had been trained how to put up such a tent and, during a rain storm that night, all the tents collapsed. We were able to get plywood and used the tents as roofs. We also dug slit trenches outside our canvas abodes for shelter during air raids.

We had an instructor pilot who flew in 2nd Lt. James Owens’s co-pilot position during our first combat mission. There were problems with our number one engine and the supercharger wouldn’t work. We were falling back and the instructor said it was the flight engineer’s job to fix the problem. I pulled out the amplifier and put in a spare fuse, but that blew too. So did all the other fuses I put in. Finally, I used the foil paper from a pack of cigarettes to run a bypass. But by then we had fallen too far back and were ordered to abort the mission.

We had our own crew for our second mission. There were no enemy fighters, and the antiaircraft fire was inaccurate. I remember thinking, “This ain’t so bad.” My thinking was reinforced after our third mission, which was a real “milk run.”

A Hard Bombing Run

It was our fourth mission that turned out to be the thing of which nightmares are made. On November 20, 1944, our mission was to bomb the south plant of the synthetic oil refinery in Blechhammer, Germany. This was the fifth time that this target was to be hit by our group, and during the pre-mission briefing you could hear guys groaning when they heard what the target was.

This time the mission was highly successful, as it was the first time that winds had prevented the Germans from obscuring our targets with smoke. Twenty-three of the 26 planes in our group took flak hits—and we were one of them. We got hit during the bomb run and the bomb bay doors wouldn’t close. Then Deans, our bombardier, yelled, “I’ve been hit.”

I was ordered to go down and close the bomb bay doors manually, using a crank. On my way down, I looked into the nose of the plane and saw the entire floor covered in red. All I could think was, “Oh, geez, poor Deans.” The smell of cordite (smokeless powder) from the German AA rounds permeated everything.

I wore no parachute as I stood in the bomb bay area cranking those doors shut. I could see the ground far below and was thinking that I was going to be nothing more than a grease spot and my family would never know what had become of me.

I let Lieutenant Crinkley know that I had closed the doors, and he told me to go and help Deans. I went into the nose and saw that Breland, our nose gunner, was hit as well. “Take care of Deans,” he said. “He’s hit worse.” Breland was wrong but didn’t know it yet. He had been hit by something between his eyes that had exited through his mouth. I told Deans that he would have to help, so he used his feet to push himself as I pulled him under his arms.

I got Deans out of the nose, and we cut his pants open to see the wound. He had been grazed in the hip, and it was nothing more than a deep scratch. The red liquid all over the floor of the plane’s nose was hydraulic fluid!

I went back for Breland, and he said to me, “You’ve been hit; there’s blood on your shoe.” I cut my pants leg open, and there was a jagged piece of shrapnel sticking out of my right shin. The blood made it too slippery to pull out with my hand, so I took out a pair of pliers from my pocket and used that.

Bailing Out Over Yugoslavia

In all the confusion over the target, the squadron leader made a wrong turn after our bomb run. We were soon separated from our group and lost in the clouds. There was no visibility, and Crinkley asked us if we wanted to fly blind to the south or southeast or drop down and get a fix on our position and risk being seen by the enemy. We opted to drop down. Within five minutes, Berliner knew where we were.

We stayed low, and 20 minutes later we heard a big bang as the Germans opened up on us again. A round had gone through the bomb bay and hit the wing; then Shipman reported that our tail was busted up. Our plane was low on fuel and full of holes. We were now over Yugoslavia, and Crinkley told everyone to get their chutes on; he would hold the plane steady while everyone bailed out.

One by one everyone jumped. Shorty waved to me before he bailed out, and soon it was just the pilot and me. I tried to jump out but couldn’t; I ended up falling out and was turning summersaults in mid-air. I was thrilled to be out and didn’t hesitate to pull the ripcord. I held onto that ring tightly and didn’t let go, even after the chute had opened.

We had British parachutes, which were better than our American ones. I saw the slits in the panels (there to help with navigation) and mistakenly thought I had a defective chute. I was also coming down backwards. I saw a lake and sure as hell didn’t want to land in that, so I pulled the shroud lines (thank God for those slits) and managed to steer clear of the water. I could see a stone fence coming up under my feet and was happy when I thought I cleared it, but it angled around and I cracked my tailbone when I slammed into another section of it.

From the air I had estimated the wall’s height at around eight feet, but in reality it was only two. Still, that was tall enough to give me one hell of a jolt. Sore, I got up and situated myself. Standard operating procedure was to bury our chutes, but all I had was a trench knife, and I couldn’t dig with that. So, I threw my stuff into some foliage. I walked on and came across Deans hanging in a tree. I told him to get down right away. “No,” he said, “I’ll fall.” I looked at him and said, “You’re only a foot off the ground!”

“Amer-ican-sky! Amer-ican-sky!”

We knew the Germans would be looking for us, and we heard movement. We moved south by southeast and eventually met up with Penno and Shorty. The procedure was to travel in pairs, so the four of us would have to split up. Penno could speak German, so I wanted to go with him. Besides, neither Shorty nor Deans drank, so I figured they would make a good pair.

The escape kits we carried were supposed to have food for several days, but, even eating very sparingly, they only lasted for a day. We had canteens but no water, so we used snow.

On the third day, we went up a plateau that had bushes on each side. It seemed safe enough. We soon saw a guy in uniform come running at us with a rifle and bayonet. We first thought he was a German, but as he got closer we saw that his uniform looked more like something from a military school as opposed to that of an infantryman. Also, he had a red star on his cap. “Amer-ican-sky! Amer-ican-sky!” we yelled, as we pointed to the flags on our shoulders. Our captor was a 17-year-old Yugoslav partisan who immediately began to smile and wave his arms. About 25 other men then burst from the brush and promptly began to hug us and kiss our cheeks.

This partisan group was led by a little red-haired guy who spoke English with an American accent; he told me that he was from Brooklyn. He had been visiting his grandparents when Yugoslavia was invaded, and the Germans wouldn’t let him leave. He led this group with such professionalism and skill that I have always suspected he was really an OSS agent.

We were taken to a farmhouse, and there were Deans and Shorty; the partisans had already picked them up. Berliner showed up next; his chute had not fully opened, and he was busted up rather badly. One by one, nearly our entire crew was reunited.

Deans and Shorty had been drinking what I thought was water. I was partially dehydrated and when they handed me a glass I took four big gulps before I realized it was vodka! We were famished and they gave us the only things they had available: anchovies with black bread and butter. Shorty couldn’t get the butter off the roof of his mouth and he threw up.

Meeting Tito

They kept us in the farmhouse until dark, when a truck showed up. They told us that they were going to take us down to Zara (Zadar) on the Adriatic Coast in Croatia; it was currently occupied by British commandos.

We were concerned about German patrols, but the partisans assured us that the Germans never came out after dark; at night the countryside belonged to the partisans. The truck kept its lights off as it drove over dangerous mountain roads. We were concerned, but again the partisans reassured us as they explained that they knew every inch of the territory we were traveling over.

We passed Zagreb, the country’s second-largest city, and everything was going well. Then we saw a lantern light in the middle of the road being waved from side to side. The truck stopped abruptly, and we all held our breath. A bayonet on the end of a rifle came between the curtains on the back of the truck and pushed a curtain to one side. We breathed a sigh of relief when we saw it was a partisan.

In Zara, we saw land mines stacked up along the roadside. We were then taken into a church and brought to a British colonel who said, “We’ll get you Yanks back to your unit. While you’re here, do you want to meet Tito?” Josip Broz, better known as the communist Yugoslav guerrilla leader Marshal Tito, was famous even then, so we were excited at the chance to meet a celebrity.

Tito was wearing a black suit with a white shirt and tie and had four aides with him. He asked, “Did you bomb Berlin?” We were explaining our actual target when the colonel told us that was all the English Tito spoke.

Escape From Yugoslavia

The British later told us they had a gunboat that would take us back to Italy, but it looked like nothing more than an undersized yacht. Its challenge gun was very small, and its other guns were only .30-caliber machine guns. We were at the dock when the British crew was told to be careful of an Italian cruiser, now in German hands, that was sinking Allied boats in these waters. We boarded and hoped for the best.

In the middle of the night, alarms and sirens started to go off, and the British went to battle stations. In the distance we could see a light atop a larger ship that shined down directly on our little craft, and I thought, “Oh no, we made it through all this and now these damn fool Brits are going to fight it out with a cruiser and get us all killed.” But signal lights started sending messages back and forth between the two ships, and it turned out that this particular ship was a British cruiser searching for the enemy cruiser.

The next morning the British gave us a breakfast of stewed tomatoes and bread. They offered what I thought was tea and, since I didn’t like tea, I declined. My comrades asked me why I refused a drink and, after they informed me that it wasn’t tea but rum, I ran after that Brit to get my share.

In Italy, we arrived at the port city of Ancona. The British flew Vickers Wellington bombers out of there, and we were surprised to see that their runways were not paved. Inside their quarters, they had a bar and sofas—even a waiter!

I asked one member of a British aircrew how many missions he had flown on. He said, “Yank, we don’t go by missions. We’re here for the duration.” I found out later that this was untrue. I also learned that the British had sergeants in charge of planes, which surprised us since in the American Air Corps only officers could fly.

A Gas Leak?

An American Douglas C-47 transport plane picked us up and flew us to Bari, the headquarters of the Fifteenth Air Force. The shrapnel wound in my right shin had become infected, and it was worrying me a little but the doctors treated it successfully and I was sent back to duty.

Now back in Italy, we were reunited with Sergeant Breland, the wounded nose-gunner, and Lieutenant Crinkley. Crinkley had been badly injured in the jump and would require a lot of recovery time, so our crew would need a new pilot. Penno and I went to see our commanding officer, Major Frank Poole, to recommend Crinkley for the Distinguished Flying Cross. The major told us, “An enlisted man can’t recommend an officer for a decoration but go ahead—what’s your story?” We told him how Lieutenant Crinkley had kept the plane steady as every one of us bailed out. “He did his job,” Poole answered. “So did you.” That was that.

A few days later, Major Poole said that he had a potential replacement in a newly arrived pilot. The major said he would fly along as co-pilot on a practice flight. The flight went along all right, but we bounced on our landing. The major had given me veto power over this choice, and I exercised it. Our crew was then broken up.

Those flying on missions had to be awakened at 4:30 am for preflight briefing. Men assigned a mission put a towel on the end of their bed so people knew who to awaken. We also had to be clean shaven so that our oxygen masks fit properly. This day, December 19, 1944, I saw that Shorty’s hands were shaking. He looked at me and I asked, “Do you want me to fly for you?” He nodded.

The pilot for that mission was Lieutenant Robert Roemer. I think we were to bomb yet again the south oil refinery in Blechhammer. After we took off, I climbed into the ball turret in Shorty’s place and saw fuel coming from our wing. I called the pilot and reported, “We’ve got a gas leak.” The flight engineer looked out and said, “No, we’re siphoning,” then told the pilot I was “just nervous ’cause he got shot down.”

But aviation fuel had a blue dye in it to make it visible, and I knew what I was seeing. “I may be nervous,” I replied, “but that’s still a fuel leak.” The captain sided with his flight engineer, so I told him again, but this time on the interphone so the entire crew could hear. Then I used the interphone to tell the guys in the waist to put on their chutes. Lieutenant Roemer came back to have a look and told the captain to abort the mission.

When he got back to base, the colonel in the control tower came out with Major Poole. They were mad as hell, and our flight engineer was quick to point out to them that this was my call, implying he didn’t agree with it. The officers made it clear that I had better be right about this. They asked me why I was so certain that there was a fuel leak. I explained that siphoning runoff comes from the fuel tanks, not the edge of the wing.

We all waited while an air inspector came out and examined the wing. Sure enough, a clamp had come loose from a hose on a fuel cell; we had indeed been leaking fuel. The colonel and major simply walked away satisfied with my work. Lieutenant Roemer asked me to fly with him on a regular basis, and I agreed.

Taking Flak Over Austria

We were sent up the next day to bomb the synthetic oil refinery at Brux, Czechoslovakia. The weather was so bad over Yugoslavia that we got orders to hit a secondary target at Linz, Austria, along with the 484th Bomb Group.

I wanted to see the target as it was bombed and had my face pressed against the Plexiglas window. Suddenly, an antiaircraft shell went off and shattered the window. I had shrapnel wounds in my leg, arm, and head. The wounds to my head and arm were relatively minor, but I reached down and felt a hole in my leg.

Our waist gunner had been the head of a garment workers’ union back home and could have been an officer. He refused to become an officer so that he could work on an even level with his fellow proletariats. He was also Jewish and wanted to do something that allowed for more direct conflict (like firing a machine gun) against the enemy.

He stood there in shock just looking at me while I lay on the floor yelling for him to get me the first aid kit. I pulled the small piece of shrapnel from the side of my head with my bare hands. I was still without the first aid kit when the pilot announced that we were going to go around again to line up for another bomb run against our target. We hit the target without further incident, and someone got me the first aid kit.

As we approached our base, I saw the red flares going off, signaling that there were wounded [me] aboard our plane. I had seen wounded airmen being carried on litters out through the windows of a plane, and now it was my turn. They set me down outside the plane under its wing. A doctor gave me a shot of whiskey, but I was disappointed that I didn’t get the traditional doughnut and coffee.

I was taken to the dispensary where the doctor picked up a long steel probe and said, “Now this is gonna hurt.” He inserted it into the wound in my leg to see if there was anything else in there. It didn’t hurt as much as I thought it would. The doctor removed the couple of small pieces I had in my right arm, and I was then sent to the 26th Field Hospital in Bari.

I was ambulatory a day or two later, and the doctor took me to the NCO club. We had cherry brandy with grapefruit juice and Spam sandwiches. This was my second hospitalization for a wound, but I was still denied any opportunity of going home. I used my artistic skills to draw pictures for the nurses, and they doctored my chart to say that I had a fever and could not be discharged. The head nurse caught on and sent me back to my unit.

Flying With Major Frank Poole

I had only completed six missions and had been wounded twice. The night before my next mission, I was plagued by nightmares, but the mission went off OK. I could feel a bad case of nerves coming on and went to see a doctor about getting myself grounded. He told me to “go over to the chaplain and get your TS card punched.”

The chaplain took me over to see the major and the flight surgeon. They knew I had trouble sleeping and asked me about it. The major told me that he would know that I was not sane if I wasn’t afraid—like something out of Catch-22. “We’re all afraid,” he said. Then Lieutenant Roemer made me an offer I couldn’t refuse—to fly with him and the major on their next mission.

On that mission, we were approaching our target on the bomb run and the major, who usually chose to forego wearing a helmet and flak jacket, decided to put them on this time. The flak was very heavy, and there was a minor fire in the bomb bay. This in and of itself wouldn’t have been too bad, but there was also a fuel leak. I was ready to jump without orders and leave them if necessary, but I scrambled and used the spent shell casings from two .50-caliber rounds on the floor to plug the leaks.

I had fuel on my flight suit, and the major told me to go and lie down on the floor. He told me not to use my earphones, lest a spark ignite me. He brought the plane down low, and I was able to take off my suit and throw it into a flight bag. I sat down and pouted.

The flight engineer is supposed to be the last person off the plane, but as soon as we landed, I was the first person off and the first to get on the truck. “That’s it!” I thought to myself. “They can court-martial me. I’m not going back up again.”

The major knew I was upset. He said to me, “Kid, I can’t ground you. You did your job. How would you like to be my engineer?” The major exuded confidence, and I just knew he was going to come through this war all right. I accepted, and he was right. The remaining missions were without serious incident, and I reached a total of 25 completed missions. Our activities ended a month before V-E Day.

Managing a Stockade of Prisoners

We were playing cards and had open liquor in our quarters. The major came in and saw this. For a moment, we thought there was going to be big trouble. Then he asked what the stakes were. “Dollar ante, half-the-pot limit,” we told him. “I’m going back to my tent and get my money—and a bottle,” he said.

With no missions being flown, the Army had to keep us busy, and the major had come to see me about taking a new detail. There was no way I would ever turn down a request from this man. The colonel had sent the major to ask me about running our stockade for American military prisoners. “Sir,” I said, “we don’t have a stockade.” However, I was told that I would soon have about 125 prisoners and that they would build it. I was honest with the prisoners and told them that I had never even seen a stockade. The prisoners went ahead and designed it and then built it.

When V-E Day arrived, I overheard the lieutenant who was the officer of the guards say that he was sorry to see the war end, as the war was responsible for the most money he had ever made. He had previously been in the coastal artillery but relished overseeing the stockade for its black market operations.

On rations day, we got three bottles of beer, Coca Cola, soap, candy, and the like, but the prisoners got nothing. I went to the colonel to ask about them. He thought I was goofy at first, but he acquiesced and said they could have rations, “but no beer!” The prisoners were allowed to write one postcard a week and one letter a month. They were also allowed reading material.

I went to the colonel to ask if my prisoners could go to the USO show, and he said to me, “What are you running? A country club?” He relented and told me I could take the men but, if even one got out, I would have to finish his sentence. “How do you like that?” he asked. “Sir,” I answered, “I’ll take my prisoners.”

The show was standard USO stuff until the end, when the entertainment officer had arranged for an Italian girl to perform a striptease. Men went wild, but my prisoners stayed in order and conducted themselves as gentlemen; they were the only men there who behaved themselves. Afterward, the colonel said to me, “I wish my officers behaved that well.”

indicates that the Fifteenth Air Force’s attack on the German-controlled oil-production facilities at Ploesti, Romania, May 1944, is successful. Ploesti was bombed 22 times by the Fifteenth Air Force.

The prisoners were allowed one shower a week. I got the colonel first to approve showers every three days and then on a daily basis. He even approved my request to let them have their ration of beer. I never had a single prisoner give me a problem. When we got orders to go home, I asked about the prisoners but that, I was told, was left to our commanding general to decide.

Mistaken as a POW

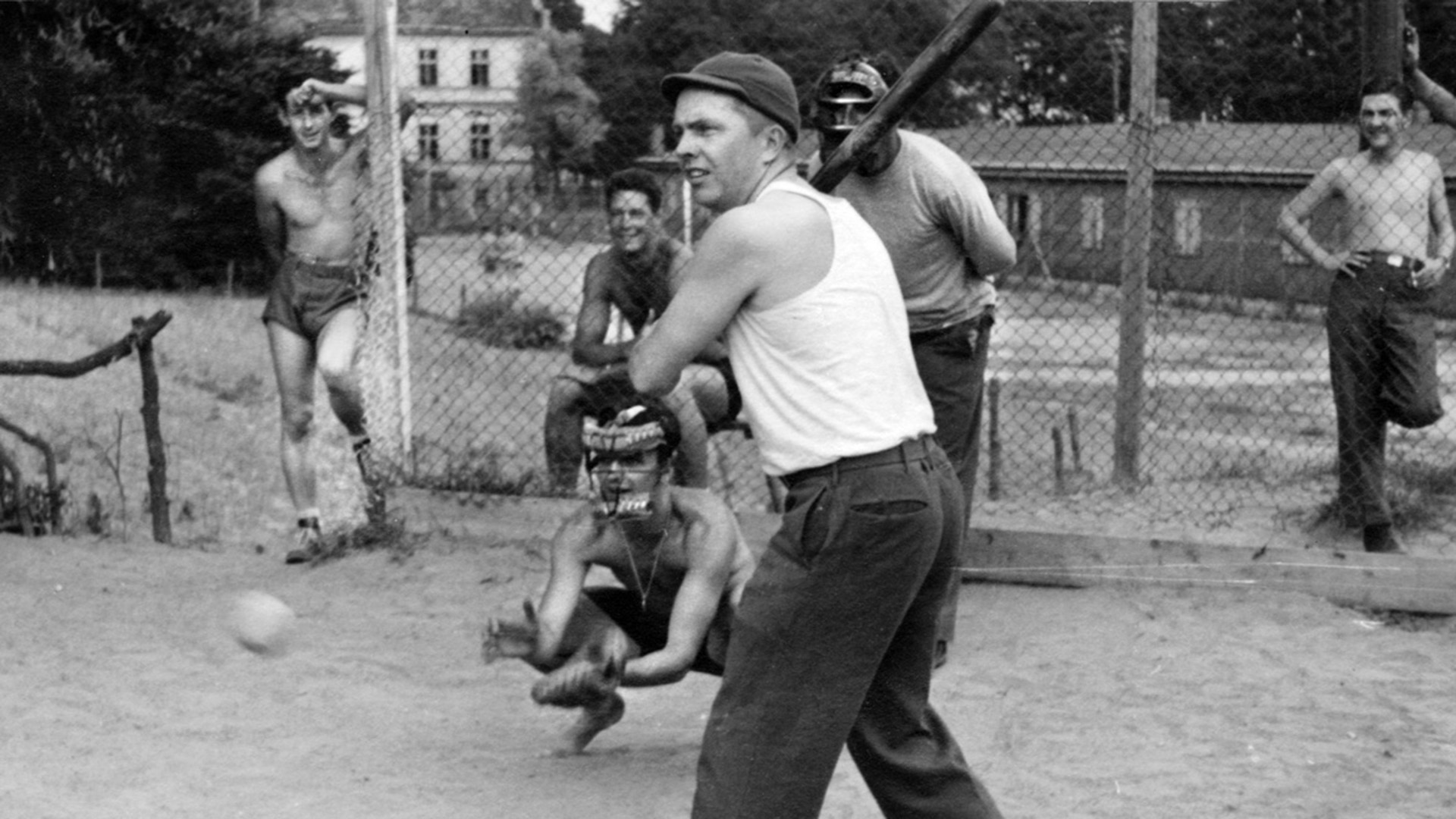

I was going to fly home with the major, but he busted his leg sliding into second base in a softball game. Instead, I flew home with a lieutenant. When I arrived in the United States, I was surprised to learn that I was classified as a POW for having been shot down behind enemy lines. I had 81 days of furlough coming, and I was anxious to get discharged. Instead, I had to report to Miami Beach to be a part of Project R. This was an FBI project to discover and report war crimes against POWs. I tried to explain that I had never been in enemy captivity, but that got me nowhere.

I was sent to the Air Corps Personnel Displacement Center in San Antonio, Texas. Even though the Army provided housing, I couldn’t bring my wife and daughters down since the girls were in school. I had to wait seven weeks before I finally got a five-minute interview with an FBI agent. As soon as I told him what had happened, he said that I should never had been there in the first place and that I could leave. Go figure! I was discharged two days later. It was in November 1945.

Enjoyed your article. Interesting parallels to my Dad service.

My Dad was a B-24 navigator in the 464th Bomb Group, 15th Air Force and also trained trained at Mountain Home, Idaho and Gowen Airfield in Boise.

He and his crew flew to Tunisia for more training via Miami, Trinidad, Brazil and Morocco. He began flying missions out of Gioia del Colle AAB, Italy while Pantanella AAB, Italy was being finished by the Cee Bees. The English had bombed it when the Germans previously occupied it.

On 5/29/44, he departed Gioia del Colle to bomb the Amme-Luther-Sec Aircraft Components factory in Neunkirchen, Austria. On the return leg, he was shot down by Me-109s south of Zagreb, Yugoslavia and landed ~2 miles W of Bosanski Novi, Yugoslavia. The entire crew bailed out and all survived. Four were captured by Germans. My Dad and 5 others were smuggled out of Yugoslavia by Tito’s Partizans. After landing he was pursued by soldiers, who he presumed were German. He came face-to-face with a soldier in a uniform wearing a cap with a red star. Pointing his gun at my dad, he asked, “Gerimano?” to which my dad replied, “No, Americano”. The soldier grinned, put down his gun and motioned Dad to follow him. A network of Tito’s soldiers and other resistance fighters guided he & his 5 crew mates between houses over ten days. A C-47 landed in a hastily-made grass field at midnight and flew them to Bari, as in your story. The 464th had moved from Gioia del Colle to Pantanella while he was MIA. He was assigned to another squadron in the 464th to finish out his 50 missions. Do you know why the 15th AAF required 50 missions to go home; whereas, the 8th AAF only needed 25 missions?