By Pat McTaggart

The first days of May 1945 found the German war machine in absolute chaos. Berlin had fallen, and entire German armies were surrendering en masse. Most of Europe was under Allied control, and in liberated capitals wild celebrations were already under way to mark the coming end of the war.

In the capital of Czechoslovakia, however, the mood was still somber. German units patrolled the streets, and the heel of the Gestapo still put fear into the hearts of city residents. Even the death of Hitler and the imminent fall of the Thousand Year Reich did little to deter the German troops in and around Prague from continuing to follow the day-to-day routine.

The situation in Czechoslovakia was in complete disarray during those first days of May, and the players in the final quest for the liberation of Prague only added to the tumult. In the western part of the country, American troops under General George S. Patton, Jr., were advancing, sweeping aside most German opposition. The Red Army, along with some new Eastern European allies, was moving in from the east.

German units, already decimated by the Red Army’s winter and spring offensives, were frantically trying to make their way westward to surrender to the Americans. In their attempt to reach the West, the Germans frequently fought pitched battles with a loose coalition of Czech Communist partisans and partisans loyal to the Czech government-in-exile, which was located in London. Another important player in the Prague drama was the Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia (KONR) Army, which was in an assembly area west of Prague.

Czechoslovakia was one of the first countries in Europe to fall under Hitler’s control. After Germany completed its Anschluss with Austria, Hitler turned his eyes to the Sudetenland, a part of western Czechoslovakia that had a large population of ethnic Germans. The Sudetenland, a rugged mountainous area, contained a vast system of defensive positions designed to protect Czechoslovakia from any enemy attacking from the west. It also contained a great deal of the country’s iron and steel works as well as major armaments factories.

Ethnic Germans, backed by Germany, began clamoring for a “Return to the Reich” in 1938, and street brawls between Czechs and the German minority resulted in casualties on both sides. At the same time, Berlin began a propaganda offensive designed to enflame the German public by reporting supposed Czech atrocities against their ethnic brothers.

The Czech government turned to the West for help. The result was the famous September 1938 meeting in Munich between Germany, France, Italy, and Great Britain at which there were no Czech representatives present. In exchange for Hitler’s promise to make no more territorial claims and a German guarantee to preserve the national integrity of the remaining portion of Czechoslovakia, the Sudetenland was ceded to Germany and was incorporated into the Reich in January 1939.

Hitler’s promise was broken two months later, and on March 15 German troops marched into Prague with hardly a whimper heard from the Western powers. The nation of Czechoslovakia was effectively dissolved later in the month. Czechoslovakia was divided into two parts: the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in the west and Slovakia in the east. Poland and Hungary were also able to annex small portions of the country.

Slovakia was governed by Roman Catholic priest Josef Tiso, a staunch supporter of Hitler. Under a treaty with Germany, Slovakia came under the Reich’s protection. Many Slovaks were already pro-Fascist, and the country would contribute a Schnelle Division (fast motorized division) and a security division, as well as two fighter squadrons and a reconnaissance squadron, to fight on the Russian Front when Germany invaded the Soviet Union.

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was permitted to be governed by a civilian administration under a Czech president, Dr. Emil Hácha, but in reality it was a German satellite with most of the power in the hands of the Reichsprotektor. In the early days of the German takeover, the day-to-day running of the Protectorate fell to the deputy Reichsprotektor, who also had economic responsibility for the production of the Czech factories and mines.

The economic facet of the Protectorate was of major interest to the Reich. The Czechs continued to work at their old jobs in the ore mines and the famous Skoda armaments and munitions plants, which were now totally geared to increasing the strength of the German war machine. Although rations were cut by the Germans, the workers were still grateful that they were being paid and that the Czech people were not subjected to the same harsh treatment that befell the Poles after the German conquest of that country in September 1939.

A Czechoslovak government-in-exile was formed in Great Britain under Eduard Benes, but that entity was half a continent away. There was a loosely organized resistance movement funded by the British, but it was largely ineffective during the first years of the war.

When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, members of the Czech Communist Party, who had up to now obeyed orders not to antagonize the Germans, began to form their own resistance groups. These groups would become more effective than the pro-democratic partisans, but it would take months of planning and organization before they would become more than a nuisance to the German occupiers.

A superb athlete with a brilliant organizational mind, Heydrich soon worked his way into the inner circle of the SS.

A turning point in the German-Czech relationship came in September 1941. On the 27th of that month, Adolf Hitler received the following message:

“Mein Führer,

I dutifully report that this afternoon, in accordance with today’s Führer Decree, I took over the leadership of the affairs of Reichsprotektor of Bohemia-Moravia. The official takeover follows tomorrow at eleven in the morning with the ceremonies at Hradcany Castle.

All political reports will reach you by the hand of Reichsleiter Bormann.

Heil mein Führer, and thank you for your confidence.

(signed) Heydrich. SS Obergruppenführer”

The author of that letter was Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich, “Heydrich the Hangman.” Following a checkered past in the Navy, Heydrich had joined the fledgling SS and soon attracted the eye of Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler. A superb athlete with a brilliant organizational mind, Heydrich soon worked his way into the inner circle of the SS.

Heydrich organized the SS Sicherheitsdienst (SD, the SS Security Police) before Hitler came to power. His collection of files on friend and foe alike made him one of the most feared and dangerous men in the Third Reich after the Nazi takeover in 1933. The SD became so powerful that it was often described as “the brains of the Party and the State.”

As Heydrich’s power grew, he became involved in the so-called Jewish problem. It was Heydrich who presided over the infamous Wannsee Conference on January 10, 1942, where the extermination process that cost the lives of 11 million people was decided.

When he took his new position in Prague, Heydrich immediately set about consolidating his power. His predecessor, the ineffectual and incompetent Konstantin von Neurath, had been sent on permanent sick leave, and the meticulous Heydrich had no reason to share duties with any deputies. Setting himself up in Hradcany Castle, Reichsprotektor Heydrich began to build his own fiefdom. There was no one to oppose him.

Heydrich earned his nickname, ”The Hangman of Europe,” by ruthlessly cracking down on any form of resistance to the German Reich. Intellectuals, writers, priests, and anyone else who could sway the population were rounded up and marked for “further treatment.” Death squads executed prisoners daily in the courtyard of Hradcany Castle, often with Heydrich watching from his office windows.

While the Reichsprotektor dealt with the resistance movement, he used a carrot-and-stick approach with Czech workers. Munitions plant laborers who made their quota were granted extra rations, and those that surpassed quotas obtained further privileges. As a result of these measures, Czech factories continued to furnish the German armed forces with high-quality and high-tech war materials as the Wehrmacht pushed deeper into the Soviet Union.

By the spring of 1942, the Czech exile government in London decided that something had to be done to revitalize the resistance movement, eliminate Heydrich, and discourage worker cooperation with the Germans. A team of assassins was dropped into the Protectorate, and on May 27, 1942, Heydrich was ambushed while being driven through the streets of Prague. He died in agony a week after the attack.

Heydrich’s assassination had its desired effect. The carrot was now gone from his equation, and Protectorate Higher SS and Police Leader Karl Hermann Frank now wielded the stick. With Heydrich gone, Frank became the real power in the Protectorate and would remain so until the end of the war.

Within hours of the ambush, Frank unleashed SS and security forces throughout the Protectorate. The men that shot Heydrich were finally cornered and killed in the basement of a Prague church, and hundreds, if not thousands, were rounded up for questioning or execution. One of the most infamous German reprisals was the total eradication of the village of Lidice. The entire village was razed, and the men and women were slaughtered or sent to concentration camps while the children who survived were either sent to camps or were adopted by German families.

The massive German response to Heydrich’s death assured the Allies that a growing resistance movement would soon flourish in the Protectorate, impeding war production and causing precious troops to be diverted for security duties. For the next three years, the Czech population would suffer under the heavy- handed policies of Frank and his cronies. By early 1945, the Czechs were more than ready to strike a death blow to their occupiers.

In early April 1945, Adolf Hitler was still in denial about the situation he faced. The Soviets were gathering more than 1.5 million men for their final assault on Berlin. Reserves were almost nonexistent, and commanders facing the Russian forces along the entire Eastern Front were either in retreat or holding on by the skin of their teeth against the enemy.

Generaloberst (colonel general) Gotthard Heinrici, the commander of forces in front of Berlin, was told that he would be receiving reinforcements that had escaped from East Prussia to bolster his line. He had also managed to put together a few understrength armored units that would be used as a reserve force to counter any Soviet breakthrough. The German general knew that his position was all but hopeless, but he hoped to gain time and at least slow the Russian juggernaut enough to allow civilians populating the east to flee westward.

Hitler, on the other hand, did not seem overly concerned about a Soviet attack on his capital. His eyes were on the Red Army advance through Slovakia, which was defended by the troops of Field Marshal Ferdinand Schörner’s Heeresgruppe Mitte (Army Group Center).

Schörner, a favorite of Hitler, was a fairly mediocre commander, but he was totally loyal to his Führer. Since January, Heeresgruppe Mitte had been slowly pushed back across Slovakia by the forces of General Ivan Y. Petrov’s 4th Ukrainian Front and General Rodion I. Malinovsky’s 2nd Ukrainian Front. Included in the Soviet Fronts were Czech, Romanian, and Polish units.

Both Hitler and Schörner were certain that the Soviet buildup in front of Berlin was a gigantic deception. “My Führer,” Schörner had said to Hitler, “remember Bismarck’s words, ‘Whoever holds Prague holds Europe.’” Hitler, who fancied himself as a modern-day cross between Bismarck and Frederick the Great, agreed with Schörner’s assessment. Prague must be held at all costs.

On April 5, four of Heinrici’s precious armored units were taken from his Heeresgruppe Weichsel (Army Group Vistula) and sent south to reinforce Schörner. Several of the promised units from East Prussia were also diverted to Heeresgruppe Mitte.

While Hitler Moved Forces Back and Forth on His Military Maps, with Little Regard to the Actual Difficulties Faced by His Commanders

Heinrici immediately rushed to Hitler’s headquarters to confront the dictator. Refusing to be silenced by Hitler’s aides, he angrily demanded the return of his units.

“I’m very sorry,” Hitler said, “but I had to take them from you. Your panzers are needed much more by your southern neighbor. The main attack of the Russians is clearly not aimed at Berlin. There is a stronger concentration of enemy forces to the south.”

Hitler continued to lecture Heinrici on the importance of stemming the Russian advance through Slovakia. He dismissed the Soviet buildup in front of Berlin and said that there would probably be a secondary attack against Heinrici’s forces in support of the main Soviet objective.

“The main thrust of the enemy will not be directed at Berlin—but here,” he said. Going to a field map, Hitler placed a finger directly on Prague. “Consequently, Heeresgruppe Weichsel should be able to withstand the secondary attacks.” With those words, Hitler had upped the ante for control of Prague. He had also sealed his own fate and the fate of the people of Berlin.

While Hitler moved forces back and forth on his military maps, with little regard to the actual difficulties faced by his commanders, most of the players in what was to become the Prague Uprising had now gathered in the Protectorate and in Slovakia. As was previously mentioned, the Red Army and some Allied units were battering Heeresgruppe Mitte from the east. Upon entering Slovakia, the Soviets established a “National Front” in Kosice, a city in the eastern part of the province. It was a loose coalition of Communist, Socialist, and exile government representatives, but was largely controlled by the Communists.

The Czech Resistance, emboldened by Soviet successes in the east since mid-1944, was now a force to be reckoned with. A revolt in Slovakia had been put down by the Germans with bloody fighting and massed reprisals in September. The uprising had received the blessings of the exile government, and it had made the group more cautious when it came to condoning the same thing in the Protectorate. Even in the spring of 1945, the memory of the failed Slovak adventure made the exiled officials extremely reluctant to call for another national uprising.

In April 1945, resistance hit-and-run attacks were the order of the day. Field Marshal Schörner’s Heeresgruppe Mitte, reeling from Soviet attacks in Slovakia, had already retreated into the Moravian province of the Protectorate. Attacks on German supply lines and depots hampered German defensive operations and sucked troops from the front to counter the partisans.

Resistance forces in Prague engaged in harassing attacks against the garrison, but the strong German presence made any large-scale attacks impractical. The Kommandant of Prague, General Rudolf Toussaint, had several ad hoc Army, security, and SS units, as well as the core garrison units, with which to battle any insurgents.

Toussaint, born in 1891, had been the Wehrmacht Plenipotentiary to the Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia since July 1944. In that capacity, he was privy to the roundup and transportation of Czech Jews and Gypsies to the death camps, and he worked closely with the SS in supplying antipartisan forces to counter the Czech Resistance. As Kommandant of Prague, Toussaint was determined to hold the city for as long as possible.

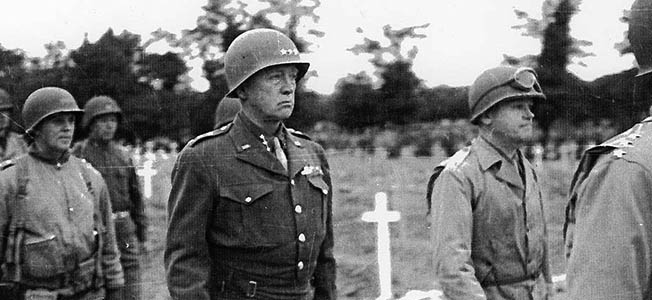

The Red Army and the Czech Resistance were not the only problems for Toussaint and Schörner. At the western border of the Protectorate, General Hans von Obstfelder’s 7th Army was facing the powerful Third Army of General George S. Patton. The Third Army was in a perfect position to slice through the weakly defended German line and enter the Protectorate, but Allied aims did not coincide with the situation.

The liberation of Czechoslovakia was given a low priority by the Western Allies. A demarcation line had already been agreed upon with the Soviets, and with the Red Army already controlling much of Eastern and Central Europe, it was the view of most Allied commanders that the Russians were in a much better position to liberate the country.

Patton was champing at the bit to unleash the Third Army, and he sent requests to his immediate superior, General Omar Bradley, to be allowed to take western Czechoslovakia. Those requests were denied by both Bradley and General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander, who had the unpleasant burden of making not only military decisions, but political ones as well.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, on the other hand, was in favor of wresting as much land away from the advancing Red Army as possible. His was a voice in the wilderness as he pushed for Allied forces to take Prague as soon as possible.

On April 21, the first Soviet artillery shells fell on Berlin. The final act was now closing on the German-Soviet war, but Hitler would not be around for the finale. Germany was on the verge of collapse, and the people in the still-occupied sections of the continent waited with increasing impatience for the end to finally come.

With the fall of Berlin, Prague was the only European capital that had not been liberated from the Germans. The German armed forces were still a fighting entity, but there was a vast difference in the outlook of troops engaged in the East compared to their comrades fighting in the West. For German soldiers on the Western Front, surrender, although distasteful to many, was a ticket to life after the war. Hitler was dead, Berlin had fallen, and the enemy occupied most of the Fatherland, making further resistance seem very futile.

Those German troops unlucky enough to be fighting the Soviets had a different set of goals. Even at this stage of the war, surrender was seen as a most unhealthy alternative. German soldiers taken by the Red Army were frequently beaten or shot out of hand, and being sent to a prison camp in the Far East or the Urals was just short of a death sentence.

The final hope for the men of Schörner’s Heeresgruppe Mitte was to make a fighting retreat to the West, where they could hopefully escape the Red Army and surrender to the Americans or the British. This was the goal that just about every one of Schörner’s soldiers was trying to achieve.

Bunyachenko was the Commander of Perhaps the Most Important Player in the Liberation of Prague, but He did not Know it at the Time.

Fighting was moving closer and closer to Prague, and both the general population and the resistance fighters were growing increasingly eager for freedom from German rule, but the multitude of parties and factions that made up the Resistance movement in Prague impeded any unified plans to take back the city. Members of the Communist underground movement, the Czech National Committee, the Czech National Council, and splinter groups such as the Military Group Alex all vied for dominance, pushing their own plans to oust the Germans.

While proposals and counterproposals for an uprising were being discussed, Heeresgruppe Mitte was being pressed into a pocket east of Prague. The Soviets, now done with the Berlin Offensive, sent Marshal of the Soviet Union Ivan Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front speeding south to be in on the kill. His units were moving rapidly through Silesia, and they were poised on the northern Czech border by May 4.

General Toussaint received reports of the growing unrest in the streets of Prague while, at the same time, keeping abreast of the deteriorating military situation. His garrison troops were enough to keep an unsettled population in line, but if a general uprising were to take place, they would be hard-pressed to hold the city. With Schörner’s men fighting for their lives there were hardly any units in Bohemia that were not engaged with the enemy or that could be used as a “fire brigade” to reinforce the Czech capital.

About 40 miles west of Prague, General Sergei K. Bunyachenko sat in his headquarters. Bunyachenko was the commander of perhaps the most important player in the liberation of Prague, but he did not know it at the time. Born in 1902, the Russian general had served as chief of staff of the Red Army’s 26th Rifle Division from 1940-1942. He was the commander of the 389th Rifle Division and the 59th Rifle Brigade later in 1942 and was captured by the Germans that same year. Bunyachenko—a former officer in Stalin’s Red Army—was now commander of the 1st Division of the KONR Army, which has often been confused with the Russian Liberation Army (ROA), an organization in which many of the KONR troops had previously served.

The driving force behind an anti-Soviet Russian army was General Andrei Andreivich Vlasov, a distinguished Red Army officer who was captured during an attempt to relieve Leningrad in 1942. Vlasov felt betrayed by Stalin, who had made no effort to relieve his encircled army. For the next two years, the embittered general worked with pro-Russian German officers and diplomats to try to build an anti-Communist army from the vast number of Russian prisoners held in German captivity.

The Wehrmacht was already using about a million Russian volunteers to help with supply and noncombat duties on the Eastern Front, a fact kept from top Nazi officials. The inane racial bias against the Slavs had a telling effect on the growth of the Soviet partisan movement while, at the same time, depriving the Germans of an enormous anti-Communist military force that could have been used against the Red Army.

Worsening conditions on the Eastern Front finally got Vlasov some grudging concessions from Party officials. On November 14, 1944, a conference was held in Hradcany Castle. High-ranking SS and Wehrmacht officers crowded the castle’s Spanish Hall to hear Vlasov set out his own manifesto concerning equality and democracy in a new Russia that would be liberated by his own anti-Soviet Russian army.

Surprisingly, Vlasov was given a green light to begin forming his army, which was to be part of the KONR. The news made its way through POW camps, and by the end of the month, former Red Army soldiers were signing up for the new formation in the thousands. Vlasov had finally gotten his wish, but it was too little too late.

The deteriorating situation on both the Eastern and Western Fronts had already taxed German war production to the limit. Only about 50,000 men, trained and equipped in two divisions, were chosen from the volunteers. These two divisions were designated to form the core of the KONR Army, but it was a futile undertaking.

After a somewhat disastrous attempt to stem the Soviet drive across the Oder, Vlasov ordered his divisions to move south to Bohemia. Knowing that the war was lost, he hoped that he could save his men by surrendering to the Americans. In the current climate, the Western Allies seemed to be the only chance the KONR Army had.

On May 4, Konev was poised to drive into the northern flank of Heeresgruppe Mitte. On the same day, the entire 11th Panzer Division surrendered to American forces, opening a wide gap in the lines of the 7th Army. The road to Prague was open, and Patton gleefully asked Bradley once again for permission to move into western Bohemia.

His wish was granted at 1930 hours on the 4th, and within the hour, the Third Army poured into the province. Patton’s forces advanced on a broad front, brushing aside most opposition as tanks and infantry rolled through the countryside. News of the American advance caused spontaneous uprisings in a number of cities along Patton’s route.

In Prague, the various resistance leaders heard the news and immediately called a special meeting that included all the major groups. They argued into the evening about if, or when, an uprising in the city would take place. The Czech National Council opposed any preemptive action, but other factions pointed out that there had already been an increase in clashes with the German garrison. The people of Prague, they argued, could not be put off any longer. The National Council finally relented. It was time for action.

During the early hours of May 5, emissaries from the Czech National Council arrived at General Bunyachenko’s headquarters. The Czechs told the Russian general that Prague would be in full revolt later in the day and they appealed to Bunyachenko, as a fellow Slav, to help liberate the city and fight the German garrison.

Bunyachenko was moved by the request, but he was still under Vlasov’s orders to remain where he was so he could hopefully surrender to the Americans. A call went out to Vlasov, and a heated exchange took place between the two Russian generals. It is not clear whether Vlasov acquiesced or Bunyachenko took matters into his own hands, but the KONR 1st Division was headed toward Prague within hours.

“Calling all Czechs. Come to our Help at Once. Come and Defend Czech Radio. The SS are Murdering Czech People Here. Come and Help Us.”

On the morning of May 5, resistance fighters gathered weapons and filtered out to predesignated positions. An important part of the uprising would be getting information to the general population. To accomplish that goal, it was vital for the rebels to take control of the powerful transmitters of Prague Radio.

General Toussaint, already anxious about reports of fighting in the city the previous day, sent orders for his troops to go to high alert. Some of the communications lines between his headquarters and subunits had already been cut; the other units received the message and began preparing for action.

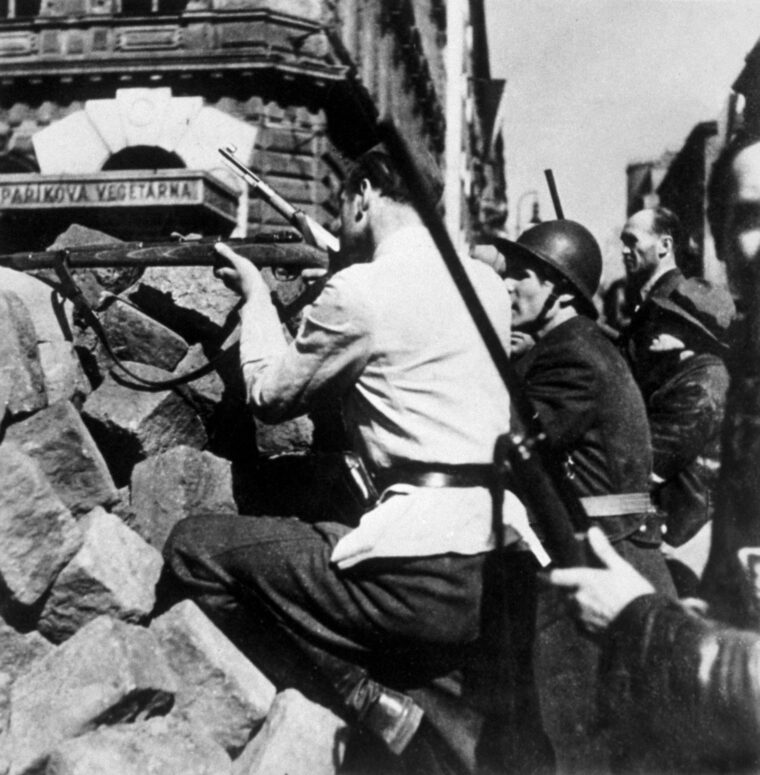

Meanwhile, resistance fighters were on their way to seize Prague Radio. Group Alex was at the forefront in the opening stages of the revolt against the Germans. Rushing the radio building, which was located on Vinohradská Street, the Czechs were able to take over the communications center. At 1233 hours, Prague Radio broadcast its first appeal to the public to rise against the German occupiers. Even as the broadcast was going out, members of the resistance and the Czech police were battling the SS troops charged with guarding the station.

With the sound of combat as a backdrop, the announcer asked for public support with the following message: “Calling all Czechs. Come to our help at once. Come and defend Czech Radio. The SS are murdering Czech people here. Come and help us. You can still get through the Bilbinava Street entrance …”

To manage the military aspect of the uprising, Group Alex’s General Karel Kutlvar was named commander of Prague. His small staff was charged with coordinating the activities of the resistance groups. Other public buildings were seized in the first chaotic hours of the uprising, and Czechs and Germans fought running battles in the streets as armed groups blundered into each other.

During the afternoon of the 5th, the Czech National Council took over political control of the revolt, putting General Kutlvar and his staff under Council authority. At about the same time, newly appointed mayor of Prague, Václav Vacek, pledged his allegiance to the Council, putting the city government squarely on the side of the rebellion.

Antonin Sum, a teenager at the time, was involved in the resistance. “The uprising started in Prague,” he said. “You could see in the streets, as I saw myself, people with guns, which was absolutely impossible before. They were guns that had been hidden away somewhere underground in caves.… It was just the start, but nobody knew what was practically going on.”

Prague Radio continued its broadcasts to the people. At about 0100 hours on May 6, the radio called on residents to build barricades throughout the city and to defy the Germans at every turn. Thousands took to the streets in reply to the appeal. In scenes reminiscent of European uprisings in the 19th century, cobblestones were torn from the streets to form the foundations of barricades. Carts, vehicles, and trolleys were overturned to block key intersections, and snipers took to the rooftops overlooking choke points. By morning, more than 1,600 barricades had been erected.

Broadcasts from the radio station now reached out beyond Prague in hope of a quick rescue from the Allies. “Here is Prague!” one broadcast said. “Here is Prague! Americans and English—help us! We need guns. There are too many Germans!”

The Americans heard. The English heard and the Russians heard—yet no one did anything. Patton had reached the city of Plzen (Pilsen), about 50 miles west of Prague. That was the deepest penetration that Eisenhower would allow. The rest of Czechoslovakia had been promised to the Soviets, and that was that! The Red Army, still fighting Schörner’s Heeresgruppe Mitte, also chose not to send help. The more Czech Resistance fighters killed by the Germans, the easier it would be to install a Communist government after the fighting ended.

In Prague, May 6 was a day of crisis. General Toussaint, taken aback by the previous day’s action, was now marshalling his forces to crush the rebellion. About half the city was occupied by the resistance, and his scattered units needed time to concentrate. Barricades and snipers made treks to assembly points hazardous affairs, but the Germans were able to gather units close to the radio station.

Toussaint also radioed Schörner for help. Although Heeresgruppe Mitte already had its hands full, an enraged Schörner sent SS units toward the city to help put down the uprising. One of those units was Kampfgruppe (Combat Group) Wallenstein, composed of two understrength infantry regiments, an assault gun battalion, and other affiliated detachments.

Reinforced with the SS units, the Germans struck at the radio station. As resistance fighters tried to stem the tide of infantry, assault guns, and tanks, a new voice came over the airwaves begging for help from the Allies. “Prague is in great danger! The Germans are attacking with tanks and planes. We are calling urgently our allies to help. Send tanks and aircraft immediately. Help us defend Prague. At present, we are broadcasting from the radio station. Outside, there is a battle raging.”

The voice belonged to William Grieg, a Scottish POW who had escaped from the Germans. Grieg found himself in the middle of the uprising and was asked by the Czechs to make the appeal. With fighting erupting all around him, Grieg calmly sat in front of the microphone and sent out the urgent request.

The Czechs fought bravely, but the Germans were too strong. They recaptured the radio station, but Czech engineers had already removed enough equipment to set up another broadcasting center in a safer part of the city. Grieg was called back into action later during the uprising to ask for an Allied air strike against a German armored column that was advancing on the city. Unlike his first appeal, that request was answered and the German column was decimated. Hearing of Grieg’s first call for help, Patton once again phoned Bradley and Eisenhower to ask permission to move on the Czech capital. “I’ll call you tomorrow from Prague,” he told Eisenhower. Once again, in no uncertain terms, the feisty general was told to hold his position and under no circumstances was he to advance any farther.

“I am now a General Without an Army”

Patton did, however, send a three-man team racing toward Prague in a jeep. Making their way into the embattled city, the trio observed the plight of the resistance fighters and then returned hastily to Patton’s headquarters. When the general received their report, he made a final call to Bradley pleading for freedom of movement. The request was forwarded to Eisenhower, and once again the request was denied.

While the Americans stood idle, General Bunyachenko was pushing his troops to reach Prague. The first few units of his division entered the city on the 5th, but the bulk of the 1st KONR Division arrived on the 6th. Bunyachenko immediately threw his forces into the fray.

The Russians were soon side by side with the Czechs fighting the Germans, who had been so confident earlier in the day. It was a surreal scene with men on both sides wearing the Iron Cross and many other identical combat decorations trying to kill each other. Fighting lasted into the night, with the Russians gradually pushing the Army and SS forces back.

General Toussaint reported the situation to Schörner, who was outraged at the betrayal of the KONR. He promised more SS units to Toussaint, who by now was contemplating a cease- fire or surrender. The German Kommandant hoped to save what was left of his command from the Red Army, which was now pushing toward Prague despite the fanatical resistance of Heeresgruppe Mitte.

Upon hearing reports of more German troops on their way to join the battle, Bun-yachenko ordered his reserve regiment to take up blocking positions on a hill about eight miles from the city. When an SS unit finally appeared, it was met with a withering fire from the Russians, who had dug in on the hillside. The SS were stopped in their tracks, and assault after assault was repulsed by Bunyachenko’s men.

With the SS relief force stalled and the KONR and resistance fighters closing in from all sides, Toussaint formally requested a truce. Blindfolded, he was led to the National Council headquarters. For more than four hours, Toussaint alternatively argued and pleaded. He offered to surrender the city but asked that the garrison be allowed to march west and surrender to the Americans.

News of the impending surrender of all German forces in Europe had already reached Prague, and the Council saw no reason now to continue fighting—it would just cost more Czech lives. Toussaint’s terms were finally accepted, and word of the liberation soon spread throughout the city. “I am now a general without an army,” Toussaint exclaimed as he left the meeting.

German forces hurriedly gathered to form convoys for the drive to the west. As garrison forces left the city, Prague celebrated its liberation. There were also acts of revenge and atrocities committed against German and ethnic German civilians that remained in the city. May 8 was a day of liberation, but it was also a day of retribution for six long years of suffering caused by the Germans.

Bunyachenko’s men were also leaving. Konev’s divisions were finally near the outskirts of the city, and every KONR soldier knew what awaited them if they fell into the hands of the Red Army. Joining the KONR 2nd Division, the Russians, about 50,000 strong, marched southwest toward an uncertain fate.

About half of the KONR Army managed to make it through encircling Russian units to the American lines. In small groups they infiltrated through Soviet advance elements to surrender to the United States Army. Some of those who had surrendered to the Americans were returned to the Soviets, but most managed to remain in the West. The unlucky half that did not make it was doomed, for the most part, to a long slow death in the Gulags. Vlasov, Bunyachenko, and some 20 other KONR and ROA generals were given a show trial in Moscow and then executed.

General Toussaint was turned over to the Czech government for trial. He was sentenced to life in prison for his part in the transportation of Jews and Gypsies to the camps and for crimes against the Czech people, but was released in 1961. Some say that he was released because of services rendered to Soviet intelligence while in prison. Toussaint died in 1968.

Patton’s forces never did reach Prague. On May 9, Konev’s forces finally entered the city with great fanfare. The date was officially named Liberation Day, although it was the Czech people, with KONR backing, who liberated the city the day before. Between 1,700 and 2,000 Czechs were killed in the uprising, and thousands more were wounded.

The exile government returned to Prague on May 10 and promptly dissolved the National Council. Resistance leaders were delegated to minor positions and were not represented in the new national government. Soviet forces now occupied almost all of the country, and within months, under the Potsdam Agreement, hundreds of thousands of ethnic Germans were expelled from the Sudetenland.

Under Soviet occupation, the fledgling democratic government went the way of Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, and other countries in the Russian sphere of influence. In 1947, the Slovak Democratic Party was made virtually impotent. By February 1949, all Czech democratic parties were eliminated, and a few months later the Communists officially took over control of the government.

History books were rewritten, and the Prague uprising was given a minor place in the liberation of the capital. Soviet forces were given the lion’s share of credit for liberating Prague and, of course, there was no mention of Bunyachenko or the KONR. It was some years after the fall of Communism that the entire true story came out.

Prague was not, as most history books claimed, freed by the Red Army. The true heroes were members of the Czech Resistance, the Czech people, and a forgotten army of turncoat Russians that had fought its final battle against the very forces that had once been its greatest hope.

Pat McTaggart is an expert on World War II on the Eastern Front. He writes from his home in Elkader, Iowa.

Pat….

What would be the best book on the Prague uprising or the entire campaign in Czechoslovakia as a whole?

Thanks

Al Cagle