By Sam McGowan

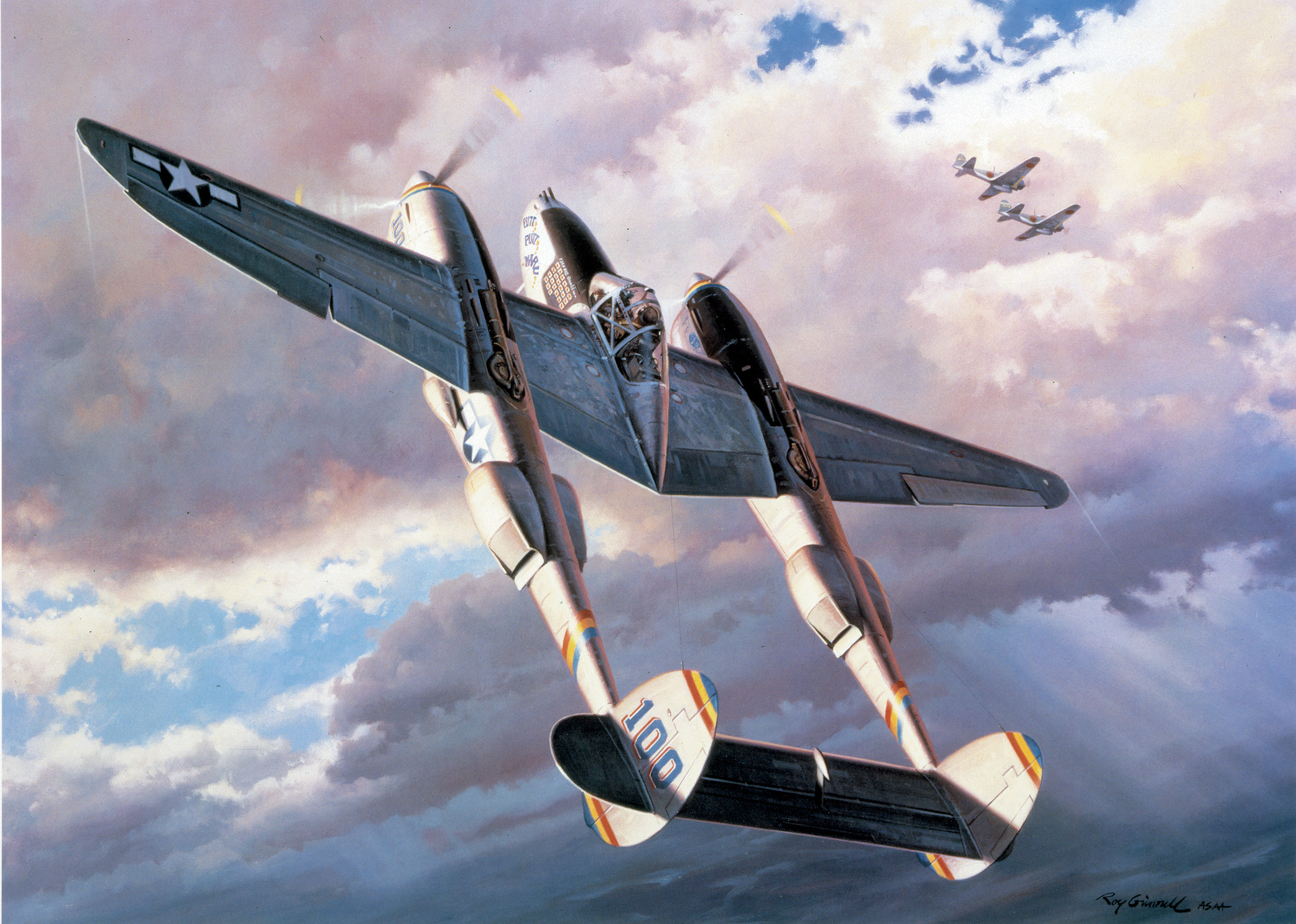

Due largely to their use in the postwar U.S. Army Air Forces and present proliferation among the air show community, the North American P-51 Mustang is thought of by many as the most important American fighter of World War II. In reality, however, the P-51 was a relative latecomer to the war, and even though it achieved a remarkable record during the last year of the war in Europe, it was not the fighter that first allowed Allied forces to gain air superiority over the Axis. By the time the redesigned Mustang made its appearance in the skies in Europe in the late winter of 1944, the Allied air forces were already clearing the skies in both Europe and the Pacific of German and Japanese aircraft and were in the process of gaining complete air superiority. This was all due to the twin-boomed, twin-engine Lockheed P-38 Lightning and the single-engine Republic P-47 Thunderbolt. And in the Pacific Theater, the P-38 was the preferred fighter right up to the end of the war, even above the soon-to-be-famous Mustang.

Lockheed began developing the P-38 Lightning in 1937 as the company’s first venture into the military airplane market at a time when the U.S. military was modernizing its air forces in response to developments in Europe. Although the Army was somewhat skeptical of Lockheed’s promise of a 400 mph-plus airplane, the twin-engine fighter design was approved in mid-1937, and in January 1939 the prototype made its maiden flight. President Franklin D. Roosevelt had just ordered an increase in the production of new fighter designs, and the Army gave Lockheed an order for 13 test airplanes in April 1939. A followup order for 69 production aircraft was awarded by the Army in September. In spite of the company’s failure to deliver the first of the test airplanes, Lockheed was given a huge order for 607 P-38s in August 1940, as events in Europe indicated possible future U.S. involvement in the war that had increased in fury only a few weeks before. Production problems caused deliveries to lag. By December 7, 1941, only 69 Lockheed P-38s were in service with the U.S. Army Air Corps.

Because of the airplane’s value as a high-altitude interceptor, P-38s were held in the United States for homeland defense during the early months of American involvement in the war, except for a handful that were sent north to Alaska in the late spring of 1942. Consequently, it was in the Aleutians that the famous Lightning made its combat debut. Eleventh Air Force P-38s were assigned primarily as escorts for long-range Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers, but also served in ground attack and reconnaissance roles.

The First Lockheed P-38 Lightning Fighter Groups to Deploy Overseas

Plans were made to deploy several squadrons of P-38s to England, but the logistics of delivery were difficult. The 1st, 14th, and 82nd fighter groups were the first P-38 groups to go overseas, joining the Eighth Air Force in England. The 1st remained in Iceland for a time, then continued on to England where the three groups flew a few missions over France without engaging the Luftwaffe.

In the fall of 1942, all three groups were ordered to deploy to North Africa to join the newly organized Twelfth Air Force, which had been created to support American forces assigned to Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa. A fourth group, the 78th Fighter Group, was held in “strategic” reserve in England. When the three groups deployed to Africa, none of them had engaged in air-to-air combat and there were no indications of how the P-38 was going to perform in that role.

The P-38 Lightning groups were plagued with problems—two were lost to enemy air attack on November 20, and on the night of November 21, six airplanes were lost when they tried to land at an advance base after dark. Three days later the P-38s had their first successes, as they shot down several German and Italian transports near Gabes in Tunisia. The P-38s were used in a variety of roles in North Africa. In addition to their normal fighter duties of intercepting enemy formations and escorting friendly bombers, they were also used in a ground attack role, strafing enemy vehicles and troop concentrations. Their longer range and endurance made the P-38s the only fighters in the theater capable of the longest missions.

By early 1943, the P-38 groups in North Africa were desperately short of airplanes, forcing Twelfth Air Force commander General James H. Doolittle to scour the United Kingdom for more Lightnings. When Army Air Forces commander General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold came to Casablanca for a high-level conference, he recognized the seriousness of the situation. He ordered that all remaining P-38s in England be sent to North Africa and that additional P-38s should be sent directly to North Africa by ship from the United States. His order also brought the 78th Fighter Group’s planes and pilots down from England to reinforce the three Twelfth Air Force groups; other group personnel remained in England to re-equip with P-47s.

Due to British naval control of the Mediterranean, the German Army in North Africa depended heavily on air resupply and reinforcement. In the early spring of 1943, the Allied air forces elected to make the German transports a major target. P-38 Lightning sweeps over the Mediterranean became the order of the day.

“Palm Sunday Massacre”

On the morning of April 5, a group of 26 Lockheed P-38s intercepted a German formation of 50 to 70 Junkers Ju-52 transports escorted by about 30 other aircraft, including Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters and Junkers Ju-87 dive-bombers. The action resulted in claims of 11 of the transports and four other German aircraft shot down for a loss of two P-38s.

Another P-38 formation escorting North American B-25 Mitchell medium bombers on a low-altitude attack on shipping claimed 15 German fighters. Over the next week the P-38s claimed scores of German transports and dozens of fighters. The successes of the P-38s set the stage for the “Palm Sunday Massacre,” when Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk and Supermarine Spitfire fighters intercepted a large formation of German transports and claimed one hundred, effectively cutting the German supply lines to the Afrika Korps, which was battling for its life in North Africa.

The diversion of the P-38s to North Africa left American fighter forces in England at a very low level—in fact, the P-47-equipped 4th Fighter Group was the only U.S. fighter unit in England in the spring of 1943. Plans for Torch called for the original P-38 groups to be replaced by P-47 groups in England, but the heavy single-engine P-47 lacked the range for long-range escort. New fighter groups were organized in the United States and equipped with P-38s, then moved to England for escort duty with the Eighth Fighter Command. Their longer range made the P-38s the only fighters capable of staying with the bombers on the deep-penetration raids into Germany, and P-38s were the first Allied fighters over Berlin.

The versatility of the P-38 made it a suitable airplane for many missions, one of which was a daring low-level attack that was a repeat of the Operation Tidal Wave mission against the oil fields and refineries of Ploesti, Romania, made by B-24s on August 1, 1943. On June 10, 1944, a formation of 36 P-38s carrying 1,000-pound bombs was sent to Ploesti, escorted by 39 other P-38s not carrying bombs. Twenty-three Lightnings were lost on this disastrous mission, many to the deadly flak that made Ploesti second only to Berlin as the most heavily defended target in Europe.

The P-38 was also badly needed in the Pacific War, but the low priority of the theater kept the twin-engine fighter out of the region until late in 1942. The first American fighter squadrons in the Pacific were equipped with the Bell P-39 Airacobra and the P-40, both of which were decidedly inferior to the best Japanese fighters.

When General George C. Kenney received his orders to report to Australia to assume command of air units in the Southwest Pacific Area of Operations, he asked General Henry H. Arnold for P-38s to replace the older designs. Kenney also asked for a particularly aggressive young lieutenant named Richard Ira Bong who he had called on the carpet for unauthorized low-altitude aerobatics in a P-38, including looping the loop around the Golden Gate Bridge. Bong would later become the U.S. ace of aces with 40 confirmed kills in a P-38.

When the first P-38s arrived in Australia, they were discovered to have some design problems, and their combat debut was delayed. But by late 1942, P-38s had replaced some of the P-39s in the 35th Fighter Group and were soon to make their presence known to the Japanese in the skies over New Guinea. The 49th Fighter Group was still equipped with P-40s but would soon transition to the Lightning as well.

Victory by Accident: Lockheed P-38s in the Pacific Theater

The first P-38 victory in the Pacific came about as more of an accident than a deliberate attack. For several weeks the P-38 pilots had little success at encountering Japanese aircraft; the Japanese pilots seemed to be avoiding the twin-boomed fighters. In late November, a flight of P-38s was patrolling over the Lae Airdrome and issuing taunts to the Japanese over the radio when one of the Japanese fighter pilots decided to take off. A young P-38 pilot from New Orleans named Ferrault went down to attack the Japanese fighter, then remembered he was carrying bombs and quickly jettisoned them. His plan was to come around and attack the Japanese fighter as soon as its wheels were retracted. The bombs fell in the water off the end of the runway. The unfortunate Japanese pilot flew into the water that had been tossed skyward by the explosions and crashed into the bay. General Kenney kidded the young Cajun that he did not deserve the promised Air Medal that was to go to the first P-38 pilot to achieve a victory since he had not shot the Japanese plane down, but later that evening he went over to the squadron and gave him the medal.

December 27, 1942, was the day the P-38 began to take over the skies of the Southwest Pacific. A flight of 12 Lightnings was sitting strip alert at Laloki Aerodrome at Port Moresby when they got word that a large Japanese formation was headed their way. Captain Thomas J. Lynch, who had already achieved some success in P-39s, led the P-38s off the ground and climbed to intercept the formation of 25 Japanese fighters and dive-bombers.

When the battle ended, 15 of the Japanese formation had been claimed (the official history of the Army Air Forces in WWII lists nine Japanese fighters and two dive-bombers destroyed). Lynch himself claimed two, as did Bong. Lieutenant Kenneth Sparks also claimed a pair of Japanese fighters.

Reportedly, Bong’s two victories came about as a result of his aggressiveness. Although he had innocent good looks—Kenney referred to him as a “cherub”—Bong was very aggressive on the inside. He was not a particularly good shot, but he was an exceptional pilot and he achieved most of his earlier victories by pulling in as close as possible to his quarry and “putting the guns right in the cockpit.”

In his first action Bong reportedly was separated from the rest of the formation and found himself surrounded by several Japanese planes. He promptly shot two down and escaped unscathed. Bong achieved all 40 of his aerial victories in P-38s, but died at the end of the war while testing a new jet fighter.

The twin engines and longer range of the P-38s made them the ideal fighter for the South Pacific Area of Operations, and General Millard Harmon constantly pressed General Arnold for P-38s for his theater. In the late fall and winter of 1942, Allied forces struggled to wrest control of Guadalcanal from the Japanese. Henderson Field had been the major objective of the Marines who initially landed on the island, and a major struggle took place for control of it.

Japanese aircraft staged constant raids on American-held Henderson Field, which was defended by obsolete Marine Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters and U.S. Army P-39s and P-400s; the P-400 was an export version of the P-39 Airacobra. Both the F4Fs and the P-39/P-400s were lacking in performance and were unable to meet the Japanese fighters on their own terms.

In November 1942, General Douglas MacArthur ordered the temporary assignment of some P-38s to Guadalcanal due to the uncertain nature of the situation. A flight of eight P-38s from the 39th Fighter Squadron left Milne Bay on New Guinea on November 13 and flew directly to Henderson Field, where they remained for a week. A major air and naval action against the Japanese Navy began on November 14 and prevented the Japanese from resupplying their troops on Guadalcanal, thus deciding the final outcome of the campaign, though the island would not be clear of Japanese until February.

Which Lockheed P-38 Pilot “Got” Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto?

In early 1943, Headquarters, Army Air Forces finally began releasing a few P-38s for assignment to the Pacific to replace the performance-limited P-39s and P-40s. Once Guadalcanal was secure, the South Pacific Area of Operations began making plans to move northward through the Solomon Islands. In March the 18th Fighter Group moved to the South Pacific from Hawaii and joined the 347th Fighter Group, which was in the process of converting from P-40s to Lightnings. Shortly after their arrival at Henderson Field, pilots from the 18th joined with others from the veteran 347th for one of the most famous missions of World War II.

In early April, Allied code-breakers learned that Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Japan’s leading naval strategist and the architect of the air attacks on Pearl Harbor and Midway, would be flying on an inspection visit of Japanese installations in the South Pacific. American cryptoanalysts had determined Yamamoto’s exact itinerary, including the information that he was due to arrive at the airfield at Ballale on the island of Bougainville at 0945 on April 18.

No doubt still chafing over the humiliation of the Japanese victory over the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor nearly a year and a half before, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest J. King ordered Admiral William Halsey, commander of U.S. forces in and around Guadalcanal, to “Get Yamamoto.” Halsey relayed the order to the new Commander for Air, Solomons, a naval officer, Admiral Marc Mitscher.

Since the only Allied fighters in the theater capable of making the interception were P-38s, the order went to the Army. Eight pilots were chosen from the 18th Fighter Group’s 12th Fighter Squadron, two were chosen from the 70th Fighter Squadron, and eight more came from the 347th Group’s 339th Fighter Squadron. Captain Thomas Lanphier of the 70th Fighter Squadron was chosen to lead the four P-38s of the attack section. Major John Mitchell was in command of the operation and led the other 14 P-38s in the cover role.

The 18-airplane formation took off from Henderson Field on Guadalcanal at 0725 hours on the morning of the 18th and flew at wave-top height for more than two hours. As they neared the coast of Bougainville, the formation of P-38s sighted Admiral Yamamoto’s entourage. The two Mitsubishi G4M Betty bombers carrying the admiral and his staff tried to escape while six Zeros attempted to intercept the attack force. Captain Lanphier shot down one Zero then attacked one of the Bettys and sent it into the jungle in flames. Lieutenant Rex Barber shot down the other Betty.

Lanphier was credited with shooting down Yamamoto, but a controversy erupted between him and Barber over who “got Yamamoto” that continued for more than half a century. Regardless of who shot down whom, the flight of P-38s shot down Yamamoto and killed him and most of his staff. The Navy Cross was awarded to flight leader Major Mitchell and to each of the four pilots in the attack section.

In May 1943, the 475th Fighter Group was activated in Australia and planned to become the first group in the Southwest Pacific to be equipped solely with P-38s. At this time other groups were operating mixed bags of aircraft, including P-39s, P-40s, and P-47s as well as P-38s. Pilots and other personnel were drawn from other groups already fighting in New Guinea and sent back to Australia to form a nucleus around which the group would be built. Additional personnel arrived from the States to fill out the squadron while new airplanes were delivered by boat. By July 118 P-38s had arrived in Australia and were going through the modification program at Eagle Farms to bring them up to combat standards. By mid-August, the group was ready for combat and moved back up north to Dobodura, to join the 49th Fighter Group, which was operating P-38s and P-40s.

Range was one of the major problems facing the fighter commanders of the Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces. Unlike the war in Europe, which was waged over a comparatively confined area and mostly over land, the war in the Pacific Theater was fought over great distances that required long flights over water. The twin engines of the P-38 made it the ideal candidate for over-water flying. With a single-engine fighter, an engine failure meant that the airplane was coming out of the sky. A twin-engine fighter or light/medium bomber could lose one engine and still continue back to base.

Charles Lindbergh’s History with the P-38

General Kenney and his fighter commanders pondered the problems of their theater and constantly thought of new ways to extend the range of the combat squadrons. Extended-range fuel tanks afforded increased range, but in the summer of 1944 a godsend came to the theater, a man who would significantly increase the range and combat radius of the P-38.

In the spring of 1927, Charles A. Lindbergh singlehandedly extended the barriers of aviation when he flew the Spirit of St. Louis, a single-engine Ryan monoplane that he had helped design, across the Atlantic from New York to Paris. After the epic flight, Lindbergh, who was a trained fighter pilot and a member of the U.S. Army Reserve, continued making very long-range flights, sometimes accompanied by his wife, Anne.

Although he held a colonel’s rank in the Army Reserve, Lindbergh had resigned his commission in order to take a leadership role in the American isolationist movement. Having lived for several years in Europe, during which he visited with the air forces and flew the top fighters of many European nations, Lindbergh was strongly opposed to American involvement in the war. Lindbergh’s isolationism irked many prominent members of the Roosevelt administration, and when he applied to return to active duty after the Pearl Harbor attacks, his application was turned down by President Franklin Roosevelt, who commented to his staff, “I have clipped the wings of the Lone Eagle.

Even though he was not allowed to return to the military, Lindbergh nevertheless contributed greatly to the American war effort, first as a consultant with Ford Motor Company helping to work out the bugs of their contract production of Consolidated Liberator bombers and transports, then with United Aircraft, particularly in the F4U Corsair program. Lindbergh went to the South Pacific as a civilian technical representative for United Aircraft, assigned to the Marine F4U Corsair program, but he had not been in the region long before he became associated with the P-38.

Lindbergh was in the Pacific on U.S. Navy orders, but one of his personal missions was to make a comparison of the single- and twin-engine fighters in combat, so he obtained orders allowing him to go to New Guinea. When he got there, he went to General Whitehead and gave him a copy of his orders; he was told to join the 475th Fighter Group. Somehow, word of his arrival failed to reach General Kenney’s headquarters until after he had flown several missions.

When he learned that Lindbergh was in his theater—and flying combat missions in P-38s—Kenney invited the famous aviator down to Brisbane. When Lindbergh arrived in Australia, Kenney took him in to see General Douglas MacArthur, telling his boss that he had “an important job” for Lindbergh. MacArthur authorized Lindbergh to work for Kenney, who promptly sent the Lone Eagle back to New Guinea to teach the young fighter pilots how to get more range out of their airplanes.

Lindbergh’s solution to the problem was fairly simple. The Army pilots—and Marine pilots flying F4Us who also profited from his instruction—had been taught to fly their airplanes at high propeller rpm and high manifold pressure, which allows maximum power from a turbo-charged engine. Lindbergh told them to continue to fly at high manifold pressure, but to reduce propeller rpm, a technique that significantly reduces fuel consumption while allowing high power from the engines. The Army pilots thought such a technique would “burn up” their engines, but Lindbergh convinced them that this was not so. Kenney had authorized Lindbergh to fly combat missions on the condition that he not participate in the fighter escort missions against the most heavily defended Japanese targets. Soon Lindbergh was flying and teaching Army pilots to fly missions that previously had been far beyond the published range of the P-38.

Lindbergh’s time with the P-38s in the Southwest Pacific came to an end after he did, in fact, become involved in a fight with Japanese fighters and was credited with shooting down a Sophie, a Japanese float-plane fighter. A second aerial combat a few days later found Lindbergh with a Zeke on his tail and several others getting ready to gang up on him. Fortunately, Lindbergh was in the company of a trio of experienced fighter pilots, and they quickly broke up the fight and saved Lindbergh’s bacon.

When news of the aerial combat reached Kenney, he ordered Lindbergh grounded. Lindbergh went back to fly with the Marines on a few more missions, then returned to the United States with approximately 50 combat missions under his belt and one Japanese airplane to his credit. But he had left the fighter commanders in the Pacific with a priceless gift—the ability to greatly increase the range of their airplanes. On July 27, while Lindbergh was still flying with the 8th and 475th Fighter Groups, a P-38 formation had flown an unprecedented 1,280-mile mission escorting B-24s attacking Japanese positions in the Halmehera Islands northwest of New Guinea. Without Lindbergh’s instructions, such a mission would have been impossible.

It was among the P-38 pilots of the Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces that the number of aces was growing. Their longer range, especially after their effective combat radius was increased thanks to Lindbergh, allowed the P-38s to venture well into Japanese territory where the likelihood of encountering enemy aircraft was greatest. The P-38 groups were blessed with some highly skilled and aggressive fighter pilots, including Tommy Lynch, Tom McGuire, and Dick Bong. Lynch was the most experienced of the lot, having started his combat career against the Japanese in the under-performing Bell P-39 Airacobra. He and Bong became close friends shortly after Bong arrived in the theater in 1942, and the two teamed up.

Lynch, Kearby, and Bong: Who Shot Down More Enemy Fighters?

Another top-scoring fighter pilot in the theater was Colonel Neel Kearby, a P-47 pilot and commander of the 348th Fighter Group. Until March 1944, Lynch, Kearby, and Bong were in a neck-and-neck race for the top ace slot. Kearby and Lynch died within days of each other, Kearby on March 4 and Lynch on the 8th. Kearby was shot down by a Japanese fighter, while Lynch was hit by ground fire during a strafing run. Bong, alone, remained of the three top scorers. Kenney allowed him to continue to fly combat until April 10 when he broke World War I ace Captain Eddie Rickenbacker’s score of 26 enemy aircraft. A second enemy aircraft shot down the same day brought Bong’s official score to 27. Kenney promoted the young pilot to major and promptly sent him back to the United States to attend a gunnery school.

In mid-October, Major Dick Bong returned to the Far East Air Forces. During his absence, Major Thomas McGuire had been racking up a pretty good score and was within eight kills of tying Bong.

Bong told Kenney he had learned a lot in the gunnery school and wanted to put the knowledge to use. Ironically, Bong was not a very good shot and had never attended gunnery training prior to coming to the Southwest Pacific. Now that he had learned the tactics of aerial gunnery, he wanted to put it to the test. Kenney denied his request to return to a squadron but put him on his staff and assigned Bong to go around to the various squadrons and teach them what he had learned in the States.

Bong was allowed to fly missions and continued shooting down Japanese planes until he reached 40, at which point Kenney decided that he was too valuable to lose and sent him back to the States permanently. By this time, McGuire was within two kills of Bong’s score. On January 7, 1945, McGuire was killed when he stalled and spun into the ground while trying to get in position to help a fellow pilot who was under attack by an especially aggressive Japanese fighter pilot.

What Made the P-38 an Ideal Reconnaissance Aircraft

Because of its long range and twin engines, the P-38 was the favored airplane in the Far East Air Forces. When General Arnold notified Kenney that P-38 production was scheduled to cease in favor of P-51s, Kenney sent word back that he did not want or need any more P-51s, but that he wanted more P-38s. Kenney told former General Motors president General William Knudsen that the reasons he had given for wanting P-38s in September 1943 still held. Knudsen promised Kenney that P-38 production would continue. By war’s end, more than 10,000 Japanese aircraft had fallen to the guns of P-38s.

While the fighter version of the Lightning was taking on the Japanese and German Air Forces, the photo reconnaissance version of the airplane was also playing an important role. Early in the war, Army maintenance depots began converting P-38s into F-4 photo reconnaissance aircraft by removing the guns from the nose and replacing them with cameras. A production model of the Lightning reconnaissance aircraft was designated as the F-5.

Photo reconnaissance Lightnings played important roles in both Europe and the Pacific. In fact, the first P-38s to fly combat missions in the Pacific Theater were converted reconnaissance planes that were sent to Australia early in 1942. In early 1944, the modified P-51 Mustang was introduced to the European theater. The inclusion of additional fuel tanks in the wings and fuselage greatly extended the airplane’s range, and the P-51 soon became the favored fighter in Europe. Not so, however, in the Pacific, where the P-38 continued its reign right up to V-J day.

My dad with a lead man on the production line of P 38 At Lockheed in Burbank California. RIP E.J.Hellman ?????

I went Oshkosh to the Air show and some person had a beautiful Lightning with a polished skin. The person came several years than suddenly stopped. missed that plane and about 5 years latter I stopped to. Don Weber.

At least one of the P-38’s based in Iceland(after the US Amy [and Navy], took over from the US Marines, who, in turn, had taken over from the RAF and the British Army) shot down a German FW-200 in 1942.

Richard Bong, then working for Lockheed, was killed while flight testing the new XP-80 Shooting Star…

Famous author, Antoine Ste Exupery, flying for the Free French,was lost in a F-5 photo recon flight over Southern France.