By Dr. Carl Henry Marcoux

Ernest Taylor Pyle was born August 3, 1900, in Dana, Indiana. He came from a farm family. His father hired out as a laborer or worked as a sharecropper on farms around Dana. At the time of Ernie’s birth, the family home had neither indoor plumbing nor electricity, conditions that were not uncommon for households in rural Indiana at the time.

Although slight of stature, the young boy did a man’s work in the fields, helping his father when not attending school. During Ernie’s third year in high school, the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917. He wanted to join up immediately, but his parents insisted that he finish school first. After he received his diploma, Ernie left for Peoria, Ill., where he enrolled in the Naval Reserve. Before the Navy called him up, Germany signed the Armistice agreement.

Anxious to avoid a life of farming, Ernie enrolled at Indiana University, a college in the throes of expansion after the war’s end. There he met his lifelong friend, Paige Cavanaugh, who, during the war, had served in the Army overseas. Pyle became fascinated with the tales of Army life told to him by Cavanaugh and another old friend from Dana, Walter Lang. The experiences of these two friends undoubtedly affected his subsequent interest in reporting on the military.

The young student decided to enroll in the university’s journalism program. He went to work on the college newspaper and also helped produce the university yearbook. Soon Ernie became socially active on campus, joined a fraternity, and ended up as editor of the school paper. He failed to get his degree because, in his senior year of 1923, he jumped at the chance to become a full-time reporter for the La Porte, Ind., Herald.

The chance to work in Washington, DC, and the prospect of a raise in pay led Ernie to switch to the Washington Daily News shortly thereafter. The excitement of life in the nation’s capital proved to be the main attraction. The young newspaper man honed his skills in reporting and copy reading.

The paper’s staff was small, so Ernie acquired a wide range of assignments in the newspaper business and developed into a full-fledged newsman. He adopted the life of a typical reporter, working long hours for low pay, drinking a great deal with his cronies, and getting by on a minimum of sleep.

Pyle met and married a civil service worker named Geraldine Elizabeth Siebolds in 1925. It turned out to be a disastrous event for both parties. Jerry, as she was called, made Ernie the center of her life, going along with all of his plans even though they proved to be not only difficult, but often impossible for her to cope with. Ernie, by nature, could not settle down to a single location and a steady job. He wanted to travel, to see the world, and to write about what he saw.

Ernie talked Jerry into quitting her job and joining him on a trip across the country. They had about $1,000 between them. He bought a car for $650, loaded it with camping equipment, and the two started off on their adventure. They circled the whole country, living mostly in the field. Two months later they ended up in New York, tired and broke. Ernie went to work as a copywriter for the New York Evening World. Two years later, on December 26, 1927, they returned to Washington, DC, and Ernie took a job with the Washington News of the Scripps-Howard chain.

Pyle could not settle down to an inside job at the newspaper. He persuaded his managing editor to allow him to travel as a roving reporter, writing six columns a week, with weekly pay of $100. By 1935, Ernie had begun a cross-country drive with Jerry at his side, writing his adventures along the way.

As a roving reporter, Ernie had a folksy style that readers quickly took to. Soon his columns were being carried by other papers in the chain, occasionally at first, but gradually as a regular feature in many of the Scripps-Howard family of newspapers. The travel itinerary to isolated places such as the Aleutian Island chain proved to be too demanding for Jerry. Gradually she gave up regularly accompanying him, and their marriage suffered as a result. She became morose during his absences, turning first to medication and then to alcohol when they were apart.

World War II became the turning point in Ernie Pyle’s career. Initially though, travel to Europe held no attraction for him. A midwestern American, he had a deep-set suspicion of Europeans, foreign languages, and strange customs. As the war grew in intensity his office tried to persuade him to make a trip overseas to report on what was taking place in England. Finally, he consented. Jerry moved back to their small home in Albuquerque, NM, to await his return.

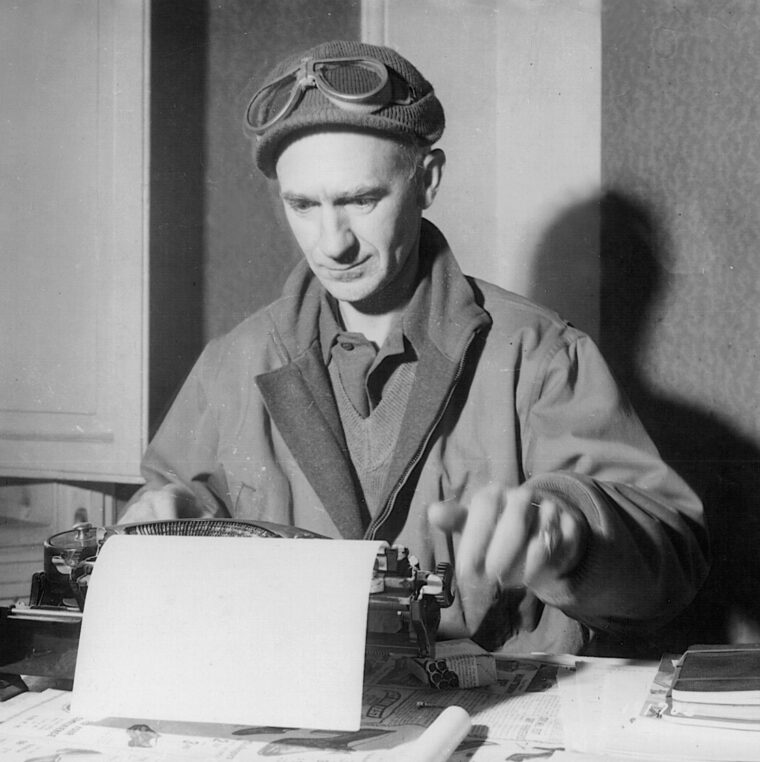

Pyle’s Reputation as the GI’s Reporter Took Off After Following American Landing Forces into North Africa

Ernie began mailing back columns concerning the effects of the German Blitz on London. He reported on the bombings, the fires, and the resulting deaths and damage to the ordinary people and their city. The American public ate up the reports he sent. Pyle’s editor felt that the London stories were the best work he had ever done. Ernie spent three months in London.

Pyle brought the war home to Americans in a manner that had never been previously accomplished. Eleanor Roosevelt, the wife of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, read his columns daily and commented enthusiastically on them in her newspaper column, “My Day.” As a result of this attention, Pyle was becoming famous.

After a brief respite back in the States, Pyle’s increased popularity again led to his being assigned to the European Theater of Operations once more. In November 1942, he followed the American landing into North Africa.

It was at this point that his reputation as the GI’s reporter really took off. It is difficult to describe all of the reasons for his success. He seemed most at home just shooting the bull with infantrymen. He listened rather than talked. He had the ability to capture their feelings on paper, to relate those things that mattered most to his subjects. Whenever possible, when the censors let him, he included the name and the hometown of every GI that he interviewed. In turn, his readers Stateside reacted positively to his style of writing.

Ernie’s columns from North Africa described generally dreary life in the field, the cold hard facts of war—poor food, Africa’s broiling days and freezing nights, the dangers of frontline exposure, and the homesickness and worry felt by the individual GI. Eventually his columns, picked up by an increasing number of newspapers, found their way back to the front, sent by friends and relatives of the soldiers. As time passed, the GIs saw in Ernie a friend who told about their experience in the field the way it really was.

Pyle was soon welcomed everywhere by high-ranking officers on down to the lowliest enlisted man. As the U.S. Army crossed northern Africa, Pyle vividly described the blood of battle—the victories as well as the defeats. He never hesitated to state that he was no hero. He tried to stay out of dangerous situations, seeking to carry the message back home without being killed in the process. Offered the opportunity to fly with bombing missions over enemy territory, he declined, deciding that the risks involved outweighed what could be learned from the experience.

Personally very shy when it came to participating in large gatherings of either troops or civilians, Ernie vigorously avoided any attempt to place him in the limelight. Slight in stature, his health remained borderline throughout his days in the field. He regularly experienced severe headaches and suffered constantly from colds. A heavy smoker, he also drank to excess from time to time when he fell in with old friends. Although he looked for warm and safe places to set up his bases of operation, if his reporting made the exposure necessary, he would also live in the field with the infantrymen he so admired.

On July 20, 1943, Pyle went ashore in Sicily, 10 days after D-day. The Germans and Italians fiercely resisted the landings on the island. The Italian civilians, on the other hand, enthusiastically welcomed the Americans.

Pyle wrote about the Army’s medical facilities. He wanted the people back home to know that the military did everything it could to take care of the wounded. He urged the people on the home front to give blood because it would be used to save the lives of the infantrymen on the front lines. These types of stories helped create the journalist’s reputation as a caring reporter who wanted to let people know what the average soldier was going through.

At the conclusion of the campaign in Sicily, Pyle returned home to the States for a brief break from wartime reporting. Government officials, newspaper organizations, veterans groups, and others constantly besieged him with requests for interviews and speeches on his experiences in Italy. These demands left him little time to spend with Jerry, whose mental health had by this time taken a turn for the worse. Moreover, while in Washington, Pyle had become involved with the wife of another reporter assigned overseas. Both had marital problems, it seemed, and the two found escape in what appears to have been a lighthearted relationship.

Pyle Constantly Faced Death From Enemy Artillery and Heavy Bombings

In mid-December, Pyle returned to Europe and rejoined the American Army on the Italian Peninsula. The troops in Italy were experiencing some of the worst winter weather in the country’s history. They had to cope with fierce German resistance as well as the cold and mud everywhere during the course of their drive north up Italy’s boot.

Despite the dangers involved, Pyle went into the battle at the infamous Anzio beachhead. He constantly faced death from enemy artillery fire and heavy bombing during his stay there. On one occasion, a bomb destroyed the building in which Pyle was sleeping. The concussion from the explosion threw him across the room he occupied, which was reduced to rubble. His rescuers could not believe that he had lived through the attack.

The American public avidly followed Pyle’s reports from the battle scenes. By this time Ernie was recognized as one of the war’s most outstanding front-line reporters. GIs sought him out and considered it a privilege to have the opportunity to talk with him. Pyle never changed throughout his journalistic career; he maintained his low profile approach to reporting, preferring to listen and write rather than to dominate the conversation with the soldiers he encountered. He had an unerring instinct for what made a good story. Both his readers and the GIs themselves came to regard him as a man who could separate the truth, the reality, from the shambles and confusion of battlefield activity. He had no respect for self-important military leaders.

During the Italian Campaign, Pyle wrote a story that came to be ranked among his best. He described the grief felt by a group of infantrymen when the body of their highly regarded company captain was returned from the front line:

“Then a soldier came into the cowshed and said there were some more bodies outside. We went out into the road. Four mules stood there waiting. ‘This one is Captain Waskow,’ one of them said quietly.

“Two men unlashed his body from the mule and lifted it off and laid it in the shadow beside the low stone wall. Other men took the other bodies off. Finally there were five, laying end to end in a long row, alongside the road. You don’t cover up dead men in the combat zone. They just lie there in the shadows until somebody else comes after them.

“The unburdened mules moved off to their olive orchard.

“The men in the road seemed reluctant to leave. They stood around, and gradually one by one I could sense them moving close to Captain Waskow’s body. Not so much to look, I think, as to say something in finality to him, and to themselves.

“I stood close by and I could hear.

“One soldier came and looked down, and he said out loud, ‘God damn it.’ That’s all he said, and then he walked away. Another one came. He said, ‘God damn it to hell anyway.’ He looked down for a last few minutes, and he turned and left. Another man came; I think he was an officer. It was hard to tell officers from men in the half light, for all were bearded and grimy dirty.

“The man looked down into the dead captain’s face, and then he spoke directly to him, as though he were alive. He said: ‘I’m sorry, old man.’

“Then a soldier came and stood beside the officer, and bent over, and he too spoke to his dead captain, not in a whisper but awfully tenderly, and he said: ‘I sure am sorry, sir.’

“Then the first man squatted down, and he reached down and took the dead hand, and he sat there for five full minutes, holding the dead hand in his own and looked intently into the dead face, and he never uttered a sound all the time he sat there.

“And then finally he put the hand down, and then reached up and gently straightened the captain’s shirt collar, and then he sort of rearranged the tattered edges of his uniform around the wound. And then he got up and walked away down the road in the moonlight, all alone.

“After that the rest of us went back into the cowshed, leaving the five dead men lying in line, end to end, in the shadow of the low stone wall. We lay down on the straw in the cowshed, and pretty soon we were all asleep.”

Although Pyle’s main concern was always with the men who did the actual fighting, he did, personally, get to know and admire Generals Dwight D. Eisenhower and Omar Bradley. On the other hand, he had little respect for General George S. Patton, Jr., especially after he learned that Patton had slapped a hospitalized GI whom he had accused of cowardice.

Early in 1944, Ernie joined the host of reporters gathering in England for the anticipated invasion of Normandy. There, he encountered a host of old friends and a flood of correspondence arriving at the rate of 200 letters a week. Many came from infantry Joes whom he had spent time with in Italy. Finally, Ernie accepted help from the Army, which assigned him a public relations officer. It proved to be the only way that he could manage to keep up with the wide spectrum of friends and acquaintances that wanted to hear from him.

During his stay in England, Pyle learned that the Pulitzer Prize Committee had selected him to receive their prestigious award for his 1943 writings. Lee Miller, Ernie’s friend and business agent, had submitted his name. The award came as no surprise to his many fellow reporters.

Ernie’s Fame Skyrocketed, Earning Him As Much as $100,000 in 1944

Although General Bradley offered Pyle a place aboard the command ship, the cruiser USS Augusta, he chose to go ashore on D-day aboard an LST (Landing Ship, Tank) with a hundred or so GIs. He felt that he should tie in with an infantry company, the type of outfit that he had identified with in Africa and Italy.

Once ashore, Pyle wrote of the death and desolation that he encountered on the Normandy beaches. He helped in the cleanup and described the scene facing the crews assigned to the collection of the bodies and the debris left behind.

Ernie accompanied the troops into Paris during the French capital’s liberation and described dramatically the reaction of the city’s citizens to the arrival of their deliverers. Soldiers recognized him and greeted the reporter with cheers and handshakes. Pyle was their friend, and they showed their appreciation for the reporting job he had done.

As his fame spread, Ernie’s earnings from his writing skyrocketed. His salary from the Scripps-Howard chain and the related United Features Syndicate had run about $100 a week before he started reporting on the war. In 1943, his earnings rose to $69,000 annually. In 1944, his income reached $100,000.

Initially, 45 newspapers across the nation carried his column. When he reached his popularity peak in 1945, over 270 periodicals printed his stories. He had become one of the most popular writers in the history of American journalism. The Henry Holt publishing house combined his stories into two books, Here Is Your War and Brave Men. Both became best-sellers.

Hollywood wanted to tell Pyle’s story as well. Work on a film went slowly. Ernie objected strenuously to the producer’s attempts to make him into a hero. While he got to know and like Burgess Meredith, who played Pyle in the movie, the reporter insisted on accuracy from an industry generally lacking in that quality.

Unfortunately, as his fame spread and the demands on his time from every source increased, his wife Jerry suffered more frequent bouts of depression. Living alone in his absence led her to turn to overdoses of prescription drugs and alcohol. Ultimately, she attempted suicide. Jerry survived the experience, but required continuous medical supervision throughout the remainder of her life.

Jerry and some of Ernie’s friends tried to dissuade the reporter from heading to the Pacific. General Bradley, who got to know Pyle well in Europe, told him that perhaps his luck was running out, considering the number of narrow escapes Ernie had experienced in that theater.

The U.S. Navy, however, wanted the reporter to visit the Pacific area. The soldiers, sailors, and Marines needed some of the same attention and recognition in the war against Japan that their brothers-in-arms had received in Europe, the military leaders said. Ernie, although still weary after months of overseas assignments, also felt an obligation to contact many of the troops fighting in the islands of the Pacific.

Premonitions of his death, always troubling for the reporter, increased as he moved to this new theater of war. He reiterated to his friends that if he fell he wanted to be buried with the troops. He, too, felt that his luck was running out.

Once Pyle began his Pacific reporting, he found a different type of war than he had experienced in Europe. The reporter had become a worldwide celebrity, so the Navy gave him that type of treatment. Instead of roughing it in the rain, cold, and mud like he did in Italy and France, he slept on clean sheets and ate in the officers’ mess wherever he traveled. His lack of anonymity made it difficult for him to interview the average GI in the same manner as he had in Europe. The reporter even had a Navy lieutenant commander assigned as his guide.

Pyle did not quickly identify with the troops in the Pacific. The warm weather and better food and living conditions seemed to the reporter to provide a much easier life than the cold and mud of Europe. The biggest problems for the Pacific troops, he felt, were the boredom and isolation that accompanied being stationed on the small Pacific islands.

Ernie ran into a young relative, Jack Bales, serving as a radioman with a B-29 heavy bomber squadron on Saipan. He turned out a series of articles on life among the fliers who were occupied at that time with regular bombing runs over Japan. Ernie wrote about the hazards of the runs and the problem of returning to base over the large open stretches of water. Bales never saw Pyle taking notes, but he turned out reams of copy based on his ability to remember the details of interviews he had conducted with the airmen. Pyle had a fabulous ability to recall conversations, Bales thought.

“At This Spot the 77th Infantry Division Lost a Buddy, Ernie Pyle. 18 April 1945.”

When Ernie finally got aboard a Navy ship, the aircraft carrier Cabot, he again couldn’t help but contrast life aboard ship with the cold and mud of Europe. Moreover, he had trouble with the Navy censors who sought to restrict the reporter’s favorite writing technique, the intimate stories about individual servicemen, including their names and hometowns. The Navy backed down when Pyle threatened to move on to the Philippines, where he expected to get more latitude in his reporting from the Army.

Sensitive to the criticism by some that he had abandoned the troops for life in Navy “officer’s country,” Pyle decided to join the Marines’ operation at Okinawa, the next scheduled Pacific island invasion. Going ashore with the Marines, Pyle once again felt comfortable. They were the type of men he had lived with in Europe.

To the delight of both the Marines and Pyle himself, the initial landings at Hagushi Bay were virtually unopposed. The invasion quickly turned out to be a ferocious struggle, however, with the Japanese losing over 90 percent of their 100,000-man army in the island’s defense. Total American casualties during the Okinawa campaign numbered 49,151. Deaths numbered 12,427, with 4,907 Navy, 4,582 Army, and 2,938 Marine personnel paying the ultimate price.

After a brief respite aboard ship, Ernie went ashore once more with an Army unit charged with clearing the small island of Ie Shima, off Okinawa’s west coast. The Army wanted to take over an airfield there for use in the continuing bombing of Japan. When Pyle and his party landed, the Army personnel already ashore cautioned them to watch out for sniper activity.

While searching for the command post of the Army’s 305th Regiment, the group came under fire. Pyle made the mistake of raising his head at the wrong time. A sniper shot him through his left temple and he died instantly.

They buried Pyle temporarily on the shore of Ie Shima, among the soldiers who had already fallen there. His final resting place is at the National Memorial Cemetery in the Punch Bowl, Honolulu, Hawaii. On the site where Pyle lost his life, the Army’s 77th Infantry Division erected a simple monument to the famed correspondent. The inscription reads, “At this spot the 77th Infantry Division lost a buddy, Ernie Pyle. 18 April 1945.”

The movie, The Story of G.I. Joe, which tells Pyle’s story, premiered on July 6, 1945. Virtually forgotten now, critics at the time considered it one of the most realistic efforts by Hollywood to depict the war as it really was. Jerry Pyle, Ernie’s widow, passed away only four months after the movie’s release.

Dr. Carl Henry Marcoux is a World War II veteran of the U.S. Merchant Marine and a Korean War veteran of the U.S. Air Force. He resides in Newport Beach, California.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments