In the spring of 1944, the Italian Campaign was one of frustration and stalemate for the Allies. General Mark Clark’s Fifth Army had been stymied at Cassino, and strong German defenses barred the gateway to the valley of the Liri River and Rome, the Eternal City and capital of fascist Italy. Three previous attempts to capture Cassino and force entry into the Liri Valley had foundered, and the Allied landings at Anzio had secured a beachhead but had failed to open the way to Rome. Actually, the Anzio effort had just about become a liability. Desperate to link up with the beachhead for a joint push on Rome, General Sir Harold Alexander, commander of Allied ground forces in the Mediterranean, devised an offensive code-named Operation Diadem.

On May 11, 1944, more than 1,600 guns of the Fifth and Eighth Armies commenced a thunderous artillery barrage as the Allies attacked at four different points in the Cassino area. The Polish II Corps, commanded by General Wladyslaw Anders, was given the task of capturing Monte Cassino, the mountain that towered above the town of Cassino, resting on its slope. Atop the 1,700-foot mountain sat the ruins of the ancient Benedictine abbey, which had been reduced to rubble by Allied bombs and subsequently fortified by the Germans.

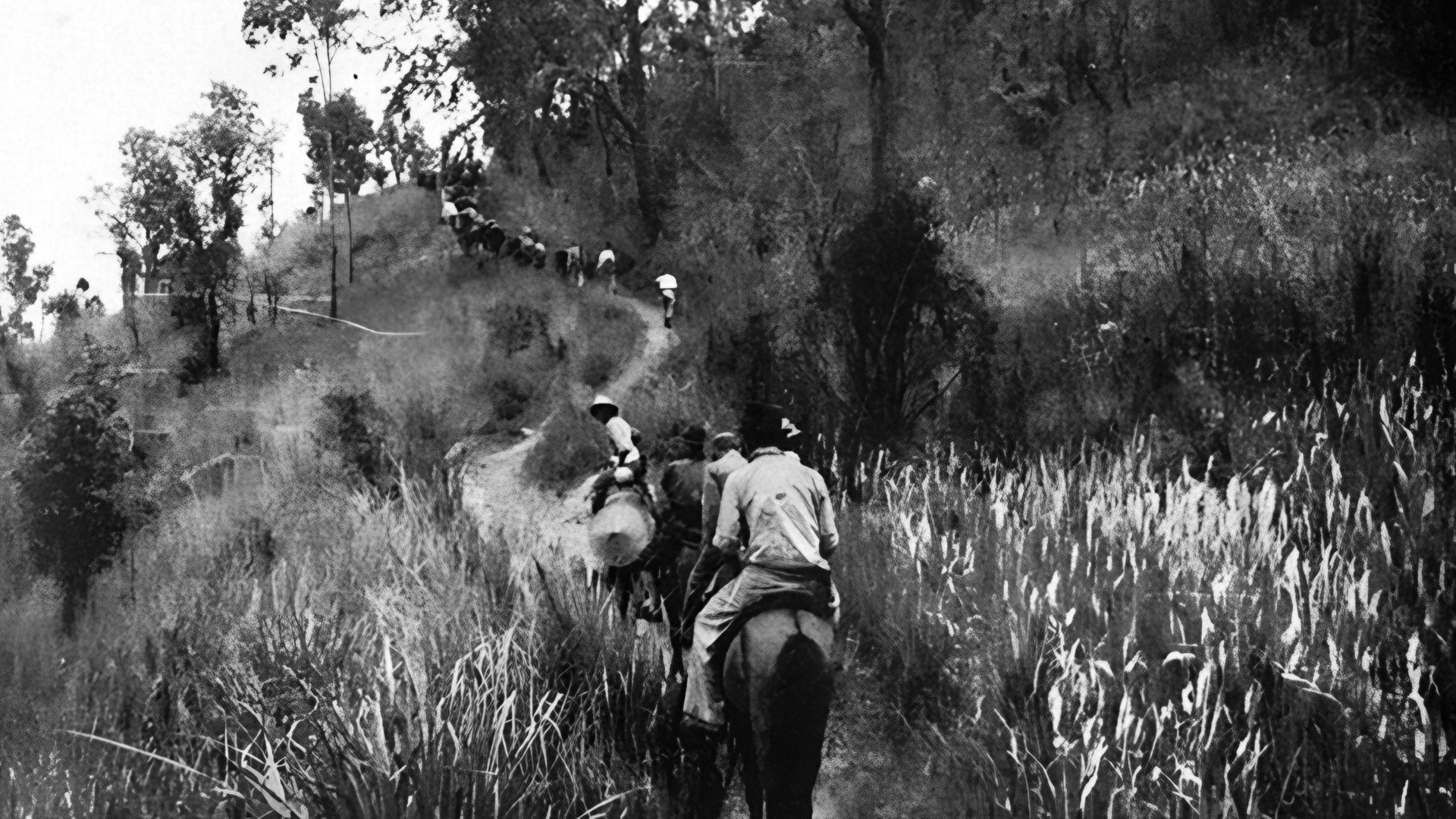

American and Commonwealth forces had come within yards of the ruined abbey but failed to take the position. Now, two Polish divisions, the 3rd Carpathian and the 5th Kresowa, stepped off. The Poles took the Phantom Ridge, 1,800 yards northwest of the abbey, and Hill 593, about 1,000 yards from the Corps objective.

Although they absorbed heavy casualties, the Poles fought on. Theirs was a special brand of determination. Many of them had been taken prisoner by the Soviet Red Army during the early days of the war as the Germans and Soviets partitioned their country. When the Nazis turned on the Soviets and it became necessary for the Soviet Union and the Western powers to fight together, the Poles were released and permitted to form an army. They went to Palestine and then Italy, where they were equipped and continued training with the assistance of the British.

General Anders was himself a veteran of World War I who had fought for his country in the Polish-Soviet War of 1919 and against the Nazis and the Soviets in the early days of World War II. He had been held for months in Moscow’s Lubianka Prison. Anders and the Polish II Corps were fighting for their nation and for their individual honor. They had lost their country and their families. So, they fought like lions against the Nazis.

At dawn on May 12, the Poles found themselves exposed to heavy enemy fire. Half the attacking force had been killed or wounded, and Anders ordered a withdrawal. The Polish Corps mounted its second attack on Monte Cassino on the morning of May 17. The British succeeded in cutting Highway 6, and the Poles took Sant’ Angelo Ridge north of the abbey. Allied aircraft pounded Monte Cassino, and the Germans feared being cut off. That night, under cover of a fierce counterattack, the 1st Parachute Division evacuated Monte Cassino.

The 12th Podolski Lancers reached the abbey on the 18th and found 30 wounded German soldiers and a few medical personnel. The Lancers raised a makeshift regimental standard, and four months of bitter fighting for control of Monte Cassino had ended. Many of the heroic Poles who were killed in the battle for Monte Cassino are buried in a cemetery near where they fell. General Anders, who died in 1970, is buried with them. A simple marker reads:

We Polish soldiers

For our freedom and yours

Have given our souls to God

Our bodies to the soil of Italy

And our hearts to Poland.

It is a fitting epitaph.

Michael E. Haskew

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments