By Michael D. Hull

With such award-winning films as Stagecoach, Young Mr. Lincoln, Drums Along the Mohawk, The Grapes of Wrath, The Long Voyage Home, and How Green Was My Valley behind him, John Ford was one of Hollywood’s most respected directors by the time World War II broke out in 1939.

But 46-year-old Ford, the owner of the Araner, a 110-foot, two-masted yacht, also dreamed of becoming a naval hero, although he had failed the entrance examination for the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis in 1914. He was sure that his country would be drawn into the conflict, offering him his “last chance to be a boy.” He started his naval service several years before the Pearl Harbor attack sent America to war.

After being appointed a lieutenant commander in the U.S. Naval Reserve in September 1934, Ford made periodic cruises aboard his yacht down the coast of Baja California between 1936 and 1939, gathering information for the 11th Naval District. He reported that the crews of Japanese shrimp boats off the Mexican coast were spying and constituting “a real menace” to national defense. He said that there were Imperial Navy officers aboard the trawlers and that the Japanese were familiar with every cove and inlet of the Gulf of California. Ford was commended for his “unselfish and patriotic work.”

John Ford’s Navy

By the autumn of 1939, with Europe now engulfed in war, Ford’s desire to get involved intensified. Garnering a second Academy Award for his Dust Bowl saga The Grapes of Wrath did not deter him. “Awards for pictures are a trivial thing to be concerned with at times like these,” he explained. So, in April 1940, Ford created an unofficial Naval Reserve unit.

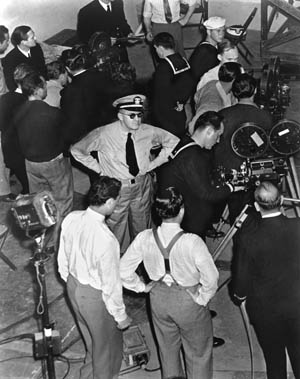

His recruits for the Naval Field Photographic Unit, known simply as Field Photographic, were some of the best talents in Hollywood. They included writers Garson Kanin and Budd Schulberg, cinematographer Gregg Toland, editor Robert Parrish, and special effects expert Ray Kellogg. The unit’s mission was to photograph combat, and Ford hoped that the Navy Department would recognize the value of such a trained auxiliary.

Aided by retired chief petty officer and actor Jack Pennick, a gaunt Marine Corps veteran of World War I and China service, Ford molded the ragtag group into a military force. Its members wore rented uniforms, carried weapons borrowed from the 20th Century-Fox property department, and drilled on a studio soundstage. They learned discipline and even sword drill because “Pappy” Ford, while hating regulations, loved military ceremony. The group became known as “John Ford’s Navy.”

Accepting Field Photographic Into the OSS

The project was not taken seriously by the Navy brass for some months. Ford was ridiculed in some quarters as a “warmonger” and an “over-age Sea Scout,” and his appeals for authorization drew no response. But he was well connected in the Naval Reserve, and he persisted. He lobbied in Washington, and his unit eventually gained official sanction late in 1940. By 1941, with the draft being felt in Hollywood, Field Photographic was deluged with applications.

In September 1941, Ford and his unit members were summoned to Washington where a big surprise awaited them. With the support of Merian C. Cooper, a film producer and colorful soldier of fortune, Field Photographic had been accepted intact—not by the Navy but by the newly formed Office of Strategic Services headed by Colonel William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan, a legendary World War I Medal of Honor winner. Ford was to be accountable to Donovan, who in turn reported to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The unit was assigned an operating budget of $5 million for its first year.

Ford’s unit received its first assignment in November 1941, when Donovan ordered it to produce a filmed report on the U.S. Atlantic Fleet as it helped the British escort convoys and waged an undeclared war against German U-boats. Donovan showed the film to Roosevelt. Shortly after the Pearl Harbor attack, Field Photographic was sent south to film defenses in the Panama Canal Zone.

In February 1942, Ford turned over his yacht to the Navy for use as a patrol craft off the California coast. Many Hollywood luminaries, meanwhile, joined the war effort. Ford’s attractive, elegant wife, Mary, worked at the popular Hollywood Canteen, and his stars John Wayne and Ward Bond served as air raid wardens in Los Angeles.

The Doolittle Raid

American war effort and made the landmark documentary of the Midway fighting in the Pacific.

Impressed with Ford’s North Atlantic and Panama documentaries, Colonel Donovan—backed by FDR—next ordered Field Photographic to film the war in the Pacific, beginning with a top secret report on the Pearl Harbor debacle. The unit started filming in Hawaii, and Ford flew to Honolulu in mid-February to check on progress. While there, he learned of a planned raid against Japan by Colonel James H. Doolittle’s Army Air Forces North American B-25 Mitchell medium bombers from the carrier USS Hornet. Leaving Toland in charge of the Pearl Harbor film project, Ford and several cameramen managed to talk their way into joining Vice Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr.’s Task Force 16, formed around the Hornet, so that they could cover the launching.

Ford sailed aboard the heavy cruiser USS Salt Lake City. On the morning of April 14, 1942, four days before Doolittle’s 16 bombers lifted off the Hornet, Ford was proud to learn from the cruiser’s radio that he had won his third Academy Award for How Green Was My Valley, the poignant story of a Welsh coal mining family.

But the irascible, hard-drinking filmmaker, who liked to be called Jack, was angered when he returned to Hawaii and learned that the Navy had confiscated Toland’s Pearl Harbor film and locked it in a vault because it was considered controversial. The high-strung, depressed Toland was assigned to the Field Photographic station in Rio de Janeiro, and Ford headed for Washington.

Field Photographic Goes to Midway

During a brief stay in the hot, muggy capital, Ford was told by Donovan that something big was imminent in the Pacific. Navy cryptographers had breached Japanese codes and learned that the Imperial Navy was trying to provoke the U.S. Pacific Fleet, still weak after the Pearl Harbor attack, into a confrontation around remote Midway Atoll, 1,304 nautical miles northwest of Hawaii. Donovan asked Ford to fly out and film what might be the most important naval battle of the Pacific War.

The filmmaker did not hesitate. In mid-May, he flew in a Douglas C-47 transport to San Francisco and boarded a destroyer for his four-day return to Pearl Harbor. Then, Ford and Jack MacKenzie, a photographer’s mate, rode a Navy patrol plane to Midway. Circling the tiny atoll after a four-hour flight, Ford peered down and saw that its small Marine and Navy garrison was braced for action. Sandbags were piled, slit trenches dug, machine guns positioned, and ground crews bustled around fighter planes on the airstrip.

Ford sensed the resolve of Midway’s defenders and was in high spirits. “This is some place, really fascinating,” he wrote to his wife on June 1. “The morale here is extremely high, and the food is really delicious—best I’ve had in the Navy.”

When a Midway-based patrol bomber sighted the powerful Japanese fleet on the morning of June 3, 1942, Midway’s Marine battalion and sailors took last minute defense measures. As more emplacements were hastily dug, fighters fueled, and ammunition belts distributed, Ford and MacKenzie got ready to film the inevitable attack.

Filming the Battle of Midway

On Thursday, June 4, the two-day Battle of Midway—the most decisive naval engagement since Trafalgar—began as dive bombers and torpedo bombers from the U.S. carriers Hornet, Enterprise, and Yorktown, led by Rear Admirals Frank Jack Fletcher and Raymond A. Spruance, sought out and attacked Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s four carriers, Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu.

On Midway itself, Pappy Ford and the red haired, freckled MacKenzie took their positions with hand cameras and waited tensely. Ford climbed the airfield’s wooden control tower and sent MacKenzie to Midway’s generating plant. Ford advised the young man, “Photograph faces. We can always fake combat footage later.” They did not have long to wait.

At dawn on June 4, before Ford had dressed, Midway came under attack. Waves of Japanese carrier bombers and fighters roared in, bombing and strafing. Explosions shook the atoll, debris flew, and a fuel dump belched smoke and flame. Though feverish and with their hearts pounding, Ford and MacKenzie calmly captured on film the fury around them—incoming enemy planes, bombs falling, fires, leathernecks firing machine guns, weary American fighter pilots returning, medical corpsmen carrying bodies to ambulances, and smoking wreckage.

On the control tower, Ford was both terrified and exhilarated when Japanese fighters zoomed in and riddled the structure. One of the planes came so close that Ford saw the pilot give him a toothy grin. At 8 that morning, the filmmaker aimed his camera at a group of Marines hoisting the Stars and Stripes while smoke and flame swirled in the background. The dramatic shot eventually became one of the best known images of World War II.

As Ford descended from the control tower, a close hit by an enemy plane stunned him. Then he realized that he was bleeding. Shrapnel had splintered his left forearm. He sought medical attention and then continued to film the attack and devastation. The filmmaker was later awarded the Purple Heart and a citation from the 14th Naval District recognizing his “courage and devotion to duty.”

In the close-run naval battle, meanwhile, American carrier planes had sunk the four enemy flattops and scored a costly but momentous victory. Yamamoto abandoned Midway invasion plans, and his shattered fleet retired westward. The Imperial Navy had been put on the defensive in the Pacific.

“Hollywood’s Own Personal Hero”

Ford spent several days photographing Midway’s damage before quietly collecting his footage—eight cans of color film—and sailing to Los Angeles aboard a transport ship. He had a rush print made of the Midway film and found himself being hailed as a combat hero. A Hollywood Reporter headline announced on June 18, “Ford Filmed Battle of Midway,” while columnist Louella Parsons gushed that he “is Hollywood’s own personal hero.”

The filmmaker flew on to Washington and arrived at OSS headquarters unshaven and with his left arm bandaged. He went to work immediately on the Midway footage with editor Parrish. Ford wanted no official interference and suspected that Navy brass and censors might come “snooping around,” so he ordered Parrish to fly to Hollywood and work on the film there.

Parrish assembled the film on the 20th Century-Fox lot. Screenwriter Dudley Nichols wrote a narration, which was rewritten by Jim McGuinness of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Ford flew out when the project was ready. The narration was recorded by Henry Fonda, Jane Darwell, and Donald Crisp, three of Ford’s players, and the director watched a screening of the rough cut in a locked editing room while a Marine stood watch outside. Ford regarded the 18-minute documentary, titled The Battle of Midway, as a timely morale booster. “It’s for the mothers of America,” he declared. “It’s to let them know that we’re in a war and that we’ve been getting the s—- kicked out of us for five months, and now we’re starting to hit back.”

Donovan and the director rushed the film to the White House, where it was promptly viewed by the president, his wife, Eleanor, trusted adviser Harry L. Hopkins, and Admiral William D. Leahy, FDR’s senior naval aide. The footage included a shot of Marine Corps Major James Roosevelt attending a memorial service for the Midway dead, and when the president recognized his son, he fell silent. After the viewing, the first lady wept and FDR was ashen. Turning to Leahy, the president said, “I want every mother in America to see this picture.”

Twentieth Century-Fox distributed 500 prints to theaters across the country, and the first public screening was at New York’s Radio City Music Hall on September 14, 1942. Editor Parrish reported, “It was a stunning, amazing thing to see.… City women screamed, people cried, and the ushers had to take them out.… The people, they just went crazy.”

Ahead of its time, the Ford film was propagandist yet realistic and inspirational and showed that an Allied victory in the Pacific was possible. The Battle of Midway was widely seen and critically acclaimed and eventually won the Academy Award for best documentary short subject of 1942.

Cameras Rolling on Operation Torch

Immediately after the White House screening, Ford flew to London in a Pan American flying boat with Pennick, now his unofficial aide. The purpose was to organize Field Photographic crews for Operation Torch, the upcoming Allied invasion of North Africa. Ford sent his camera crews to the British Commando School at Achnacarry in the Scottish Highlands for special training and conditioning.

The complex invasion was launched on November 8, 1942, with three Allied task forces converging on the Morocco-Algeria coasts. Thirty-four thousand U.S. troops landed near Casablanca; 39,000 British and U.S. troops went ashore near Oran, supported by airborne troops; and 33,000 men landed near Algiers. Pappy Ford waited in Gibraltar, impatient to get to the front.

As soon as permission was granted, he left Gibraltar on November 14 with Pennick and photographer’s mate Robert Johannes. They commandeered a jeep in Algiers and attached themselves to D Company of the 13th Armored Regiment in Major General Orlando Ward’s 1st Armored Division. The regiment advanced to the Algerian port of Bone, where Ford spent several days with Hollywood producer Darryl F. Zanuck. Driving a requisitioned Chevrolet coupe and armed with a Tommy gun, two pistols, and hand grenades, the diminutive Zanuck was covering the war for a documentary and a book.

Ford and his 32 cameramen saw plenty of action in Algeria and Tunisia. Huddling in foxholes and sharing the risks and hardships of the tankers and infantrymen, they survived German artillery, machine-gun fire, and dive bombers. Ford lost 32 pounds while subsisting on tea and hard English biscuits.

Capturing a German Pilot

One day in Tunisia, while D Company was under attack by German bombers and dive bombers, Ford, Pennick, and Johannes took refuge in a grove of eucalyptus trees. A flight of Royal Air Force Supermarine Spitfires swooped to attack the enemy planes, and Ford had his camera ready to film the fierce dogfight that ensued. He watched a Spitfire shoot down a twin-engine Junkers Ju-88 medium bomber, and a crewman bailed out.

As the parachute billowed and drifted down, Ford shouted to his companions, “Come on! Let’s take him prisoner.” The three Americans jumped into their jeep and careened across wadis and scrubland to where the German had landed. He surrendered, told Ford that he was the bombardier, and asked to be taken to where the plane had crashed to see if any others of the four-man crew had survived. Ford agreed.

But the smoking wreckage yielded three charred bodies. While the bombardier mourned his friends and Ford pondered what to do with him, a Free French Army lieutenant drove up and demanded jurisdiction over the German. Ford turned him over, and the Frenchman began slapping the captive while interrogating him. Ford intervened, saying, “OK, that’s enough! The prisoner stays with us.” The French officer was enraged, but Ford stood his ground and eventually turned over the airman to the company commander. The German was not aware that the humane American who had captured him was a famous Hollywood director.

December 7th

After their six hectic weeks in combat, Ford, Pennick, and Johannes flew to Gibraltar in December 1942, and then headed home aboard the attack transport USS Samuel Chase. Ford, who had been promoted to captain in the U.S. Naval Reserve, then spent several months in Washington busying himself with his film unit and lobbying high-ranking officers and Congressmen. But he grew bored, so he decided to resurrect footage of the Pearl Harbor disaster by Toland and Navy cameramen. Parrish trimmed the footage to half an hour, Budd Schulberg wrote the narration, and Alfred Newman, one of Hollywood’s leading composers, wrote the score. The documentary was titled December 7th.

As part of the Industrial Incentives Program, the film was not released to theaters, but was shown in defense plants to boost production and morale. Producer Walter Wanger told its director that December 7th was a “great picture” and a “triumph,” and it received an Academy Award for best documentary of 1943.

Ford in the CBI Theater

Ford continued globetrotting and his association with Colonel Donovan. In the summer of 1943, while the latter was getting the OSS established in the China-Burma-India Theater, the tireless filmmaker flew to New Delhi to oversee work on a new documentary, Victory in Burma. The film would focus on the theater commander, Lord Louis Mountbatten, and the long, bitter struggle waged against the Japanese in the Burmese jungles by General William Slim’s “forgotten” British 14th Army. Ford flew reconnaissance flights to China, photographed air raids in Burma and China, and worked closely with Maj. Gen. Albert C. Wedemeyer, the theater commander of U.S. forces, and Maj. Gen. Claire L. Chennault, leader of the U.S. Fourteenth Air Force and the legendary Flying Tigers.

After a wearying seven-day flight from New Delhi, Ford and Pennick arrived home in January 1944. Called into Donovan’s office, Ford was praised for his efforts in the Far East, told that he had been a great asset to the OSS, and was recommended for promotion to captain. Donovan then informed him that his Field Photographic would be in charge of filming the planned Allied invasion of Normandy. The filmmaker was both stunned and jubilant.

John Ford Meets John Bulkeley

Captain Ford flew to England early in April 1944 and busied himself for the next two months getting his film unit ready to cover the invasion. Mark Armistead’s Field Photographic team in London had been hard at work for 18 months photographing the European coast from low-flying B-25 bombers and gathering data on French waters, beaches, and inland terrain. One of Armistead’s prime sources on the Normandy shore was his friend, Lieutenant John D. Bulkeley, the commander of a PT-boat squadron in the English Channel.

“Buck” Bulkeley had gained fame as a daring PT-boat skipper in the doomed Philippines early in 1942 and for evacuating General Douglas MacArthur and his family from Corregidor. Bulkeley was awarded the Medal of Honor, and his feats were celebrated in William L. White’s bestselling book They Were Expendable. Ironically, Pappy Ford was under Hollywood pressure from April 1943 onward to turn the book into a film, but he felt he could not leave Field Photographic and that the war was more important. Screenwriters McGuinness and Frank W. “Spig” Wead kept up the pressure, but Ford resisted, saying that he was “committed to a major operation.”

One spring morning shortly before the Normandy invasion, Ford was resting in his room at London’s elegant Claridge’s Hotel when there was a knock on the door. It was Armistead and Bulkeley. Although he was naked, the filmmaker jumped out of bed, stood at attention, and saluted the PT-boat hero. “I’m proud to salute the man who rescued General MacArthur,” he declared. Bulkeley regarded Ford as eccentric, but the two soon became firm friends.

Five Days Aboard Bulkeley’s PT-Boat

On the night of June 5, 1944, after dispersing his camera crews among the Allied assault groups, Pappy Ford went aboard the heavy cruiser USS Augusta, the flagship of Rear Admiral Alan G. Kirk’s Western Task Force. Too excited to sleep, Ford paced the decks that night as the Augusta and the rest of the Allied armada butted through the choppy English Channel toward France. When the historic early hours of Tuesday, June 6, 1944, came, the filmmaker peered through binoculars as the British, American, and Canadian armies started landing across five Normandy beaches.

He saw the high bluffs behind Omaha Beach and the murderous German crossfire that pinned down elements of the U.S. 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions there for several critical hours on D-Day. The Augusta was some distance offshore, and Ford grew restless; he wanted to get close to the action. So he sent a radio message to Armistead, who was aboard Bulkeley’s PT-boat, and told him to come and pick him up. The boat duly eased alongside the cruiser, and Ford was swung aboard in a boatswain’s chair.

Bulkeley briefed the filmmaker on his boat’s operations, which had included ferrying undercover agents in and out of Normandy and which now centered on beachhead patrols and keeping German U-boats away from the Allied ships. Ford enjoyed himself for five days aboard the PT-boat, standing watch on the cramped bridge, getting a ringside taste of combat when the craft skirmished with enemy E-boats off Cherbourg, and growing to admire the gallant, unassuming Bulkeley. He told Ford frankly that his service in the Philippines had been exaggerated in White’s book, that he had received too much publicity, and that he had not deserved the Medal of Honor.

The five days with Bulkeley convinced Ford that the hero’s story could be told on the screen and that he was the one to direct it. Vacillating no longer, he said, “I frankly admit that I am getting as enthusiastic as hell about They Were Expendable.”

They Were Expendable

Two weeks after the Normandy landings, the bulk of Ford’s film unit sailed home. The weary director checked into a New York hotel, slept for 12 straight hours, and then headed for the West Coast. After agreeing to produce and direct They Were Expendable for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, he summoned writers McGuinness and Wead and put them to work on the script. Wead, an early record-breaking naval aviator before being partially paralyzed in a staircase fall, had penned screenplays for many films about the Navy, including Dirigible, Hell Divers, Ceiling Zero, Submarine D-1, Dive Bomber, and Destroyer.

Ford went on detached duty from the Naval Reserve in October 1944, and he and Wead honed a final script, focusing on the PT-boat squadrons that fought delaying actions against Japanese invaders in the Philippines early in 1942. It was a saga of gallant sacrifice in the face of heavy odds. Shooting on the film began around Key Biscayne, Florida, early in February 1945. The Navy loaned MGM several PT-boats and their crews, and Biscayne Bay stood in for Manila Bay in the action scenes.

The director chose boyish actor Robert Montgomery to portray the lead character, Lieutenant John Brickley, based on Bulkeley. Ford had to arrange for the Navy to release Montgomery from duty. Montgomery had commanded a PT-boat in the Solomon Islands, served on a destroyer off Normandy, and been decorated. Brickley’s brash executive officer, Lieutenant Rusty Ryan, was played by John Wayne, who said, “Jack was awfully intense on that picture and working with more concentration than I had ever seen. I think he was really out to achieve something.” Although he revered Ford, Wayne was regularly bullied on the set by Ford until Montgomery stepped in on his behalf. The film’s supporting cast included Donna Reed, Ward Bond, Jack Holt, Pennick, Marshall Thompson, and Leon Ames.

“Poet With a Camera”

Because of the Japanese surrender in September 1945, MGM delayed the release of the film until the following December. Its world premiere at Loew’s Capitol Theater in Washington on December 19 was attended by many Hollywood and military luminaries, including Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. Moving and sometimes poetic, They Were Expendable was critically acclaimed. Nation magazine reviewer James Agee called it “so beautiful and so real.” But audiences were limited because filmgoers had grown tired of war stories, and the powerful imagery of Ford’s creation was not generally appreciated for several years.

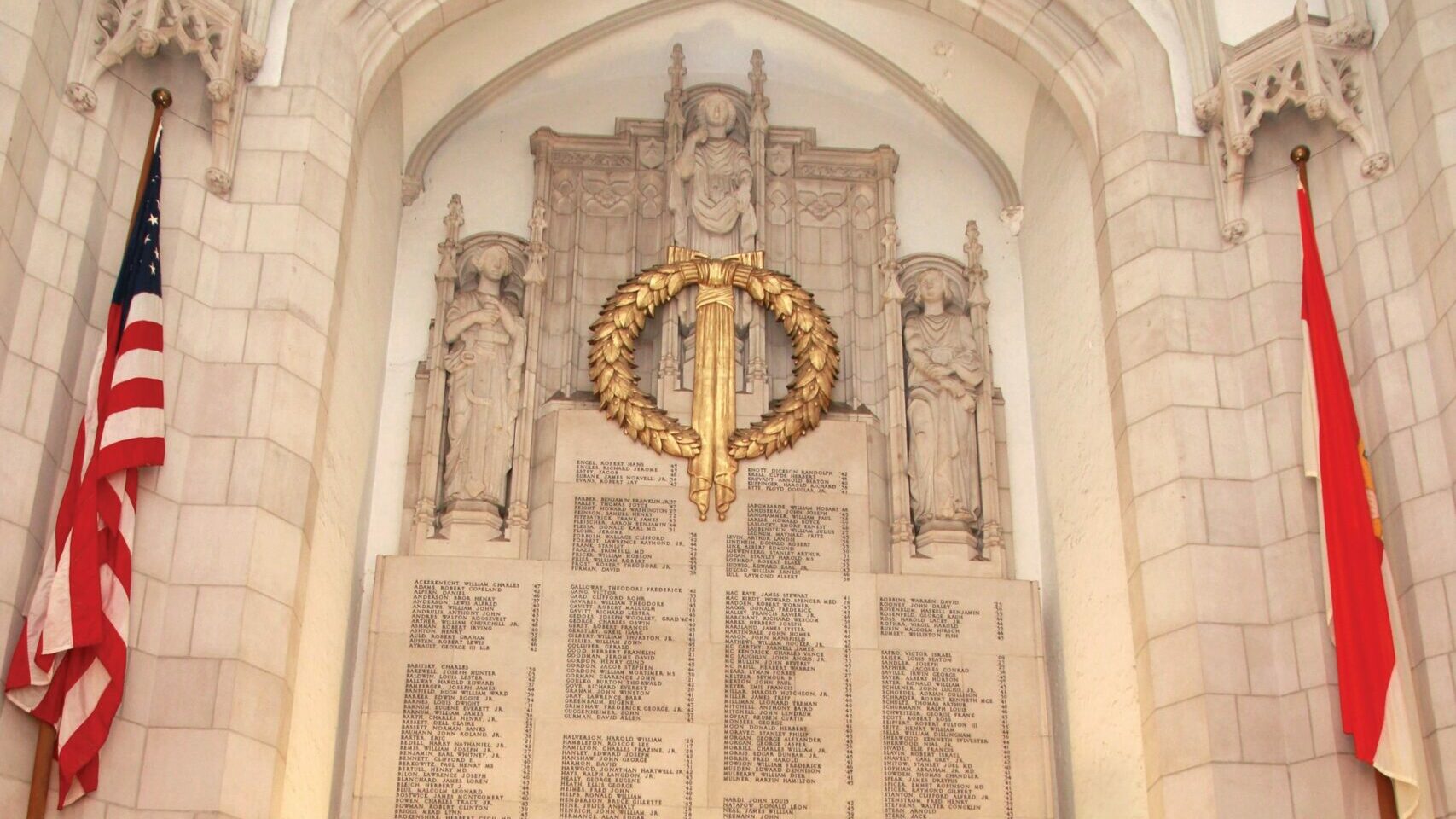

The producer-director, meanwhile, remained active with Field Photographic and Colonel Donovan despite his failing health. While his film unit aided the OSS in gathering evidence about Nazi war criminals, Ford oversaw the disbanding of Field Photographic and purchased an eight-acre tract near Encino, California, where a recreation retirement center was established for the 180 cameramen who had served under him. Donovan pinned the Legion of Merit on the “poet with a camera” in September 1945.

In the postwar years, Ford was best known for a string of screen masterpieces about the American West, but he also directed four more documentaries, including two about the Korean War and two more films about the Navy. These were the comedy-drama, Mister Roberts, starring Henry Fonda and James Cagney, and the biographical The Wings of Eagles, with John Wayne portraying Ford’s longtime friend Spig Wead.

Pappy Ford retired from the Naval Reserve with the rank of rear admiral in 1951. Five months before he died of cancer on August 31, 1973, he was awarded the Medal of Freedom by President Richard M. Nixon. At his funeral, Ford’s coffin was draped with the frayed American flag he had filmed being hoisted by Marines at Midway.

Good to read this, I was looking for some record of the memorial for Ford’s photographers. As a neighbor we boys of the Reseda, Erwin Street neighborhood, got to swim in the estate pool, got to see Henry Fonda, John Wayne, Harry Carey Junior and Senior, and listen to the bagpipers every memorial day; and ride some of the estate burro’s, and let some of the horses munch on our abundant volunteer alfalfa. It was a lot of fun. One of the boys saved a woman from drowning in the pool with her enfant child. I like to believe Ford and his men were an inspiration.

D. Hutton

This has some of the best information that I have read on John Ford and others.

My Dad was in Ford’s unit. The stories were amazing to hear.

The Farm was so much a part of my life.

My great-uncle Joseph August was an Academy nominated cameraman and the founder of the A.S.C. He was also good friends with John Ford–even back to the days of Thomas Ince and Frances Ford! Joe was a member of the OSS with John Ford and was on John’s yacht often. I did find a photo that was in the newspapers about John Ford and cameramen (naming Joseph August) in the summer of 1941 as these people being in the Naval Reserve. I believe they had been preparing for sometime for what was yet to come!

This is a wonderful article. I am a history teacher and have been interested in the life of John Ford for many years. I have a question, maybe someone who sees this can give me an answer. Was John Ford ever on the USS Hornet? Did his crew ever film the Doolittle raid?