By William H. Langenberg

By early 1779, the American Revolution had been under way for more than three years, with no end in sight. That January, the British high command in London conceived a new military strategy designed to supplant its twice-failed attempt to sever New England from the rest of the American colonies. The new strategy envisioned taking the fight to the two Carolinas and Georgia, where southern loyalists and friendly Indians would provide valuable support for Great Britain’s powerful army and navy.

To execute this strategy, British leaders concluded that another military base had to be established on the northeastern coast of America, between Boston and the Canadian border. This new bastion would serve three important functions. First, it would provide the British Navy with an operating base to guard the Bay of Fundy and protect Nova Scotian shipping from harassment by New England privateers. Second, it would block an overland American attack on Nova Scotia from the west. Most important—or at least imaginative—the new base would provide a sanctuary for loyalists driven from the rebelling colonies. It would be called New Ireland.

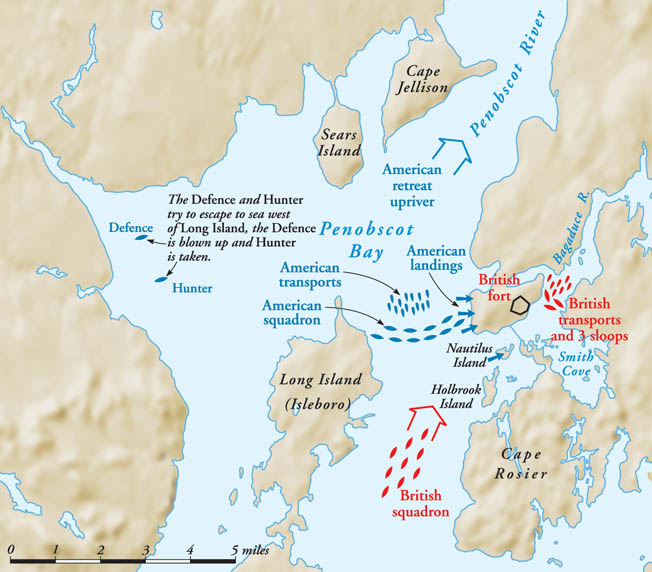

Fort George and Penobscot Bay

The British decided to establish the new base at Penobscot Bay in the province of Maine, then part of the Massachusetts colony. Accordingly, the high command ordered General Sir Henry Clinton, commander in chief of British forces, to execute the assignment. Clinton in turn tasked the British governor of Nova Scotia, Brig. Gen. Francis McLean, to establish the new post, taking sufficient troops to defend themselves during the construction process. McLean was a veteran soldier, a 62-year-old bachelor who had participated in nearly 20 battles in Europe and Canada. He selected Captain Henry Mowat as his naval commander. Mowat was an experienced British Navy skipper, having helmed the man-of-war Canceaux for several years, patrolling the waters of New England and Nova Scotia.

McLean, commanding nearly 700 British troops, left Halifax, Nova Scotia, for Penobscot Bay on May 30, 1779. His six transport vessels were escorted by six warships, one of which, Albany, was skippered by Captain Mowat. Proceeding slowly against prevailing southwesterly winds, the convoy arrived at Penobscot Bay on June 12 and promptly began off-loading troops and supplies. McLean selected a favorable high site on Bagaduce Peninsula to construct a defensive fort, one that kept the Penobscot River between any future American attackers from the west and the new British bastion. The area around the fort was thinly inhabited by American colonists, many of whom had become impoverished by the British navy’s blockade off the coast. Limited by topography, harsh climate, and rocky soil, the colonists’ farming income was scant. Given their deprived economic status, McLean was able to hire nearly 100 of them to help clear the land and build the new redoubt, dubbed Fort George.

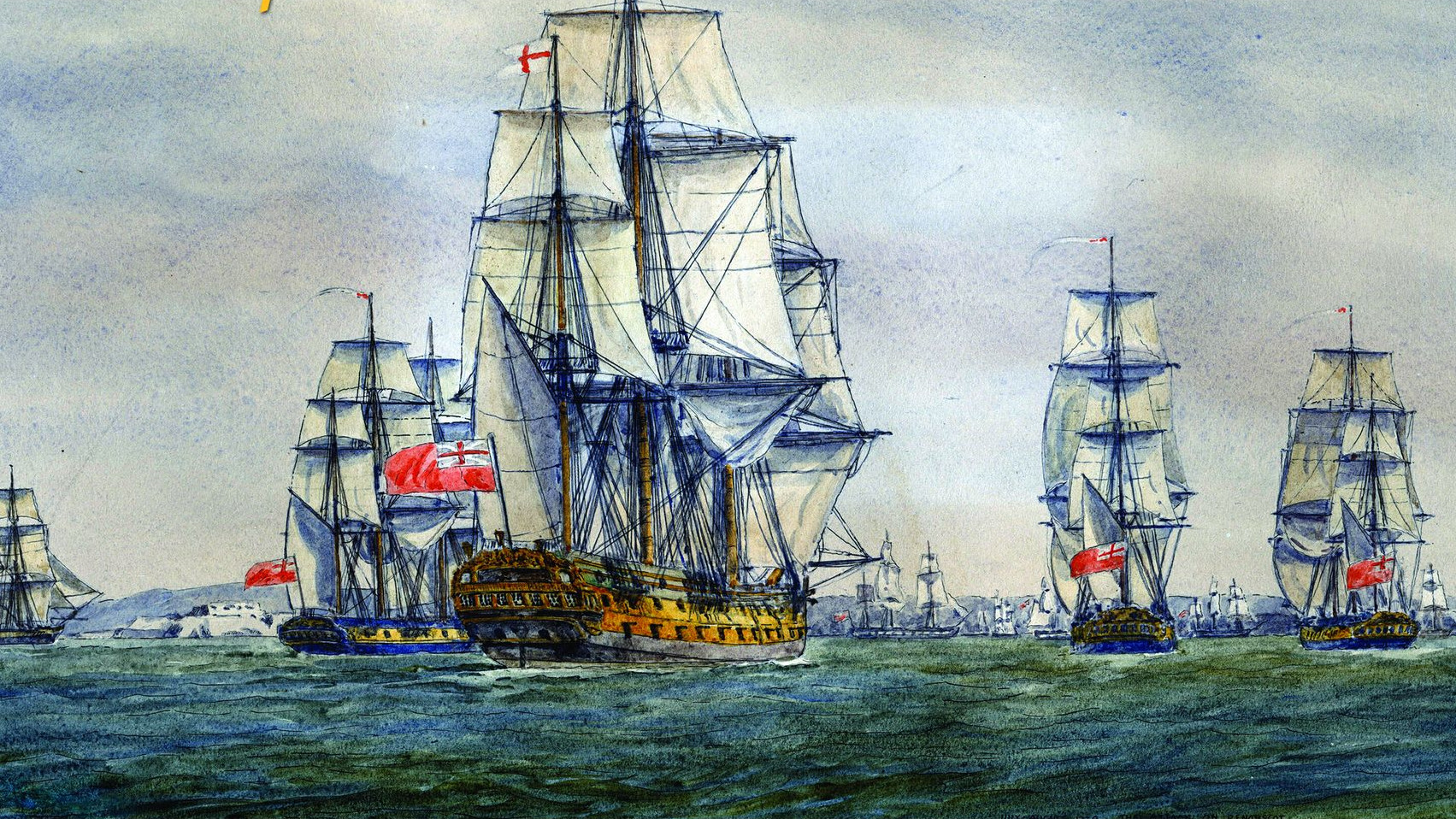

Meanwhile, Mowat persuaded McLean to retain three British warships to help defend the fort during the course of construction. The sloops Nautilus and Albany, with 18 guns each, and North, with 30 guns, remained in Penobscot Bay while the remainder of the warships returned to duty elsewhere in July. Mowat anchored his sloops in line across the entrance to the inner harbor to defend against an American attack. The three ships had spring lines attached to their anchors so that they could turn in place to present their broadsides to an approaching enemy. With his ships in position, Mowat sent sailors ashore to help the army troops and civilian laborers construct the fort and emplace its cannons.

The Penobscot Expedition

On July 18, McLean received information that the Americans were raising an expedition to evict the British invaders. Priority was given to placing gun batteries in position for immediate defense against an American incursion. Mowat believed the intelligence was valid, and he sent 180 more seamen ashore from the three ships on July 20 to help finish construction of the fort. The next day, McLean requested troop reinforcements from General Clinton in New York.

While McLean’s invading force at Penobscot Bay labored diligently to prepare defenses at the new fort, urgent American countermoves were under way in Boston. News of the British landing had arrived on June 23, while the General Court, Massachusetts’s legislative body, was in session. Already badgered by pleas for assistance from residents of Penobscot Bay, the court took prompt action, directing that a naval force be organized and sent to the bay to drive out the enemy before they became entrenched. Creation of the naval force was facilitated when private owners of nine armed sailing vessels volunteered their services. This initial cadre was soon augmented by three Massachusetts colony brigs and three Continental Navy warships then anchored in Boston harbor

.

The General Court labored feverishly to organize and equip the naval force, now known as the Penobscot Expedition. The court impressed ships, supplies, militia, and seamen into service. Privateering was common in New England, and armed ships were readily available. Since potential crew members could not expect to match their often lucrative income from privateering, manning the vessels proved to be more difficult. Another challenge was choosing commanders for the sea and ground forces. On July 1 the General Court appointed Massachusetts Brig. Gen. Solomon Lovell, a fellow politician, to command the troops. Lovell had served as a junior officer in the French and Indian War and remained in the militia afterward, advancing in rank to colonel. He became active again in the Revolutionary War and was promoted to brigadier general in 1777.

Two days after selecting Lovell, the General Court appointed Captain Dudley Saltonstall, skipper of the Continental Navy frigate Warren, then anchored in Boston harbor with 32 guns, as commander of the Penobscot Expedition’s burgeoning armada. Saltonstall had served in the American merchant fleet before becoming captain of the letter-of-marque brigantine Britannia during the French and Indian War. When Congress created the Continental Navy in 1775, he was the senior among five captains appointed. During the war he had commanded the flagship Alfred, the frigate Trumbull, and a Connecticut privateering sloop before becoming Warren’s skipper. Saltonstall was well qualified by maritime and combat experience to lead the sea forces to Penobscot Bay. The court, having appointed leaders for both the shore and sea arms of the expedition, failed to designate an overall commander. This omission, almost guaranteed to create uncertainty and vacillation during subsequent combat operations, went unnoticed and uncorrected.

The Weaknesses of the Expedition

On July 19, still lacking seamen and supplies, Saltonstall got under way in Warren, accompanied by his local forces. Saltonstall’s armada sailed to Townsend, Maine, where it was joined by three more privateers, additional transports, and militia personnel. On July 24, the entire task force set out for Penobscot Bay, 60 miles to the northeast. Included in Saltonstall’s fleet were 40 vessels—18 armed warships or privateers and 22 schooners or sloops serving as troop transports. Together, they comprised the largest American fleet yet assembled during the Revolutionary War.

As formidable as the armada seemed, it had several shortcomings. To begin with, most of the 900 officers and enlisted men were militia soldiers from Massachusetts or Maine, augmented by 300 Continental marines. Fully 500 more militia conscripts failed to report at Townsend, nearly one-third of the number ordered to do so. Untrained as a unit, few of the men in the expedition had any experience in making an amphibious landing on a hostile shore. Likewise, the 18 armed warships, mounting 334 cannons and augmented by three colonial vessels and 12 privateers, had no prior training together as a fleet. Even worse, the privateers had no military experience acting under orders from a fleet commodore.

Capturing the Battery on Nautilus Island

Undaunted or unaware of its weaknesses, the armada formed up to enter Penobscot Bay on Sunday, July 25. Saltonstall sent the brig Diligent ahead to reconnoiter Bagaduce Peninsula and the British fort under construction there. Captain Philip Brown, aboard Diligent, scanned the still-incomplete fort with his long glass and noted one British artillery battery on Nautilus Island and Mowat’s three anchored sloops of war positioned to defend the bay. Reporting back to Saltonstall, Brown urged him to attack immediately, but Saltonstall favored caution. He refused to lead his ships into the inner harbor, which he termed “a damned hole,” because Penobscot Bay was sometimes subjected to tides of more than 10 feet, which produced strong currents both into and out of the bay. In addition, light or variable winds inside the sheltered bay made maneuvering difficult for large sailing vessels, particularly square-rigged ships such as Saltonstall’s own flagship, Warren.

Taking all proper precautions against such nautical hazards, Saltonstall sailed his fleet into Penobscot Bay, arriving opposite Bagaduce Peninsula at 2 pm on July 25. He ordered the shallow-draft transports to proceed farther up the Penobscot River and drop anchor while his armed vessels shelled the three anchored British sloops, now showing their broadsides to the approaching Americans. For the rest of the afternoon, the British and American vessels exchanged long-distance, sporadic gunfire, with negligible damage inflicted by either side. Concurrently, Lovell attempted to land troops on the west side of the peninsula, but aborted the effort owing to high winds.

The next day the Americans attacked a different target. Some 200 marines landed and captured the British gun battery on Nautilus Island. But militia soldiers again attempting to land on the west coast of Bagaduce Peninsula were repulsed. Throughout the night, the Americans strengthened their captured battery on Nautilus Island, building a breastwork facing the British fort across the narrow channel and installing three cannons in the redoubt. During the same period, crafty Captain Mowat repositioned his three British sloops farther inside the harbor so that they were no longer threatened by the American battery on the island. In their new anchorage, however, they could not effectively oppose American troop landings on the peninsula.

Mowat’s Close Integration of Land and Sea Forces

The following morning, the American brig Pallas shelled Mowat’s three stationary sloops, scoring some insignificant hits, and sailors from Saltonstall’s vessels replaced the marines who had captured Nautilus Island, establishing a new battery on its highest point. Concurrently, a petition signed by 32 captains and officers from the Massachusetts colony’s ships and privateers was presented to Saltonstall, urging an immediate attack on the three British sloops inside the harbor. Saltonstall did not respond. Meanwhile, Lovell prepared for a night landing on the precipitous western side of Bagaduce Peninsula by his marines and militia.

The new landing began at dawn on July 28, following shore bombardment by the American vessels Tyrannicide, Hunter, and Sky Rocket. Troops landed successfully on the rocky beach; they were led by Lovell and Brig. Gen. Peleg Wadsworth, together with colonels in command of marine and militia units. Clambering with difficulty up the steep slope in the face of intense musket fire, the Americans drove British forces off the high ground and forced them to retreat into the fort. Lovell then ordered cannons emplaced on the newly captured high ground of the peninsula, from which point they could shell the still-unfinished Fort George. Of the 350 attacking Americans, 34 were killed or wounded. Lovell dispatched a report on his progress to the General Court by small boat and horseback.

Capture of the British artillery battery on the crest of Bagaduce Peninsula permitted American warships to move closer to the inner harbor entry. In a rare display of initiative, Saltonstall led three American vessels toward Mowat’s three anchored sloops. Handicapped by light northwest winds, Saltonstall could only bring Warren’s bow guns to bear. He turned his ship broadside from his target, receiving for his trouble the worst of a subsequent exchange with Fort George and the British sloops and suffering damage that required two days to repair. The painful skirmish only added to Saltonstall’s reluctance to engage the enemy in a climactic attack.

Meanwhile, British defenders girded diligently for a renewed American assault. McLean created a light-infantry unit containing 80 men to harass the American positions on Bagaduce Peninsula. Mowat moved his sloops farther into the inner harbor, then ordered all but one of his transports to be beached and burned, thus precluding possible escape of British forces by sea. The one remaining transport, St. Helena, was fitted with six guns and added to Mowat’s anchored defensive line. Again demonstrating close cooperation with British land forces, Mowat sent most unengaged guns from his four vessels to Fort George, along with enough sailors to man them.

Attack by Land and by Sea

Still, Saltonstall temporized about launching a new attack on the British ships. He called a council of war aboard Warren, one of several indecisive meetings to decide the fleet’s future actions. Unsurprisingly, the privateer skippers feared excess damage to their ships unless the American land forces could first destroy all opposing British artillery batteries. The only decision reached was to site more cannons in the American battery on the crest of Bagaduce Peninsula to fire on Fort George and the British Half-Moon battery protecting the harbor.

On July 30, sporadic gunfire raged onshore between the British and American gun emplacements. That afternoon, the American galley Lincoln arrived in Penobscot Bay with dispatches from the General Court urging Saltonstall and Lovell to proceed with vigor to expel the British forces. The messages also warned both leaders of the likelihood of the enemy being reinforced. Recognizing the possibility of just such reinforcements, Saltonstall already had assigned the brig Diligent to act as a lookout at sea to warn of approaching enemy ships. He now added the brig Active and the sloop Rover to the scouting team stationed offshore.

To placate the expedition’s privateer captains, Saltonstall and Lovell organized a joint land-sea attack. On Sunday, August 1, the American ship Sky Rocket commenced shelling the British battery, and Lovell’s ground forces attacked via land. British sailors and marines stationed on the peninsula returned fire briskly. The American militia broke and ran, but Lovell’s marines surged ahead, surmounted the breastworks, and forced the British defenders to retreat to the fort. The next morning, however, the British counterattacked and regained the battery, dislodging the marines. Lovell sent a message to the General Court stating somewhat optimistically that he had placed Fort George under siege and complaining about problems with the unreliable militia troops under his command.

“Attack and Take or Destroy”

The repulse sparked Saltonstall to revise his strategy. Reasoning that the British could not be ejected from the seemingly formidable Half-Moon artillery battery, he opted to join Lovell’s siege. As a first step, Saltonstall sought to establish battery sites on shore that could bring Mowat’s four ships under fire. He placed one such site at the northeast corner of the inner harbor, and Lovell manned the two artillery pieces with militia, hoping to keep the marines available for future assaults against the British defenses. The battery began firing ineffectively at maximum range against the four anchored British ships on August 4.

Neither Saltonstall nor Lovell seemed to question whether they had adequate time for an effective siege. Lovell did not dare attack the British fort directly until Saltonstall’s fleet had neutralized the defending ships and battery. Conversely, Saltonstall did not consider it prudent to attack Mowat’s vessels without a concurrent land assault. An impasse had developed within the Penobscot Expedition, resulting in the postponement of any decisive action. Such delay could prove disastrous if formidable enemy reinforcements suddenly appeared on the horizon, borne by British warships.

Reacting to the American siege, British leaders feared that communications might be severed between Fort George and Mowat’s sloops in the harbor. To make such an occurrence more difficult, Mowat commenced construction of a shore redoubt on the peninsula between his ships and the fort, manned by 50 seamen serving eight cannons removed from his vessels. On the American side, Lovell planned an escape route for his troops in case reinforcing British warships trapped them inside Penobscot Bay. On August 5, he requested that Saltonstall enter the harbor with his warships and demolish Mowat’s defending vessels so that an American land attack could begin against the fort without fear of being decimated by the British ships.

In response to Lovell’s request, Saltonstall held another temporizing council of his ship captains, the majority of whom asserted that such a course of action would result in excessive damage to the American fleet. Saltonstall reiterated his reluctance to take Warren into “the damned hole” of the harbor. Lovell held a concurrent council with his land-force leaders, who concluded that it was impracticable to support the fleet under present circumstances. He forwarded the minutes of the meeting to Boston. Upon receipt of Lovell’s report, the General Court directed Saltonstall “to attack and take or destroy [the British ships] without delay.”

“Inexpertness and Want of Courage”

On August 7, Saltonstall convened a joint conference for land and sea leaders aboard Hazard. There, he proposed two alternative actions. First, the expedition could “strike a bold stroke, by storming the enemy’s work and going in with the ships.” Alternately, the siege could be lifted—the first time such an option had been raised. Lovell maintained that his troops were in no shape to storm Fort George without reinforcements. Saltonstall countered by saying that the fleet would be unable to mount a successful attack without incurring excessive losses, explaining that impressed seamen among his ships’ crews were deserting in increasing numbers. No participant at the conference was yet ready to raise the siege or concede that the assigned mission should be abandoned. The conference, like its predecessors, resulted in no decisive action. In the meantime, powerful British naval reinforcements were under way toward Penobscot Bay from New York, under the command of Vice Admiral Sir George Collier.

To augment the expedition’s siege, Lovell commenced construction of a new artillery battery on a site selected by Salstonall. At the same time, Mowat’s British sailors, aided by soldiers supplied by the supportive McLean, completed their seamen’s redoubt and armed it with eight light cannons from the British ships. On August 9, Saltonstall apparently learned for the first time that the Bagaduce River was deep enough to permit his ships to sail up it nearly two miles northeast of the fort. This was crucial information since it would enable a practical assault plan to be implemented. Why Saltonstall had not already sent a shallow-draft boat or ship upriver to take soundings is unclear. As a result of the revelation, he finally obtained an agreement from the majority of his ship captains to attack the four anchored British ships—provided that American land forces conduct a concurrent diversionary assault on the fort. A decision was reached to launch a coordinated attack the following morning.

The belated joint attack was again postponed. Although Saltonstall sent 120 marines to bolster Lovell’s force, skirmishes with the British Army on August 11 convinced Lovell that his militia forces, plagued by continuing desertions, were inadequate to confront the enemy owing to their “inexpertness and want of courage.” The next day, Lovell halted construction of the new battery and issued orders to transfer additional heavy guns to the American transports. Meanwhile, American fishermen and settlers on the west side of Penobscot Bay sighted unidentified vessels offshore in the sea fog.

Arrival of the British Armada

The next morning, yet another council of war was held aboard Warren. Lovell again reversed his position and agreed to another immediate attack. That afternoon, he sent 400 troops ashore to storm the rear of the British fort. At the same time, Saltonstall brought five ships into the harbor, led by Putnam. At the time, the wind was light from the southwest, with a beginning flood current—ideal conditions for the delayed climactic assault. Almost immediately the attack was aborted after Diligent sailed into the harbor with four warning flags flying from her masthead. The long-dreaded British reinforcements had appeared on the scene. The mysterious vessels reported the previous day shrouded in fog were now identified as six heavily armed British warships. They included the flagship Raisonable, with 64 guns, plus the 32-gun frigates Blonde and Virginia, 28-gun Greyhound, and 20-gun Camilla and Galatea.

Upon learning of the arrival of the British armada—which still included far fewer guns and ships than his own fleet—Saltonstall immediately broke off the belated assault and anchored his five vessels in the bay, forming a defensive crescent together with other American warships. He sent a note to Lovell recommending that he withdraw and retreat up the Penobscot River in the waiting transport vessels. Lovell concurred, and by dawn most of the American troops were aboard or en route to their transports waiting on the river bank. As the transports filled, they were towed offshore to await the expected flood current.

Losing All Ships

Just after dawn on August 14, a final council of war was held aboard Warren. Although some ship captains recommended attempting to escape to sea around the west side of Long Island, Saltonstall decided to flee with the flood current up the Penobscot River, explaining that “the risk of engaging the British was too great” to set out to sea. By now, 21 heavily loaded American transports were rowing or floating slowly upriver. Lovell, in charge of the transports while the British warships were becalmed in the lower harbor, turned over command to Wadsworth, tasking him with locating a new site upriver to fortify and defend while the Americans burned or scuttled their vessels and their crews retreated into the woods. Lovell then took a boat to Warren to urge the American fleet to engage the British warships and gain time for the transports to land upriver and set up a defensive position. Saltonstall informed him in no uncertain terms that he was merely waiting for sufficient wind to proceed upriver and scuttle his vessels.

Meanwhile, Mowat prepared to unite his warships with the reinforcing squadron led by Collier. Taking aboard a light-infantry unit supplied by McLean, who anticipated an American defensive stand somewhere up the Penobscot River, Mowat weighed anchor and moved his three sloops into the bay. Shortly thereafter, Saltonstall signaled all American ships to “shift for themselves.” The rout was under way. As the British frigates Blonde, Virginia, and Galatea drove the American ships before them, only one ship returned fire. The privateer Hampden, skippered by doughty Captain Titus Salter, simultaneously engaged Blonde and Virginia until she was forced to strike her colors. American privateers Hunter and Defence attempted to escape the British attackers by sailing around the west side of Long Island, but Hunter was driven ashore on the west bank of the bay and Defence was scuttled in Stockton Springs Harbor.

The remaining American vessels fled the oncoming British warships by sailing, rowing, or drifting up the Penobscot River. Hazard, with Wadsworth aboard to locate a site upriver to establish a defensive redoubt, unwittingly contributed to the rout by sailing past the slower transports without offering any assistance. This spread panic among the fleeing troops, and many of the vessels were grounded and burned in Mill Cove, along the west bank of the river, and their crews and soldiers fled ingloriously into the woods.

During the flight, Saltonstall’s Warren went aground on a shoal and was stranded until the next high tide. Just after dawn on the 16th, the remaining American transports and warships were set on fire, while Saltonstall off-loaded stores from the Warren and ordered his flagship burned as well. Wadsworth, coming ashore with his troops, discovered to his horror that only about 40 enlisted men remained willing to fight, the remainder having fled into the woods. Wadsworth took the remaining officers and men and headed back to Boston on foot. Lovell opted for a different route. Despite having led a successful landing on Bagaduce Peninsula, Lovell was reluctant to return to Boston without more tangible successes to report to the General Court. He headed north with several officers to make a treaty with the Penobscot Indians to prevent them from allying with the British. In this, at least, he was successful.

The Scapegoats of the Penobscot Expedition

The Penobscot Expedition was a total fiasco. Without exception, all the American vessels were captured, scuttled, or burned by their masters. Ironically, the privateer captains who previously had worried about excessive damage to their ships if they attacked the British wound up destroying their own precious vessels. American sailors and soldiers who had fled into the woods without food or supplies were forced to embark on a four- to six-week trudge through unforgiving wilderness back to Boston, where they were received as something less than conquering heroes. Total American losses included 16 warships burned and two captured, 13 transports burned and nine captured. British sources claimed 474 American casualties, against 70 suffered by the defenders.

In the end, three British sloops mounting 56 guns and a small garrison of troops had withstood a 21-day siege by an American fleet and army several times their strength. Adverse consequences were immediate. The Massachusetts colony’s navy was obliterated, while the Continental Navy lost one of its newest and most formidable warships in Warren. Perhaps more lasting, the colony’s indebtedness incurred to finance the Penobscot Expedition proved a crushing burden for years in the future, and the humiliating defeat left a lasting stigma upon most of those involved in its creation and execution.

Upon receiving news of the ignominious defeat, the General Court began a prompt search for scapegoats. A special court of inquiry unanimously concluded that Generals Lovell and Wadsworth had acted with “proper courage and spirit” throughout the expedition and retreat, but that Commodore Saltonstall had been “want of proper spirit and energy.” Two weeks later, Saltonstall was court-martialed aboard the frigate Deane in Boston harbor and summarily cashiered from the Continental Navy.

Saltonstall was not the only senior leader of the expedition to suffer disgrace as a result of his performance. Lt. Col. Paul Revere, the legendary patriot who had ridden through Boston warning “the British are coming!” before the battles at Lexington and Concord, was also implicated in the debacle. Having led the artillery train on the Penobscot Expedition under Lovell, Revere was relieved of command and placed under house arrest shortly after returning to Boston. Serious charges of misconduct, including “disobedience of orders and unsoldierlike behavior tending to cowardice,” were lodged against him by Marine Captain Thomas J. Carnes and Brig. Gen. Peleg Wadsworth. In November 1779, an inquiry board found Revere guilty of culpable behavior. Displeased with the outcome, Revere petitioned the General Court to convene a court-martial. After several delays, the court-martial was finally held in February 1782. The court acquitted Revere “with equal honor as the other officers in the expedition”—hardly a glowing restoration of his reputation. His accusers refused to retract their charges, resulting in continued unseemly public debate played out in issues of the Boston Globe.

It was not until nearly a century later, in 1863, that Revere reassumed his position in the pantheon of Revolutionary War heroes. That year, beloved poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, the grandson of Revere’s former accuser, Peleg Wadsworth, published the adulatory poem “Paul Revere’s Ride,”memorized by generations of American schoolchildren. By then the Penobscot Expedition, perhaps the most ignominious defeat in the long, proud history of the American Navy, had faded from memory. As President John F. Kennedy, himself a Massachusetts native, noted in another context in 1961, “Victory has a thousand fathers, but defeat is an orphan.”

Being from Maine, I find it hard to accept such blunder by the Patriots.

Thank you for the education.

It highlights the myths of the American Revolution.

To the professional British, they were scoundrels and cowards. Paul Revere was such, he should have been shot. Instead, dumb Americans consider him a hero.

Yes. And funny how that worked out in the end!