By William McPeak

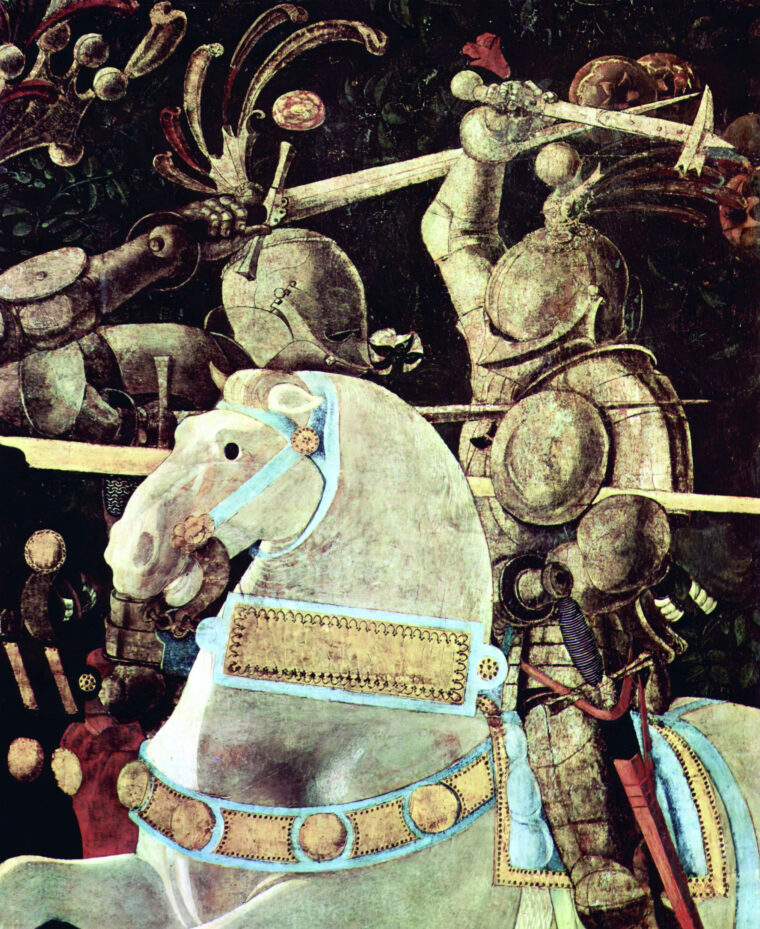

Not to be confused with Mjollnir, the mythical Norse god Thor’s fabled hammer, the real-life war hammer was a brutal and effective weapon. The development of the war hammer began around the middle of the 14th century and mirrored the advance in combat protection—specifically, plate armor. Advances in mesh and chain mail already had prompted the greater popularity of hafted weapons such as the battle-ax and the mace. But when armor started being formed into riveted plates in the mid-14th century, followed by contoured sections that presented a curved, glancing surface against sword strikes, concussion weapons were given a long second look.

A Means of Penetrating New Armor

The advances in armor showed in the improvement of weapons to counter them. Longer shafts provided greater torquing force and a more powerful hit for two-handed weapons. Simple metal-ball and faceted-head maces changed to massive iron-flanged heads with projecting lugs that became progressively more pointed. These advances were meant to inflict crushing blows to helmets and armor. But armorers reciprocated by forging surface-hardened steel for armor. The result was significant. Surface-hardened steel was essentially as hard as a sword or ax edge, meaning that a single blow—perhaps the only chance one would get in the heat of battle—was more likely to skip off the surface than to puncture it. Armor wearers had acquired greater survivability.

The hammer, as a basic tool for manual labor, was of ancient origin, but like the axe it quickly became an early peasant weapon as well. A large-headed mallet, war mallet, or maul—the latter made of wood or lead—came to be used on the medieval battlefield. The true war hammer first appeared in the late 14th century, as evidenced by manuscript illustrations and battle histories of the time. Massed graves excavated from the Battle of Wisby in 1361 revealed many skulls with small square punctures that could only have been made by early war hammers. Similarly, at the Battle of Roosebeke in 1382, Flemish peasants with good basinets were significantly outnumbered by French royal troops and paid a heavy price, as noted by the great French chronicler Jean Froissart: “So loud was the clashing of swords, axes, maces and iron hammers on those Flemish basinets that naught else could be discerned above the din.”

By the beginning of the 15th century, the iron hammer-like head was two inches square and secured to a shaft 25 inches long, similar to that of a battle-ax or mace. It was primarily a horseman’s second weapon, with a leather thong tied to the base of the shaft so that it could be carried at the saddle. (The war hammer had better odds of delivering a full- force blow when traveling downward.) Its smaller surface area made for a concentrated point of impact. It could not puncture the better armors or helmets, but it could put a dent into them that would render the occupant temporarily stunned, vibrating inside the helmet upon impact. A few more speedy blows might be in order, but a forceful first blow sometimes was all that was needed to do the trick.

Advancements in War Hammer Designs

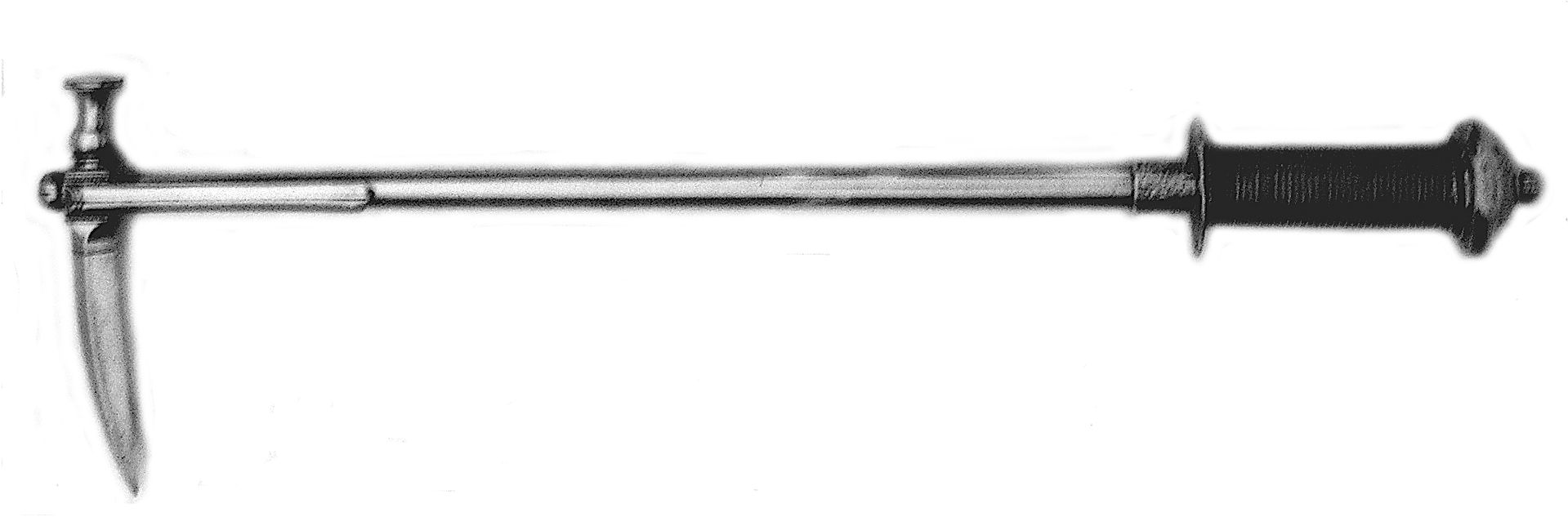

Puncturing was a logical follow-up. Most war hammers from the later 14th century had an extension to the opposite end of the hammerhead as a counterbalance in the form of a short, thick blade. By the early 15th century, this was further developed into a slightly down-turned pick, initially about six inches long. The pick also began appearing at the rear of the battle-ax, giving users the option of a second blow for penetration, a fast turnaround hit to softer armor parts such as the neck or underarms, or even a strike at the light-armored breastplate. With a smaller point of impact, a forceful blow could pierce the armor. The pick could also be used as a hook to grapple at armor, reins, or shield.

About 1450, the hammerhead was given a short, vertical spike that could be turned toward armor weaknesses. Like the battle-ax, the hammerhead’s wooden shaft was often reinforced with riveted metal bands, called langets, to prevent an opponent from cutting the weapon in half with a sword. War hammers were similarly equipped. Soon, all-metal shafts became standard for knightly axes, maces, and war hammers.

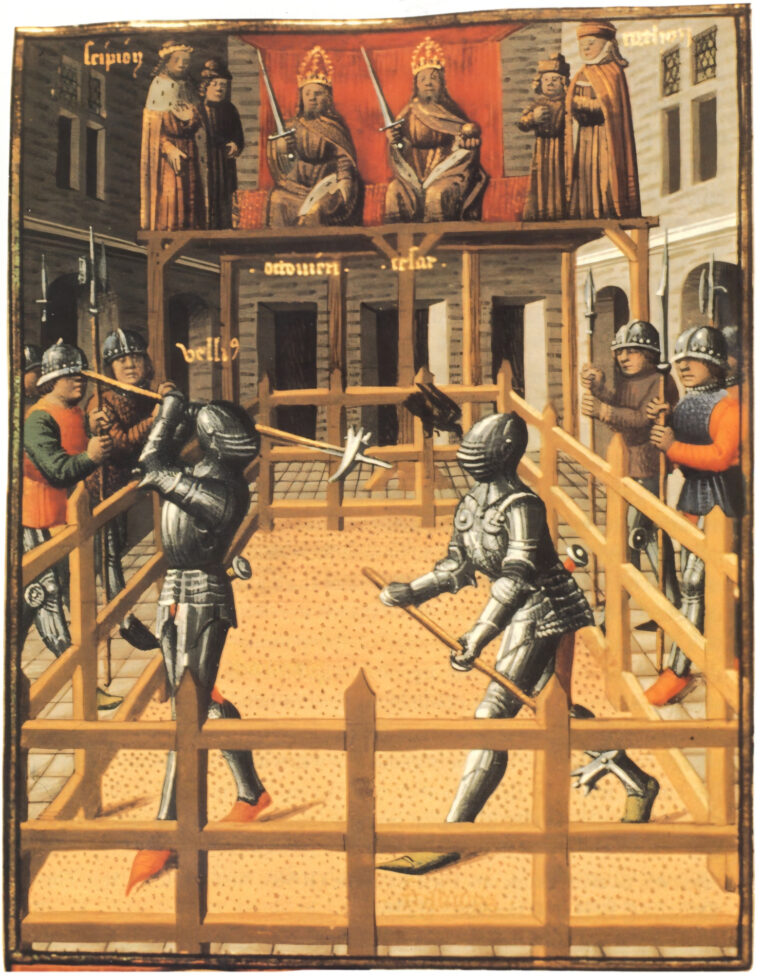

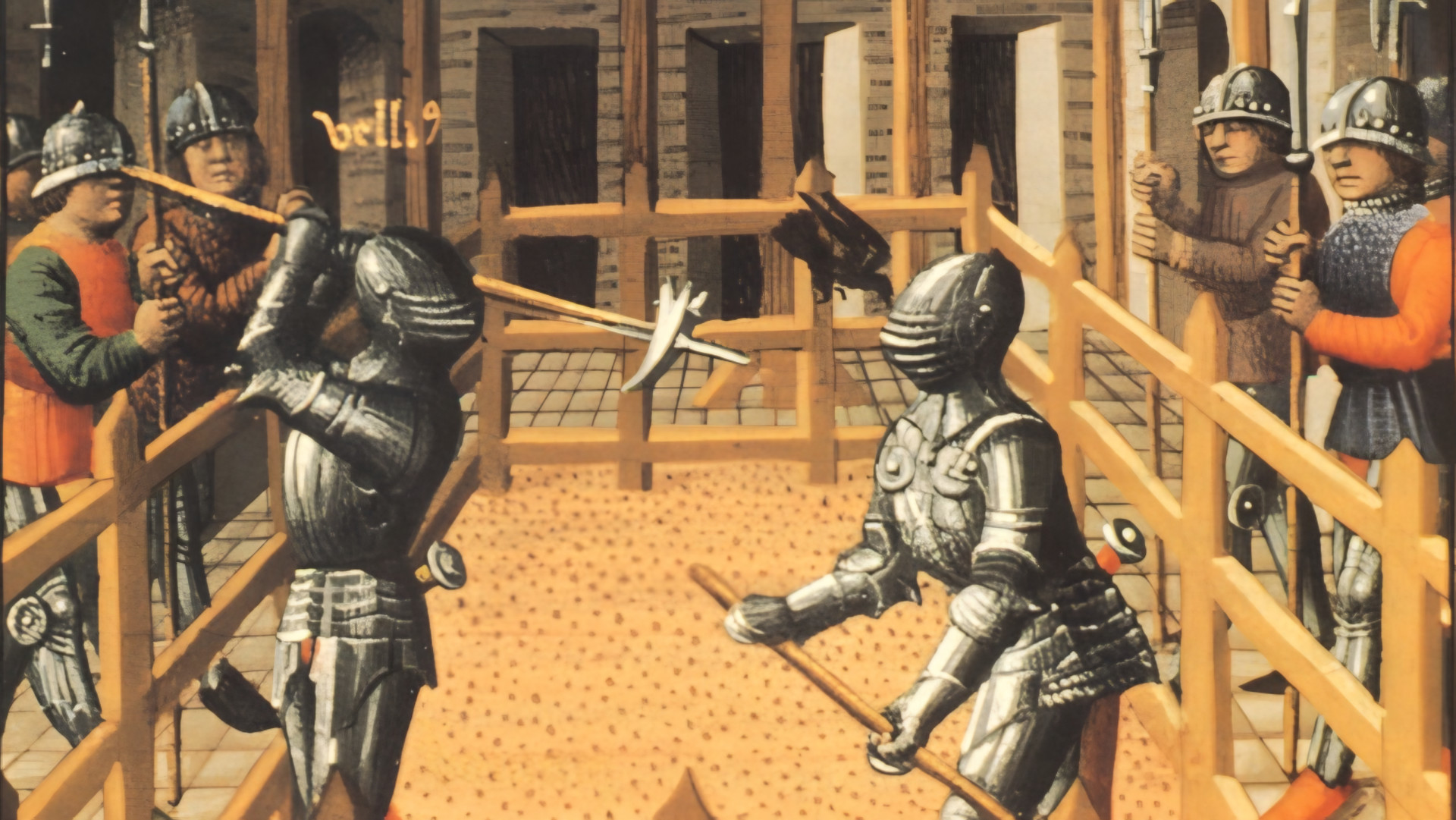

Originally, the war hammer was a knight’s weapon used against other mounted knights. But for the infantryman, already availing himself of various long polearms, the lighter war hammer was increasingly a weapon of choice in the struggle with mounted men-at-arms. Additions to the war hammer kept coming. A longer shaft made for an even more effective blow to the helmet. The pick was also more effective as a hooking instrument with the longer shaft. The addition of a top spike added spearlike functions: grappling armor, reins, shields, or turned point-blank as a heavy blow to pierce even heavy armor. Against mounted opponents, the weapon could be directed at toppling the armored foe to the ground, where he could be more easily vanquished.

The Lucerne Hammer and the Bec de Corbin

With the various one- and two-hand war hammer styles, their characteristics took on special names. The Lucerne hammer was an adaptation by the ever-inventive Swiss, who had proved their mastery of the halberd at the Battle of Sempach against Austrian Imperial forces in 1386. The Lucerne hammerhead was split into a three- to four-pronged head and mounted atop a seven-foot shaft. It bore a longer pick and an even longer and thinner spike coming out of the top of the head. The hammer provided for several smaller points of impact with a more forceful bite. And the longer form made it a very effective “man catcher” for dismounting riders.

Then there was the bec de corbin, old French for “crow’s beak.” Unlike the Lucerne hammer, the bec de corbin was used primarily with the pick, or beak, for attack. The hammer was usually the typical blunt face instead of the multi-pronged Lucerne. The beak tended to be stouter, longer, and better designed for tearing at armor, while the spike was shorter so as not to interfere with the beak’s purpose. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has a basinet thought to have belonged to Joan of Arc, with a deep dent—near penetration—on the left cheek, the work of a bec de corbin.

The bec de corbin became a catchall name for other types of war hammer, such as the bec de faucon, or “falcon’s beak.” Another was called the horseman’s pick, a type of cavalry war hammer with a long pick curved downward similar to a miner’s pickax, but thinner. It was used as a means to penetrate thick armor or chain mail, but it was relatively heavy, making it unwieldy and easily avoided. An interesting weapon parallel to the bec de corbin was the Persian and Indian war pick, or “crow’s bill,” that featured an elaborate thick and sharp pick (beak) and was developed independently as the use of chain mail and armor became widespread in the 17th and 18th centuries in those eastern regions.

In western Europe, the war hammer continued to be a modestly popular secondary weapon into the 16th century, mainly for cavalry. In the same period, the pike had become the prime polearm weapon, whereas the various forms of poleax—including the larger war hammer variety—were relegated to use by special guards. The increasing use of accurate and potentially armor-piercing longarms from the late 15th and 16th centuries spelled the doom for armor technology.

By the early 17th century, the trade-off of cavalry speed and agility over heavy frontal armor was considered far more practical. An important factor in the relinquishing of armor was that the chance of being hit by musket fire was low—even for the first rank of attacking cavalry. The vast majority of standard longarms were smoothbores, rendering shot accuracy more or less random. The war hammer, long since displaced in its initial purpose against armor, enjoyed a resurgence of interest as a concussion weapon against the trend in lighter armor in western Europe.

The Polish Hussars’ Hammer

The case of the war hammer in eastern Europe was very different. There, lighter armor was more the norm, and the war hammer became a favorite secondary weapon of the light cavalry known as hussars, a name initially referring to mounted bandits but later meaning light cavalry mercenary lancers who migrated into southern Hungary when the Turks invaded Serbia at the end of the 14th century. The hussars proved their effectiveness on the battlefield against the Turks and were incorporated into Hungarian king Matthias Corvinus’s so-called Black Army in the mid-15th century. After the king’s death in 1490, many hussars moved on to Poland to fight against the Tatars. There they found a permanent home in the Polish light cavalry. By the middle of the 16th century, the integrated Polish hussars made up twice the contingent of traditional fully armored knights—many of whom became hussars themselves. Indeed, the nobility forged the backbone of hussar companies.

By the end of the 16th century, the hussars had adopted enough armor to become a new, more agile heavy cavalry, using their trademark 18-foot light-long lance as their initial shock weapon. They sported breastplate, a mail shirt, forearm guards, thigh armor (cuirass), and an open-faced burgonet-like helmet called a zischaage. Total weight of a hussar’s armor was no more than 30 pounds. An animal-skin mantle, particularly leopard, was a showy form of identity and esprit de corps. Perhaps the most notable element of the latter array was the famous “wings” the hussars would sometimes wear—eagle wings attached to arching frames and a special support on their back armor or saddle. The rush of these wings during a charge was psychologically unnerving, and the extra height they gave riders was intimidating.

The war hammer was the hussars’ most common secondary weapon. Slung from the saddlebow, the early Polish hussar war hammer was of German and Italian design, with a long shaft. Two styles had names derived from Turkish. The czekan was a combination of hammerhead on one side and an ax on the other. The nadziak, perhaps the most popular war hammer, had a hexagonal head balanced by a long, slightly drooping beak.

The Polish obuch was similar and became, in time, popular as a walking stick. Polish nobles carried war hammers like civilian swords—and evidently used them as such, for protection or dueling. As a consequence, private-use war hammers were banned as too dangerous in 1578, 1601, and 1620. Although heavy fines were charged for carrying them except in war, the fad of using them for civilian protection continued into the 18th century.

Polish Hussars at the Gates of Vienna

By 1600, Polish hussars had bested all other cavalries thrown against them. Each hussar unit charged in three or four ranks, depending on terrain, with the rear rank ready to deal with flank attacks. Hussars initially attacked in open order for ease of movement and maneuvering, but nearing impact with the enemy, they would squeeze together knee to knee, moving at full gallop. This difficult maneuver not only gave them powerful crushing strength, but also minimized losses from enemy firepower.

In comparison to the heavy cavalry of the West, which depended more on sheer weight than speed, the hussars could move quickly from standing to maximum speed. The deadly lance was practical only for the first few ranks, with the rest ready with their secondary weapon of preference, the war hammer, second only to the much-revered saber.

The hussars’ finest hour came on September 12, 1683, during the Turks’ second siege of Vienna. A combined army of Imperial Austro-German and Polish cavalry and infantry numbering 80,000 arrived—literally in the nick of time—led in person by the charismatic Jan Sobieski, the king of Poland. After an infantry battle lasting most of the day, Sobieski personally led 3,000 winged hussars in the largest cavalry charge in military history. Sobieski’s cavalry force of 20,000 cleaved the Turks out of their saddles, sending the highly touted spahis (light cavalry) into full retreat. The future rode with the hussars as well. Among Sobieski’s horsemen that day was a 19-year-old royal Savoyard, Prince Eugene. He survived, destined to become the greatest of Imperial generals and the man who stopped Turkish aggression against Europe once and for all in 1718. It is not known if Eugene carried a war hammer that day.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments