By Kelly Bell

The night of December 14, 1941, was bitterly cold in the North African desert. Midway between El Agheila and Tripoli, Libya, was the German and Italian air base outside the town of Tamet. Situated on the southern Mediterranean coast, it was a vital installation, supporting the Afrika Korps, commanded by General Erwin Rommel, and Field Marshal Albert Kesselring’s Panzer Army Afrika. Tamet was a plum target for Commonwealth forces.

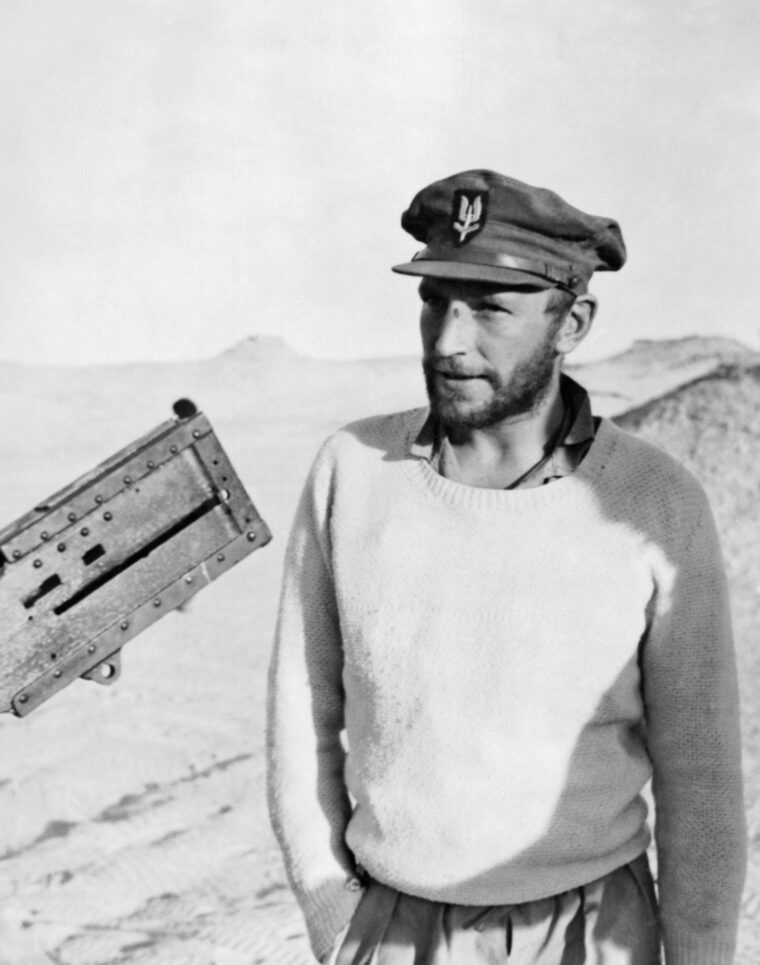

The base was shut down for the night. About 30 German and Italian airmen were eating, drinking, playing cards, and socializing in the wooden building that served as the officers’ mess. Preoccupied as they were, the pilots were flabbergasted when the door shattered under the impact of a booted foot. Filling the entrance was the silhouette of a huge man in British uniform with a submachine gun jammed against his right hip. As he opened fire, screams of terror and pain filled the room. By the time the Tommy gun’s drum of 50 rounds was empty, the room was splattered with blood and littered with dead and dying men. As suddenly as he had appeared, the massive enemy soldier was gone. He was Lieutenant Robert Blair “Paddy” Mayne of Britain’s Special Air Service (SAS), and he was far from finished with Tamet.

After Mayne and the five other members of his commando squad galloped into the stygian blackness of the surrounding desert, the base’s terrified, bewildered personnel spent almost an hour shooting at each other in the poor light. The initial attack had come at 2140 hours. Just after 2300, Mayne and his men crept back to the airfield and commenced planting explosives on the German and Italian aircraft parked around the base’s perimeter. They also booby trapped fuel and ammunition dumps and telephone poles. Just before midnight, Tamet erupted into volcanic fury as plastic explosives pulverized planes and ignited fuel and bombs. For the time being this pivotal Axis installation was utterly out of commission.

This first raid on Tamet was heralded a new style of warfare that would be a spear in the heart of Nazi Germany’s North African military presence. Paddy Mayne would be the executioner of this campaign, but only he knew how far he would carry the crusade. The Germans certainly did not anticipate the degree of devastation coming at them, and neither did the British. Mayne did not bother telling either side what he had in mind—he would show them.

Born in Newtownards, Ireland, on January 11, 1915, Mayne was already a member of the Queen’s University Officer Training Corps at the time of the 1938 Munich crisis. The following February he was commissioned into the 5th Light Anti-Artillery Territorial Regiment even though his superiors had evaluated him as “unruly and generally unreliable.” When war was declared in September, Mayne was left behind when his unit was sent to Egypt. The snub made an impression on the fearless and lethal but hard-drinking and undisciplined young soldier. When No. 11 Commando accepted him the following spring, he eagerly threw himself into the training regimen.

While Hitler’s armies overran continental Europe, Mayne was in Scotland enduring brutal physical training, becoming a weapons expert, learning map reading, swimming in full kit, rock climbing, practicing unarmed combat, using explosives, and learning how to organize transportation in all situations. Mayne was a deadly warrior by the time he was sent to the Mediterranean Theater in the summer of 1941.

Mayne’s unit participated in the abortive Litani River raid in Syria in which 120 Commonwealth soldiers were killed. After the survivors were sent to Cyprus for rest, Mayne became angry at his commanding officer, 24-year-old Lt. Col. Geoffrey Keyes, for not including him on the roster of a raid to abduct Rommel, which was never carried out. When Keyes imprudently approached Mayne in the mess hall one night, the resentful young Irishman rose from his chair and knocked his colonel senseless with a roundhouse right to the jaw. His next commanding officer, Colonel David Stirling, would be much wiser in utilizing Mayne’s deadly talents.

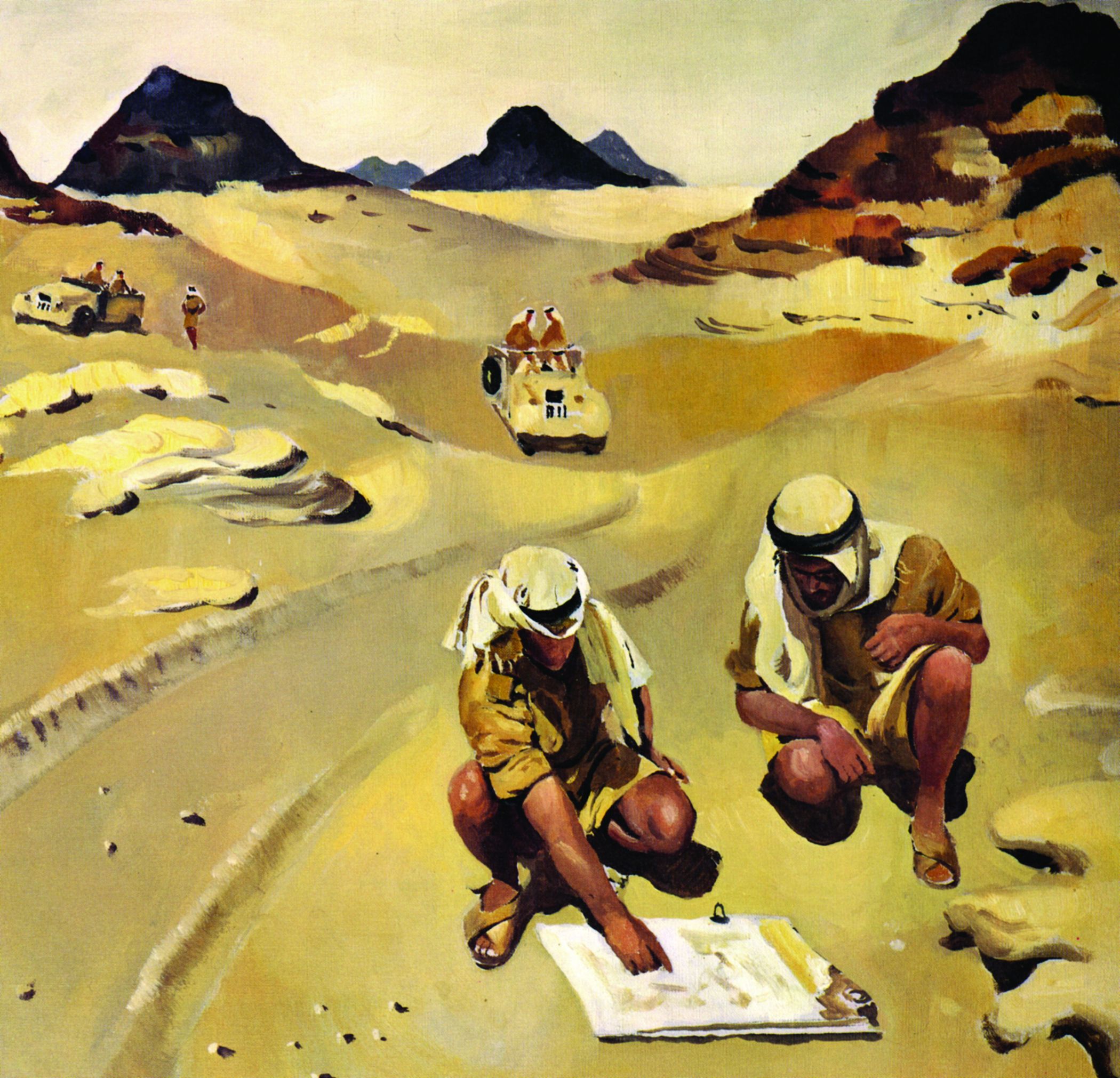

Hastily organizing the best available talent into the new SAS, Stirling relocated his unit to the North African mainland. Arranging to work in cooperation with the better publicized Long Range Desert Group (LRDG), Stirling and Mayne were ready for devastating special operations by late 1941. The inaugural raid on Tamet set the standard for ensuing SAS depredations. Realizing the Nazis and Fascists would not be expecting another raid on Tamet for a while after the destructive December 14 assault and would likely pack it with aircraft and supplies, the SAS returned to this mark on the 27th. The second visit resulted in 27 warplanes blown up along with several fuel dumps, three trucks, and two trailers crammed with vital spare parts for aircraft. Axis forces in the desert were already beginning to dread the night.

The sprawling Commonwealth land offensive of late 1941 had driven the Germans out of Benghazi, forcing them to ship supplies and reinforcements to the port of Bouerat, 350 miles to the west. A foray against Bouerat happened to fall at a time when the harbor was empty, and Mayne and his commandos found nothing to destroy but 18 fuel drums and a few food caches. The raiding party returned home in time for Rommel’s early 1942 counteroffensive that carried his forces all the way back to the Gazala Line, from which he had been driven two months earlier. In the midst of all this momentous military action, Mayne was awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

Rommel’s Offensive Resulted in Capturing 33,000 Prisoners, Including 5 Generals, and a Huge Haul of Tanks, Artillery, Food, and Medicine.

Now promoted to captain, he led his men in crucial attacks on Benghazi harbor and the adjacent airfields. On March 15, he set out to assail an airfield called Berka Satellite. Accompanied by two corporals named Rose and Bennett, and a Private Byrne, he reached the target at 3 am the next day. The commandos blew up the base’s fuel dumps, 15 aircraft, and a stack of 12 torpedoes. Escaping cleanly, they missed their rendezvous and had to walk 30 miles across the sweltering desert to the next LRDG pickup point.

On May 26, Rommel launched a pulverizing offensive, capturing the long-standing Allied bastion of Tobruk, bagging 33,000 prisoners, including five generals, and a huge haul of tanks, artillery pieces, food, and medicine. By the end of June, the British Eighth Army had been shoved all the way to El Alamein, across the Egyptian frontier, and was just 60 miles west of Alexandria.

After the aerial pounding he had inflicted on the British at Malta, Kesselring assumed the island was finished as a major threat and called off his warplanes. The Royal Air Force took full advantage of the respite and rushed large shipments of pilots and Supermarine Spitfire fighter planes to Malta. With the German supply lines being ravaged by warplanes, Luftwaffe units were forced to withdraw from the support of Rommel’s eastward advance and again target RAF airfields on the island. With Axis air power thus diluted, Mayne and Stirling realized their attacks on enemy airfields were imperative to further reducing Rommel’s priceless tactical air support.

The SAS swiftly outfitted a fleet of jeeps for mobile warfare. Welding two Vickers, rapid-firing machine guns facing forward on the vehicles and a swiveling .50-caliber Browning machine gun in the rear of each jeep, the commandos transformed the machines into devastating, high-speed gun platforms. By the end of July 1942 the unit was wholly motorized.

On July 4, even before the transformation was complete, an SAS convoy set out to raid the airfields scattered in the Bagush/Fuka region, 100 miles behind enemy lines. Reaching Bagush on the night of July 7, Mayne and three men blew up 22 aircraft with plastic explosives. This was far fewer than they had sabotaged, and Mayne growled, “Damn, we did 40 aircraft. Some of the bloody primers must have been damp.” Not about to leave the job undone, Mayne and Stirling charged their vehicles onto the airfield and opened up with their Vickers guns, firing 1,200 rounds per minute apiece. Stunned by this new assault after they assumed the saboteurs had departed, the Germans ran for cover as the raiders shot to pieces 12 more of the Luftwaffe’s precious warplanes.

The largely overlooked effectiveness of the SAS is demonstrated by comparing this night’s work with one of the RAF’s greatest victories during the Battle of Britain. On September 18, 1940, England’s renowned legless Wing Commander Douglas Bader and his squadrons had garnered international headlines by downing 30 German planes. Mayne and his marauders destroyed 34 on the night of July 7, 1942, contributing mightily to the Eighth Army’s victory at El Alamein in October. Yet, outside the immediate area, no one took note.

The clinical detachment and unselfishness with which Mayne approached his duty is typified by his encounter with a superior, Maj. Gen. David Lloyd Owen, after a raid on the German airfield at Fuka. “How were things tonight?” asked Owen. “A bit trickier tonight,” replied Mayne. “They had posted a sentry on nearly every bloody plane. I had to knife the sentries before I could place the bombs.” When Owen asked how many of these guards Mayne had killed that night, the casual reply was, “Seventeen.” Far from demanding recognition and reward for this mass throat cutting, he never mentioned it again. Had Owen not asked, the incident would have been recorded as just another night’s work for the SAS. It is possible nobody but Mayne would have ever known about it.

In early July, Mayne and Stirling contrived a plan for a major motorized raid on the sprawling Luftwaffe base at El Daba, about 50 miles west of El Alamein. By this time, the Germans had significantly strengthened security around their bases. The large number of sentries Mayne had been forced to slay at Fuka was evidence of this. The two commanders therefore conspired to launch a sudden jeep-borne attack out of the darkness, plowing through perimeter defenses and shooting up the installations from within.

On the night of July 9, Mayne used this strategy on El Daba and destroyed 14 aircraft. Two nights later he led his jeeps back to Fuka and shot to pieces 22 more planes. This ongoing attrition of German airpower profoundly affected Axis morale as the Third Reich could not protect its most important North African military installations when they were hundreds of miles from the front lines. Mayne and his SAS men, even though they were among the most effective military units then fighting, remained virtually unknown.

At this point Allied reconnaissance flights revealed that Sidi Haneish, another Luftwaffe field in the Fuka area, was not only one of Rommel’s main aircraft assembly areas, but that it was packed with his priceless Junkers Ju-52 transport planes. Already in short supply, these tri-motor cargo carriers were invaluable for making his eastward advance possible by ferrying in men, medicine, munitions, and provisions. Mayne and Stirling devised a plot to send 18 jeeps against the facility under a full moon. Because the bright moonlight would make it difficult for the SAS to approach the field unnoticed, the Germans would not be expecting a raid.

The Jeeps Continued Advancing and Barged Straight into the Base as Their Gunners Opened up with Scores of Twin Vickers in a Pulverizing Display of Firepower.

The vehicles would brazenly advance in line abreast, and as they neared their target’s perimeter they would form into two columns, plunge into the base at high speed, and shoot. With the jeeps spaced just five yards apart and so many powerful, fast-firing guns blazing at once, perfect timing was crucial to avoiding the raiders’ hitting each other with their gunfire or colliding. After exhaustively rehearsing the assault, Mayne led the strike force into the Sahara at dusk on July 27.

Four hours later, the raiders were within a half mile of the airfield and preparing to form into their twin attack columns when the installation ahead was suddenly flooded with light. At first, the raiders thought they had been spotted, but it turned out that the brilliant illumination was guiding a Heinkel He-111 bomber returning from a night patrol. The jeeps continued advancing and barged straight into the base as their gunners opened up with scores of twin Vickers in a pulverizing display of firepower.

The Ju-52s were there all right, but the base turned out to be even more of a prime target than Mayne and Stirling had expected as they wound their vehicles between rows of parked Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters, Heinkels, and Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive-bombers. The Germans were completely surprised. Within minutes the base was ablaze, but Mayne would not leave any job unfinished. As the attackers were leaving, he spied a lone Ju-52 that the raiders had overlooked. With his machine guns out of ammunition, Mayne jumped from his jeep, ran up to the plane, slapped a plastic bomb onto its wing, galloped back to his vehicle, and roared off into the desert.

In this attack the SAS lost one man and one jeep in exchange for at least 40 Luftwaffe aircraft destroyed. This spectacular success in a long line of devastating actions led Eighth Army high command in Cairo to decide Mayne and his destructive little outfit should now be used in a large-scale operation.

General Bernard Law Montgomery, the newly appointed commander of the Eighth Army, was anxious to achieve a decisive, exclusively Commonwealth, military victory before the United States entered the war in force. He decided the SAS would take part in a large-scale operation against Benghazi Harbor. Mayne would have to absorb 100 new recruits in order to bring the unit up to the strength of 220 men required for the mission. There was insufficient time for him to train this influx of newcomers to his exacting standards. Forced to adhere to a rigid timetable, the unit would lose its valuable asset of flexibility, and being part of a large force would mean loss of the crucial SAS element of surprise. Still, Mayne readied his troops as best he could.

The first leg of the expedition was an 800-mile drive to the mission’s staging point at Kufra Oasis. From there the convoy had another 600 miles to travel to the mountainous Djebel region to assemble for the assault on Benghazi, 20 miles away. Although high command in Cairo had received repeated intelligence reports that the enemy was aware of the approaching strike force, Mayne and Stirling were ordered to go ahead with the attack. On the night of September 13, the raiders set out for Benghazi.

Stopping at an unmanned roadblock just outside the city, the convoy was ambushed from both sides of the road. Sent reeling back to Kufra, the column still had another 800 miles to go to reach friendly lines. Constantly strafed by the vengeful Luftwaffe, the force lost men and machines steadily along the route. At one point Mayne was wildly maneuvering his jeep while being strafed by a relentless German pilot. When one of the men in the jeep was wounded and fell from the vehicle, Mayne kept going until the airman finally broke off his attack. After finding cover and parking his jeep, Mayne, not knowing whether the man who had fallen from the vehicle was dead or alive, backtracked until he found the wounded soldier and carried him on his shoulders back to the jeep.

The Benghazi fiasco cost 50 men and 50 vehicles and justified Mayne’s misgivings about integrating the SAS into a large-scale offensive. Such a move wasted their unique talents and commando training. Montgomery seemed to realize this and permitted Stirling and Mayne to return to their covert ways.

In late October, the unit had set up a new base of operations inside the Sand Sea. The facility was about 200 miles behind enemy lines around El Alamein and 150 miles south of the coastal road and railway Rommel was using as supply routes. The site was well placed for attacks on both supply convoys and forward air bases. Remote as it was, few German aircraft were in the area.

Soon after settling into this new location, recently arrived SAS 2nd Lt. Johnny Wiseman had his “first terrifying experience” with Paddy Mayne. After having “a lot of rum” Mayne decided Wiseman would look good with half a beard, so he knocked the junior officer to the floor, pinned him down, and shouted, “Get me my throat-cut!” Decades later Wiseman recounted how his inebriated commanding officer “took off half my beard without any water, without anything. There was this enormous man sitting on top of me. I’ve never been so frightened in my life. I was sure he was about to cut my throat. After that nothing in the war ever frightened me! That cured me.”

The SAS was closely involved in Montgomery’s offensive in the autumn of 1942. With Rommel dug in at El Agheila, Mayne and 90 of his men were ordered to relocate to a wadi called Bir Zalten, about 100 miles south of Rommel’s lines. With 30 jeeps, the SAS was tasked with haunting the 400 miles of highway linking the Germans with their supply base at Tripoli. Axis forces would be compelled to run the gauntlet of jeep-borne raiders at night and expose their convoys to incessant strafing by the RAF during daylight hours. Montgomery personally approved the plan. He was quoted as saying the SAS “could have a decisive effect, yes, a really decisive effect, on my forthcoming offensive.”

“These British Saboteurs and Their Accomplices are to be Hunted Down and Exterminated Without Mercy.”

Averaging 16 raids per week, the jeep commandos made nocturnal supply runs at least as perilous for the Afrika Korps as daylight runs under a sky controlled by the Royal Air Force. The pinch on the Germans’ supplies became so severe that Rommel detailed some of his armored patrols to fruitlessly chase the night raiders. On October 8, 1942, Hitler himself issued a formal order that “these British saboteurs and their accomplices are to be hunted down and exterminated without mercy.”

With the flow of men, weapons, ammunition, food, medicine, and even mail cut to a trickle, Rommel’s forces had no chance when Montgomery’s massive, copiously supplied army fell upon them at El Alamein. Montgomery achieved his coveted goal of a decisive Commonwealth victory before the Americans dominated the Allied war effort. The Germans retreated westward.

During Operation Torch in November, U.S. troops landed along the western coast of North Africa, threatening to squeeze the Axis forces in a vise. By the end of January, the Allies had captured Tripoli. Weeks later, the battle for North Africa was over.

Stirling was captured before the final German surrender in North Africa, and Mayne was promoted to lieutenant colonel and given command of the SAS. His first task was to convince his superiors not to disband his outfit. Captain Derrick Harrison later recalled, “Paddy fought desperately to keep us alive. He managed to do it by changing our role. We became Special Raiding Squadron, SAS.”

Miffed at having to politic desperately to preserve the mere existence of such a heroic outfit, and still angry over the Army’s recent refusal to allow him to return to Ireland for his father’s funeral, Mayne went on a drunken rampage while on leave in Cairo. Owen was present at this brouhaha and later said, “I was there. I saw Paddy throw the provost-marshal and two military policemen down the steps of Shepherd’s Hotel.” Although Mayne was arrested for this escapade, his superiors were aware of his value as a soldier and made certain he was not court-martialed. He was instead sent off to prepare the newly named Special Raiding Squadron for the invasion of Sicily.

Mayne threw himself into retraining his troops for non-desert warfare, even teaching them to fight on horseback. However, the SAS would never again reach the heights of gallantry, effectiveness, and adventure it had achieved in North Africa. Now called the SRS, the unit fought through Sicily, Italy, France, and into Germany. During the Normandy campaign the unit worked in cooperation with the French Maquis, operating destructively behind German lines and easing the advance of the invading Allies. Mayne continued his occasional drunken carousing, at one point riding in the back of one of his jeeps through the streets of newly secured Le Mans, France, firing his .50-caliber guns into the air. Arrested by military police and brought before General George S. Patton, Jr., commander of the U.S. Third Army, he shamed Patton into releasing him by slurring, “I hope I didn’t frighten your men.”

The final days of the war in Europe saw some bloody combat for the SRS. On April 9, 1945, Lt. Col. Mayne and his men were leading a regiment of the Canadian 4th Armored Division through the German countryside northeast of the city of Oldenburg, en route to Kiel, when the column was ambushed by German troops firing from a house to the side of the road.

Grabbing a machine gun, Mayne ran into the house alone and gunned down every enemy soldier inside. He then ran back outside, deployed his men, and jumped behind the wheel of a jeep. With another officer as gunner, Mayne drove about 100 yards farther up the road to where the enemy was raking the convoy with gunfire from positions in a wooded area. Fully exposed to the Germans, Mayne drove his jeep slowly up and down the thoroughfare while his gunner fired at the enemy positions. Although still under fire, he then returned his vehicle to the point of ambush and lifted numerous wounded British and Canadian soldiers out of the roadway, placed them in his jeep, and drove them to the rear.

The column, which had been at a standstill until Mayne’s appearance at the point, then continued its advance until it was a full 20 miles ahead of the division’s main body. With their rear threatened by the appearance of Mayne and his spearhead, the Germans withdrew, easing the advance of the rest of the division. Mayne both saved the wounded and routed the enemy, and never mentioned the incident again.

The encounter at Oldenburg earned Mayne his third bar to the Distinguished Service Order. However, in 2005, the House of Commons in London voted in favor of upgrading the DSO to the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest decoration for valor.

In the spring of 1945, the SRS helped wrap up the war in Europe by working closely with the Canadian 4th Armored Division. Mayne and his soldiers chewed holes in German defensive lines so that the Canadian tank columns could penetrate. War’s end saw the SRS participating in securing the Baltic port of Kiel.

Mayne’s unselfish dedication to his cause is exemplified by how he kept secret a painful back injury he had suffered in North Africa. His repeated parachute drops into France in 1944 agonizingly exacerbated the damaged vertebra, but he kept it a closely guarded secret. No one else knew about the injury until after the war. He did not let his back trouble stop him from earning the Distinguished Service Order with three bars, a testament to his displays of incredible heroism on four separate occasions. Mayne was one of the most highly decorated soldiers of World War II.

After being mustered out of the service he spent the next 10 years wandering aimlessly from one job to another. Lost in peacetime, this massive soldier’s drinking grew worse. During the predawn hours of December 15, 1955, after having too many drinks, 40-year-old Mayne was killed in a car crash in his hometown of Newtownards.

After easily surviving everything the Third Reich could throw at him for four years, Blair Mayne fell prey to the peace he had done so much to achieve. Never married and childless, his only legacy is his fantastic military record. With no room in his own soul for conceit, he and his valor were largely lost among the enormous egos of the Allied war heroes he supported. He made their jobs much easier.

Kelly Bell writes regularly on various aspects of World War II, including the naval war in the Pacific and the land war in Western Europe. He resides in Tyler, Texas.

What a great story. What a great man. What a great hero.

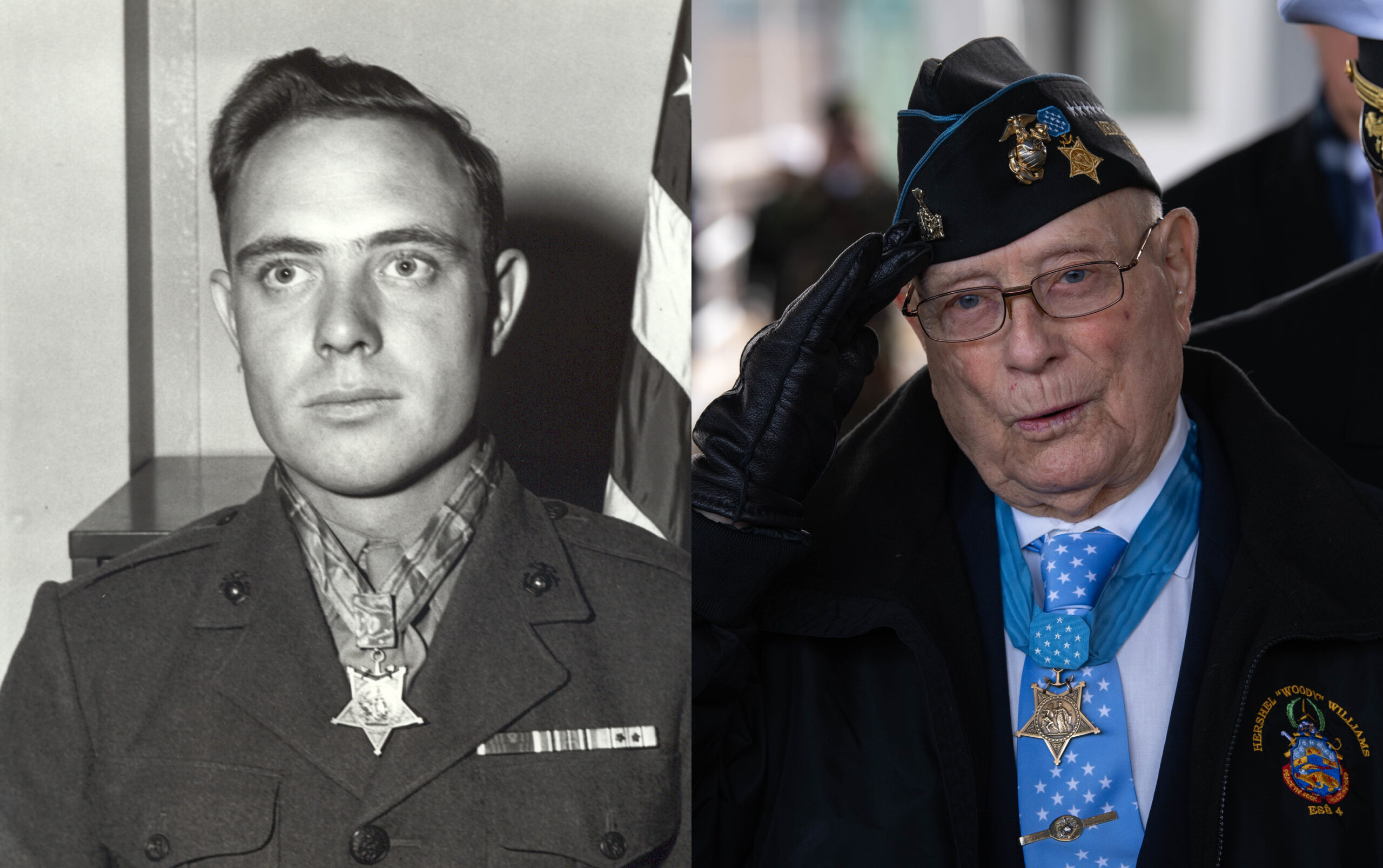

The U S Army had Audie Murphy, who won the Medal of Honor twice. He starred in his own bio-pic, but had a shorter than usual life. Paddy Mayne, on the other hand, did multiples of what Murphy did, but so secretly it took 60 years after war’s end to upgrade one of his medals to the British version. Or perhaps Murphy earned two of the US’s version of the Victoria Cross.

Comparisons are often odious; both men rode with blazing weapons into direct fire and came out unscathed. But Mayne is hands-down the brighter of these two stars.

Yeah, but Audi Murphy was a foot shorter

No one ‘wins’ a Medal of Honor, it’s not a contest.

When does the movie come out ? What a great movie about his life that would be !

There should be a movie about his war heroics….

Was there not a TV series called the Desert Rats about these heroic men?

It was called the Rat Patrol.

It is my understanding that the Long Range Desert Group was essentially a kiwi outfit. Either way, it seems that the Irish propensity for a drink and a fight did wonders for taking the fight up to the enemy. The SAS’s descendant outfit , here in Oz, has a similar reputation for being a bit unconventional but ruthlessly effective.

General Wavell wanted Kiwis. They were good. Paddy was also good, as were many other brave young men. Where would we have been without them I ask?

Two others we hear little about. Gen Charles Orde-Wingate and Brig Mike Calvert both od the Chindits.

Dear world out there……… would you believe it that there were also Rhodesians and South Africans in the LRDG……… not just aus’ and kiwi- texans.

Such is that. I knew personally some members of the LRDG- SAS first command……..But, the world is against the Rhodesians and SA’s who gave their lives for the worlds freedom.