By Roy Morris Jr.

John Pope’s second campaign as an army commander went considerably better than his first. Not that it did his reputation—or Abraham Lincoln’s, for that matter—any particular good. Following his disastrous performance at Second Manassas, the Federal government shipped Pope about as far away as it was possible to ship a serving general—Minnesota. In that sparsely settled state, Union-loving men had flocked to the cause, creating a drain on available manpower that would have unexpected and tragic consequences for the families and friends they left behind.

Disgruntled by years of neglect by the government, particularly their underhanded treatment by Indian post traders, the Santee Sioux seized the opportunity left by the volunteers’ departure to stage a brief but furious rebellion in the summer of 1862. Near starvation after traders refused them food because the Civil War-preoccupied Congress had delayed its annual appropriation of annuities, the Sioux rose spontaneously after trader Andrew J. Myrick turned them away with a dismissive shrug: “If they are hungry, let them eat grass.”

The Sioux Rebellion at Acton

At almost exactly the same time that Pope was leading the Union Army of Virginia to defeat at Manassas, the Sioux launched their rebellion by murdering five white settlers (including two women) at Acton, Minnesota. Tribal leaders urged Chief Little Crow to lead a war against the whites. At first, Little Crow demurred. “The white men are like locust,” he warned. “They fly so thick that the whole sky is a snowstorm. You may kill one, two, ten, yes, as many as the leaves in the forest yonder, and their brothers will not miss them. Kill one, two, ten, and ten times ten will come to kill you.” Reluctantly, Little Crow agreed to lead the Sioux into battle. On the morning of August 18, the Indians attacked the Lower Sioux Agency and killed 13 whites, including trader Myrick, whose corpse was found with blood-stained grass stuffed into its mouth. The Sioux burned and looted the agency.

A National War

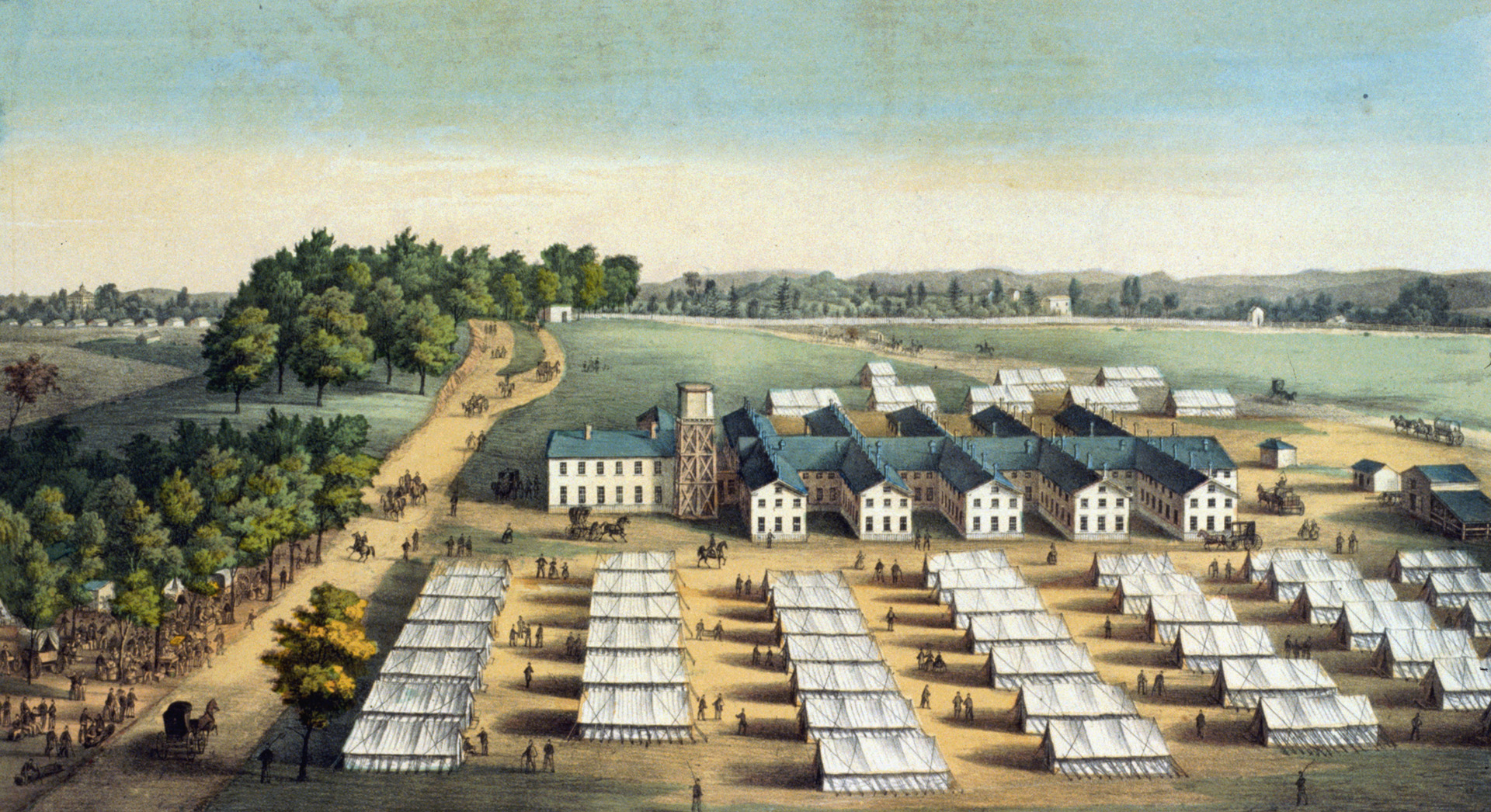

As Indian raids continued in the surrounding countryside, white refugees dashed for the safety of Fort Ridgely. Meanwhile, Governor Andrew Ramsey urgently requested reinforcements from Washington. “This is not our war; it is a national war,” he telegraphed Lincoln. “More than 500 whites have been murdered by Indians.” The Sioux continued their rampage through 20 Minnesota counties, killing some 800 settlers and carrying off untold numbers of women and children. There were widespread reports of torture, mutilation and rape. Lincoln responded by naming Pope the commander of a newly created Military Department of the Northwest, with orders to end the bloodshed in Minnesota. Pope, in turn, directed Colonel Henry H. Sibley to put down the rebellion. “It is my purpose utterly to exterminate the Sioux if I have the power to do so,” said Pope, less than chastened after his recent thrashing by Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. “They are to be treated as maniacs or wild beasts.” With the help of the newly arrived 3rd Minnesota Regiment, which had been captured and paroled by the Confederates at Murfreesboro, Sibley attacked the Sioux at Wood Lake. After two hours of fierce fighting, the Indians dispersed westward into the open prairies. A government commission was empaneled to try the ring leaders of the uprising, and 303 Sioux were condemned to death, often on flimsy or nonexistent evidence. Public outcry forced Lincoln to intercede and pare down the list to 38. The largest mass hanging in American history took place on the day after Christmas, 1862. Lincoln actually lost public support in Minnesota after the executions. When Ramsey complained that Lincoln would have preserved his popularity by hanging more Indians, the president responded dryly: “I could not afford to hang men for votes.”

Why didn’t you describe the military actions of this conflict? Redwood Ferry, Fort Abercrombie, Birch Coulee, the siege of New Ulm, the two battles at Fort Ridgely? And afterwards many Dakota were banished from the state and sent to the Dakotas and Nebraska resulting in many deaths due to disease and starvation. The story seems rather incomplete.

mainThis article is a sidebar to the main story (both from Military Heritage magazine). Here’s the main article:

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/2016/09/29/dakota-war-of-1862-what-caused-the-great-sioux-uprising/