By Michael D. Hull

A variety of outstanding weapons and pieces of equipment affected the course of World War II for both the Allies and the Axis powers.

There was the British workhorse 25-pounder field gun, the deadly Supermarine Spitfire fighter, the Avro Lancaster bomber, the universal carrier, and the dependable Bren light machine gun; the rugged Soviet T-34, regarded as the best tank of the war; the devastating German 88mm antiaircraft and artillery gun, and the formidable Tiger tank series; the feared Japanese Mitsubishi Zero carrier fighter; and, from the American “arsenal of democracy” came the ubiquitous jeep, the Sherman medium tank, the half-track, the bazooka rocket launcher, the universally used C-47 transport plane—and the Garand M-1 infantry rifle.

“The Greatest Battle Implement Ever Devised”

Designed long before the war by John C. Garand, a French Canadian engineer, the semiautomatic, gas-operated, air-cooled, clip-fed M-1 was the main infantry weapon of the U.S. Army in 1941-1945. Firing a .30-caliber cartridge in eight-round clips, it was the world’s first semiautomatic rifle in military service and was used wherever American soldiers saw action, in North Africa, Sicily, Italy, the Pacific Theater, France, Belgium, Holland, and Germany.

The M-1 had a significant advantage over the bolt-action rifles used by the other Allied and enemy armies because of its semiautomatic mechanism. Its shooter could fire as fast as he could squeeze the trigger. A trained soldier was able to fire eight rounds within 20 seconds and then quickly insert a full clip without taking his sights off the target. He could also load with regular ball, tracer, armor-piercing, or incendiary ammunition, and with relative ease he could turn the weapon into a grenade launcher.

Although it weighed a hefty nine and a half pounds, John C. Garand’s rifle was easy to maintain and was deadly accurate to a range of about 550 yards. Despite its weight, GIs loved the M-1. “I dropped five Krauts with my M-1,” said one soldier in the European Theater. From the Pacific Theater came another report: “As eight Japs came charging at him with fixed bayonets, the American Marine dropped all of them with his trusty M-1 Garand. The loud ‘pling’ [of the ejecting clip] was heard by his comrades as the last Jap fell to the ground.”

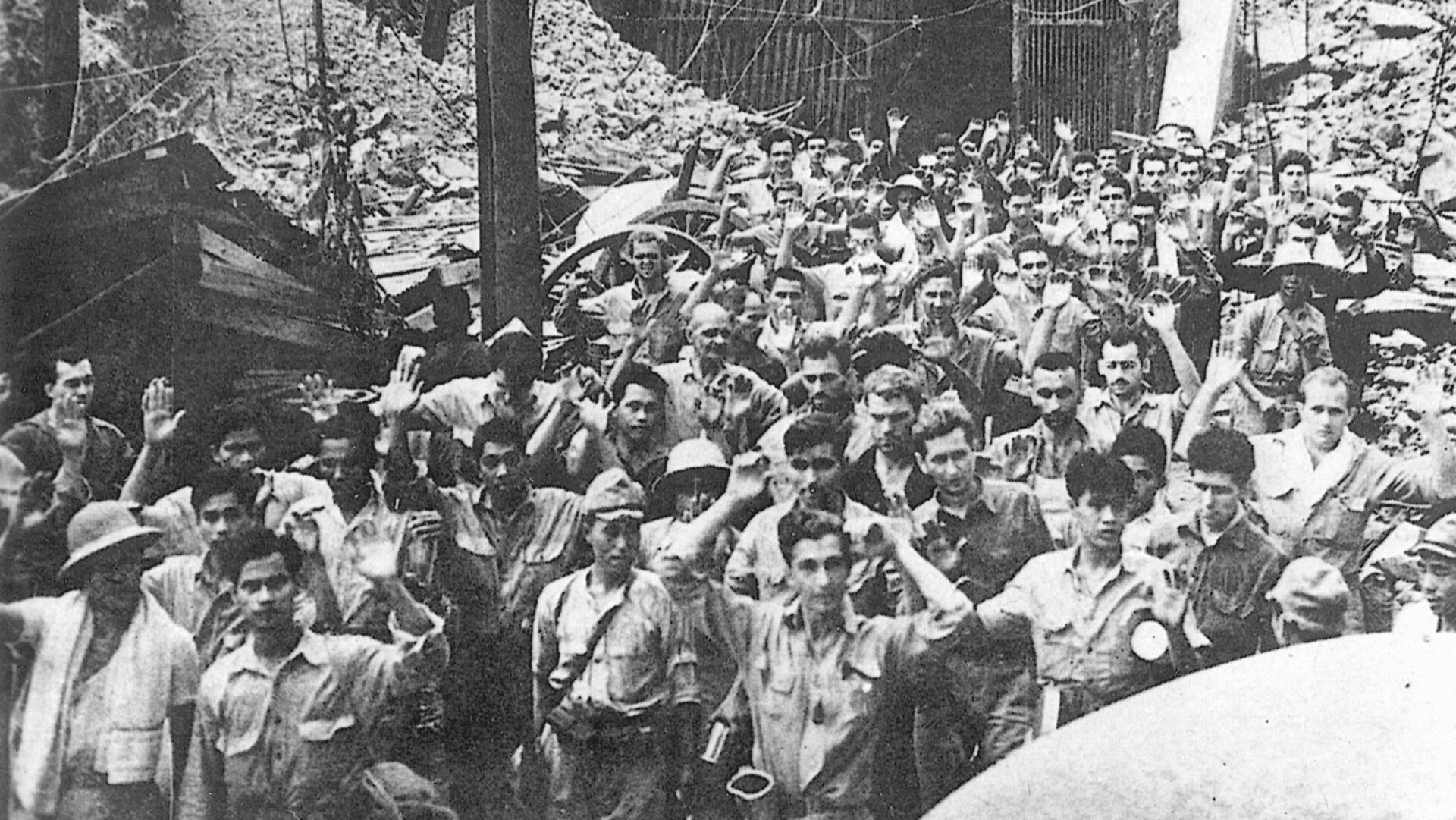

Armed with the Garand, one or two U.S. soldiers could kill an entire enemy squad before it reached its objective. In short-range jungle fighting in the Far East, where opposing forces sometimes met each other in column formation on a narrow path, the penetration of the rifle’s powerful .30-06 cartridge enabled a single GI or Marine to kill up to three Japanese soldiers with a single round.

The rifle’s accuracy and durability earned high praise from generals as well as GIs. During the bitter, doomed struggle on Bataan in early 1942, General Douglas A. MacArthur, later commander of Allied ground forces in the Pacific Theater, reported on the M-1 to the U.S. Ordnance Department: “Under combat conditions, it operated with no mechanical defects, and when used in foxholes did not develop stoppages from dust or dirt. It has been in almost constant action for as much as a week without cleaning or lubrication.”

Lieutenant General George S. Patton, Jr., commander of the highballing Third Army in Europe in 1944-1945, reported to the Ordnance Department on January 26, 1945: “In my opinion, the M-1 rifle is the greatest battle implement ever devised.”

The M-1 was not as elegant as the Army’s beloved Springfield M1903 rifle, which it replaced, but it was more rugged, better suited to mass production, three times faster in rate of fire, only slightly less accurate, and much easier for a recruit to learn to handle.

The Man Behind the Marvel

The M-1’s inventor, John Cantius Garand, was born on January 1, 1888, on a small farm in the town of Saint Remi, 17 miles south of Montreal, Quebec. At the age of 11, he moved with his family to rural Connecticut. John attended school until the age of 12 and then started work, sweeping floors in a textile mill. An inquisitive boy, he became fascinated by the machinery around him and was soon using his spare time to learn about mechanics. By the age of 18, he was employed as a machinist.

John became a tool and gauge maker, took correspondence courses, and went to work at the Brown & Sharpe tool factory in Providence, Rhode Island. As a young apprentice machine-tool designer there, he found himself caught up in a revolution in machine-tool design. The growing automobile industry was demanding precision-machined components at an unprecedented cost and level of production, so the machine-tool industry had to reinvent itself.

John learned much at Brown & Sharpe, particularly the integration of design with production machinery, and his experience there would never be far from his mind. After he worked for a time in a shooting gallery, John Garand became fond of guns and target shooting. He started designing guns as a hobby. After reading about the U.S. Army’s mechanical problems with weapons during the World War I era, John designed a light machine gun. The Army took bids on designs, and John’s blueprint was eventually selected by the War Department.

He was given a position at the U.S. Bureau of Standards in August 1918 and the task of perfecting his weapon. Garand finished work on his prototype within 18 months, but World War I had ended by then and the Army lost interest. Nevertheless, the hard-working young inventor was kept on as a consulting engineer. He was now known in the gun-making world.

At the Springfield Armory

In November 1919, Garand was assigned to the historic U.S. Armory in the western Massachusetts city of Springfield. Established in 1777 by General George Washington and his artillery chief, Colonel Henry Knox, the armory was used to store muskets, cannons, and other arms during the American Revolution. Later, cartridges, gun carriages, and 800,000 muskets were produced there. With the destruction of the Harpers Ferry Armory and Arsenal during the Civil War, the Springfield Armory became the main federal manufacturing center for small arms. It was immortalized in the poem, “The Arsenal at Springfield,” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

At Springfield, John Garand was to spend the rest of his career, become the chief ordnance officer, and make a unique contribution to American infantry firepower in World War II. When asked to design a semiautomatic infantry rifle for the Army, he drew on his Brown & Sharpe experience. Such a weapon would require precision in machining and assembly, with a design incorporating functionality and predictability. But things would have to be changed at the Springfield Armory if it was to mass produce a top-quality infantry weapon.

Garand learned that the armory, which had given its name to the legendary Springfield rifle series, had failed to turn out even a fraction of the weapons needed by the Army in World War I, and many of those it did produce were soon scrapped. The Springfield Armory manufactured more than 265,000 Springfield M1903 rifles during the war, but this was insufficient for the rapidly expanding Army’s needs. So, an additional 47,251 were turned out by the Rock Island (Ill.) Arsenal. The war proved to be a blow to the Springfield Armory’s prestige from which it never fully recovered, although it had warned the War Department for several years that its production capabilities were obsolete and unsuited for modern firearms.

Designing a New Rifle

When he started work at Springfield, the bespectacled, studious Garand found himself having to upgrade its production facilities. He concluded that the armory was producing the wrong rifle. The bolt-action Springfield M1903 was a fine infantry rifle, but it was difficult to produce using modern machine tools. It was designed to be constructed by skilled armorers at a leisurely pace and with abundant labor. Garand realized that time and skilled manpower were always in short supply in time of war, so he believed that the only logical course was to abandon the M1903 and start anew. The design of the British M1917 Enfield rifle produced during World War I had had the advantage of being built with machine tools and unskilled labor.

In 1919, Garand started design sketches on a new rifle. He became a U.S. citizen in 1920 and qualified for civil service with an annual salary of $3,500. He thus forfeited any chance of profits he would have gained as a private inventor. He trod a long, hard road toward the creation of an acceptable modern infantry rifle. His main problem was the Army Ordnance Committee, which demanded a rifle design suited to infantrymen, cavalrymen, and tank crews alike. Announcing its criteria for a new infantry rifle in 1926, the Army wanted it to use as many parts as possible from the old M1903 and to fire the standard .30-06 cartridge, millions of rounds of which were still stockpiled. So, at a time when Congress was paring the nation’s military budget to minimum levels, General MacArthur, then Army chief of staff, ordered the production of a rifle chambered for the war surplus .30-caliber ammunition.

Garand spent long hours, year after year, through the 1920s and early 1930s, designing a rifle that would meet Army specifications. Doing much work in his spare time over the next 15 years, he produced preliminary designs, detail work, and further designs. While toiling in the Springfield Armory’s experimental shop, he planned new buildings and the machinery required to turn out his weapon. Eventually, the armory’s Water Shops facility became one of the most advanced metalworking plants in the world.

John Garand refined prototypes of his rifle in the late 1920s and early 1930s, and it was finally patented in his name in 1934. Although officially adopted in 1932 by the Army after grueling tests as the standard infantry rifle, it did not formally enter service and replace the Springfield M1903 until 1936 after an executive decision by General MacArthur. Garand’s rifle could fire more than twice as fast as its predecessor. Production started in 1937.

Proven on the Field

The first production model of the Garand M-1 rifle was successfully proof-fired, function-fired, and fired for accuracy on July 17, 1937. Production got off to a slow start, and only a small number were available in 1939. By the time the United States entered World War II the day after the Pearl Harbor attack in December 1941, M-1 rifles were still in short supply. Most Army and Marine Corps units were still equipped with Springfields.

But mass production soon got under way and was expanded on the weapon that would revolutionize U.S. infantry firepower. By the end of the war in 1945, the Springfield Armory had produced 4.5 million M-1s, with another million turned out by three arms contractors.

Many firearms experts in the 1930s had doubted the accuracy and reliability of the semiautomatic Garand rifle, but they would be proved wrong on both counts. Compared with its bolt-action counterparts of the World War II era (the trusty British Lee-Enfield .303 infantry rifle, the long-serving Russian-Belgian Mosin-Nagant, and the Springfield), Garand’s weapon represented a major advance in combat rifle design. The Enfield and the German Mauser had better workmanship, but the M-1 fired faster, just as accurately, and could be easily maintained under virtually any battlefield situation. It took rough handling and still fired, and it could be field stripped in a matter of seconds.

M-1 rifles were to prove their effectiveness and reliability in the desert wastes of Tunisia and Morocco, the winter mud of Italy, the fog-shrouded Aleutian Islands, the steaming swamps and jungles of Guadalcanal and New Guinea, the baked coral of Tarawa and Okinawa, and the snow and ice of the Ardennes Forest. Contemporary semiautomatic rifles such as the German Gewehr 43 and the Russian Tokarev SVT-40 failed to measure up to the M-1’s toughness and ease of use. The Japanese developed a prototype semiautomatic rifle, but it never reached the production stage. The British Army tested the Garand M-1 as a possible replacement for its Lee-Enfield No. 1 Mark III weapon but rejected it after a series of tests under simulated combat conditions.

The M-1 became an indispensable part of the American small-arms arsenal for more than two decades, seeing action in all theaters of operation, in all types of terrain and extremes of weather, and in every campaign and battle, large and small, fought by U.S. soldiers and Marines. Military commanders praised Garand’s weapon, and it was acknowledged as giving the U.S. infantry a great advantage over its foes. It was used later in the 1950-1953 Korean War and in the early days of the Vietnam War. As one World War II infantry sergeant told his son, “That’s a man’s gun.”

Building the Guns

The Springfield Armory produced modest quantities of the Garand rifle in the late 1930s and ever-increasing quantities from 1940 to late 1945. Like many Allied war production plants during World War II, the Springfield Armory tapped a rich labor source—women. Up to 70 percent of its labor force was female, with many of the WOWs (women ordnance workers) painstakingly forging the weapon that would be used by their husbands, fathers, sons, brothers, and sweethearts in uniform. The armory also employed a significant number of African Americans.

After the outbreak of the war in Europe at the beginning of September 1939, Winchester Repeating Arms Co. of New Haven, Connecticut, was awarded a contract to turn out M-1 rifles. Winchester deliveries were started in 1941 and ended in 1945.

Stunning Impact on the Battlefield

Although soldiers groused and kidded about the weight of the M-1, Garand’s weapon gave stout service wherever it was carried. Often making the difference between life and death for the men on the front lines, it played a vital tactical role and, ultimately, a decisive role in the Allied victory over the forces of Nazi Germany, Italy, and Japan. The impact of the M-1 on the battlefield stimulated both Allied and enemy forces to augment the issue of semiautomatic and fully automatic weapons then in production, as well as to develop new types of infantry firearms. The M-1 proved to be both a milestone in the development of small arms and a crucial element in the U.S. arsenal.

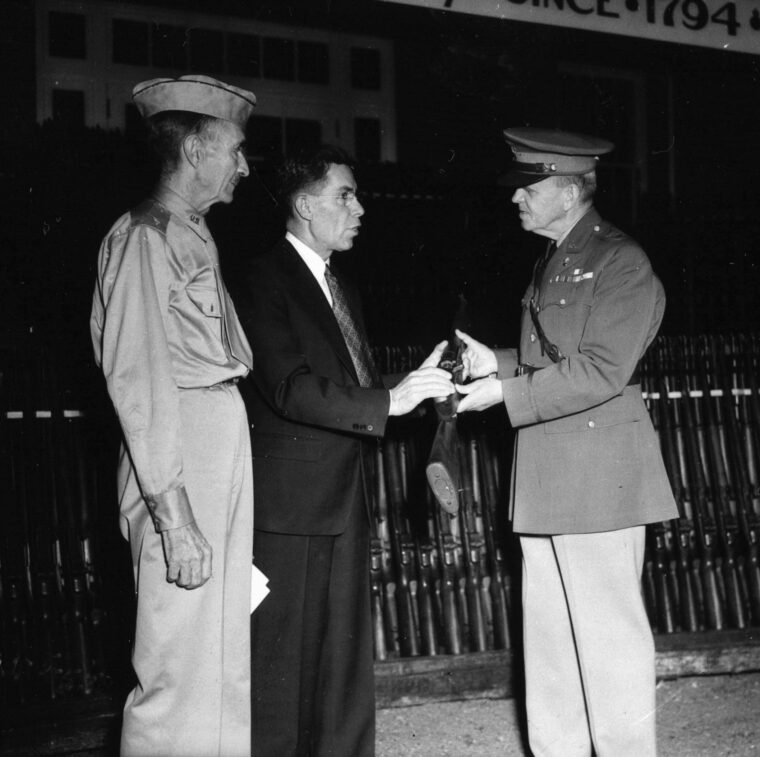

For his unstinting work at the Springfield Armory, Garand was awarded the Medal for Meritorious Service in 1941 and the Medal for Merit in 1944. He received no royalties or any other monetary compensation beyond his modest civil service salary, and he freely assigned all of his patents to the government. A bill was introduced in Congress to award him $100,000 in appreciation of his efforts, but it failed to pass.

Retiring the M-1 Garand

Much of the M-1 inventory underwent repair or rebuilding at the end of World War II. After U.S. forces became engaged in the Korean War, the Defense Department decided that more Garand rifles were needed, so contracts were awarded to the International Harvester plant in Evansville, Indiana, and to Harrington & Richardson Arms Co. in Worcester, Massachusetts. They produced 500,000 M-1s during 1953-1956. A number of NATO countries adopted the M-1 after 1948, and a further 100,000 Garand rifles were turned out in Italy by the Beretta gun company, using Winchester Repeating Arms Co. tooling.

The Marine Corps in 1951 adopted a variant of the rifle, the M1C with telescopic sight, as its official sniper rifle, and the Navy also used the Garand rechambered for a 7.62mm NATO round. The M-1 remained in U.S. Army service until 1957, when it was replaced by the lighter, fully automatic M-14 rifle. A fully loaded 20-round magazine made the M-14’s weight similar to that of a loaded M-1.

“Yes, the Garand was heavier,” said veteran Hopkins, “but, as a number of World War II and Korean War veterans told me, in the chaos of close combat in desperate circumstances, it makes a ‘hell of an effective club.’ You certainly can’t say the same for the M-16 of today, whatever its virtues. Personally, I never heard any complaints about the M-1’s weight, and still believe it was the greatest infantry weapon ever devised for its time.”

Several years after it went out of production, the Garand rifle remained in service with the U.S. National Guard and in the armies of many other countries, including Greece, Denmark, Turkey, Italy, Chile, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Tunisia.

One advantage the Garand has over the M-14 is not combat related, as Hopkins pointed out. Its balance and smooth lines made it the ideal choice for complex exhibition drill, in which the rifle is spun in various directions, tossed, and caught like a baton in the hands of an expert. Said Hopkins, “I received a few lessons in the art from one sergeant first class—a tall, rangy veteran from the hills of West Virginia—but never came close to his astounding dexterity. He eventually formed a color guard within our company. As to the rifle itself, he always said he preferred the 1903 Springfield to the Garand for its superior balance in [fancy drill] movements. I’ve heard the same from other drill instructors.”

Meanwhile, the M-1 Garand is still used by the famous U.S. Marine Corps Silent Drill Team, the Norwegian Royal Guards Drill Team, and Reserve Officer Training Corps units.

After Retirement: John Garand and His Rifle

After providing the U.S. armed forces with an incomparable weapon in World War II, John Garand remained at the Springfield Armory as a consultant, believing that he would receive some kind of compensation. But, although his work was widely acknowledged, no such reward came. He retired in 1953, and died quietly at the age of 86 in Springfield on February 16, 1974.

Today, his M-1 rifle is prized by gun dealers, collectors, and shooters. Tom Laemlein, author of The M-1 Garand, said, “The Civilian Marksmanship Program scours the world to bring these old soldiers back home. In this new gun world of plastic and bare metal, the M-1 rifle remains a symbol of enduring beauty and American craftsmanship. From the tables at a gun show to the parade grounds to the rifle range, the M-1 rifle is an unmistakable icon of American firepower. Like the man said, it is a man’s gun.”

I have a Springfield made Garrand. It is the pride of my gun collection. Whenever I take it to the range (yes I still shoot it), it never fails to draw attention. One instance, a lady asked if she could shoot it. She fired it once and was ear to ear in smiles. She tried to hand the rife back to me. I told her to finish the clip. When done, she said it was an amazing experience to fire a Garrand.

My dad carried one while he was with the 10th Mountain Infantry Division during WWII.

While in Jr ROTC at Brown High School in Atlanta and later in Sr ROTC at Georgia State College, we were issued Garrand M-1 rifles. At those times I wished that I owned one but never did.

The author is incorrect in stating the M14 was lighter than the M1. The M1 weights 9 pounds and the M14 weighs 11 pounds. Also, the 20-round box magazine of the M14 is obviously heavier than the 8-round clip of the M1.