By Mark Simmons

‘‘As I floated down, the whole dropping zone seemed to be on fire; tracer bullets had set the tinder-dry stubble alight. There was no time to get my bearings before I landed with a hell of a thwack on my back in a deep ditch. I felt something warm trickling down my leg. ‘Oh my God’ I thought, ‘I’ve been hit!’ I pulled my hand away and it was water. My water bottle had burst and was crushed flat. When I had got my breath back I picked myself up and set about gathering up the rest of my chaps and finding our weapon containers. Fortunately, we were all complete, but two of our weapon containers were missing.”

So recalls Lieutenant Peter Stainforth, 1st Parachute Squadron, Royal Engineers, of the 1st Parachute Brigade landing near the Primosole Bridge on the night of July 13, 1943, in Sicily.

Operation Fustian

Three days earlier, Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily, had begun with the British and Canadians landing on the beaches to the south of Syracuse on the Pachino peninsula, while the Americans landed farther south and west on beaches near Gela.

The beach landings by General Bernard L. Montgomery’s Eighth Army were successful. The Italian coastal defenders put up a weak resistance and had their coastal batteries silenced by naval gunfire or by assault troops. By 8 am, July 10, the British 5th Division had entered Casabile and marched on past Syracuse, diverting some troops into the city, while the main force struck north along the coastal road toward Augusta. However, early on July 11 it ran into Group Schmalz, a battlegroup of the 15th Panzer Division at Priolo, well dug in and supported by Tiger tanks and antitank guns, which brought the advance to a halt. The British 50th (Northumbrian) Division waded ashore at Avola to the south, passing quickly on to Casabile. Farther south the XXX Corps, made up of Highlanders and Canadians, was pushing inland against light opposition.

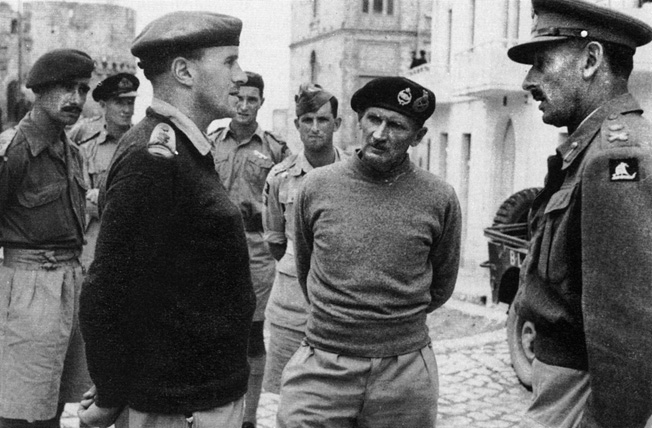

On July 11, Montgomery arrived at Syracuse, the port having fallen virtually undamaged, with his tactical HQ from Malta. He was keen to give Operation Fustian—the British airborne portion of the invasion—the go-ahead.

Lieutenant Colonel John Durnford-Slater, commanding officer of No. 3 Commando, was summonedto XIII Corps headquarters in Syracuse to receive orders for a new attack that night, July 13. He met General Montgomery, Lt. Gen. Miles Dempsey, commander XIII Corps, and Admiral Rhoderick McGrigor on the quayside near the old officer’s quarters of the Italian Navy; Eighth Army troops and equipment were pouring ashore nearby. Monty was in high spirits and eager to use his special forces to speed the advance.

Last Minute Planning For the No. 3 Commandos

This mission was assigned to Durnford-Slater’s Commandos and the 1st Parachute Brigade landing behind enemy lines that night to seize important bridges on the road north for XIII Corps. The Commandos would land from the sea near Agnone, advance inland, and take and hold the Ponte dei Malati Bridge over the River Leonardo. The 1,856 paratroops dropping from the air would take the Ponte dei Primosole Bridge, the only bridge over the River Simeto, five miles to the north. Seizing and holding the bridges would open the route to Cantania and forestall any attempt by the enemy to establish defensive lines on the two rivers.

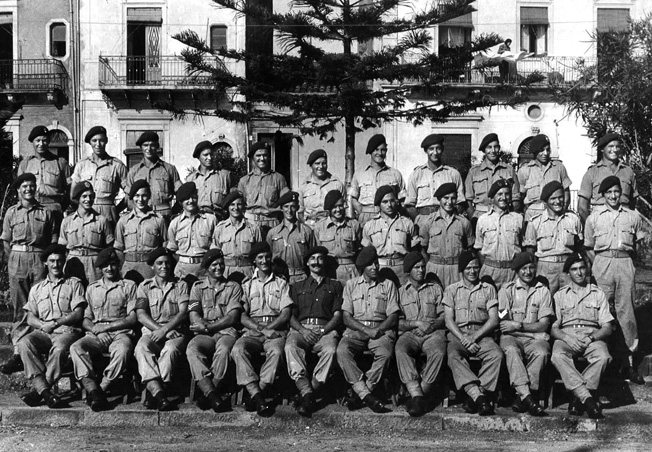

No. 3 Commando had already been in action; at midnight on July 10 it had come ashore from the assault ship HMS Prince Albert south of Syracuse to capture a coastal battery near the town of Cassibile. Although there was some small-arms fire directed at the Commandos, they got ashore dry and without loss, and quickly captured the battery.

Durnford-Slater was concerned with the lack of time to plan the Agnone landing, but intelligence indicated the Malati Bridge was only held by Italians and not in strength. But Monty was positive: “Everybody’s on the move now. The enemy is nicely on the move. We want to keep him that way. You can help us to do that. Good luck, Slater.”

The landings were planned in two waves, two troops of the first landings, 1 and 3, would push forward straight away to take the bridge. The others would hold the beach waiting for the second wave to come ashore. Further troops would then move inland, and 4 Troop would send out patrols to make contact with the paratroops at Primosole Bridge while another would link up with 50th Division advancing up the Catania Road, which was expected to reach them at first light on July 14.

1st Parachute Brigade

If No. 3 Commando’s plan was last minute, 1st Parachute Brigade’s scheme to capture the Primosole Bridge in Operation Fustian had been planned for months. The commandos were supposed to have gone in on the evening of July 12, but Eighth Army had been delayed and the operation was postponed. At 4:30 pm the next day the final approval was given.

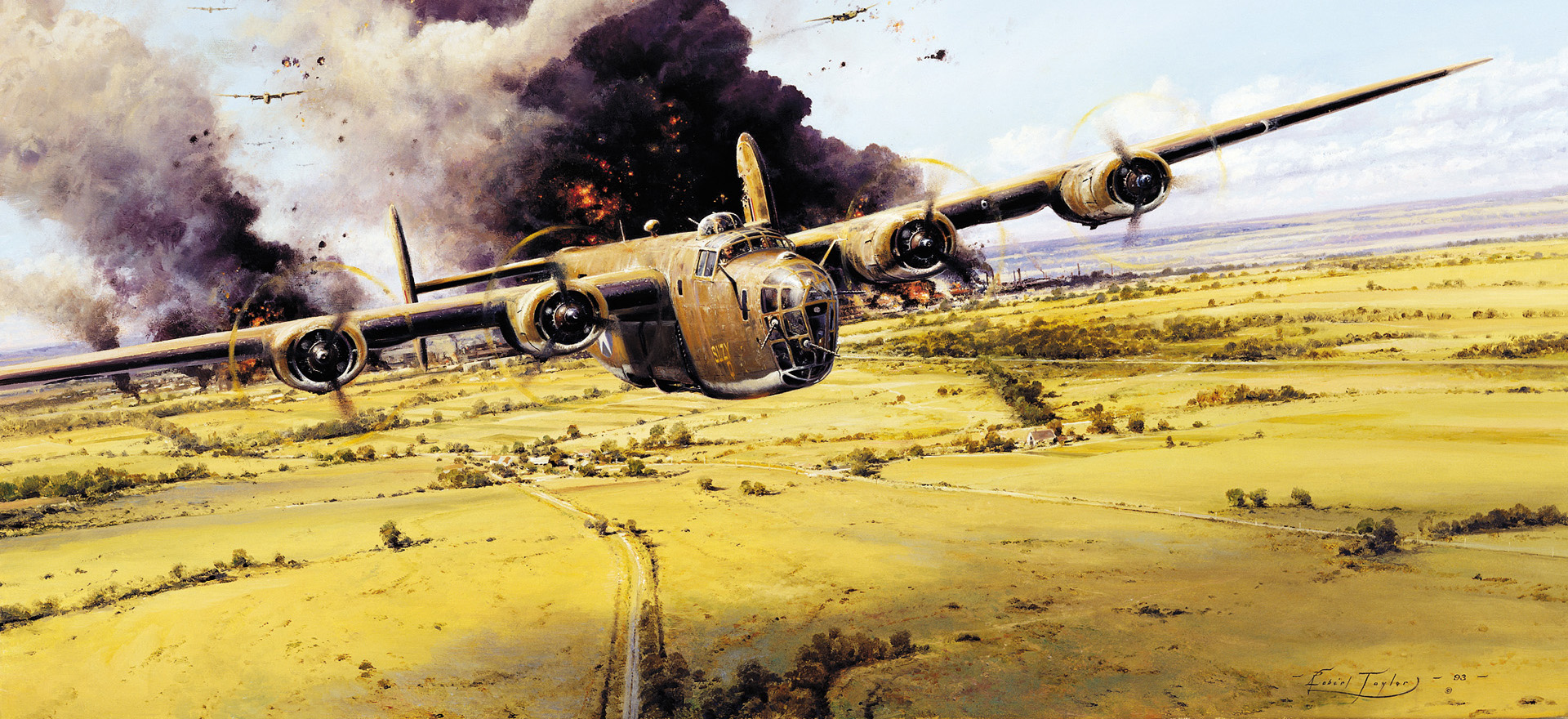

Lieutenant Colonel Alistair Pearson commanding 1st Parachute Battalion was frustrated: “The airfield was a sandy strip in the desert. We got there at midday and the only shade was under the wings of the Dakotas [transport aircraft]. We lay underneath and waited and slowly baked. By the time we got the code word, the problems of the Airlanding Brigade had filtered back. The fact that a large number of our aircraft had been shot down by friendly naval vessels did not help our morale.” In fact, more of the gliders had been released at the wrong time, many falling into the sea, and exploding flak from the defenders had blinded the inexperienced pilots.

The 51st U.S. Troop Carrier Wing would carry the British troops in 105 of its Douglas C-47 transport aircraft. This was aided by 11 British Albemarles from the Royal Air Force’s 38th Wing. The 1st Parachute Brigade’s 1,865 men would be carried in these aircraft, while heavy equipment would be in 19 gliders towed by more RAF Albemarles and Halifaxes—and carrying 10 6-pounder antitank guns and 18 jeeps along with 77 gunners.

According to the plan, the three parachute battalions would land at the same time all within two miles of the bridge. The 1st battalion would capture the bridge; the 2nd would land to the south and the 3rd to the north to prevent enemy incursions. The gliders would also land in the same zones. At 10 pm the aircraft began to take off.

The Primosole Bridge, spanning the Simeto River, was surrounded by olive and almond groves and vineyards interspaced with tree-lined fields. It was constructed of steel girders, 400 feet long and eight feet above the river. Four pillboxes had been constructed on the bridge, two at each end. The bridge on Highway 114 was 10 miles from Lentini to the south and seven miles from Catania to the north.

Commandos Hit the Beaches

At 9:30 pm, HMS Prince Albert, having earlier dodged an E-boat attack, began lowering its assault boats containing No. 3 Commando. As the boats ran into the shore, the whole world seemed to have gone mad. Catania could be seen under bombardment to the north. Very lights and tracer bullets to the west criss-crossed the sky, and to the south an antiaircraft barrage and star shells over Syracuse lit up the shore. Overhead, the Dakotas and glider tows roared toward Primosole.

With the boats about 200 yards from shore, the Germans opened fire and the Commandos returned fire as best they could from their rocking craft. With the near collapse of the Napoli Division the day before, the whole Axis line had been in danger of disintegration, so troops of the 1st German Parachute Division and the Hermann Göring Division had been moved in to plug the gap.

The Commandos quickly overcame the two pillboxes on the beach. Major Peter Young marshalled 1 and 3 Troops and set off quickly for the bridge, which was five miles inland.

The country was difficult to cross at night, covered in cacti and shrubs, interspaced with vineyards and deep streams, but it got easier when the troops picked up the railway line leading to Agnone railway station and on to the objective. The Commandos even bumped into a group of British paratroops who had been dropped well to the south of their objective. They were invited to join the Commandos but declined, moving north to try and reach the Primosole Bridge. By 3 am, Major Young and his troops had reached the River Leonardo and the northeast end of the Malati Bridge, 250 yards long.

The pillboxes there, manned by Italians, soon fell to grenades through the loopholes, and the demolition charges on the bridge were removed. The Commandos then deployed around the bridge, through orange groves and shallow ravines, building defensive positions with rocks, as the ground was too hard to dig in.

The second wave was late reaching the beach, for the LCAs (landing craft, Assault) returning from the first lift got lost on the way back to the ship. Reloaded with troops and again on the approach back to the beach, the LCAs came under fire. However, the escorting destroyer HMS Tetcott blinded the defenders on the cliff with smoke shells. By dawn Durnford-Slater had 200 to 300 men in position armed with light platoon weapons.

High Casualties For the Paratroopers

Earlier during the night, the 1st Parachute Brigade’s aircraft suffered a similar fate to that met by the American pilots during in the invasion. Many were mistakenly hit by antiaircraft fire from Allied ships, and as they neared the coast they were hit by the enemy flak barrage. Some were shot down in flames. Others broke formation, dropping the paratroops over a wide area, one stick being dropped as far away as Mount Etna. It was a rough ride for men crammed inside the bucking, twisting aircraft, while others were released at too low an altitude, resulting in horrendous injuries.

Lieutenant Colonel Alistair Pearson, in one of the planes, recalled, “I thought we were going in too fast. We seemed to be going downhill as well. Out I went over the DZ and I didn’t think my chute had opened, because I was down on the deck as soon as I’d jumped. I’d gone out number ten, my knees hurt, but I was all right; my batman at number eleven was all right but the remainder of the stick all suffered serious injuries or were killed.”

Less than 20 percent of the brigade was dropped in the correct locations, while a further 30 percent were taken back to base. It was later confirmed only 12 officers and 283 other ranks took part in the battle.

Together with his batman, Private Lake, Brigadier Gerald Lathbury, the brigade commander, headed for the Primosole Bridge in the dark; they had been dropped three miles away. He had jumped with his stick at 11:30 pm from a height of about 200 feet; fortunately for Lathbury, he had landed on soft, plowed ground. The two men paused briefly en route to pick up weapons from a container. There they met other members of the brigade HQ. Farther on they met Lt. Col. Johnny Frost and 50 men of his 2nd Battalion making their way to the objective. Lathbury divided his force into four sections but, arriving near the bridge, he learned that the 1st Battalion had already taken it. However, he was concerned that no radios seemed to have survived the landings so far.

The Fight For the Bridges

Through the night, small groups of paratroops continued to straggle in to the bridge. Frost took his men to high ground overlooking the bridge, while Lathbury deployed another 40 men either side of the river; during the day another 120 men reached the bridge where the battle had already begun.

Lieutenant Peter Stainforth saw the battle develop: “The Germans had put barbed-wire road blocks at both ends of the bridge, but opened them up to allow a truck towing a field gun to pass through just as our assault party charged in. In the firefight that followed. Brigadier Lathbury was on the receiving end of a grenade and got several splinters in him.

So when I came up there was the brigadier, trousers around his ankles, bent over, having shell dressings applied to his backside. As mine was the only sapper section to arrive, the brigadier told me to get the demolition charges off the bridge as quickly as possible.”

The Italian pillboxes at either end of the bridge contained useful weapons that the paratroops quickly turned against their former owners: several Breda heavy machine guns well supplied with ammunition. Covering the roads were two Italian 50mm guns and one German 75mm antitank gun in concrete emplacements. These, too, helped to stiffen the paras’ defense.

To the south at the Malati Bridge, the Commandos, with daylight, came under pressure but initially, as Durnford-Slater indicates, had “a marvellous time shooting up everything which came and causing complete confusion.” A PIAT (Projector, Infantry, Anti-Tank) on the bridge knocked out a German ammunition truck that blew up spectacularly.

However, heavier German units were joining the fight. A Tiger tank started shelling the bridge, knocking great lumps out of the pillboxes and bombarding and machine-gunning the meager cover to which the Commandos clung. Casualties began to rise.

German Reinforcements Arrive

More German tanks arrived during the morning, together with three battalions of a panzer grenadier regiment along with an Italian group of tanks and infantry.

About 5:20 am, Durnford-Slater held a brief conference with Major Young and acknowledged they were rapidly losing control of the situation. There was no sign of the 50th Division. Casualties caused by mortars and tanks were increasing.

More Commandos had arrived from the beach. Captain Pooley tried to work his way to the enemy flank with 5 and 6 Troops but was driven back by heavy fire; the Tiger tank was the main cause of the Commandos’ difficulties. Lying among cypress trees on the other side of the bridge, almost hull down, it was out of range of the PIATs, and to approach it over open ground was suicide.

Vastly outnumbered and with nearly a third of his men killed or wounded, Durnford-Slater had no choice. He ordered his surviving men to break into small groups and make their way back to British lines. Most of them did, although odd groups, cut off, continued the fight, keeping the bridge under fire.

Over 150 officers and men were dead, wounded, or missing from No. 3 Commando, but they had held the Malati Bridge and removed the demolition charges, so it was still serviceable when 50th Division finally reached it.

Five miles to the north, an equally desperate fight was taking place at the Primosole Bridge over the Simeto River, where the airborne troops had stirred up a hornets nest and were coming under increasing enemy pressure. The British paratroops held both ends of the bridge, frantically fighting off continuous infantry attacks with rifles and Bren guns, bombarded by artillery and mortar fire, and even strafed by Focke-Wulf 190 fighter bombers. Again and again the Germans tried to take the bridge by storm.

After the heavy losses suffered by his parachute and glider forces during the invasion of Crete in May 1941, Hitler had decreed no more airborne assault landings. But local German commanders in Sicily decided to override the Führer’s order and called for a parachute drop by the 4th Fallschirmjäger Regiment at the Primosole Bridge.

Gradually the German paratroops of the 4th Fallschirmjäger, who had been dropped accurately into the area an hour before the British landings, worked their way close to the bridge and into the reed-covered river banks.

“Don’t Let the Enemy Reform”

At about the same time that the York and Lancaster Regiment, the lead element of the 50th Division, was moving slowly north on the Lentini road, the 4th Armoured Brigade was coming forward from Augusta, but both ran into strong resistance from Group Schmalz. The largely German group consisted of the 115th Panzergrenadier Regiment, 3rd and 4th Parachute Regiments, and three fortress battalions.

The previous day, 50th Division’s lead battalions of the 69th Brigade had reached Sortino but were exhausted. Just after dawn Maj. Gen. Sidney Kirkman came up to see Brigadier Edward Cooke-Collis, urging him not to rest but to push on to Lentini. Kirkman said, “Don’t let the enemy reform,” insisting that there was little in front of him at the moment, but tomorrow he would have to fight for the ground.

Soon Kirkman was called back to Miles Dempsey’s XIII British Corps HQ. There Montgomery outlined the plan to take the bridges on the route north. He ordered him to get his men moving “at all possible speed,” which was what Kirkman had been trying to do; no doubt he felt the journey back to headquarters a waste of precious time.

Retaking Malati Bridge

The 50th Division’s drive from outside Sortino had to reach the Primosole Bridge by the morning of July 14. Taking it would involve the 69th Brigade making an advance from Sortino to Lentini via Carlentini along a single-track road. The second round would take them onto the Malati Bridge and the relief of No. 3 Commando, and then on to Primosole. On the 50th’s right, coming up the coastal road, would be the 5th Division, both roads converging on Carlentini.

All afternoon and late into the evening of July 13, the 69th Brigade pressed forward. Both Generals Kirkman and Cooke-Collis were close to the rear of their lead battalions, but it was becoming obvious that strong positions in front of Carlentini would require a full-scale assault to clear the way before they could continue on to Lentini that night. The advance was already behind schedule.

Dempsey at XIII Corps HQ was worried, but it was too late to postpone the airborne operation again, and the Commandos were already embarked at sea. The 69th Brigade had no choice but to press on, as any further delay would give the enemy time to blow the two bridges.

Cooke-Collis’s tired battalions carried on. A heavy rolling artillery barrage descended on Carlentini that night, as the 1st Airborne Brigade’s aircraft were leaving Tunisia. The next morning at 8:30, the 7th Green Howards attacked Monte Pancoli as it was blasted by divisional artillery and long-range fire of heavy mortars and Vickers machine guns. The hill finally fell, and the advance was resumed into Carlentini.

The Green Howards struggled on to Lentini, but thankfully here the enemy lacked the high ground and British artillery and tanks blasted a way through. With the fall of Lentini, the 5th East Yorkshire took over the lead to the River Leonardo and the Malati Bridge; they were delighted to find it still standing. With the light fading fast, the bridge was captured after a short firefight.

Critical Naval Support

The advance was now taken up by the 151st Brigade, with the 9th Durham Light Infantry and tanks of 4th Armoured Brigade leading toward the Primosole Bridge. That day the fight at the bridge had been a desperate business.

On three hills covering the southern approaches to the bridge, Frost (2nd Battalion) and about 140 men were trying to hold off a growing mass of the enemy, retreating away from 50th Division.

On the bridge itself, Lathbury’s men were holding on against pressure from the north. The situation was fast developing into a back-to-back action. However, help was on hand from an unlikely source—Lieutenant Peter Stainforth.

He said, “We were the brigade’s reserve on the south side and could do nothing useful at the moment. Pearson [1st Battalion] was holding off the Germans on the north side and there was quite a lot of firing going on up in the hills where John Frost was.

“He had an artillery officer with him who eventually made contact with a Royal Navy cruiser, the Arethusa [it was actually the HMS Mauritius of Rear Admiral Cecil H.J. Harcourt’s 15th Cruiser Squadron]. Things apparently had got pretty desperate until she began sending over six-inch shells, which made a hell of a difference.” Also providing naval fire during Operation Husky were the Royal Navy cruisers Newfoundland and Arethusa.

The accurate naval fire blew the spirit out of the German attack. Each time they tried to reform for an assault, crashing salvoes were brought down on their heads, reducing them to sniping and small-arms fire. The forward observation officer who brought down the cruiser’s fire was Captain Vere Hodge of the Light Regiment Royal Artillery.

Withdrawal From the Primosole Bridge

Lathbury at the Primosole bridge had little idea what was going on behind him. The reduction in noise from that direction gave him the feeling perhaps Frost and his men had been overrun. However, Frost could see what was happening below him but was unable to use the naval firepower to support Lathbury’s men as they were too close to the enemy.

By late afternoon and with no sign of the 50th Division, Lathbury decided to pull back the remains of 1st and 3rd Battalions across the river and abandon the northern end. Alistair Pearson noted, “With only about 200 men, including a couple of platoons of 3 Para, I formed a defensive position around the approaches to the bridge. The Germans put in a series of attacks in the afternoon. We weren’t in any danger of being overrun but we were suffering casualties and were running short of ammunition. But I considered we could hold out until dark.

“However, at 1830 hours I was ordered to withdraw by Brigadier Lathbury, with which I disagreed. But in the end I had to do as I was told and withdrew my battalion up to the hills. Before I withdrew I took my provost sergeant ‘Panzer’ Manser and my batman, Jock Clements, and made a recce of the river bank because I had a gut feeling I was coming back again. It was stinking and the mosquitoes were there in their millions. About 500 yards along I found a ford where we crossed and made our way back to the battalion lines.”

The retreat to the southern end of the Primosole bridge for a while produced a stronger position with more concentrated firepower. However, the Germans brought up antitank guns close to the northern end of the bridge and blasted the pillboxes apart.

One by one the casemated guns fell silent, and ammunition ran out. The Brits’ own Vickers machine guns were down to their last belts of bullets. A final well-planned and concentrated German attack down both sides of the river covered by the smoke from burning reeds got among the British paras. In places the fighting was hand-to-hand. With no sign of relief, Lathbury was forced to order another withdrawal. The order was passed, and the paras melted away in the failing light toward the hills still held by the 2nd battalion. It was about 7:30 pm.

Peter Stainforth recalled, “Colonel Hunter [he probably meant Major David Hunter], thinking that the Germans might cross the river and take us in the rear, asked me to go with our Bren gunner onto the right flank where there was a Vickers machine gun. By this time the 1st Battalion, almost out of ammunition, had withdrawn to the south side of the bridge, so the Germans, having been reinforced from Catania, turned their full fury on us. Lathbury had no alternative but to abandon the bridge. The brigade major, who crawled along to our position, gave me the impression it was every man for himself. I must have been one of the last to leave because there was hardly anyone about.”

Some of the men, including Lt. Col. Alistair Pearson, made it back to Frost’s 2nd Battalion; however, Peter Stainforth had to make a long detour west to bypass the enemy, at times hiding in scrub, which took him out of the fight.

Planning an Assault Across the River

A short time later, at twilight, Bren gun carriers of the 9th Durham Light Infantry supported by tanks of the 4th Armoured Brigade came into view below the positions of the remnants of the 1st Parachute Brigade.

The arrival of fresh troops denied the Germans any attempt to move forward or to lay new charges to blow the Primosole bridge. They were followed by the other two battalions of the Durham Light Infantry, and their commander, Brigadier R. H. Senior, who was able to establish a large perimeter at the southern end of the bridge. His men were too worn out to launch a full-scale attack that night, but preparations were made for an assault across the river at 7:30 the next morning.

That night, A Company, 8th Durham Light Infantry, cleared the southern end of the bridge, holding on in slit trenches and under intense mortar and machine-gun fire at the slightest movement. With first light, Royal Engineers came forward to clear mines.

On the opposite bank, various units of the German 1st Parachute Division were also digging in. These included machine-gun and engineer battalions of General Richard Heidrich’s division, supported by a battery of paratroop artillery, two 88mm guns from a flak regiment being used in the ground role, and remnants of two Italian battalions. Further north around Catania, men of the Schmalz Group were reforming, while the 4th Parachute Regiment, largely complete, was ready to move south.

Leading the British assault unit the next morning, July 15, would be the 9th Durham Light Infantry, wading the river and supported by field artillery and tank fire. The attack lacked imagination and would require considerable courage. The troops would be exposed crossing the river either side of the bridge, the covering barrage would have to lift too early to cover the infantry, and the German paratroops were well dug in on the other side.

A few platoons managed to struggle across under a withering fire. Some determined men got to hand-to-hand fighting but were too few to storm the positions and had to fall back. The London Times reported on the fight for Primosole bridge that the German troops “fought superbly. They were troops of the highest quality, experienced veterans of Crete and Russia: cool and skilled.”

As Alistair Pearson watched the assault of the 9th DLI that morning, he may have been impressed by the skill of the German defenders, but he was not by the handling of the British troops.

“I was called up to Durham’s Brigade HQ to see what the next move was,” he said. “I listened in amazement as the brigade commander put forward the idea of another attack that afternoon. I said, in a voice louder than I should have done, ‘If you want to lose another battalion, you’re going the right way about it.’ There was a deathly silence as the two brigadiers gave me a long look.”

Luckily for Pearson, Lathbury was also there, so he did not get a dressing down; instead, his brigadier persuaded the other senior officers to hear him out. Lathbury told them he could take two companies of 8th DLI across the river upstream from the bridge and place them on the flank of the enemy.

“The Battle Was Very Noisy and Very Bloody”

Shortly after 2 am, Lathbury led his men across the Simeto at a point where the river was 30 yards wide and four feet deep. Once across the river, they turned east and moved toward the bridge. As soon as they attacked, the signal of a Very light (flare pistol) was seen; this was the signal for the rest of the battalion and supporting arms to storm across the bridge to form a lodgement.

The flanking force managed, by surprise and with grenades and bayonets, to force its way through. The German paratroops not killed in the rush withdrew into the vineyards and olive groves close to the road to Catania. By dawn the bridge had been crossed by the two remaining companies of the 8th DLI with tank support. They eagerly pressed on but soon came under fire from all sides, and the Durhams were soon in serious trouble. They had managed to get only 300 yards beyond the northern end of the Primosole bridge when, according to the divisional history, “Lively fire was exchanged on both sides at ranges decreasing to 20 yards.”

The main holdup was caused by two 88mm guns that had knocked out four Sherman tanks. The tanks were stalled by these well-sighted guns, and the infantry could not move either without armored support.

Sergeant Ray Pinchin of A Company, 8th DLI, recalled, “The battle was very noisy and very bloody. It caused us all a lot of grief. After we’d crossed the river and taken up a defensive position behind a low stone wall, I had my section dig in and we all had our heads well down.”

Brigadier Senior crossed the river to assess the situation and got promptly pinned down himself on the other side. General Kirkman then arrived and had to communicate with his brigadier by radio. With the attack badly stalled and even the tenuous lodgement in some doubt, Kirkman informed general HQ that the division would be unable to support an amphibious plan to capture Catania.

Montgomery agreed to a 24-hour postponement of the landings. He then set off for the front along with Dempsey to see things for himself. Arriving at 50th Division HQ, Monty was told that another attempt to secure the front on the north side of the Simeto would be made that night.

Abandoning the Plan

At 1 am on the 17th, the 6th and 9th DLI crossed the river via the “Pearson” ford to the left of the bridge. Again they came in on the flank, but this time the attack was made by two battalions instead of two companies. The Durhams reached the Cantania road and overwhelmed the defenders—German paratroops and detachments of the Hermann Göring Division—and dug in just in time to beat off a counterattack by German paratroops and tanks.

More British tanks got over the river, expanding the bridgehead and prompting isolated groups of the enemy to surrender. The cost had been high; the two assault battalions of DLI lost 220 men. Of the 292 officers and men of the 1st Parachute Brigade who reached the Primosole bridge, 27 had been killed and 78 wounded; many were also missing. Some 400 other members who never reached the bridge had been killed, injured, or captured during the landings.

With the benefit of new intelligence, Montgomery had to reassess the situation. Between the River Simeto and the city of Catania on a fairly narrow coastal plain were a lot of determined German troops with new units arriving, like the 15th Panzergrenadier Regiment from the 29th Panzergrenadier Division, which had gone into action late on July 16.

It was obvious now that the 50th Division would find it difficult to break out from the Simeto bridgehead and link up with seaborne landings further north. The amphibious plan was abandoned; a new way would have to be found to get to Catania.

Monty Visits His Men

Alistair Pearson came across Montgomery when the 1st Parachute Brigade was withdrawn to Syracuse. Pearson was asleep in the front seat of a moving truck; his batman Jock Clements woke him to let him know Monty was just behind their small convoy. The khaki Humber staff car swept past them, and the driver indicated they were to stop.

Pearson takes up the story: “I thought a rocket [chewing out] was impending for being asleep, but not so. He greeted me by name like a long-lost friend and congratulated us on our efforts and then said he’d like to talk to the men.

“My RSM [Regimental Sergeant Major] who was right behind me was pretty quick-witted and moved off to wake them. But he was a clever bugger, old Monty. He got his ADC to throw some packets of cigarettes into the trucks where the men were.

“Then he said, ‘Walk with me, Pearson.’ So we went about 200 yards down the road while he told me that although our casualties had been high, the cost was worth it. He then walked slowly back again. When we got to the trucks he was greeted by cheering men all smoking Monty’s fags [cigarettes] and saying, ‘How’s Alamein, sir?’ There he was lapping this all up, all the cheers. It was very, very clever how he knew where I was and a great morale raiser.”

No Quick Victory at Catania

The positive air Montgomery was skilled at exuding was good for morale; however, his race against time to take Catania was over. He had gambled on a quick victory and failed. The campaign ahead would be prolonged with heavy fighting. The hope of cornering large numbers of the enemy was gone. Catania did not fall until August 5, and Eighth Army reached Messina on August 17, having had to fight its way around both sides of Mount Etna.

Indeed, it was true that some parachutists had landed on Mount Etna; Captain Victor Dover, adjutant of the 2nd Battalion, and his stick had been dropped there. Dover and another man took a month to find their way back across country to Allied lines; the rest were captured.

Montgomery was impressed with the exploits of No. 3 Commando at the Malati Bridge, which he renamed “3 Commando Bridge.” A plaque with that name remains on the bridge today. Although it is no longer the main road, being overshadowed by the autostrada, a stone pillbox remains at one end to commemorate the battle.

Fantastic write up on Operation Fustian. A course I am currently attending, has me writing a Battle Analysis paper for this skirmish, and I’ve cited you and a few others.

The one thing I had the most trouble with is Axis force numbers. In a few accounts, we’re looking at roughly 1400 paratroopers from the 1st DIV — the only detailed number account. Not sure how…?

But then there’s nothing on the 1st or 4th Fallschirmjager, the 3 Battalions of Panzer Grenadiers, or anything about the Italian Coastal Divisions – aside from them sounding like voluntold recruits that later changed sides.

Have you read or found any accounts of closer or precision numbers?

Because I tried to hypothesize based on the prefix of each of them: Regiment, Division, Battalion, Company — but this then would assume that 3 BNs worth of soldiers are anywhere from 1200-3000 soldiers … and then I can’t fathom, in the given terrain, that less than 350 soldiers against tanks, planes, and mortars — managed to survive and overthrow upwards of 10,000 soldiers.

They surely didn’t have Leonidas with them, haha…

Great read on a topic I have not read much about previously. Funny how the Bren Gun Carrier pictured closely resembles a US Scout Car— more attention needed to labeling photos accurately. I have noticed errors in other articles as well. Cheers

Looks like shades of Market-Garden. Good write-up. Patton’s operations in Sicily overshadow those of Montgomery.