Dear Editors,

During a recent visit to Tunisia, I saw this Wehrmacht fuel barrel dated 1942, stuck in the sand near Mareth. It is a reminder of the desert war in North Africa where at the Mareth Line, the last major battle of Rommel’s Afrika Korps was fought against Montgomery’s 8th Army.

David Stirling

Victoria, British Columbia

Dear Editors,

I enjoy reading your magazine from cover to cover, and am always looking forward to the next issue (which can’t seem to come soon enough), but I have noticed inaccuracies in the past, as well as a few in the current issue that I feel must be addressed. In the article “Cauldron of Death” pertaining to the Demyansk Salient, in the top photo on p. 35, the caption refers to “German anti-tank vehicle.” I may be wrong, but it appears to me that this vehicle is a captured Soviet 45mm anti-tank gun in German service, and not an anti-tank “vehicle.” Another photo caption that I had a problem with was in the “Victory at Last” article. The photo in question appears on p. 63, describing 3 soviet T-34’s as they rumble through the streets of Berlin. The rear tank in the photo appears to have had its right rear external gas tank knocked off, and the clamps that secure it appear to be damaged. The tank in front of it, appears to have its hatches open—not something that a tank would normally do in urban fighting. These two factors have led me to believe that these tanks are not rumbling, but instead are disabled and abandoned. I may be wrong but these are my impressions.

Joe Stauder

Thanks for your observations regarding the photographs in the May issue. The quality of the original photos, like many that we use, makes accurate captioning impossible, so we frequently are left with the caption as it was furnished with the photo. As to whether those Russian tanks are “rumbling,” or not, only their drivers know for sure.

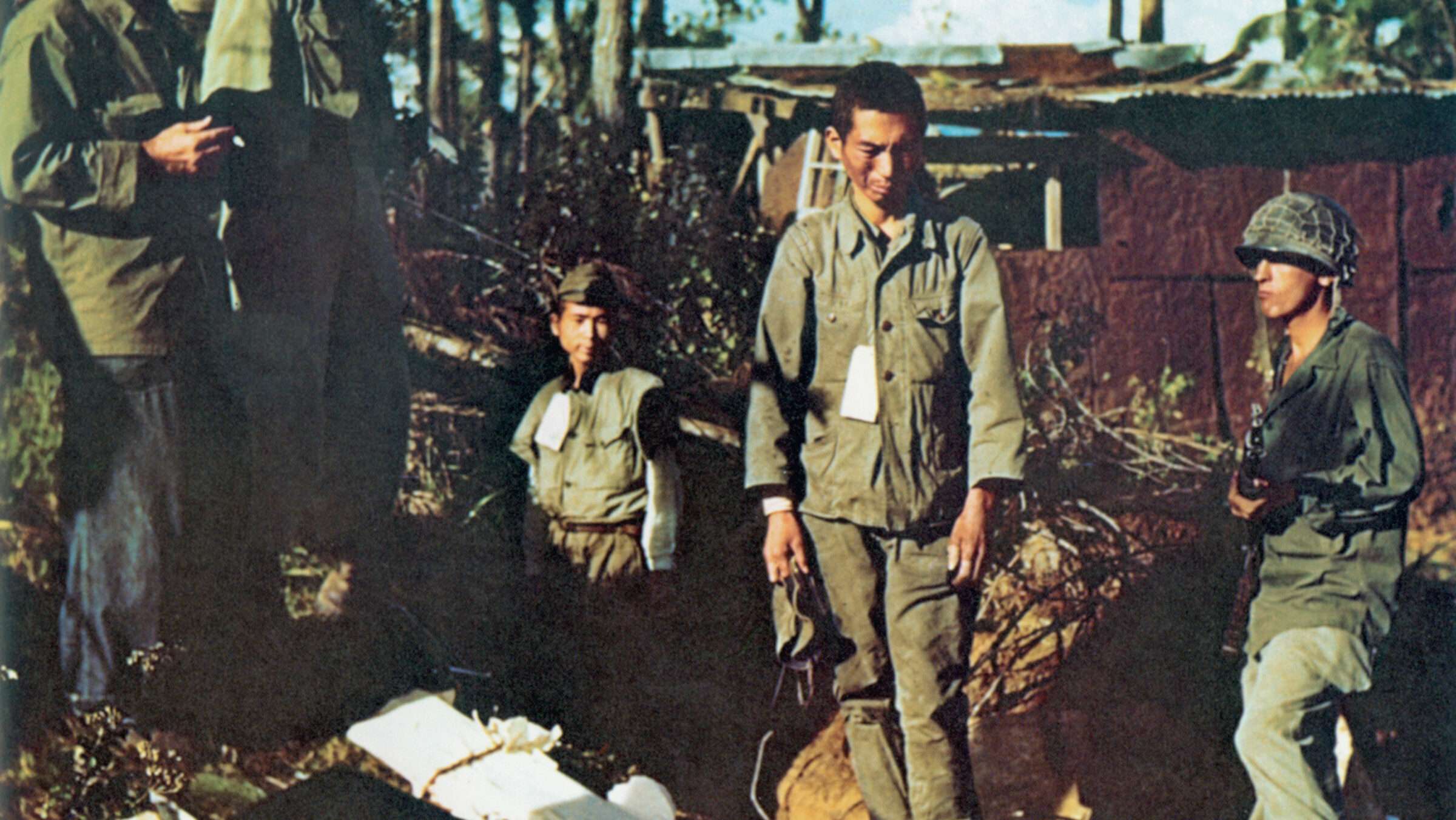

Peleliu

Dear Editors,

I just finished your last issue and was very impressed by the selections. The useless and bloody landing at Peleliu was an example of the sometimes terrible planning and underestimation of the Japanese that typified too much of the war in the pacific. Readers of the article on Nomonhan should be referred to the exhaustive two-volume study by Alvin Coox of the same name published in 1985. It has an in-depth analysis of the battles with an almost hourly step-by-step story of the campaign and the individuals involved. It is also based almost exclusively on Japanese resources.

Gene Arnold

Lake Oswego, Oregon

Slapton Sands Landings

Dear Editors,

I read with interest the article in your May 2005 issue concerning the surprise attack by German E-Boats. I was in the Combat Engineers at that time. At Slapton Sands we cleared the beaches of many British mines in preparation for the practice beach landings. We remained in the general area until the invasion. From what we were told, most of the landing troops that died wore their life belts too low and, consequently, were very top heavy and drowned. I’m not sure of the real story, but I do know that we were instructed to fix marlin suspenders on our life belts to keep the pack up under our armpits. We were on several of these practice landings, but we not present on the one covered by the story. I never saw the bodies from this landing.

Wayne Brewster

Rapid City, South Dakota

Royal Navy in the Pacific

Dear Editors,

The article on the participation of the Royal Navy in the Pacific War in your January 2005 issue was very interesting. I feel this article covered a little known aspect of WWII. The writer was correct in alluding to the fact that use of units of the Royal Navy in the Pacific War was politically motivated. The writer noted this when he stated “its creation sprang from the fertile political mind of Prime Minister Winston Churchill”. However, I think a few more details on this would have been appropriate. There were two major reasons why Churchill wanted Royal Navy units fighting in the Pacific. The first was that he was afraid that if American forces liberated the islands and territories lost to the Japanese, Britain would never get them back. They would be granted independence or turned over to the United Nations pending independence, as President Roosevelt was a rather strong anti-colonialist. A sizeable contingent of the Royal Navy in the Pacific would help prevent this from happening. Needless to say, that problem essentially disappeared when Roosevelt died in April 1945.

The second reason was that Lend Lease aid to Britain would terminate when the War in Europe ended, as Lend Lease was contingent on the recipient nation actively fighting the Axis powers. Active participation of the Royal Navy in the Pacific alongside the U.S. Navy would ensure that Lend Lease would still flow to Britain as long as the war with Japan continued. At any rate, politics aside, as Mr. Marino’s article states, the Royal Navy did make a substantial contribution in the Pacific War.

Claybourne C. Snead

Arlington, Virginia

Editor,

I found Michael D. Hull’s profile on Lilya Litvak, the Red Air Force fighter ace (WWII History, January 2005) very interesting and inspiring, although I tend to wonder about the veracity of the human interest details. Litvak’s story brings to mind boxer Maggie Fitzgerald, played by Hilary Swank, in the current Oscar winner, “Million Dollar Baby,” or kick-butt spy, Sydney Bristowe, played by actress Jennifer Gamer in the TV series, “Alias.”

The main reason I am writing, however, is to point out that women moving into roles ordinarily filled by men has a long history in Russia. The composer Alexander Borodin, whose Polovtsian dances from his opera Prince Igor are a colorful part of the concert repertoire, was a doctor and chemist by profession. One of his efforts in his professional life in 1872 was to establish medical courses for women at the university where he taught and pursued research.

Another instance of women filling men’s shoes occurred late in WWI, when the Imperial Russian Army was suffering defeat after defeat. This prompted the Russian Government (either under the Tsar or under Kerensky) to call for, and raise, a detachment of women soldiers who briefly fought the Germans. I am pretty sure they didn’t win many victories—I seem to recall their losses were heavy—but their exploits were publicized with the aim of shaming war weary, defeatist, and desertion-prone male soldiers back into a fighting spirit. This episode came to my attention perhaps 8 years ago when I watched a miniseries on WWI on public television. My VCR is broken so I can’t revisit the videotapes I made at the time and really pin down the details.

Stephen J.

Evanston, Illinois

Dear Editors,

I enjoyed reading the article on crossing the Rhine at Remagen in your March 2005 issue. In February 1978 I bought a paper weight with a pillar stone of the Remagen bridge. Along with it was a scroll encased in plastic. Mayor Hans Peter Kürsten said proceeds of this sale were destined for establishment of a museum—in one of the remaining towers located on the Remagen side—in memory of the German and American soldiers who lost their lives at the bridge. Just thought I’d share this with your readers.

William J. Zizelmann

Houston, Texas

German Me-162

Dear Editors,

Having spent a year and a half working in Norway, stories of operations there always catch my eye. Standing on the sites of these events always adds an additional level of impact to the stories. However in the Battle of Narvik, you have fallen victim to the continuing effects of wartime German propaganda. The photograph on page 42 describes a German Me-110 over a German destroyer during intense fighting on April 5th. There is an error I’d like to point out. The aircraft pictured is not an Me-110, but is actually one of only three prototype Me-162’s. The Me-162 was Messerschmitt’s entry into the pre-war Schnellbomber competition. The Me-162 has a close family resemblance to the Me-110 as the wing and tail assemblies had common components, but the glazed nose for the bombardier is a give-away. The Me-162 never saw service in the Luftwaffe, but was pressed into service—like several other German aircraft types—by the German propaganda machine. Donning non-existent unit markings, the Me-162 was often photographed and used to confuse Allied intelligence. As this photo shows a burning ship in the foreground, I suspect it is really a composite photo, manipulated by German propaganda services, and not truly a combat photo at all. The He-100, photographed as the He-113, is often seen in similar guise. Good luck in the future and thanks for a story on this lesser known theater of WWII.

Scott Flagg

Sunnyvale, California

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments