By Roy Morris, Jr.

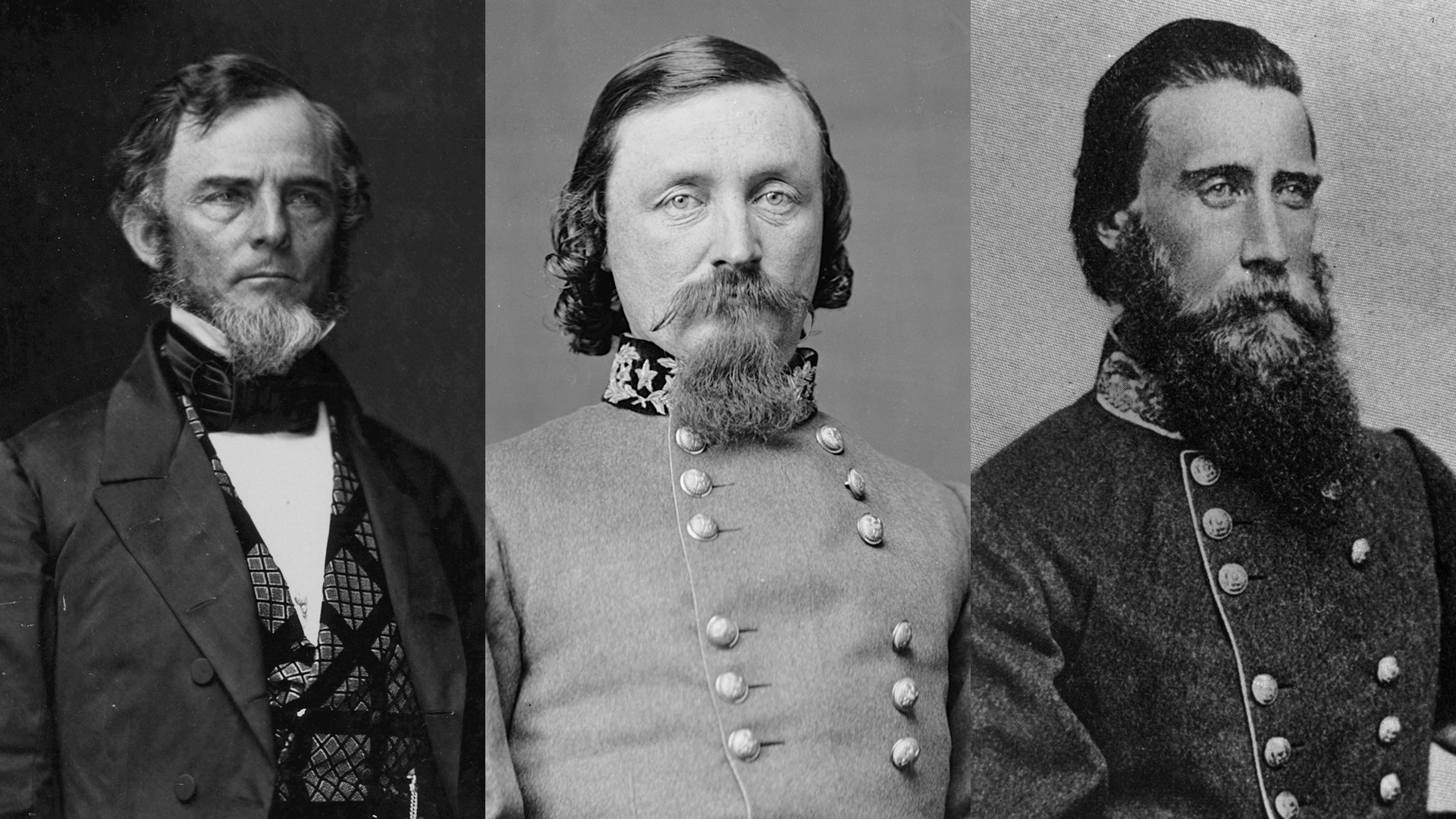

Tall, handsome, and ramrod-straight Winfield Scott Hancock perfectly embodied his flattering nickname, “Hancock the Superb.” His performance on Civil War battlefields from Antietam to Gettysburg underscored that sobriquet. Few Union generals made a more striking impression within the army than the Pennsylvania-born West Pointer.

Even more striking than Hancock—and considerably more flamboyant—was his younger counterpart, “Boy General” George Armstrong Custer. Despite graduating dead last in his own West Point class (1861), Custer parlayed a slashing, hell-for-leather style of attack into a brevet major generalship by the end of the war. His often breathtaking disregard for friendly casualties was an often overlooked part of the package.

‘Hancock’s War’ & Tarnished Reputations

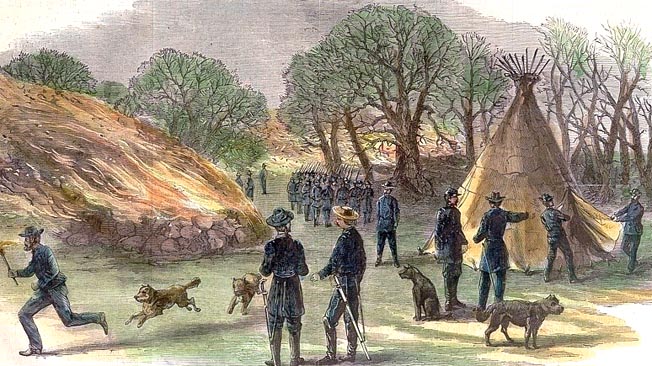

But both Hancock the Superb and Boy General Custer would find their personal and professional reputations badly tarnished in the military fiasco known—much to its namesake’s eternal chagrin—as Hancock’s War. On the windswept prairies of Kansas and Nebraska, their Plains Indian opponents would prove considerably less awed by the generals’ preceding reputations. And unlike the Confederate Army, the Sioux and Cheyenne warriors did not go in for suicidal frontal attacks and sword-swinging melees. They typically fought on their own terms, when and where it was most advantageous for them. Glory meant something entire different to Native Americans. As commander of the Military Department of the Missouri, Hancock inadvertently annoyed Indian leaders at the outset of hostilities when he lectured them at great length on their responsibilities as chiefs during a stormy parlay at Fort Larned. “I don’t find many chiefs here,” he complained. “I have a great deal to say to the Indians. Tomorrow I am going to your camp.” The chiefs, with fresh memories of the horrifying massacre of Cheyenne men, women and children at Sand Creek, Colorado, three years earlier, did not wait around for Hancock’s visit. They vamoosed.

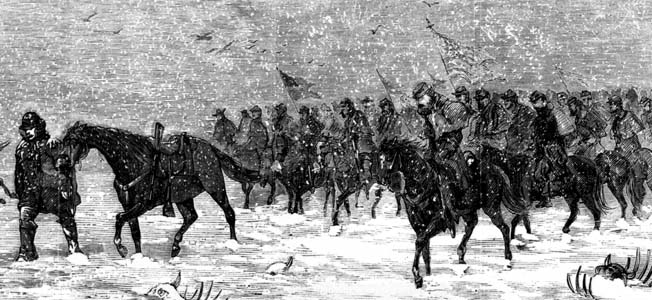

Furious at their departure, Hancock dispatched Custer and the 7th Cavalry to bring them back to camp. For the next three months, the Boy General futilely chased the tribesmen from Kansas to the Platte River in Colorado. Not once did they cooperate and offer a standing fight, although they left a trail of burned homesteads, wagon trains, and stagecoach stations for him to follow. The Indians gave Custer a new nickname—Hard Backsides—for spending so much time in the saddle chasing them.

Custer Charged With Desertion

Frustrated and embarrassed by his failure to coral the fugitives, Custer made an unauthorized trip to Fort Riley, Kansas, to visit his unhappy wife, Libbie, and quickly found himself brought up on charges of “conduct to the prejudice of good order and military discipline.” He was lucky not to have been charged with desertion. A military court subsequently found Custer guilty on all counts—he was—and sentenced him to a year’s suspension and loss of pay. The less than repentant Custer returned home to Michigan and bombarded friendly newspapers and politicians with letters blaming Hancock for his ridiculous showing on the Plains. Meanwhile, the two sides signed a mutually unsatisfactory treaty at Medicine Lodge Creek in October 1867, putting an end to the inglorious war.

His First & Only Triumph on the Plains

The next year, Custer was back in the saddle, restored to command after Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan interceded in his behalf with President Ulysses S. Grant. On the banks of the Washita River, in November 1868, he finally located a hostile Cheyenne camp. To the ghostly strains of its battle song, “Garry Owen,” the 7th Cavalry fell on Chief Black Kettle’s camp, killing the chief, his wife and 101 other Cheyenne. It was Custer’s first and only triumph over the Plainsmen. As for Hancock, the survived Hancock’s War, only to lose another battle, this one political, when he was defeated by his former Union Army comrade, General James A. Garfield, in the presidential election of 1880. By then, Custer and most of the 7th Cavalry were long since dead, slain on the banks of another river, the Little Bighorn, by some of the Sioux and Cheyenne they had chased around the Plains nearly a decade earlier.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments