by William E. Welsh

Kennesaw Mountain was an alluring sight to General Joseph E. Johnston as he fell back from Allatoona Pass in mid-June 1864 toward the Confederate supply hub of Atlanta. The boulder-strewn, heavily wooded mountain rises 800 feet above the surrounding landscape. For Johnston, it offered a solid anchor to yet another defensive position as his Army of Tennessee parried blow after blow from Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s 100,000-strong army.

[text_ad]

A graduate of the West Point Class of 1829 who was trained as a civil engineer, Johnston directed the 53,000-man Army of Tennessee to a new position on June 19 that stretched in an arc southwest from Kennesaw Mountain. Johnston’s engineers set to work immediately ordering the men to dig in on the rocky slopes of the mountain and its western spurs.

Weather Just as Much an Enemy as the Confederates

Sherman’s army had another enemy that summer besides the Confederates. That enemy was constant rainfall. Such weather was great for defense, but bad for attack. Muddy roads were nearly impassable, and the fields and woods across which the Yankees would have to attack were like swamps. Still, Sherman’s army, which actually comprised three armies—the armies of the Cumberland, the Ohio, and the Tennessee—was less than 20 miles from Atlanta.

In an attempt to throw Sherman’s army off balance, Johnston allowed hard-fighting Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood, who had fought under Robert E. Lee in the East, to lead his corps against the Union right flank at Peter Kolb’s farm on June 22. The late afternoon attack began badly, and ended even worse when Federal artillery shattered it at dusk. The Rebels lost six times as many men as the Federals.

The Battle’s Climax

Although the armies faced off for nearly two weeks at Kennesaw Mountain, the climax of the battle occurred on June 27 when Sherman ordered a two-prong attack against the Confederate line. Bowing to pressure from Lt. Gen Ulysses S. Grant, who by then was commander of all Union armies, Sherman decided to send two spearheads against Johnston’s line.

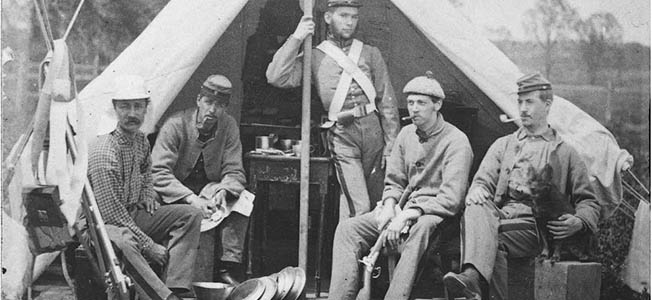

The northern prong consisted of 5,500 men drawn from Maj. Gen, John Logan’s XV Corps (Army of the Tennessee). The southern prong consisted of 8,000 men drawn from Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard IV Corps and Maj. Gen. John Palmer’s XIV Corps (Army of the Cumberland).

At 8 AM, Logan’s men swept forward toward the rebel works on Little Kennesaw Mountain, a smaller promontory of the Kennesaw ridge. It was a hellish advance through thick woods over ground where dirt, pine needles, and leaves had combined to form a mucky paste from recent rains. The Confederates had felled trees to slow the attackers’ advance. Although the Federals easily overran the Rebel pickets in rifle pits in front of the breastworks, the Federals stood no chance against the wall of fire they encountered from 5,000 butternut infantry supported by artillery on high ground. Logan’s spearhead was decimated in less than two hours.

A Careful Pick of Targets

Further south, Thomas’ bluecoats swept forward toward the daunting Southern works an hour later. The nervous soldiers, many of whom would not survive the ordeal, had been told to fix bayonets and not to stop to fire their weapons until they had reached enemy lines. The attacking force had been divided into five 1,600-man columns.

Well-protected behind breastworks carefully crafted from dirt, stone, and logs, the Confederates picked their targets carefully. Union soldiers who survived the attack recalled musketry so severe that it reminded them of a hailstorm or wind-blown rain. For the most part, the men of the Army of the Cumberland got no closer than 15 feet to the trenches. Nevertheless, some hand-to-hand fighting occurred. The failed attack lasted just three hours.

The total cost of the battle was 1,800 and 800 casualties for the Union and Confederate armies, respectively. When Sherman extended his right flank a few days later, Johnston ordered yet another retreat.

Visiting Kennesaw Mountain

Whether travelling north or south on Interstate 75, take exit 269 (Barrett Parkway) and follow signs to the visitor center, which is about three miles from the interstate. The visitor center is open daily except for Thanksgiving, December 25, and January 1.

A self-guiding auto tour has eight major stops. Fortunately, the National Park Service not only owns Kennesaw and Little Kennesaw, but also key parcels of land stretching southwest to Kolb’s Farm. The auto tour weaves its way to both sides of the lines, giving visitors a view of the battlefield from the eyes of both Northerners and Southerners.

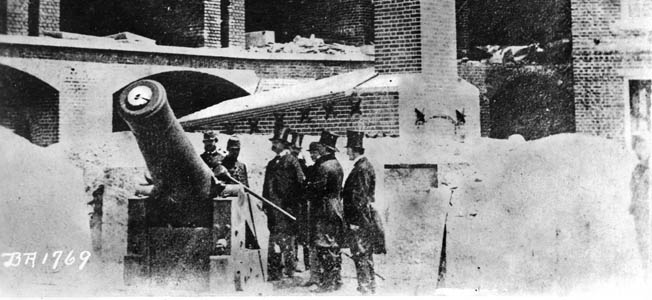

Key sites to see on the auto tour are the 24-gun battery where Union forces massed four batteries to shell the Confederates on Little Kennesaw, Pigeon Hill where the northern prong of the Union attack was repulsed, and Cheatham Hill where the southern prong was defeated. Cheatham Hill encompasses the location known as “Dead Angle” where some of the most brutal combat of the June 27 assault occurred.

Visitors can enjoy a fantastic panorama from the summit of Kennesaw Mountain. In addition to that, there are a number of other significant photographic subjects, such as the Kolb family’s farmhouse, and the Georgia and Illinois soldier monuments. A curious feature of the Illinois monument is that it is built above the opening to a tunnel dug by Union soldiers as part of a plan to detonate a mine beneath Confederate trenches.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments