by William Welsh

One of the catalysts for a major rebellion in the United States were irregular warfare in “Bleeding Kansas” from 1854 to 1861 between anti-slavery Free Staters and pro-slavery border ruffians. Another catalyst was John Brown’s raid on the U.S. arsenal at Harper’s Ferry from October 16-18, 1859. Yet another, and perhaps the most significant, was the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln to the Presidency on November 6, 1860. South Carolina was the first state to secede on December 20, 1860.

By 1861, the lines were drawn. The 22 northern states had a population of 22 million and a diversified industrial-agricultural economy, and the southern states had 5.5 million whites and 3.5 million slaves in a predominantly agricultural economy. The South was dependent on overseas markets for the sale of its main crops: tobacco, cotton, and sugar.

This Civil War timeline is not definitive, but does outline the key events of 1860 which later helped to shape the war.

[text_ad]

1861: The Road to Civil War

February 8-9 – The first seven states to secede (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas) hold a convention in Montgomery, Ala., in which they establish a provisional government, crafted a constitution, and elected Jefferson Davis to serve as president.

March 6 – Confederate President Davis calls for 100,000 volunteers to serve for one year.

April 12-14 – South Carolina forces under Maj. Gen. Pierre G.T. Beauregard fire on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. The 83-man U.S. Army garrison inside Fort Sumter under Major Robert Anderson surrenders after 34 hours of bombardment. Beauregard allows federal vessels transport the garrison to the North. Surprisingly, there were no casualties.

April 15 – U.S. President Abraham Lincoln calls for 75,000 volunteers to serve for three months to suppress the rebellion.

April 17 – Virginia secedes from the Union on the grounds that Lincoln’s call for volunteers constitutes an act of aggression. After Virginia, three more states—Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee—secede shortly afterwards.

April 19 – U.S. President Lincoln orders a naval blockade of the Confederacy.

April 20 – Virginia militia seize the Norfolk Navy Yard, and capture as prizes the steam frigate Merrimack and approximately 50 9-inch guns.

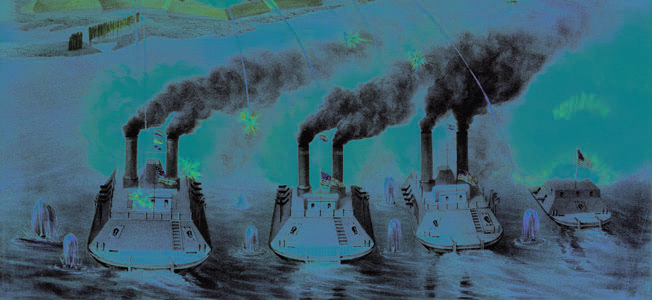

May 21 – U.S. Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott issues the final form of his Anaconda Plan, which set forth a strategy for defeating the insurrection. The plan calls for an immediate blockade of Southern ports, the recruitment of 300,000 men, and reinforcement of the remaining federal garrisons in the South. After the new recruits had been adequately trained, the initial offensive would occur in the Mississippi Valley with the aim of cutting off the trans-Mississippi states from the rest of the Confederacy. Critics dub it the Anaconda Plan because of its slow nature. It is only partially applied.

May 24 – Virginia militia deploys in Alexandria, Va., and establishes batteries that control the Potomac River approaches to the Federal capital at Washington.

June 3 – Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan oversees the advance of 3,000 troops into western Virginia to secure the path of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. A two-prong Federal night attack on Philippi in the Tygart River Valley turns out to be too complex for the green troops to carry out effectively, and the 800-man Confederate force under Colonel George Porterfield easily escapes. The Northern press mocks the performance, calling it the “Philippi Races.”

On April 19, 1861, soldiers from Massachusetts going through Baltimore to Washington were attacked by pro-southern people. Four soldiers and 12 rioters were killed. Rail traffic between the northern states and Washington was interrupted until May 13, 1861.