By A.B. Feuer

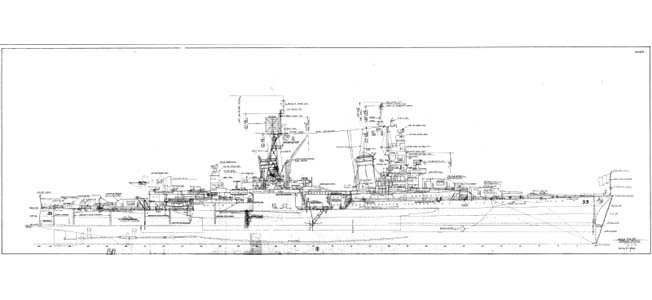

On July 16, 1945, the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis, commanded by Captain Charles McVay III, steamed out of San Francisco, Calif. Her top-secret cargo was the uranium core for the atomic bomb destined to be dropped—in early August—on Hiroshima, Japan.

The 13-year-old cruiser, once the flagship of the Fifth Fleet, completed the five thousand-mile journey to Tinian Island in 10 days. And, after unloading the main component of the bomb, she headed to Guam, which she reached the next day.

At 9 am, on Saturday, July 28, the Indianapolis departed Guam for Leyte Island in the Philippines. The cruiser was scheduled to arrive on the 31st.

I-58 Sees Its Target

The port director at Guam relayed the information to the port director at Tacloban, Leyte—along with orders to Rear Adm. Lynde McCormick aboard the battleship USS Idaho. The Idaho was instructed to join the Indianapolis for a gunnery-practice exercise. The message was received by the battleship; however, it was so garbled that it could not be deciphered. For some unknown reason, the Idaho’s communications officer did not request the message to be repeated. As a result, Admiral McCormick would not be looking to rendezvous with the cruiser.

The Indianapolis was not fitted with sonar to detect submarines. She would have to depend upon lookouts and radar to spot periscopes. Usually, the Indianapolis was escorted by ships equipped with sonar, but these vessels were not available at Guam at the time she sailed.

Captain McVay had instructions to zigzag in clear weather. But the night was overcast, and he did not order the evasive maneuver.

Meanwhile, through a sudden break in the clouds, the Japanese submarine I-58—captained by Commander Mochitsura Hashimoto—sighted the profile of the Indianapolis silhouetted in the moonlight.

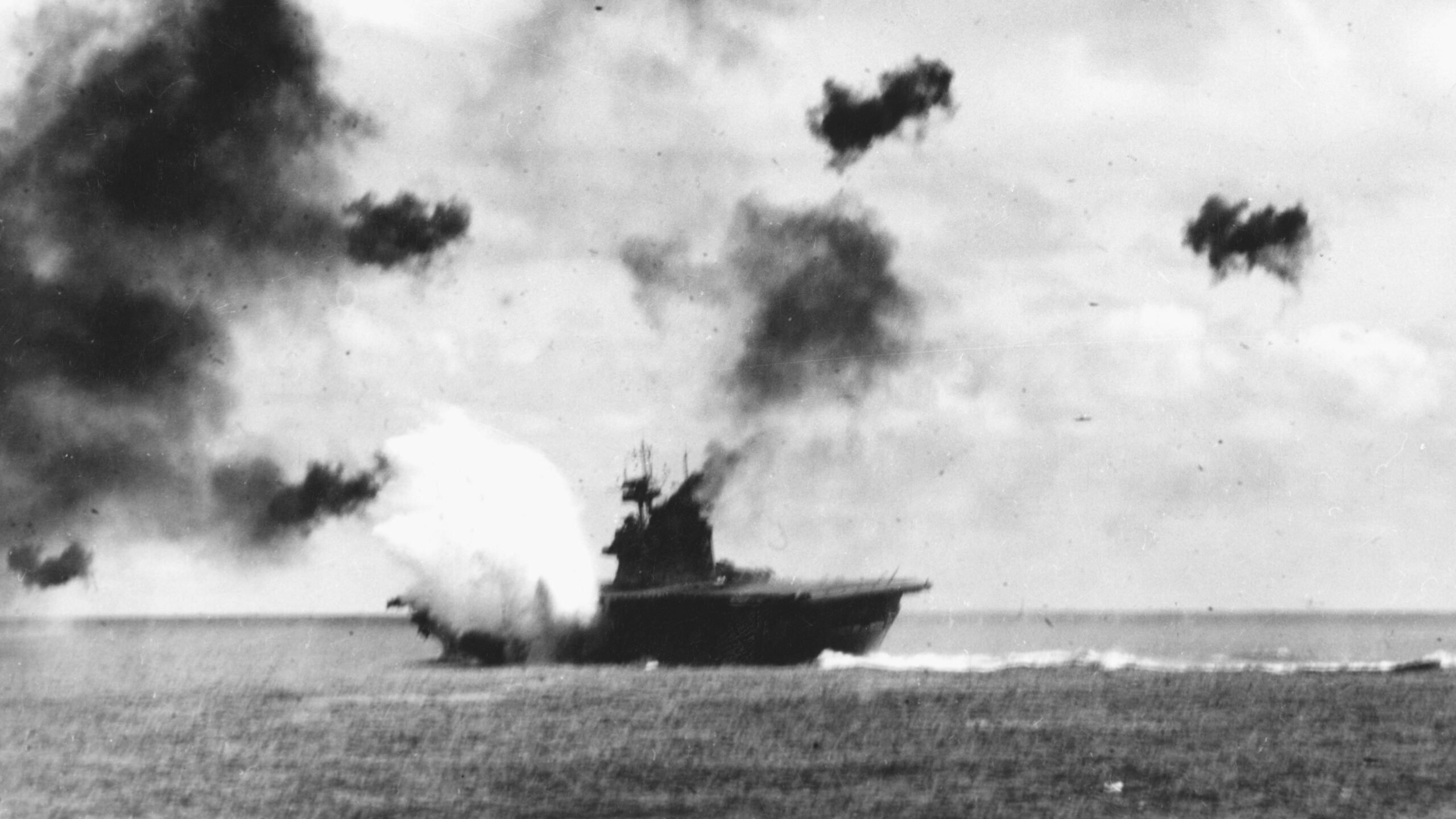

It was a few minutes after midnight, Sunday, July 30, when Hashimoto fired a spread of six torpedoes. The first smashed into the cruiser’s bow—ripping 40 feet clean off. A moment later, a second torpedo crashed amidships. All power and communications were immediately lost—not even an SOS could be sent out.

Tons of seawater flooded into the cruiser as at first she plowed forward without a bow. Then she began to list sharply to starboard. Orders were issued to abandon ship, but within only 12 minutes, the Indianapolis rolled over and sank.

A Watery Nightmare

An estimated four hundred men died in the torpedo explosions, but 850 men managed to escape to the sea. The cruiser went down so fast, however, that few lifeboats and rafts were put in the water. Most of the survivors depended on their life jackets to keep them afloat.

The terror began Monday—when the sharks attacked. But sharks were not the only danger to be faced. Because no other Allied craft were in the vicinity and no SOS had been sent, no Allied authorities would know for a considerable time about the sinking, thus delaying rescue efforts. The hours, then the days, wore on. Exposure to the blinding sun, vomiting from swallowing seawater and oil, extreme thirst and sheer desperation soon thinned the ranks of the survivors. Life jackets became waterlogged and lost their buoyancy, dragging sailors down to a watery grave.

The men in the water tried to attract the attention of distant aircraft, but for days to no avail. It was not until four days later that a Navy bomber pilot spotted the oil slick of the Indianapolis, and noticed dozens of delirious men frantically waving at him.

A Catalina PBY seaplane soon arrived and dropped life rafts and supplies. The pilot then landed on the water and 56 men climbed aboard—covering the body and wings. The PBY became a rescue boat.

A total of 316 sailors managed to survive the ordeal, roughly five hundred having survived the sinking but perishing in the water. Those who were plucked alive from the merciless ocean became members of a very select group—the USS Indianapolis Survivors Association. The U.S. Congress recognized the cruiser as a national memorial and, as with all lost ships, her status is “still at sea.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments