By Mason B. Webb

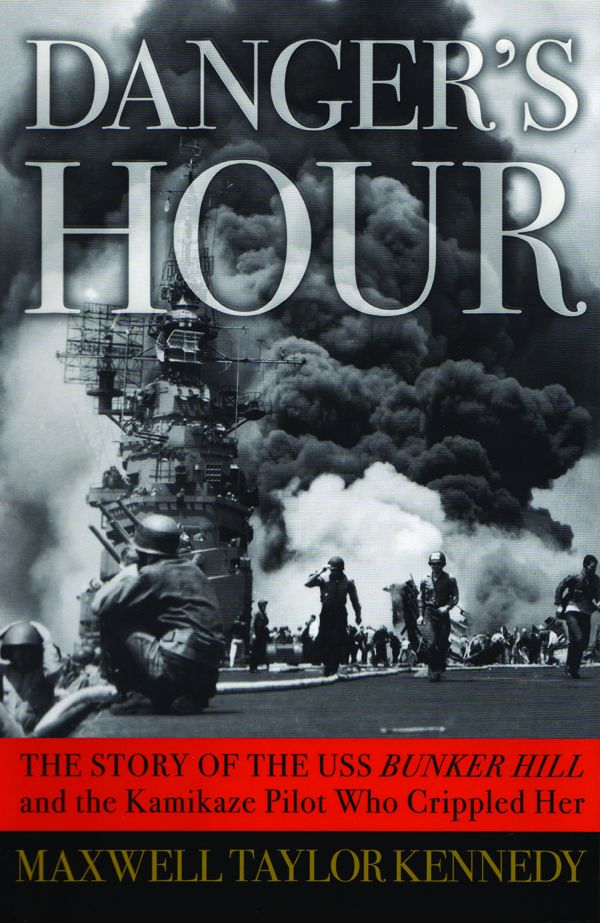

At exactly 9:58 am, on May 11, 1945, a Japanese kamikaze pilot named Kiyoshi Ogawa radioed his base 350 miles away that he had spotted the American fleet lying off the coast of Okinawa. With Ogawa was a formation of 18 dive-bombers, all of the other pilots either eager, or resigned, to die for the emperor in a suicide mission.

Pushing his plane into a steep dive, Ogawa aimed for an aircraft carrier––the base of the vital island structure in the center of the USS Bunker Hill, which held Admirals Marc Mitscher and Arleigh Burke. Ogawa’s last radio transmission was, “Now I am nose-diving into the ship.” Seconds later, tearing through a blizzard of heavy antiaircraft fire, he loosed his single bomb onto the flight deck and then he and his plane rammed at high speed into his target, killing himself and dozens of Americans aboard the ship. The carrier was instantly engulfed in smoke, flame, and flying debris.

Pushing his plane into a steep dive, Ogawa aimed for an aircraft carrier––the base of the vital island structure in the center of the USS Bunker Hill, which held Admirals Marc Mitscher and Arleigh Burke. Ogawa’s last radio transmission was, “Now I am nose-diving into the ship.” Seconds later, tearing through a blizzard of heavy antiaircraft fire, he loosed his single bomb onto the flight deck and then he and his plane rammed at high speed into his target, killing himself and dozens of Americans aboard the ship. The carrier was instantly engulfed in smoke, flame, and flying debris.

In Danger’s Hour: The Story of the USS Bunker Hill and the Kamikaze Pilot Who Crippled Her (Simon & Schuster, New York, 2008, 515 pp., photos, bibliography, index, hardcover, $30.00) author Maxwell T. Kennedy recounts the story of the kamikaze pilot and the stricken aircraft carrier.

Although badly damaged, the Bunker Hill stayed afloat and continued to battle the swarms of suicide planes with her antiaircraft weapons while other sailors worked to fight the fires and aid the wounded whose burned and mangled bodies were scattered everywhere.

In an act of extreme courage, the captain of the cruiser Wilkes-Barre pulled alongside the crippled carrier to assist in fighting the fires and bring aboard the injured.

For hours the Bunker Hill burned and threatened to explode, but still the rescue and firefighting efforts went on. Only through the unparalleled courage of hundreds of men at the risk of their lives was the Bunker Hill saved from sinking.

Yet the carnage was staggering. The kamikaze attack––the single most destructive suicide mission of the war––took 393 American lives and wounded more than 250 others.

In Danger’s Hour, drawing upon years of research and firsthand interviews with both American and Japanese survivors of the devastating aerial assault, Kennedy has crafted a superb, pulse-pounding account of the attack, the months that led up to it, and the tragic aftermath.

This is an absolutely stirring book that should be on every collector’s bookshelf.

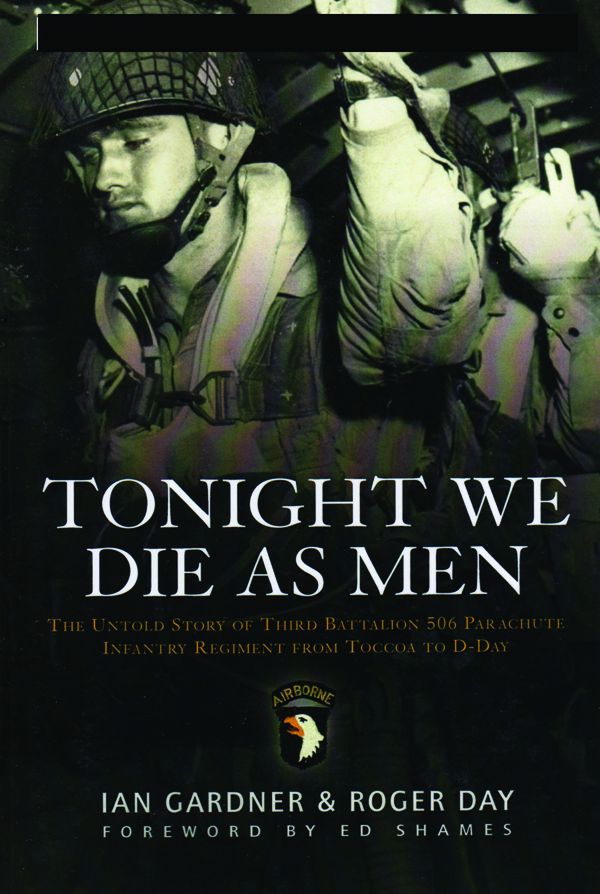

Tonight We Die As Men: The Untold Story of Third Battalion, 506 Parachute Infantry Regiment, from Toccoa to D-Day, by Ian Gardner and Roger Day, Osprey, Oxford, UK, 2008, 350 pp., photos, bibliography, index, hardcover, $27.95.

Tonight We Die As Men: The Untold Story of Third Battalion, 506 Parachute Infantry Regiment, from Toccoa to D-Day, by Ian Gardner and Roger Day, Osprey, Oxford, UK, 2008, 350 pp., photos, bibliography, index, hardcover, $27.95.

Taking their title from a brief prayer by 3rd Battalion commanding officer Lt. Col. Robert Lee Wolverton (who would be killed during the early morning hours of D-Day) said shortly before boarding a C-47 “Skytrain” aircraft for the flight to Normandy, Gardner and Day have produced a highly detailed study of one battalion’s harrowing first weeks fighting in France.

As Ed Shames, a veteran of the 506th, writes in the foreword, Tonight We Die As Men is “the most detailed history ever written about the battles that began the drive to free the European continent of the German armies…. Many books and accounts have been written about the invasion of Normandy, but never have you read one that has been more accurate about the facts and events of this period of warfare.”

The battalion’s D-Day objective was to land at Drop Zone D and seize control of two small wooden bridges––one for foot traffic and the other for vehicles––over the Douvre River east of Carentan. The mission was vital, for the Germans had built the bridges a few months earlier to enable them to rush reinforcements into the coastal area in the event of an Allied landing.

The fierce and costly battle for these two bridges is the focus of Tonight We Die As Men. The Germans, too, knew well the importance of the bridges and would not relinquish them without an all-out fight.

The two British authors take the reader back to Toccoa, Georgia, and the initial training received (some would say endured) by the men of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel Robert F. Sink, then on to airborne training at Fort Benning, Georgia, and Camp Mackall, North Carolina. They also flesh out the personalities mentioned in the book so that by the time the regiment is in England and preparing for its baptism of fire in Normandy the reader has developed a fondness for each trooper.

This personalizing of the men also serves to intensify the feeling of loss when the soldiers are killed in the savage fighting on D-Day and the month after. Of the 575 officers and men who jumped on D-Day, the 506th lost 93 killed and 73 listed as missing in action. Scores more were wounded.

It will be hard to find a better book about a single airborne battalion in World War II than this one.

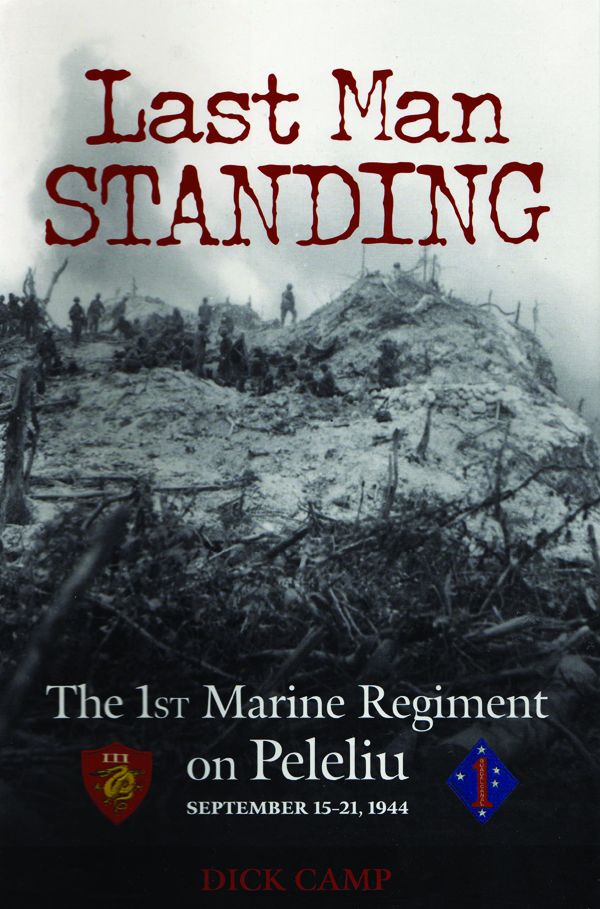

Last Man Standing: The 1st Marine Regiment on Peleliu, September 15-21, 1944, by Dick Camp, Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2008, 308 pp., photos, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $28.00.

Last Man Standing: The 1st Marine Regiment on Peleliu, September 15-21, 1944, by Dick Camp, Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2008, 308 pp., photos, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $28.00.

During six days on the small tropical island known as Peleliu in the Palau group, one of the bloodiest, most hard-fought, and controversial battles in U.S. Marine Corps history took place.

At the time, the American invasion and subsequent battle seemed like a necessary evil. In early 1944, American military planners and intelligence experts believed that the airfields and other facilities the Japanese had built on Peleliu and the neighboring islands posed a serious threat to General Douglas MacArthur’s promised return to liberate the Philippines.

Thus, as the American sweep westward across the Pacific gathered momentum the decision was made to neutralize Peleliu in an operation dubbed “Stalemate.” The 1st Marine Regiment, a component of the 1st Marine Division, was one of the American units selected to make the invasion, and Last Man Standing is the gripping story of their heroic and expensive assault.

In the intervening years since the battle’s end, many historians and strategists have declared that Peleliu was not worth the blood and treasure expended to take it––that it could have been bypassed and its defenders left to wither on the vine. Yet, the 17,000 Marines (and 11,000 soldiers of the Army’s 81st Infantry Division) crawling through the sand and unrelenting enemy fire had no such option. Their orders were to take the island no matter what the cost––just as the 11,000 Japanese defenders had orders to hold the island, even if all of them must perish in the process.

Working closely with two of the regiment’s battalion commanders and drawing upon additional interviews, extensive oral histories, and a treasure trove of photographs from the USMC History Division, retired Marine Corps colonel and military historian Dick Camp recreates the ferocious tempo of the battle as it was experienced by the men and their officers.

Here is the story of the legendary “Chesty” Puller leading his decimated regiment against fortifications manned by fanatical enemy soldiers who refused to surrender and who wanted only to take as many Americans with them as possible before they died.

Here also are the stories of a U.S. Marine Corps general refusing Army reinforcements, of a badly wounded battalion commander refusing evacuation while his men were still under fire, of men clinging to their positions by their fingernails in the face of certain death, knowing that only by superhuman effort could defeat be averted.

Most of all, Camp’s work is a richly detailed, deeply moving story of desperate combat and of valor among comrades joined against impossible odds.

This is truly a book that won’t soon be forgotten.

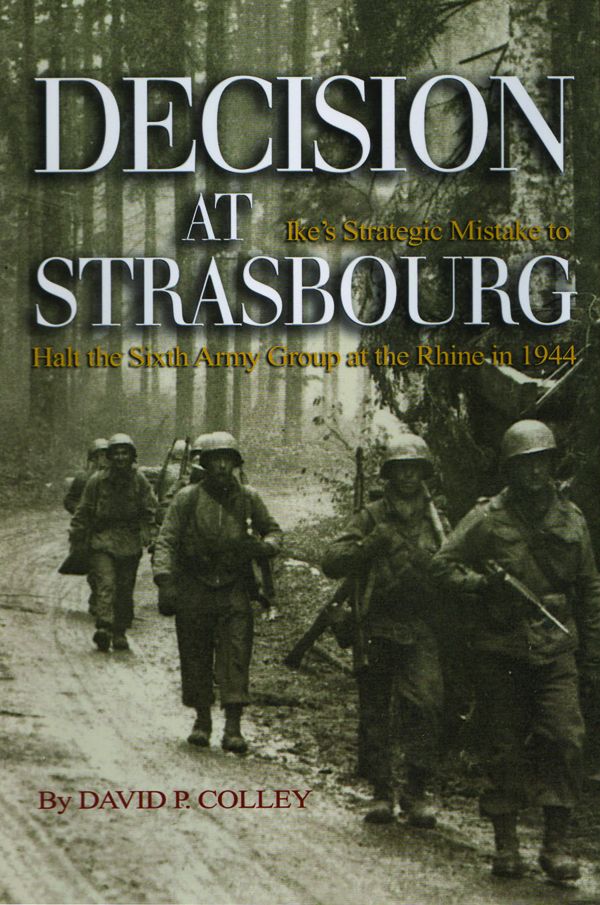

Decision at Strasbourg: Ike’s Strategic Mistake to Halt the Sixth Army Group at the Rhine in 1944, by David P. Colley, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2008, 251 pp., photos, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $34.95.

Decision at Strasbourg: Ike’s Strategic Mistake to Halt the Sixth Army Group at the Rhine in 1944, by David P. Colley, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2008, 251 pp., photos, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $34.95.

In late November 1944, just a day before Lt. Gen. Jacob Devers’s Sixth Army Group was scheduled to launch a bold attack across the Rhine River into Germany, General Dwight Eisenhower called a halt to the operation––a puzzling decision.

The U.S. Seventh Army and French First Army, both of which comprised Devers’ Sixth Army Group moving northward from the French Riviera following the Operation Dragoon landings there in August 1944, were poised at the banks of the Rhine near Strasbourg––the first Allied force to reach the swiftly flowing river that divides Germany and France.

Cross-river patrols discovered the fact that the opposite bank was nearly devoid of German troops and the situation was ripe for exploitation. Yet, inexplicably, Eisenhower told Devers to stand down.

At the moment the order to halt was issued, Lt. Gen. George Patton’s Third Army was heavily engaged against German forces in the Lorraine region. Had Devers been allowed to proceed with his assault, many historians believe, the Germans fighting Patton would have been dislodged and Patton could have driven into Germany––and perhaps have shortened the war by six months.

Until now, few have ever heard about this lost opportunity, nor have historians fully explained why Ike stopped Devers or conjectured on what the possible outcome of such an attack might have been.

As one of Ike’s possible motives for canceling the crossing Colley points to a personality clash between the supreme commander and Devers. Eisenhower disliked Devers and had little confidence that the attack, under Devers’ leadership, could succeed.

Colley, basing his book on the opinions of several high-ranking generals, including Patton, is not shy about offering his view that Devers’ attack would have been a bold and likely successful maneuver that could have dramatically shortened the war and saved thousands of American lives. As events turned out, the Allies did not cross the Rhine until March 1945, five months later.

This is an intriguing “what if” book that explores questions that have gone unanswered for more than six decades. Not to be missed.

Fighting for Hope: African American Troops of the 93rd Infantry Division in World War II and Postwar America, by Robert F. Jefferson, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, 2008, 321 pp., photos, bibliography, index, hardcover, $55.00.

Fighting for Hope: African American Troops of the 93rd Infantry Division in World War II and Postwar America, by Robert F. Jefferson, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, 2008, 321 pp., photos, bibliography, index, hardcover, $55.00.

That the United States discriminated against black soldiers, sailors, and airmen during World War II is well known. Even at a time when America was fighting to defeat the Nazi regime which espoused racial and ethnic hatred, the U.S. military was engaged in maintaining the nation’s status quo of “Jim Crow” segregation.

Black (then called Negro or colored) officers were forbidden from using whites-only officers’ clubs. Black troops were not integrated into white units. Black sailors could serve aboard U.S. Navy ships, but only in lowly capacities, such as mess stewards. Black airmen flew in black-only squadrons. Most blacks who enlisted or were drafted served only as “service” personnel, such as truck drivers and stevedores.

It was widely believed by the white establishment at the time that black warriors could never be as courageous or as hard-fighting as their white counterparts. It was only when President Harry Truman integrated the armed forces in 1947 that the wall of American apartheid began to be torn down.

Yet, the record shows that blacks, when given a chance, could be every bit as good––if not better––than their white comrades in arms. For example, Dorrie Miller, a black mess steward aboard the battleship USS West Virginia, manned a machine gun during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and, at the risk to his own life, carried his mortally wounded commander to a place of safety. The Tuskegee Airmen, a group of all-black aviators, proved with their sterling combat record that they were equal to white American pilots and even better than the Germans.

Now comes a fascinating history that shows how African-American military men and women seized their dignity through barracks culture and community politics during and after World War II. Drawing on oral testimony, unpublished correspondence, archival records, memoirs, and diaries, author Robert F. Jefferson, an associate professor of history at Xavier University in Cincinnati, explores the curious contradiction of war effort idealism and entrenched discrimination through the experiences of the 93rd Infantry Division.

Led by white officers, and with presumed substandard fighting abilities, the division was largely relegated to support roles during the advance on the Philippines, seeing action only later in the war when U.S. officials found it unavoidable.

Jefferson discusses racial policy within the War Department, examines the lives and morale of black GIs and their families, documents the debate over the deployment of black troops, and focuses on how the soldiers’ wartime experiences reshaped their perspectives on race and citizenship in America. He finds in these men and their families incredible resilience in the face of racism at war and at home and shows how their hopes for the future provided a blueprint for America’s postwar civil rights struggles.

Integrating both social history and civil rights movement studies, Fighting for Hope examines the ways in which political meaning and identity were reflected in the aspirations of these black GIs and their role in transforming the face of America.

An important and timely book, especially given the recent historic changes in the American political scene.

A Foot Soldier for Patton: The Story of a “Red Diamond” Infantryman with the US Third Army, by Michael C. Bilder with James G. Bilder, Casemate, Philadelphia, 2008, 294 pp., photos, hardcover, $32.95.

A Foot Soldier for Patton: The Story of a “Red Diamond” Infantryman with the US Third Army, by Michael C. Bilder with James G. Bilder, Casemate, Philadelphia, 2008, 294 pp., photos, hardcover, $32.95.

One of many remarkable recent memoirs, A Foot Soldier for Patton takes the reader along on a harrowing journey from the hedgerows of Normandy beginning in July 1944, until the final collapse of Nazi Germany in May 1945, when Third Army and the 5th Infantry Division had pushed all the way into Czechoslovakia.

Michael Bilder, who had emigrated to the U.S. from Germany before the war, took part in all five of Third Army’s major campaigns across the continent, sometimes even acting as interpreter for American officers interrogating German POWs.

Bilder, assisted by his son James in a true labor of love, has put together a startlingly frank, often humorous, and deeply penetrating look at combat and army life from an ordinary GI’s point of view. For example, Bilder recounts a couple of incidents at Caumont, in Normandy, where the 5th was engaged in heavy fighting. “I saw one officer who wore hand grenades on his hips like six shooters. While we were fighting in the hedgerows, a piece of shrapnel from a German grenade hit one of the grenades he was wearing and detonated. As he lay dying, all he said over and over again was, ‘What’s gonna happen to my men?’

“At the other extreme, we saw an officer confiscate a German motorcycle we had just captured so that it could be used to deliver messages. That was reasonable enough, but before turning it over to headquarters, he decided to take a joy ride in a combat zone. We found his body near the German lines. He had been shot and picked clean of valuables, right down to his Notre Dame ring.”

Later, during a firefight in August 1944, Bilder was tossing grenades at a group of enemy soldiers while the rest of his squad was advancing toward the foe. He writes, “I must have been overly anxious because one of our guys yelled out, ‘Bilder, hold those grenades longer! The krauts are throwing them back!’”

A Foot Soldier for Patton is filled with these kinds of vignettes and personal remembrances, the kind that only the best memoirs can deliver.

Short Bursts

Merchant Mariners at War: An Oral History of World War II, by George J. Billy and Christine M. Billy, University Press of Florida, Gainesville, 2008, 322 pp., photos, bibliography, index, hardcover, $30.00.

Merchant Mariners at War: An Oral History of World War II, by George J. Billy and Christine M. Billy, University Press of Florida, Gainesville, 2008, 322 pp., photos, bibliography, index, hardcover, $30.00.

The Allies could not have won World War II without the lifeline of supplies that gave Great Britain, the Soviet Union and, after America’s entry into the war and deployment overseas, the U.S. all the tanks, trucks, food, fuel, ammunition, and other vital equipment needed to defeat the Axis powers. Yet, the story of the Merchant Marine is a story that has largely gone unnoticed, under-reported, and under-appreciated (see the article about the Merchant Marine in WWII History, January 2007 edition).

Naval history has almost exclusively centered around the combat vessels––the battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and aircraft carriers. Yet, the thousands of cargo ships that plied the dangerous waters in which lurked enemy submarines were manned by courageous sailors who braved blockades, torpedoes, bombings, and horrendous weather and sea conditions to deliver the essential goods.

Going a long way to rectify the problem of this branch of service’s invisibility is Merchant Mariners at War, an excellent chronicle by a husband and wife team of experts. George J. Billy is the chief librarian at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy and his wife Christine was the assistant to the public information officer at the Academy. They know of what they write.

Deftly combining official records and oral histories by 59 Merchant Marine Academy graduates who served in World War II, the authors have crafted a fine portrait of the men and ships who made victory possible.

The stories of privation, hardship, and heroism captured in this book will go a long way in convincing readers of the vital role played by this neglected branch of service.

When Baseball Went to War, edited by Todd Anton and Bill Nowlin, Triumph Books, Chicago, 2008, 244 pp., photos, audio CD, hardcover, $27.95.

When Baseball Went to War, edited by Todd Anton and Bill Nowlin, Triumph Books, Chicago, 2008, 244 pp., photos, audio CD, hardcover, $27.95.

Unlike many of the pampered athletes of today, yesterday’s sports heroes realized that the true definition of heroism was not hitting a homer un in the bottom of the ninth, but putting one’s life on the line when one’s country is in peril.

One day after Japanese bombs fell on Pearl Harbor, the Cleveland Indians’ star pitcher Bob Feller enlisted in the U.S. Navy and volunteered for combat duty. He was the first major leaguer to do so, but would not be the last. Hundreds of other professional players soon followed Feller’s lead and traded their baseball uniforms for Army, Navy, Marine, and Air Corps uniforms.

Anton and Nowlin have collected a sparkling series of essays and scores of revealing photographs to chronicle the battlefield exploits of famous ballplayers, many of whom went on to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Included in this outstanding work are brief wartime bios of such diamond luminaries as Feller, Joe DiMaggio, Warren Spahn, Ted Williams, Yogi Berra, Jerry Coleman, Johnny Pesky, and many others. Also included is a complete listing of all of the major leaguers who served in World War II, and a roll of honor of major and minor league ballplayers who were killed during the war.

When Baseball Went to War is the perfect book for the military buff and baseball fan.

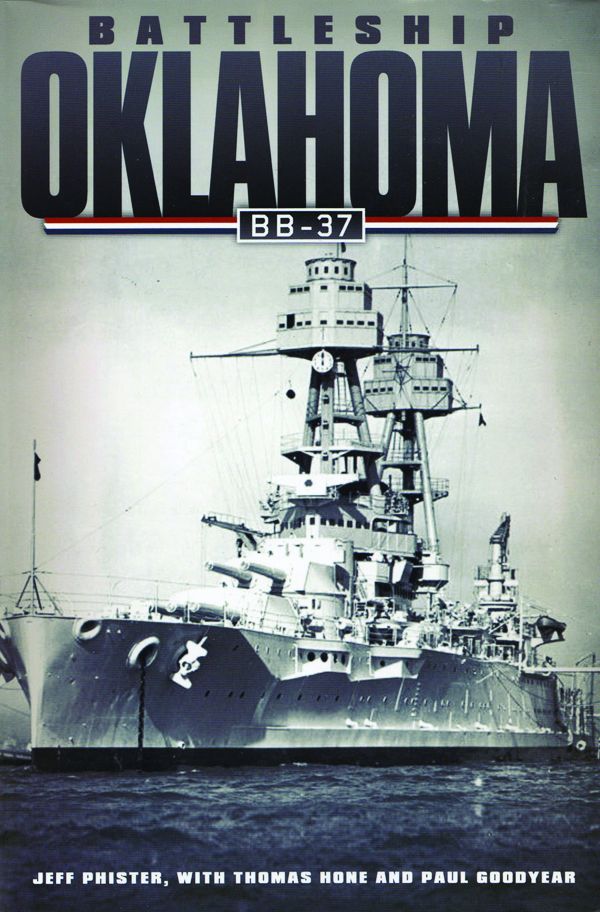

Battleship Oklahoma, by Jeff Phister, with Thomas Hone and Paul Goodyear, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2008, 256 pp., photos, bibliography, index, soft cover, $19.95.

Battleship Oklahoma, by Jeff Phister, with Thomas Hone and Paul Goodyear, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2008, 256 pp., photos, bibliography, index, soft cover, $19.95.

Launched in March 1914, the battleship USS Oklahoma (BB-37) is probably the most famous American warship never to have fired a shot in anger.

Deployed too late to take part in World War I, it was sunk during the opening minutes of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Much of the book deals with the frantic efforts made by her valiant crew during and in the minutes immediately following the attack to rescue trapped and wounded shipmates and prevent the ship from sinking.

In one passage describing efforts to reach men caught in nearly flooded compartments days after the attack, Phister writes, “Believing the rescuers were still in the vicinity, [Carpenter’s Mate Walter F.] Staff decided to try to access the linen compartment again. Moving sideways to the bulkhead, he reached below the water and pushed. Whatever had wedged it shut before was gone because it opened with relative ease. He knew the linen compartment was wider than the one they were in, so he assumed there would be a larger pocket of air on the high side. Positioning himself in front of the opening, he told [Jackson P.] Centers to follow him. They both entered, sealing the hatch behind them. A short time later, they heard voices. They had not been abandoned.”

The book contains many more accounts of bravery and heroism above and beyond the call of duty, and is a fitting tribute to a valiant but doomed ship manned by a proud crew. Highly recommended.

Armored Thunderbolt: the U.S. Army Sherman in World War II, by Steven Zaloga, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2008, 360 pp., photos, bibliography, index, hardcover, $34.95.

Armored Thunderbolt: the U.S. Army Sherman in World War II, by Steven Zaloga, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2008, 360 pp., photos, bibliography, index, hardcover, $34.95.

The M4 Sherman tank was arguably the most famous of all the World War II tanks. Although not the toughest in terms of armor protection or firepower, it helped the Allies win the war just by its sheer numbers (nearly 50,000 were built from 1942 to 1946) and its relatively easy repairability and rugged reliability that kept it going even while the enemy’s tanks were breaking down.

Numerous books have been published about the Sherman, but Steve Zaloga’s richly illustrated volume is packed with a comprehensive text and hundreds of detailed, never before seen photos found in few, if any, other histories of the famed tank.

The author closes with the postwar role played by Shermans in armies all over the world and includes several appendices that show technical drawings, chart technical and production data, and provide strength and loss statistics. All in all, one can truly call this book, “Everything you ever wanted to know about the Sherman tank.”

As Zalonga makes clear, the Sherman may not have been the best tank of World War II, especially in head to head engagements with foes like the German Panther and Tiger, but the combination of sound design, innovative tactics, well trained crews, mechanical reliability, and mass production made the Sherman a war winner.

Highly recommended for anyone with even the slightest interest in armored warfare in general and this American original in particular.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments