By Michael D. Hull

One night in mid-October 1941, a British Army intelligence officer disguised as a Senussi Arab was dropped by parachute behind the German lines in the Italian colony of Libya.

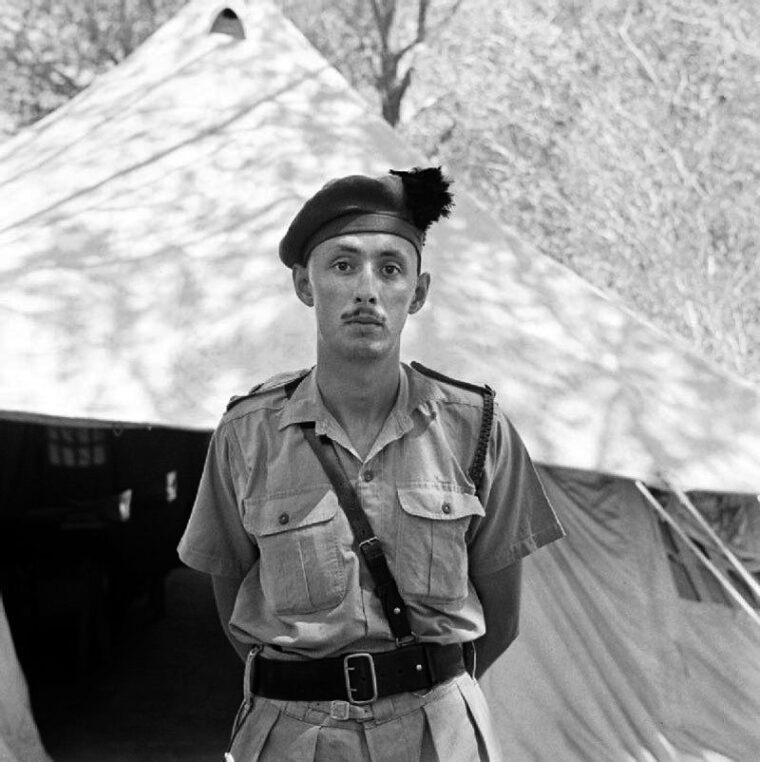

He was Captain John E. “Jock” Haselden of the famed Long-Range Desert Group (LRDG), a specialized British force led by Lt. Col. David Stirling that conducted reconnaissance patrols and hit-and-run raids against enemy installations in North Africa. Bearded and weather beaten, Haselden wore tattered Arab robes and carried a staff while venturing out alone on his intelligence-gathering forays. Born and raised in Egypt and a former Cairo cotton broker, he was fluent in Arabic.

His mission on this particular night was a hazardous one—to locate the headquarters of the commander of the German forces in North Africa, the legendary General Erwin Rommel. Haselden was to lay the groundwork for a bold attempt—tied to a major offensive by the British Eighth Army—to either capture or kill Rommel and his cantankerous Italian field commander, General Ettore Bastico. For several months, Rommel had proved to be a skillful and formidable foe by outwitting and outmaneuvering the British during the seesawing Western Desert campaigns.

Based on radio intercepts of German message traffic, “Sigint” (Signals Intelligence) at the British Middle Eastern Command headquarters in Cairo had come to the conclusion that a remote village named Beda Littoria in the northern Libyan hump was the probable site of Rommel’s headquarters.

After burying his parachute in the sand, Captain Haselden trudged to the outskirts of the dusty village a dozen miles south of the Mediterranean coast, west of Derna and not far from the site of the ancient city of Cyrene, the birthplace of Hannibal, to verify the Sigint information. Stealthily, he trained his field glasses on stuccoed Italian colonial buildings clustered in olive and cypress groves and groups of German troops.

Off to one side, Haselden could see a villa and an official building that the Italians called the Prefettura. Parked around it were about 20 Afrika Korps communications trucks, while a steady stream of vehicles disgorged and retrieved officers and dispatch riders. The British officer gasped when he spotted General Rommel striding out of the Prefettura and driving off in a command car. Haselden had hit the jackpot; apparently Beda Littoria was indeed the headquarters of the “Desert Fox.”

Haselden hastily stole away into the desert and linked up with a LRDG patrol two days later. He was whisked back to Cairo with his information, and plans and preparations were drawn up. By mounting a raid on Rommel’s headquarters, the British hoped to wreak chaos in the command system of the Afrika Korps and its Italian allies. The operation was likely to prove one of the most daring special force missions of World War II.

The British Commandos assigned to carry out the mission had come to the Mediterranean theater as part of the “Layforce” contingent led by Lt. Col. Robert E. “Lucky” Laycock, commander of Commando operations and the elite Special Boat Section there. One of his units was the 11th (Scottish) Commando, which had practiced night landings from submarines using rubber dinghies and lightweight canvas canoes called folbots.

The idea for the raid on Rommel’s headquarters 250 miles behind enemy lines had been formulated in the autumn of 1941 by temporary Lt. Col. Geoffrey Charles Tasker Keyes of the 11th Commando, the 24-year-old son of Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Keyes. A decorated hero of the Boxer Rebellion and the Zeebrugge and Dover naval actions in World War I, Sir Roger had been chosen by Prime Minister Winston Churchill to direct all Commando operations from Lord Louis Mountbatten’s Combined Operations headquarters.

A brave, competent officer and the youngest lieutenant colonel in the British Army, Keyes led the planning for the upcoming raid—code named Operation Flipper—and insisted on leading it personally. Simultaneous actions to support the November 16-17 British offensive codenamed Operation Crusader were to be undertaken by the LRDG and the Special Air Service. The initial objectives of the Laycock-Keyes force were to attack the Italian forces’ headquarters at Cyrene and destroy telephone and telegraph services; hit the Italian intelligence center at Appollonia; cut communication lines around El Faida, and assault the Afrika Korps headquarters at Beda Littoria and Rommel’s villa west of the village.

Colonel Laycock, himself a gallant veteran of special operations in Libya, Rhodes, and Crete who would later win the Distinguished Service Order and lead Commandos and U.S. Rangers in the invasion of Salerno, voiced reservations about the planned mission. A London-born former subaltern in the Royal Horse Guards, he reported, “I gave it my considered opinion that the chances of being evacuated after the operation were very slender, and that the attack on General Rommel’s house in particular appeared to be desperate in the extreme. This attack, even if initially successful, meant almost certain death for those who took part in it. I made these comments in the presence of Colonel Keyes, who begged me not to repeat them lest the operation be canceled.”

Laycock tried several times to persuade Keyes to detail a more junior officer to lead the raid, but he refused. “On each occasion,” said Laycock, “he flatly declined to consider these suggestions, saying that, as commander of his detachment, it was his privilege to lead his men into any danger that might be encountered—an answer which I consider [was] inspired by the highest traditions of the British Army…. Colonel Keyes’s outstanding bravery was not that of the unimaginative bravado who may be capable of spectacular action in moments of excitement, but that far more admirable calculated daring of one who knew only too well the odds against him.” Despite his misgivings, Laycock agreed to accompany the raiding force as an observer.

On the night of Thursday-Friday, November 13-14, 1941, after a three-day voyage from Alexandria, two 1,575-ton Royal Navy submarines, HMS Torbay and HMS Talisman, carrying 60 Commandos, stood off the coast of Djebel Akhdar, 20 miles west of Appollonia, Libya. Periscope observations were made of the planned landing area. From a small cove on the shore, Captain Haselden, who had been designated to guide the raiders to Rommel’s headquarters, sent a prearranged signal out to the submarines. As soon as his blinking lights were spotted, the vessels flashed back a recognition signal.

But things began to go wrong from the start. The Commandos had been trained to disembark from submarines in calm waters, but a gale was howling on the Libyan coast that night. Rough seas hampered the operation. Instead of the estimated 90 minutes, it took seven hours to get 28 men and Colonel Keyes, the operational commander, ashore from the slippery deck of the first submarine, the Torbay.

When the Talisman neared the shore to disembark her Commandos, she touched bottom. In the resulting turmoil, seven landing boats with 11 men were swept overboard. Several were never seen again. A few men managed to scramble ashore, but the Talisman withdrew with many members of the raiding force still aboard.

Early in the morning of November 14, Keyes assembled his men in Haselden’s cove, a dozen miles from Beda Littoria. All were wet, chilled to the bone, and critically short of vital weapons and equipment. The little force was considerably understrength for its mission. Keyes was furnished with directions and an Arab shepherd as his guide, while Haselden slipped away to get ready for the second part of his assignment—to blow up a German communications outpost on the same night that Keyes’s team hit Rommel’s headquarters.

Colonel Laycock, meanwhile, decreed that under the circumstances the Commandos’ objectives must be curtailed. It was agreed that only two of the four planned attacks would be undertaken—on the communications systems at Cyrene and the German headquarters at Beda Littoria. The plan to hit Rommel’s villa was dropped.

Laycock stayed at the landing site to coordinate operations while Keyes, Captain Robin Campbell, his second in command, and the 28 Commandos set off at nightfall on November 15 for a grueling trek to their objectives. Rain poured for 48 hours, and the raiders were soaked as they splashed through ankle-deep mud, slipped on greasy rocks, and picked their way over rock-strewn sheep tracks and a 1,800-foot ridge in the darkness. Their Arab guide refused to go farther as the weather deteriorated, and morale began to flag. But Keyes’s stolid resolve kept his men moving forward. By the night of November 16, the column had reached a small cave about five miles from Beda Littoria.

The Commandos spent the rest of the night and most of the following day there. Keyes stayed on the beach through the night to meet any men who might have managed to get ashore from the second submarine. The hideout was odorous and uncomfortable, but the raiders found shelter from the torrential rain and cold that had plagued them almost continually since coming ashore. They lit a fire to warm themselves and dry their clothing, cleaned their Sten submachine guns and .38-caliber pistols, and groused about the absence of the blazing sunshine that reputedly bathed the southern Mediterranean shore.

On the afternoon of November 17, Colonel Keyes made a short reconnaissance foray then briefed his men at 6 pm. He divided his small force in two, sending one half off to detonate a communications pylon near Cyrene while the rest listened to his detailed plan for the assault on Rommel’s headquarters. Then, with blackened faces and wearing plimsolls (sneakers), they set off on the final stage of their mission.

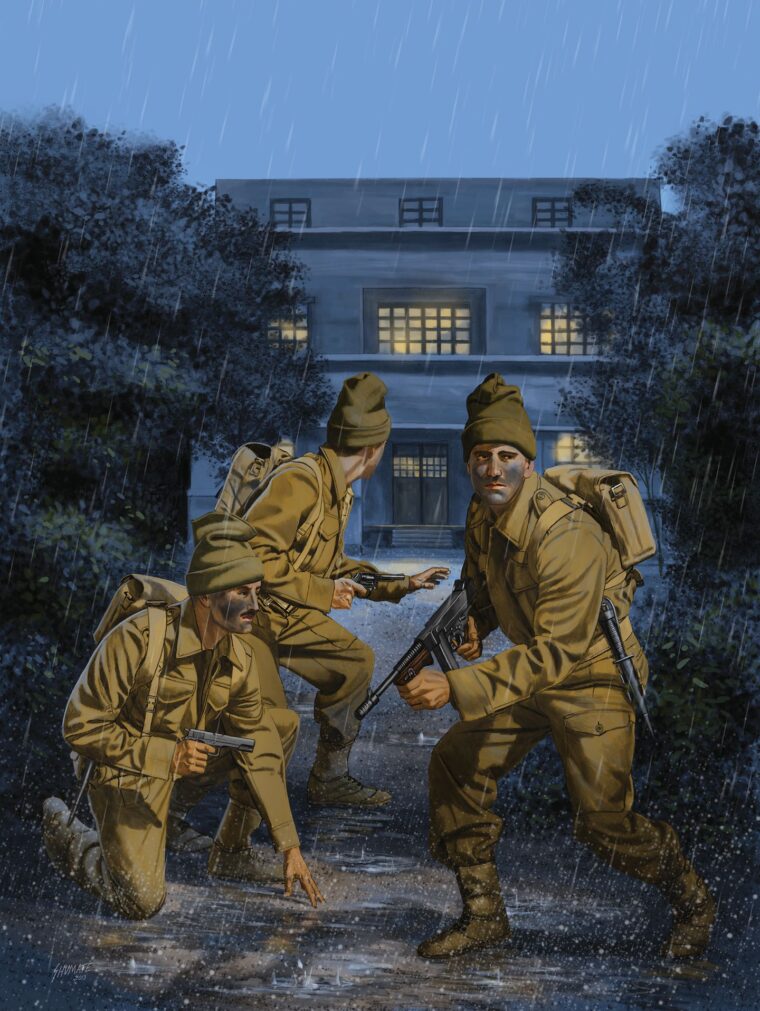

The raiders bided their time during the waning daylight hours and moved forward in darkness to a ridge just above Beda Littoria. Pushing on, they reached the outskirts of the village around midnight and crept forward stealthily toward the German headquarters in the Preffetura, an austere, two-story building standing away from the main village. Keyes and Sergeant Terry were in the lead, about 50 yards ahead.

Suddenly, one of the Commandos tripped over a tin can, setting off frenzied barking from neighborhood dogs and a scream from an Arab villager. When two Italian soldiers emerged from a hut to investigate, the quick-thinking Captain Campbell shouted to them in fluent German that they were an Afrika Korps patrol. The disgruntled Italians went back into their hut.

By this time, Colonel Keyes had cut through the wire surrounding the headquarters building. The rain that had hampered his men now yielded a dividend, confining the enemy sentries to their tents, except one. Keyes dispatched him quietly with his fighting knife, and the rest of the force joined him, carrying enough explosives to wreck both the Prefettura and a nearby power plant.

With a covering party blocking the approaches to the building and guarding the exits from neighboring structures, Keyes, Campbell, Sergeant Terry, and three other ranks crept forward through the security fence. But the mission was about to turn into a fiasco. Keyes, Campbell, and Terry planned to sneak into the Nazi headquarters. Keyes hoped to climb through a window or find a back door but a quick investigation revealed no easy access. So the raiders took the bull by the horns.

Captain Campbell pounded on the front door and demanded entry in his fluent German. When a sentry eventually opened the door, Keyes jammed his revolver in the startled soldier’s ribs. But the brave, well-trained German grabbed the muzzle and backed Keyes against a wall. The colonel struggled to draw his knife while the enemy soldier shouted an alarm. The element of surprise was lost. Campbell shot the struggling German over Keyes’s shoulder, and the colonel flung the door open.

The six British raiders dashed inside, and the next few minutes brought a chaos of Sten-gun and pistol fire, shouts of anguish and alarm, slamming doors, and running feet on stone steps. A duty officer had aroused sleeping Germans. A man came clattering down the stairs, but Sergeant Terry chased him off with a burst from his Sten gun.

The raiders checked one of many rooms off the main hall and found it empty. Then a door on the left side of the hall started to open. A light shone inside, and the Commandos could hear the occupants moving about. Keyes kicked the door open wide to see about 10 Germans in helmets frozen in shock. After the colonel emptied his Colt .45 automatic pistol into the room, Campbell appeared at his elbow and said he would toss a hand grenade in. Keyes shut the door while Campbell pulled the pin, reopened it, and the grenade and a burst of Sten-gun fire went in.

The grenade exploded with a loud crash, but some of the surviving Germans fired back at the raiders. A single shot hit Keyes just above the heart. Campbell and Terry quickly carried him outside, and he died within a few minutes. An eerie silence then fell upon the Prefettura and every light went out.

Captain Campbell stole back into the house to check for further signs of enemy activity and then ran around to the rear of the building where the covering party had been left. The Commandos were there, crouching in the darkness, but they heard no password and thought that Campbell was a German. A Sten gun round smashed his shin bone. He ordered his men to withdraw and leave him behind. The raiding party was left without an officer.

Sergeant Terry took over. He brought up enough explosives to demolish the Prefettura but discovered that the fuses were rain-soaked and unusable. The only damage that the raiders could inflict now was by dropping a grenade down the breather pipe and blowing up the main generator and by destroying some Afrika Korps vehicles. Terry and the other survivors then withdrew, hoping that the enemy would tend their wounded. Several Commandos had been captured by Germans alerted to their assault.

By the following evening of November 18, the 22 survivors reached Colonel Laycock at the shore. Then followed several frustrating hours while their signals to HMS Torbay—surfaced 400 yards out—were unacknowledged. Belated return signals to the exhausted Commandos were incomprehensible, and no boats came in to fetch them. So, just before dawn the following morning, Laycock and the survivors filed into a wadi to lay low for the day and plan how to get to the British lines. But hostile Arabs and then Italian troops attacked them. Laycock ordered the men to split into small groups and disperse before an inevitable and more serious assault came from the Germans.

All of the Commandos except two were eventually seized by the Germans or shot by Arabs. Colonel Campbell was carried off to a German prison camp, where he was well treated but had to have his shattered leg amputated.

at Beda Littoria in Libya just as their doomed mission is getting underway.

Colonel Laycock and Sergeant Terry managed to get clear of the wadi and spent 41 wearying days trekking across the desert toward the Eighth Army lines. They were given food by friendly Senussi tribesmen, and water was not a problem because it rained almost every day. They reached the British lines on Christmas Day. Captain Haselden also managed to get away from the wadi and linked up with an LRDG patrol. After a rest, Laycock was flown back to England to take command of the Special Service Brigade. The intrepid Haselden, who had been promoted to lieutenant colonel, was killed in a raid on Tobruk in September 1942.

Operation Crusader, the big offensive by Lt. Gen. Sir Alan Cunningham’s Eighth Army for which the Keyes raid was a diversion, had meanwhile got underway. One hundred thousand men, more than 700 Cruiser and Matilda tanks, and 5,000 artillery units, armored cars, trucks, and personnel carriers rolled forward during the weekend of November 16-17.

A masterpiece of deception, Crusader was a wide-scale armored sweep toward besieged Tobruk from the south while British Commonwealth infantry forces pinned down Axis positions on the Libya-Egypt frontier. The Afrika Korps and its Italian allies were driven back to Benghazi with severe losses, and the British kept up the pressure through December.

Rommel was forced to abandon Cyrenaica, the eastern province of Libya, and fall back to defensive positions at El Agheila. But the Desert Fox quickly recovered. The gallant General Cunningham, who had defeated the Italians in Ethiopia but who lacked a grasp of armored warfare, suffered a nervous breakdown. He was soon replaced by the vigorous, self-confident Lt. Gen. Sir Neil Ritchie. From Operation Crusader until the climactic Battle of El Alamein in October 1942, the desert war continued to rage back and forth.

While it was a daring operation carried out with heroism, the raid on Rommel’s headquarters had turned into a costly and unnecessary disaster. British intelligence was correct that the Prefettura in Beda Littoria had been used by the general, but only briefly. It was only by chance that Captain Haselden had spotted him there; Rommel was making a routine visit to the Afrika Korps quartermaster general’s staff, which had taken over the building.

The Desert Fox had long since shifted his lair to a location much closer to the front lines. In fact, and unknown at the British intelligence offices in Cairo, Rommel was not even in North Africa at the time of the raid. He had been flown to Rome two weeks before to rest and celebrate his 50th birthday.

Toward the British raiders who had sought to capture or kill him, Rommel reacted with characteristic chivalry. He defied Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler’s newly issued directive ordering the immediate execution of captured Commandos and arranged for Colonel Keyes to be buried with full honors. The German general’s chaplain conducted the ceremony as Keyes was laid to rest beside four Afrika Korps soldiers killed in the raid. Rommel gave a funeral oration and, in an unprecedented soldierly gesture, pinned his own Iron Cross on the Briton’s body.

The young colonel was subsequently gazetted on June 19, 1942, and awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest decoration for valor. A memorial service in London’s Westminster Abbey was attended by some of the Commandos who had survived the doomed raid. Colonel Keyes’s remains were later reburied at the Eighth Army cemetery in Benghazi.

The raid served to point up flaws in the training and tactics of British Special Forces units. Eighteen months after the raising of the Commandos, and despite the fighting spirit displayed in Beda Littoria, there was still much to be learned. Inadequate planning and faulty intelligence were stressed as the Combined Operations chiefs critiqued the mission.

The Commandos learned their bitter lessons and went on to serve in many World War II campaigns as a peerless special force—mentoring the U.S. Rangers and setting an example for other elite assault units in the years to come.

Frequent contributor Michael D. Hull has written on numerous topics for WWII History. He resides in Enfield, Connecticut.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments