By Eric Niderost

In the summer of BC 481, a delegation from Athens arrived at Delphi in central Greece to consult with the oracle of Apollo. The Sanctuary was always crowded with people seeking advice from the god, or perhaps a glimpse into an uncertain future. The oracle was located in the temple of Apollo, a building perched on a slope that was reached by a winding Sacred Way. The Sacred Way was lined with splendid marble buildings, including treasuries where votive offerings and other objects of value were stored.

It was a magnificent display, mute but eloquent testimony to the shrine’s fame and influence, but the Athenians were in no mood for sightseeing. King Xerxes of Persia was making preparations to invade Greece; even now his forces were marshaling and a mighty armada was being assembled. Nine years earlier, the Athenians had defeated a Persian invasion force at Marathon sent by Xerxes’ father, Darius. It was a setback Xerxes was not likely to forgive, much less forget. It was clear Athens was going to be a special target of the Great King’s ire.

Apollo’s prophecies were given substance through a medium called the Pythia. Accounts differ slightly, but apparently she was seated on a tripod near the omphalos (navel), a stone that was said to mark the center of the world. Some say she chewed laurel leaves, others that she inhaled burning laudanum, or even breathed vapors issuing from a rock cleft. Whatever means were used, the Pythia fell into a trance, and while in the trance babbled incoherently. These ravings were messages from Apollo, and were duly recorded by nearby priests for translation.

A Grim Future for Greece

Aristonice the Pythia took her seat, separated from the Athenian petitioners by a veil. She soon fell into a stupor, then began raving in a voice that none could understand. The gibberish was carefully recorded, and when the message was translated it was far from comforting. “Leave your homes,” it began, “and fly to the ends of the earth.” The message continued that “all is lost,” and prophesied that “many shrines of the gods” would meet a “fiery destruction.”

The Athenians’ blood ran cold; here was a dire prediction of utter ruin. Stomachs knotted with anxiety, faces downcast, they left the temple in a state of deep depression. But one, Timon, a man who lived in Delphi and probably was attached to the Temple of Apollo in some way, told the Athenians to try again. If they returned with an olive branch, a token of supplication, maybe Apollo would reconsider his harsh words.

Is There any Hope?

They did as advised, and Aristonice delivered a second prophecy. It was the last lines that gained the most attention. “Wide-seeing Zeus grants to Athena, triton-born, that the wooden walls alone remain unbreached.… O divine Salamis! You shall destroy the children of women.…”

The second prophecy offered a glimmer of hope, but as usual the words were ambiguous and subject to interpretation. What, for example, were the “wooden walls”? The salvation of Athens, and Greece itself, might well rest on the right answer.

The Athenian leader Themistocles was to become a central figure in the debate over the interpretation of the prophecy. A leading proponent of naval power, Themistocles was certain the “wooden walls” meant a powerful Athenian fleet. In fact, if Athens had a fleet at all it was due to the courage and persistence of this one man.

When Athens triumphed over the Persians in BC 490 most Athenians believed the threat was over. Persia was far away, and the bloody nose the “barbarians” had received at Marathon seemed to end the matter once and for all. But Themistocles was unconvinced the Persians were gone for good. He believed Athens’ salvation, and ultimately all of Greece’s as well, would be in sea power. But beyond the Persian threat, there are indications he dreamed of Athens as the hub of a great empire, where trade and tribute would flow into the city from every part of the Mediterranean world.

In the BC 480s Themistocles was instrumental in developing the port of Piraeus, about four miles from Athens. Work was put in hand to build a naval arsenal and harbor facilities, but progress was slow. In November, BC 486, King Darius died and was succeeded by his son Xerxes. In the later years of his reign Darius had been preoccupied by a revolt in Egypt and other matters, but never lost the idea of wreaking vengeance on the Greeks and adding them to his empire. Now it was up to his son to carry these projects to their conclusion.

Themistocles had a clear-sighted policy of naval development—the problem was how to make it a reality. Athens was engaged in an off-again, on-again war with nearby Aegina, an island in the Saronic Gulf some 19 miles (30 km) away. The Athenian fleet was second-rate at the time, at one point mustering only 50 triremes.

Serendipity, or a Gift From the Gods?

Clearly something had to be done—but first there was the problem of finance. Ships can be expensive, and Athens lacked the resources for a full-scale building program. But in BC 483-482, in the very nick of time, there was a major silver strike in the state mines at Laurium. This was a bonanza indeed, the financial foundations of Athens’ future greatness, and produced a coinage so stable Athenian money became common throughout the Aegean.

A conservative politician named Aristides proposed that the silver profits be distributed among the citizen body, with each man getting 10 drachmas. Themistocles was aghast; he wanted the money to be poured into a shipbuilding program. If Aristides’ proposal carried the day, a defenseless Athens might soon have cause to regret their shortsightedness, but then it would be too late.

The issue of the silver profits had to be decided by the ekklesia or Assembly by majority vote. The Assembly was a large, potentially fractious body, and a politician needed to be eloquent to influence it. Themistocles knew the Persians were a distant threat to most Athenians, so any arguments about a defensive/offensive fleet were bound to fall on deaf ears. However the stalled war with Aegina was on everyone’s mind—after all, Aegina was in the neighborhood, and naval actions against the recalcitrant island had been embarrassing failures. Themistocles urged a naval buildup in the context of the Aeginian war and won the day.

6000 Votes to Banish a Man

Conservative elements were still not convinced, grumbling that he had “degraded the people of Athens to the rowing pad and oar.” Aristides and his faction were bound to stir up trouble, so Themistocles decided to remove his rival. In short order an ostrakophoria or ostracism vote was arranged. If a man were ostracized he would be banished from the city for 10 years. No other penalties were imposed, and his citizenship and property remained intact. The names of candidates for ostracism were scratched on potsherds; it took six thousand such votes to banish a man. In BC 482 Aristides was ostracized, thus removing a major barrier to the Themistoclean naval program.

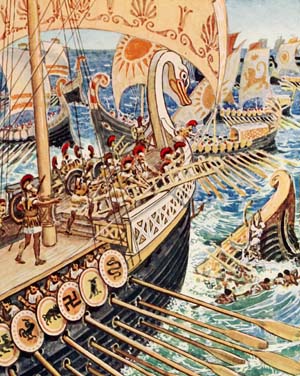

By the spring of BC 480 the Athenian navy boasted some two hundred triremes, making it the greatest power in Hellas. The trireme was the battleship of its day, propelled by three banks of oars and armed with a powerful bronze ram in the prow to hole and sink enemy vessels. Around this time Themistocles had won election to the Board of Generals for the year BC 480-479. As a strategos (general) he would be in a position to influence events. Earlier, in BC 481, a “Hellenic League” of various Greek states had assembled at the Isthmus of Corinth. Differences were settled and at least an embryonic unity achieved. The League Congress broke up, only to reassemble in BC 480 on the eve of the Persian invasion.

By now (about mid-480) the Persians had assembled a multinational army that patriotic Greek historians such as Herodotus reckoned at two million or so. Most modern historians disagree, placing Xerxes’ army at around 180,000 to 200,000, which was still a mighty host for the period. The Great King also had a huge fleet at his command which Herodotus numbered at 1,207 warships and three thousand transport vessels. Even allowing for propaganda inflation, Xerxes possessed a formidable fleet, because even though the Persians were not seafarers, many of their subject peoples were quite at home in Mediterranean waters. Xerxes’ armada included Ionian Greek and Phoenician ships, and it was said the Egyptian squadron was also among the best ever to put to sea.

By now (about mid-480) the Persians had assembled a multinational army that patriotic Greek historians such as Herodotus reckoned at two million or so. Most modern historians disagree, placing Xerxes’ army at around 180,000 to 200,000, which was still a mighty host for the period. The Great King also had a huge fleet at his command which Herodotus numbered at 1,207 warships and three thousand transport vessels. Even allowing for propaganda inflation, Xerxes possessed a formidable fleet, because even though the Persians were not seafarers, many of their subject peoples were quite at home in Mediterranean waters. Xerxes’ armada included Ionian Greek and Phoenician ships, and it was said the Egyptian squadron was also among the best ever to put to sea.

When the Athenian delegation returned from Delphi people debated the interpretation of “wooden walls.” Older, more conservative people were sure that the defense should center around the Acropolis, which had once been encircled by a wooden wall. The Acropolis (“upper city”) was the high summit were the Temple of Athena Polis (“Athenia of the City”) was located, a building that housed the sacred wooden statue of the goddess. Since Athena was the patron and protector of Athens it seemed inconceivable she would let her sanctuary be violated.

Themistocles had a different understanding. To him, the “wooden walls” were the hulls of the Athenian fleet. Some felt the oracle had predicted a Greek defeat off Salamis island; not so declared Themistocles. Surely Apollo was not on the Persian side, and if he was predicting Greek defeat, he would have called Salamis “luckless” or “damned,” not “divine.” Themistocles insisted that Apollo prophesied Greek victory, and his arguments calmed fears and stiffened Athenian resolution.

Leonidas and His 300 Spartans Muster with 7000 Greeks at Thermopylae

Meanwhile Xerxes had a bridge of boats built at the Hellespont, today’s Dardanelles, and proceeded to bring his huge army across from Asia into Europe. By about May BC 480, Xerxes’ entire force was assembled at Doriscus in Thrace. Generally speaking, he intended to probe southward, his fleet providing support as well as guarding his left flank. By mid-June the Persians were on the march, and region after region sent earth and water to Xerxes in token of submission. Soon all Thessaly was in the Persian camp, and Boeotia—the cities of Thespiae and Plataea excepted—followed suit.

After some abortive maneuvers the anti-Persian Hellenic League decided to block Xerxes by land at Thermopylae and by sea at Artemisium. Thermopylae (the name means “hot gates,” from a nearby hot springs) was a narrow defile that was edged on one side by mountains and on the other by sea. The Allied land force was composed of some seven thousand troops, but the best soldiers were the three hundred Spartans under their King Leonidas.

The Greek naval position at Artemisium had much to recommend it. Artemisium is on the island of Euboea, a long finger of land that protects central and southeastern Greece, including Attica. Artemisum’s shoreline featured a flat plain about 10 miles long, its sandy features cut by small streams and littered with white pebbles washed ashore from storms. This flat, shelving beach was ideal for hauling triremes ashore, a common practice of the period.

By stationing their fleet at Artemisium the Greeks guarded the entrance to the Malian Gulf and Leonidas’s flank at Thermopylae, and also kept watch on the sea lanes at Skiathos and Skopelos. The Allied fleet set off for Artemisium in late July. There were 271 vessels all told, of which 127 were Athenian or at least provided by Athens. Each trireme was crewed by two hundred men, a figure that included 170 rowers. This was an enormous drain of manpower, even for a populous state like Athens. The Athenians refitted 47 older vessels, then crewed them with inexperienced but eager Plateans and volunteers from Chalcis. This “hand me down” system worked well; experienced Athenian crews were then released to man newer, front-line triremes. Sparta, Corinth, Aegina, and a scattering of other Greek states also contributed triremes, and the fleet was rounded out by a few penticosters, single-banked galleys of 50 oars.

The Greeks arrived at Artemisium in early August, and not a moment too soon. In spite of the common Persian threat, many of the Allies were still jealous of Athens and refused to serve under an Athenian commander in chief. Eurybiades—a Spartan with no experience in naval affairs and by most accounts an unimaginative man—was given command of the Allied fleet. Themistocles acquiesced in the matter of command; he knew fragile Greek unity had to be maintained and probably felt he could “guide” Eurybiades behind the scenes.

Another Gift From the Gods

Nature itself now came to the aid of the Greeks. The huge Persian armada was strung out for miles from Mt. Ossa southward when a meltemi—a furious gale—stuck them almost without warning. Ships were dashed upon the rocks, and even those that survived were badly battered. The Athenians believed that Boreas, god of the wind, had come to their aid. But most of the Persian fleet weathered the storm and continued on to the vicinity of Artemisium. Even with substantial losses, the Persian armada still outnumbered the Greeks.

Xerxes decided on a bold gamble. He dispatched some two hundred vessels through the Skiathos channel, then eastward down the coast of Euboea. The intention was to circumnavigate the island and take the Greek fleet from the rear. It would be a long journey, taking some three or four days to complete if successful. In the meantime, if the Greeks cooperated and remained quiescent, further repairs on the battered main fleet could be affected. It was a good plan, because one of the reasons the Greeks were at Artemisium was to “cork” the Euboean channel and to guard the Euripus, the narrow waterway that separated Euboea from the mainland.

If ancient sources are to be believed Admiral Eurybiades and some of the other Greeks were getting cold feet about fighting at Artemisium. Rumors began to circulate that the Allied fleet would withdraw, a prospect that terrified the Greeks living on Euboea. A delegation of Euboeans went to Themistocles, imploring him to use his influence to prevent the fleet from leaving. To sweeten their arguments the Euboeans gave the Athenian a bribe of 30 talents of silver.

Actually they were “preaching to the converted”; Themistocles had no intention of leaving Artemisium, but put the bribe money to good use. Pretending the silver was his own, Themistocles gave five talents to Eurybiades and three talents to the Cornithian admiral Adeimantus. These “under-the-table” transactions strengthened their wavering resolve, and it was decided the fleet would stay. The episode is typical of Themistocles’ shrewd manuuvers; he bribed the admirals with someone else’s money and was still left with a profit.

Hundreds of Warships Row Forward in Unison

On August 18, about 4 in the afternoon, the battle of Artemisium began in earnest. Details are extremely sketchy, but clear enough in broad outline. The Greeks came forward in battle formation, probably line abreast, and the rising and falling of so many oars in unison must have been majestic as well as mesmerizing. The oarsmen in each trireme worked with a will, and their rhythmic exertions—coupled by a stifling August heat—soon caused well-muscled bodies to glisten with sweat.

The Persians could scarcely believe their eyes, and must have thought the Helenes had taken leave of their senses. Xerxes’ fleet included many Ionian Greeks who had little love for the Persians, but there were also Phoenicians and others who were eager to come to grips with the enemy. As the Greek historian Herodotus relates, some Persian units were particularly keen to capture an Athenian ship, because the Athenians were known as the best seamen and possessed the best ships.

The Persians could scarcely believe their eyes, and must have thought the Helenes had taken leave of their senses. Xerxes’ fleet included many Ionian Greeks who had little love for the Persians, but there were also Phoenicians and others who were eager to come to grips with the enemy. As the Greek historian Herodotus relates, some Persian units were particularly keen to capture an Athenian ship, because the Athenians were known as the best seamen and possessed the best ships.

Again, ancient sources say little about specific tactics, but apparently the Persian fleet attempted a maneuver called the periplus, a kind of envelopment where they could use their superior numbers to hit the Greeks in the flanks. The sea boiled with flailing oars as ships tried to jockey into position. The Greeks saw the Persian intention and countered with a maneuver of their own, the kyklos or defensive “circle,” and the Greeks peeled off one by one to form its “spokes.” The sterns of each trireme formed the inner part of the circle, with the lethal prow rams facing outward in a prickly “hedgehog” defense. Once the circle was formed, the Persians could make little headway.

At a signal the kyklos “exploded,” the Greek triremes expanding out in all directions to take the offensive. The kyklos became an expanding “starburst” of Greek ships that rammed or captured vessel after vessel. It was said that the Greeks captured 30 Persian vessels before night fell and they were forced to break off the action. Somehow it was fitting that the first Allied ship to capture an enemy vessel was an Athenian trireme commanded by a man named Lycomedes. The Greeks had not only held, they had bested, a superior force. They must have been elated, but Themistocles knew it was only the first round.

That evening a powerful storm arose, bringing with it mountainous seas, driving gales, and torrential rains. Once again, the Persian fleet suffered terribly and many ships were wrecked on the rocky shores.

Round 2 Begins

Around noon on August 19 a squadron of 53 Athenian triremes reached Artemisium. The reinforcements were welcome, but the news they brought caused even more rejoicing. It seemed that Xerxes’ Euboea-flanking fleet—the same that was attempting to sail around the island and take the Greeks from the rear—had been decimated by the storm the previous night. Some sources claim this flanking squadron was totally destroyed, which is dubious. It was clear, however, that Xerxes’ ploy had failed, and with that failure a serious threat had been eliminated.

No doubt buoyed by the news, the Greek fleet staged a kind of large-scale raid on Xerxes’ Cilician squadron, wrecking several ships before withdrawing unmolested. It was said that the Persians were humiliated that the Greeks had bested them in two consecutive engagements. In any case, the Persians resolved to clear the channel once and for all by mounting a major offensive August 20. All of the Great King’s naval strength was marshaled for the big push: Egyptians, Cilicians, Phoenicians, and subject Greeks from Ionia, Caria, and the Hellespont were included in the effort. This was to be an all-out, victory-or-death assault, the Persians making sure Greek naval power was destroyed forever.

The Persian armada came forward in a huge crescent formation, a wooden convex whose ram-tipped flanks threatened to envelop and “swallow” the Greek triremes. But Persian numbers were so great they tended to foul one another, thrashing and flailing like a school of fish in a net as oars interlocked and hulls rubbed and bumped together.

This tended to help the Greeks, but the contest was far from one-sided, however, and the Greeks were roughly handled by the Persians. The Egyptians captured five Greek vessels and their crews, a notable feat that even Herodotus speaks of with admiration. Greek triremes were designed for ramming enemy ships, not grappling and boarding. Their sleek hulls could cut through the water with the effortless grace of a dolphin, and when propelled by skilled oarsmen they had a quicksilver quality that made them hard to pin down. Yet an Athenian trireme carried only about 10 hoplite marines and perhaps four archers. By contrast, enemy ships could carry a complement of 40 marines, making Greek ships vulnerable if boarded.

Herodotus records that the Egyptians wore cuirasses and were armed with long swords and battle axes, weapons equal to a hoplite’s spear or sword. Once the hoplite marines were overwhelmed, the 170 rowers had little choice but to surrender. Greek oarsmen carried no weapons and wore little clothing, and so were vulnerable.

Clenched in a Stalemate With Both Sides Bloodied

When the day ended neither side could claim a clear-cut victory, though the Greeks probably did more damage to the enemy than they themselves sustained. Nevertheless the Greek fleet had taken some severe blows, and it was said that half of the Athenian squadron had been damaged.

As night fell the Greeks fished out their dead from the waters and gathered wood for funeral pyres. Triremes too damaged for further service were also put to the torch. Plutarch, a Greek historian living in Roman times, wrote that a layer of ash from the pyres and the burned wrecks could still be seen at Artemisium six hundred years after the battle. It was fitting that the ashes of the Greek sailors mingled with the sands of Artemesium, becoming part of the very native soil they died to defend.

The Last Stand of King Leonidas of Sparta

The night was dark, illuminated by the flickering flames that greedily consumed the battle dead, and the rising smoke added a physical pall to an already uncertain mood. The gloom only deepened when a swift triaconter—a single-banked galley of 30 oars—under Habronithus arrived with terrible news. A Greek traitor had shown the Persians a mountain pass that flanked Leonidas’s position at Thermopylae. The Spartan king and some seven thousand Greek Allied troops had held the pass for several days, inflicting heavy casualties on the Persian host, but once their position was flanked it became untenable.

Leonidas and his three hundred Spartans chose to stay, although this would mean a death sentence. Perhaps 1,500 Allied troops also elected to remain, and the rest withdrew. On August 20, the same day as the battle of Artemisium, Leonidas and his troops were overwhelmed and perished to the last man. Later, a monument was erected over the Spartans’ grave that was a fitting tribute to their heroism and self-sacrifice. Its legend ran: O xein angellein Lakdaimoniois hoti tede keimetha tois keinon rhemasi peithomenoi, or “Tell the Spartans, stranger passing by, That obedient to their laws we lie.”

For the moment, however, the tidings of Thermopylae were grave indeed. Artemesium was becoming untenable, and there was nothing more to do but withdraw the fleet as soon as possible. As it was, many of the Greek ships were barely seaworthy and badly in need of repair. Rams were cracked and sprung from their timbers, and hulls bore terrible battle scars. Enemy rams had gouged holes that were near the waterline, and oars had been splintered to “kindling.” Blood stains were everywhere, crimson blotches that were freshened by the wounds of the injured that were carried aboard for evacuation.

Persia’s Human Avalanche Rolls Over Athens

With Thermopylae secure, the Persian juggernaut rolled south with little or no opposition. Xerxes’ human avalanche swept through Boeotia and was soon on the outskirts of Attica, Athens’ home territory. Themistocles issued an order (keygma) for the total evacuation of the city. Men serving with the fleet were allowed shore leave to gather women, children, other dependents (including slaves), and perhaps some household goods, and bring them to Piraeus. Once in the seaport, the dependents would take ships to Salamis or Aegina, islands in the Saronic Gulf off Attica.

Apparently some people had already been evacuated to Salamis, Aegina, and (relatively) far-off Troezen in the Peloponnesus some weeks earlier, but a substantial portion of the Athenian population had remained behind. Now, the evacuation would be total. Athens was transformed into a hive of activity, its narrow streets and broad Agora thronged with departing people. It was a melancholy procession, a kaleidoscope composed of every age, sex, and economic condition.

The lifeblood of any city is its people, and Athens was being bled white of its resident population. Its streets and lanes were like veins, producing a hemorrhage of humanity that soon rendered the city a lifeless corpse. Yet a small die-hard garrison still held the Acropolis, confident that their reading of the “wooden walls” prophecy was the correct one.

The shoreline of Piraeus was now the scene of heart-rending partings and tearful goodbyes. Athenian men put dependents on waiting ships “and themselves crossed over to Salamis, unmoved by the cries and tears and embraces of their own kin.” Since space aboard ships was limited, the aged and infirm were left behind. Household pets also remained in Athens, because wartime emergencies left no room for sentiment.

The last overcrowded ship left Piraeus August 26, and the Persians arrived in Athens a day later. Apart from the Acropolis and a few pockets here and there, the city was basically empty. Athens was quiet, save for the mournful howling of dogs that had been left behind, their baying a funeral dirge for a stricken city.

The Persians swept through the city like a swarm of locusts, pillaging and burning as they went. Terms were offered to the Acropolis garrison, but were stoutly refused. When the Persians tried to mount an attack on the main gate, the defenders hurled boulders down the slope to crush them. Persian archers climbed the nearby Areopagus hill and shot fire arrows at the Acropolis. Soon the wooden barricade the defenders had erected was ablaze.

Finally a force of Persians managed to climb a steep cliff to the Sancuary of Aglaurus, and from there gained entrance to the Acropolis. All the defenders were put to the sword; none was spared, not even noncombatants who were cowering within the temple sanctuary. All buildings on the summit were torched, including the Temple of Athena Polis. Luckily the sacred wooden cult statue of Athena had been evacuated some time before.

Forcing Persia’s Hand: A Naval Showdown

The city states of the Peloponnesus were now obsessed with their own defense. The Pelopponesus was a near-island connected to the mainland by a narrow strip called the Isthmus of Corinth. Led by Sparta, the Peloponnesian states built a five-mile-long defensive wall across the Isthmus to block the Persian advance. The men from the Peloponnesian states also wanted to make a naval stand at the Isthmus. The waters off Salamis island seemed too confining; if defeated, it was felt they would be bottled up and unable to escape. On the other hand, if defeated at the Isthmus, member states could retreat home for a last stand.

In Themistocles’ view this was a recipe for disaster. Defeat at the Isthmus would mean total defeat for the Greek cause, because once the Greek fleet scattered the Persians would have control of the sea. Once the Persians had control of the sea, they could land anywhere in the Peloponnesus, easily outflanking the Isthmus of Corinth wall that was being so painstakingly erected.

In Themistocles’ view this was a recipe for disaster. Defeat at the Isthmus would mean total defeat for the Greek cause, because once the Greek fleet scattered the Persians would have control of the sea. Once the Persians had control of the sea, they could land anywhere in the Peloponnesus, easily outflanking the Isthmus of Corinth wall that was being so painstakingly erected.

Themistocles declared that fighting at the Isthmus “would be greatly to our disadvantage, with our smaller numbers and smaller ships.… The open sea is bound to help the enemy, just as fighting in a confined space is bound to help us.” The Athenian concluded by saying, “If we beat them at sea … they will not advance to attack you at the Isthmus.”

His proposals were beginning to find favor, but there were a few stubborn holdouts. The Corinthian admiral Adeimantus bluntly told Themistocles to shut up, since he was a man without a country. It was a none-too-subtle reference to the evacuation of Athens and its subsequent occupation and destruction by the “barbarian” Persians.

Far from being cowed by Adeimantus’s rudeness, Themistocles shot back that on the contrary, “The Athenians have a city and a country greater even than Corinth, as long as they have two hundred ships full of men; no Greeks could beat them off if they chose to attack.” Turning to Euryabiades, Themistocles produced his trump card in the form of a threat. If the Allies didn’t follow his plan, Athens would withdraw from the war and immigrate to Italy. “If you don’t follow my advice,” Themistocles warned, “we will pack up our households and sail off to Sirus in [southern] Italy.”

Eurybiades and the other Allies knew that Athens was providing the bulk of the Greek fleet and had the best ships and crews. Athenian withdrawal would mean Persian victory. A vote was taken, and Themistocles’s suggestions won handily. It had been a bitter and at times hard-fought debate, but the deliberations had borne good fruit: The Greeks would fight at Salamis.

Questionable Allegiance? A Tricky Gamble

Themistocles’s next task was to lure the Persians into attacking at Salamis, where their superior numbers would be neutralized and the Greeks would have a better than even chance to win. The Athenian knew what he had to do. He sent for Sicinnus, a trusted slave, and secretly dispatched him with a letter to Xerxes. Sicinnus was rowed out to a Persian ship, where he delivered the secret missive. Eventually the message made its way to Xerxes, who must have been greatly heartened by its contents. Themistocles told the Great King that he had changed sides and was now willing to inform on his fellow Greeks. In fact, as a show of good faith, Themistocles warned Xerxes that the Greeks were preparing to escape. If he moved fast enough, Xerxes could block all exits and prevent the elusive Hellenes from slipping the net.

As events unfolded it seemed Themistocles was “preaching to the converted”—telling Xerxes exactly what he wanted to hear. Autumn was approaching, and winter was not far behind. The Persians had already suffered from storms, and fall would bring even more inclement weather. The Great King was far from home, and his prolonged absence might encourage subject peoples to revolt.

Some of his subordinates, like his ally Queen Artemesia of Halicarnassus, urged caution and delay, arguing that fragile Greek unity would crumble over time. Xerxes was too impatient for final victory to listen to such advice, though it was said he was “pleased” with her counsel.

Patience and Arrogance Collide

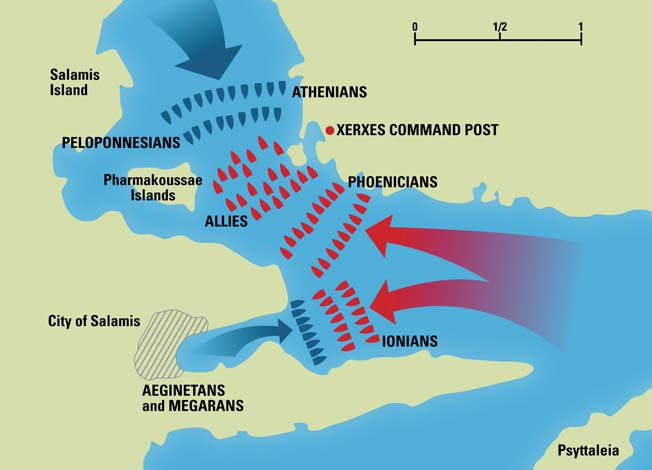

Themistocles’s enticing message tipped the scales in favor of action. If the Greeks intended to flee, it was critical that all potential avenues of escape be covered. The Egyptian squadron was ordered to sail around Salamis to blockade the Megara channel, and two other squadrons were placed on station on either side of Psyttaleia island (today’s Lipsokoutali) to pounce on unwary Greek vessels. A fourth squadron patroled waters to the south: Nothing was left to chance.

The Persians stayed on alert the entire night, waiting in vain for an attempted breakout that never came. Xerxes was ready to attack the moment the Greeks turned tail—in fact, he intended to force the Salamis narrows, confident the Hellenes would be too intent on flight to offer effective resistance. As if in anticipation of a sea battle in the narrows, Xerxes garrisoned Pysttaleia with four hundred troops. The island was near the Salamis channel and an obvious place of refuge for battle-shipwrecked sailors on both sides. The Persian troops would be in a position to aid their own sailors but capture or dispatch Greek mariners.

Xerxes set up a command post on the lower slopes of Mount Aegaleus, a position that afforded him a good view of the Salamis channel and a “ring side seat” for the coming clash. The Great King was seated on a golden throne, surrounded by guards, attendants, and various functionaries. Scribes were on hand to record the events of the coming battle, with special emphasis placed on deeds of courage—or cowardice—performed by his captains. Heroism would be rewarded, cowardice or ill judgment punished.

In the meantime a Tenian trireme—from one of those Hellene localities under Persian rule—deserted and gave the Greeks full details of Xerxes’ plans. Themisocles must have been pleased, because it was obvious the Great King had taken the bait. The fate of Greece would now depend on a sea battle.

The exact date of the Battle of Salamis is a matter of some conjecture and considerable debate. It was probably fought in the third week of September, BC 480. Some authorities place it on September 23, others September 20, and a few September 28. In similar fashion the number of ships involved is unknown; the Greek fleet had about three hundred ships, of which half were Athenian. Tradition says the Persians had 1,200 vessels, but modern authorities place it somewhere in the 650-800 ship range.

Greek dispositions show a great measure of planning and tactical expertise. The Aegintan and Megaran contingents formed a far right wing that sheltered within the confines of Abelaki Bay, admirably placed for an ambush. The rest of the fleet was arrayed across the Salamis channel narrows, with the Athenians occupying the far left, the various Peloponnesian units next to them. It has been estimated that the Greeks deployed their ships in line-abreast formation, with an in-depth arrangement of three such lines.

A Ruse by any Other Name…

It was still early morning when the Corinthian squadron hoisted sail and headed north toward the bay of Eleusis. This was a significant maneuver, and highly suggestive of panicked flight. The Greeks did not employ sails in battle, but left them ashore to be collected at a later time. It must have seemed that the Greeks were retreating, seeking to escape by sailing around Salamis via the bay of Eluesis and then exiting through the Megara channel.

The “retreat” seemed real and a confirmation of Themistocles’s “traitorous” message. Xerxes must have been delighted, congratulating himself that he had taken the letter seriously. And if the Egyptians were in place blocking the Megara channel, it meant the Greeks were trapped. The Great King needed no further prompting; he ordered his fleet to advance up the Salamis channel narrows. The Phoenicians anchored the Persian right, which placed them opposite the Athenians. The Persian center was held by various subject states, including Lycia, Cilicia, and Cyprus. The left was occupied by the Ionian Greeks.

The Corinthian “flight” was more apparent than real, a clever ploy to deceive Xerxes into thinking the Greeks were retreating. Some authorities believe the Corinthian maneuver was more than just a ruse, and that they were sailing to do battle with the Egyptians at the Megara channel.

In any event the Greek fleet began to back water, seemingly giving way before superior Persian forces, but in reality luring the enemy into the narrow channel. Then, without warning, the Greeks went over to the offensive. The Greek trireme crews gave a hearty cheer, a thunderous cry of exaltation that carried over the water and echoed off the nearby Salamis hills. Somewhere a trumpet sounded, its metallic blare a summons to battle and a first note in a chorus of victory. Oars were worked with a will, churning the water to a froth, while the sweating crews sang a hymn, “Apollo, Saving Lord.”

Aphobia: Lacking Fear

The Greek ships moved forward, the Athenians in the lead. Athenian triremes gracefully plowed through the water, possibly reaching speeds upward of 10-12 knots (11-13 mph). Almond-shaped apotropaic eyes grazed on the prow of each ship, helping the trireme “see ahead,” and bronze rams plowed white furrows in the water that spread ripping wakes behind each vessel. Oarsmen kept up the relentless pace, their movements kept in time by the plaintive notes of an aulos, or double-reed flute, played by the ship’s piper. On each trireme oars dipped, rose, and dipped again, making the sea boil with white-flecked foam.

Lycomedes, one of the Athenian captains, was the first to capture an enemy ship. In token of gratitude to the gods he cut off the figurehead of the ship and dedicated it to Apollo the laurel bearer. But perhaps Lycomedes wasn’t the first in action; Greek war, like Greek politics, was fiercely partisan and a product of the internal dissentions that plagued the Hellenes.

Lycomedes, one of the Athenian captains, was the first to capture an enemy ship. In token of gratitude to the gods he cut off the figurehead of the ship and dedicated it to Apollo the laurel bearer. But perhaps Lycomedes wasn’t the first in action; Greek war, like Greek politics, was fiercely partisan and a product of the internal dissentions that plagued the Hellenes.

Armeinias, another Athenian trirarch (captain), was so eager to come to grips with the enemy he outdistanced the others. Soon he saw a large Phoenician ship nearby, a tempting target, but a target fraught with special dangers. Ameinias’s boldness was a display of what the Greeks called aphobia, fearlessness, because the Phoenician ship was larger and probably carried more fighting personnel. This was also no ordinary vessel, but the flagship of the Phoenician squadron with its commander and brother of Xerxes, Admiral Ariamenes, aboard.

The two ships plowed into each other with terrific impact, each punching a hole in the other in such a way that they were locked in a deadly embrace. Phoenicians preferred to grapple and board, but the two ships’ predicament made such maneuvers unnecessary. In a short but bloody contest, the Athenian crew beat back a Phoenician boarding attempt, no easy matter because Greek ships usually carried far fewer marines. Admiral Ariamenes was impaled on Athenian spears and his bloodied corpse pitched into the sea. Its victory complete, the Athenian trireme managed to extricate itself before its prize sank to the bottom.

A Critical Strike to the Persian Armada!

The loss of the flagship was a catastrophic blow to the Phoenicians, leaving them leaderless and without direction precisely at a time when they needed it the most. The Phoenician squadron became confused and disoriented, a condition made worse by the narrowness of the channel. Some Phoenicians began to panic, backing water in retreat as others pressed forward to the attack. Vessels tangled, unable to properly maneuver, and many became so fowled they presented the Athenians with easy targets. The Athenians descended on the Phoenicians like a pack of ravenous wolves on a flock of sheep, their rams goring enemy ships almost without impunity. The noise of battle grew louder, each ram’s impact providing a sickening thud as its bronze beak tore through timbers.

Other Greek triremes edged along the sides of Persian vessels, their rams shearing off oars as they went. Once a trireme’s “legs” were “clipped,” and one or both sides of oars were gone, it was literally dead in the water. About this time—the chronology is imprecise—the Aegintans and Megarans emerged from Abelaki Bay and hit the Persian fleet—here largely Ionians—in flank. Hidden behind a headland, their presence had gone undetected until the last moment. Now, the Greek plan unfolded, revealed in its many dimensions. What the Hellenes were executing was a periplus, using the narrowest part of the Salamis channel to neutralize a superior enemy. Initially the Greek fleet backed water with rams facing the foe, the Corinthian “retreat” an added smokescreen. True to the periplus scenario, the Persians had followed the retreat down the narrows, unwittingly exposing their vulnerable hulls to a flank attack from Ambelaki Bay.

Saved by the “Wooden Walls”

In the ensuing melee Persian ships capsized or sank outright, plunging crews into the water to try and survive as best they could. Many of the Persians drowned, not being able to swim. Those that managed to cling to wreckage were dispatched by passing Greek triremes as they bobbed helplessly about. Not bothering to waste arrows or spears, the avenging Hellenes kept “hacking and striking” the Persians with broken oars as if they were “tuna or some haul of fish.”

Xerxes watched the battle with a growing, if impotent, rage. Phoenicians who survived the Athenian assault were brought before the Great King, who listened to their excuses with ill-disguised contempt. He had them beheaded on the spot as penalty for failure. When Queen Artemesia’s ship rammed a friendly vessel in an attempt to escape, Xerxes mistakenly thought she had attacked a Greek warship. “My men behave like women,” he lamented, “and my women like men!”

The setting sun’s last rays shone on a panorama of utter destruction. Broken oars, pieces of mast, and other wreckage floated about, and bobbing corpses dyed the normally blue waters crimson. Many thousands of dead bodies polluted the channel, eventually washing up on beaches like human flotsam. Most of the dead were from Persian ships, because Greeks knew how to swim and could save themselves.

Heads Hung Low, Heads Raised High

For Xerxes this battle wasn’t merely a setback, it was a debacle of major proportions. His proud fleet had been defeated and routed, and the survivors were so shaken that a renewed offensive action was out of the question. Most accounts agree the Greeks lost 40 triremes, the Persians two hundred. It was an overwhelming victory, a victory that saved Greece from foreign domination.

Xerxes went home to Persia, taking the bulk of his land army with him. A substantial Persian force under Mardonius remained in Greece, only to be defeated at Platea in BC 479. Athens now entered its golden age, a time of creativity and greatness that laid the foundations of Western civilization. It was a flowering made possible by the “wooden walls” of Salamis.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments