By Mason B. Webb

During World War II, the United States fielded 16 armored divisions, and all contributed to the Allied victory. But perhaps the one with the most storied history is the 10th Armored Division—nicknamed the “Tiger” Division and the “Armoraiders.”

The division was activated at Fort Benning, Georgia, in July 1942, with Maj. Gen. Paul W. Newgarden, a Patton disciple, at the helm. “Terrify and Destroy!” became the 10,610-man unit’s battle cry. The 10th Armored went on to complete its training at Camp Gordon, Georgia, but tragedy struck even before the division could be deployed for combat.

General Newgarden and Colonel Renn M. Lawrence, commander of Combat Command B (an armored division’s equivalent of an infantry regiment), had been attending a conference at Fort Knox, Kentucky, and on July 14, 1944, had taken off in a small plane from the post to return to Camp Gordon to review the division in celebration of the anniversary of his assuming command. Near Chattanooga, Tennessee, their small plane went down in a storm, killing all five men on board.

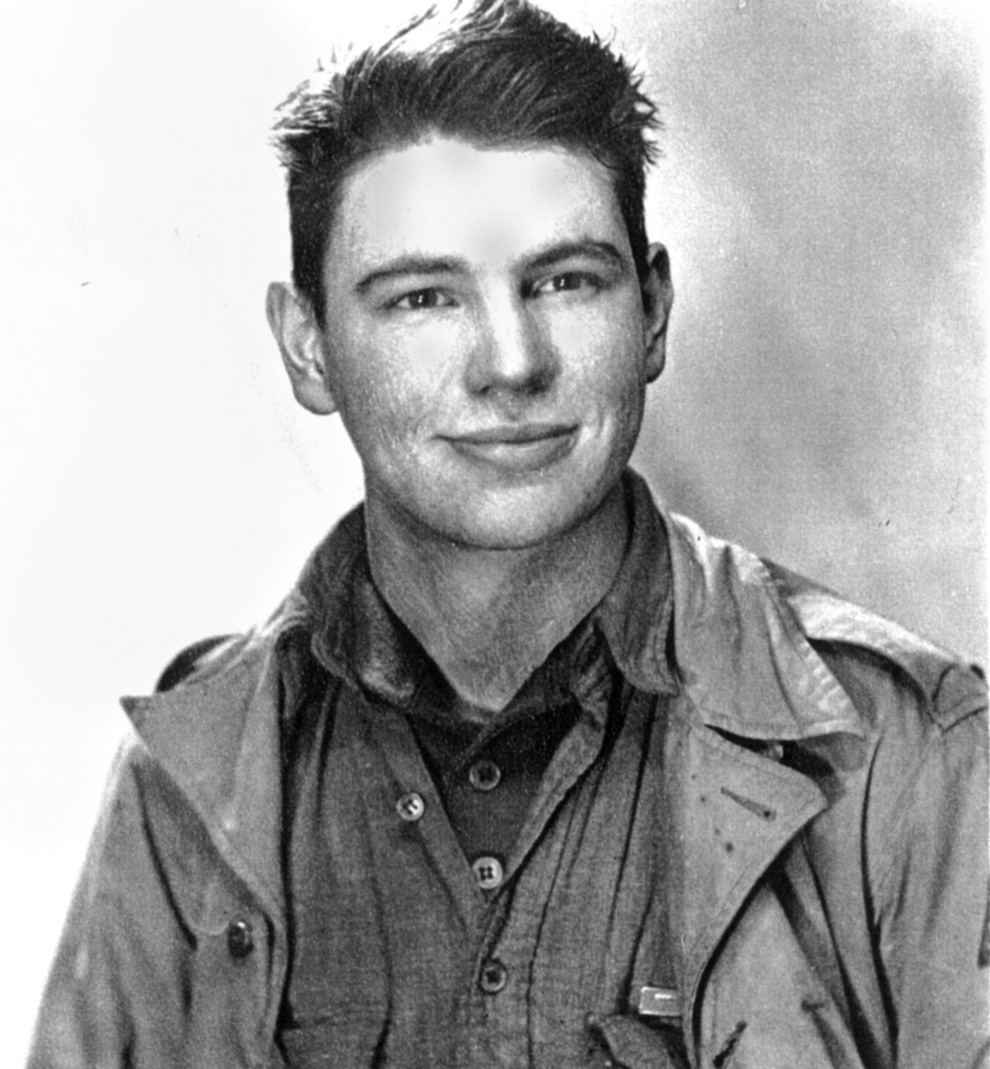

A week later, Maj. Gen. William H.H. Morris, Jr., took command of the grief-stricken Tigers. A division historian wrote, “Just as General Newgarden was an expert trainer of men, General Morris was a master tactician.”

Morris (West Point, 1907) had seen action in France during the First World War as a member of the 90th Division. After the outbreak of World War II, he became the 6th Armored Division’s commanding general and was given his second star. He was later appointed to command XVIII Corps in the U.S. but, upon learning of Newgarden’s death, he requested that Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall demote him and allow him to command the 10th Armored; Marshall agreed.

The division, which called themselves the “Armoraiders,” arrived at Cherbourg, France, on September 23, 1944, and, after being initially assigned to Ninth Army prior to embarkation, became part of Patton’s Third Army. It had missed out on the battle for St. Lô, but there was plenty of combat still ahead. After a month of training near Cherbourg, Morris’ men moved out and headed across France to Mars-la-Tour, just south of Luxembourg, where it received its baptism of fire on November 2.

On November 16, Corporal Bob Weber, the company clerk in A Company, 54th Armored Infantry Battalion, 10th Armored Division, wrote in his diary, “Crossed the flooded Moselle River on pontoon bridge with the 11th Tank Battalion in the morning at Malling. Cold and snow. Saw first Germans—dead and alive—and took 34 prisoners that day. Spent the night on guard in a ditch by a railroad embankment east of Laumesfeld. Freezing night!

“Turcotte was killed by an 88mm shell through Cronin’s half-track. Someone in the 1st platoon killed a German motorcycle rider who came up the road after nightfall. Captain Ralph C. Maddox, of the 1lth Tank Battalion, was our team commander and he was killed by a mortar shell, so our company commander, Captain Arthur C. Eisberg, replaced him as commander of the team.”

Three days later Weber wrote, “We were shelled during the day and had several casualties, some civilian. One little man who gave us some apples when we entered Filstroff was killed during the shelling.

“At night we moved anti-tank guns up on the hill next to the cemetery above town. Just as we were moving the last [gun] up and getting into the peeps [another term for jeeps] to go back, 88s began whamming all around us. I jumped out and into a patch of stickers and thorny weeds and buried my face into them. We moved out that night. Blew the bridge. Made a thrust towards Orscholz, Germany.”

After being stopped by heavy shelling, Weber’s unit turned back to Buschdorf and made camp on a grassy hillside. “Before long,” he wrote, “We had churned up mud 10 inches deep around the halftrack. We dug slit trenches and holes. Then it rained and snowed and got muddier than Hell while we stayed there. We were plenty cold and wet. We were shelled once in a while. Al Phenes and I shared a foxhole with water in the bottom of it, but he sat in the water and wouldn’t get out. It was miserable.”

On Thanksgiving Day, Weber noted, “Had kidney stew and a shelling along with it. Sgt. Earle dished out the stew. The Germans dished out a mortar shell that I swear lifted up the front end of our halftrack. Late that day we pulled back into [Buschdorf] and bedded down in a stone barn. At least straw is warm and comfortable and the barn gives protection.”

A few days later came Patton’s siege of Metz, France, on the Moselle River.

While the U.S. 5th and 95th Infantry Divisions assaulted the city, the 10th Armored was ordered to cross the Moselle and circle to the north and east of Metz to cut off the German garrison’s lines of communications and supply, and to ensure that no defenders escaped toward their homeland.

To break the siege, the German high command sent reinforcements rushing towards Metz, only to run head-on into the advancing Armoraiders, who proved that even novices to battle, if well led, could be an unstoppable force.

Soon the 10th Armored was fanning out into the Saar Basin. William Brown, a lieutenant at the point of Task Force Cherry (Lt. Col. Henry T. Cherry), was credited as being the first man in the Third Army to cross the German border.

Morris’ men had done remarkably well in their first major combat action. They had liberated 100 square miles of France, occupied 10 square miles of Germany, taken 2,000 prisoners, repulsed 11 counterattacks, and inflicted serious casualties on the enemy.

The first half of December was spent in a stationary position while tanks and equipment were repaired, replacements arrived, and Patton waited for much-needed supplies of fuel to arrive before continuing the advance.

The Germans also used this period of inactivity along the entire Allied line to lull Eisenhower and his generals into thinking that the Wehrmacht was content just to hold defensive positions. In actuality, the Germans were building up their forces for Hitler’s final major counteroffensive, which he called Operation Wacht-am-Rhein—but which would soon earn the name “the Battle of the Bulge.”

Battle of the Bulge

At dawn on December 16, 1944, the Germans broke out of their Ardennes Forest hiding places, smashed into American lines in Belgium and Luxembourg, and threatened to take Bastogne, the hub of the Ardennes road and rail network. Hardest hit were the veteran 28th Infantry and the totally green 106th Infantry Divisions, both of which were in the direct path of the Germans.

The 106th stood no chance; it was overrun by the enemy onslaught and crumbled, while the 28th held firm but took heavy losses.

Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, commanding the 21st Army Group, realized the importance of holding Bastogne, which was at the moment occupied by Combat Command Reserve of the 9th Armored Division. Bradley committed the 101st Airborne and 10th Armored Divisions to bolster 9th Armored. The 10th was split up, with Combat Command B (CCB) sent off to Bastogne while the balance of the division helped to hold the southern shoulder of the Bulge in Luxembourg.

Pfc. William R. Barrett, of the 10th Armored’s 420th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, recalled, “On the afternoon of the 17th we moved through Bastogne and set up in firing positions just north and east of Bastogne. There was no snow on the ground that day. We spent the night on the ground and woke up the next morning with seven inches of snow on us. From that position we never fired a shot. Then we had to move back through town to another site and got shelled going through.”

Morris’ men played a key role in the defense of Bastogne, and no contribution was more important than that of Task Force Cherry (Lt. Col. Henry T. Cherry). On December 17, German units—including the 2nd Panzer, 26th Volksgrenadier, and Panzer Lehr Divisions—approached the city, and their artillery and tank fire pummeled the defenders—the 9th Armored Division’s Combat Command Reserve.

Task Force Cherry consisted of Company A and two light-tank platoons of the 3rd Tank Battalion; Company C of the 20th Armored Infantry Battalion; the 2nd Platoon of Company D, 90th Cavalry Reconnaissance; and a few medics and engineers. Cherry established his headquarters in Neffe, just east of Bastogne.

At 8:30 a.m. on the 18th, advance elements of the 2nd Panzer Division ran into a 9th Armored Division roadblock set up by Task Force Rose near Lullange, Luxembourg—10 miles northeast of Bastogne. Unable to hold, the American task force fell back under heavy fire. The 9th Armored Division then found itself nearly surrounded by the 2nd Panzer, 26th Volksgrenadier, and Panzer Lehr Divisions.

The Army history continues: “On the evening of 18 December Team Cherry moved out of Bastogne on the road to Longvilly. Since he had the leading team in the CCB, 10th Armored column, Cherry had been assigned this mission by Colonel [William L.] Roberts [commander of the 10th’s Combat Command B] because of the immediate and obvious enemy threat to the east.” Maj. Gen. Troy Middleton, VIII Corps commander, had designated Longvilly as one of the three positions that Roberts’ CCB was to hold at all costs.

Cherry knew that Lt. Col. Joseph Gilbreth’s CCR, 9th Armored Division, was somewhere around Longvilly, but did not know exactly where. After dark, Cherry sent 1st Lt. Edward P. Hyduke, commanding the team’s advance element, to find it. Hyduke reached Longvilly at about 8:00 p.m. and discovered the village filled with vehicles and frightened, confused GIs.

No one seemed to know what the situation was; Gilbreth’s only orders were to “hold at all costs.” Hyduke told Gilbreth not to worry—Team Cherry was just down the Bastogne road. Cherry soon arrived at Gilbreth’s headquarters, and suddenly the gloom and doom that had pervaded CCR’s command post lightened.

At around 2:00 a.m. on December 19, Cherry learned that the hamlet of Mageret, three miles east of Bastogne, had been overrun by the 2nd Panzer Division and that his headquarters at Neffe was now cut off from the rest of his team at Longvilly.

Cherry ordered Captain William F. Ryerson to send a patrol up the traffic-jammed Bastogne-Longvilly road toward Mageret to reconnoiter the situation. The captain didn’t like what he saw and passed that information back; then Cherry ordered Ryerson to fight his way through Mageret while the advance guard conducted a rear-guard defense of Longvilly.

The U.S. Army’s official history said, “Longvilly, five-and-a-half miles [east-northeast of] Bastogne, was the scene of considerable confusion. Stragglers were marching and riding through the village, and the location of the enemy was uncertain, although rumor placed him on all sides.”

The road to Bastogne was still open, so Cherry decided to head back to Bastogne to tell Colonel Roberts about the situation. Before departing, he left orders for the advance guard to scout and establish a position about a thousand yards west of Longvilly while the main force, under Ryerson, took up defensive positions along the Bastogne-Longvilly road.

Cherry also positioned the cavalry platoon, four Sherman tanks, and seven light tanks to the south of Longvilly, where elements of Gilbreth’s CCR had been badly mauled and where the main gap in the defenses now existed. But the Germans were closing in.

The 2nd Panzer Division reached Longvilly at about this same time and collided with Team Cherry at a crossroads just outside Longvilly. The panzers overwhelmed Cherry’s men and pushed them back to the village.

Pfc. Barrett remembered, “We were shooting in all four directions, including the road we came in on. The enemy had surrounded us. We started running low on ammunition. The orders came through that if you saw our tanks, to shoot between them, because the enemy was behind them.

“We held our positions as best we could. Colonel Brown, commander of the 420th at the time, was hit by a shell that went over my head and hit the colonel and killed him. Major Crittenberger took over for him.”

The German armored force—2nd Panzer and Panzer Lehr Divisions—was too strong and smashed into Cherry’s men holding positions at Longvilly, sending them reeling backwards.

Luckily, the 101st Airborne Division had arrived in trucks from France just in the nick of time, and its elements began fanning out to blunt the German offensive. Cherry was ordered to retire to Bastogne, but that proved impossible because the highway was choked with American vehicles from other retreating units.

As historian John R. Bruning wrote, “Frantic M4 crews tried to get off the road and deploy, but they simply didn’t have the chance. Sherman after Sherman exploded in flames. Halftracks blew apart as armor-piercing shells tore through their gas tanks. The stricken GIs aboard the vehicles bailed out and scattered under a hail of machine-gun fire.”

Hundreds of GIs were killed or captured, and the snowy landscape became littered with wrecked and burning vehicles: 23 Shermans, 15 self-propelled howitzers, and 14 armored cars. As Bruning noted, “Team Cherry ceased to exist.”

Elsewhere, the Germans also nearly obliterated another 10th Armored task force, Team Desobry, at Noville. But the Americans hung on and, with the help of the newly arrived 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, dealt the Germans a heavy blow. Although the paratroopers and Desobry’s men suffered heavy casualties, the 2nd Panzer Division had it worse—35 tanks and over 500 dead.

Although fighting continued for a few more days, the Germans had shot their bolt and succumbed to increasing American replacements and firepower. It was time for the Yanks to continue their eastward march.

In Luxembourg, on December 21, Corporal Bob Weber recorded in his diary, “Pulled out in early afternoon and made a mounted march to Consdorf [southwest of Echternach, Luxembourg] where the Germans were trying to break through. They threw artillery, mortars, and rockets into the town…. HQ squad was to put up in a big house but the major wanted us to pull down the street, and we stayed in a barn across the street from the schoolhouse. Stayed in the schoolhouse that night as runner to our CP in the garage across the street.

“In the morning we passed our big house that we were going to put up in and it had a big hole over the door leading into our room where a huge shell had gone through. While in the schoolhouse, they pulled a guy out of his shot-up tank, dead.”

Four days later Weber wrote, “Christmas! And in Europe of all places—but I’m glad it’s Luxembourg instead of somewhere else, and at least we are in the rear today, which is a lot to be thankful for…. Luxembourg is a beautiful country…. Clean, neat houses, streets, intelligent people, and good, rich beautiful country. By all means it is the finest part of Europe.”

With the crisis in the Bulge at last over, Patton directed Morris’ tankers, accompanied by the 94th Infantry Division, along with the rest of Third Army to head southeast into the Palatinate region of Germany, taking the important railroad center of Zerf in the process.

Bob Weber noted on February 27, “Rode up the road blasting both sides and taking mortar and 88 fire all day. At Zerf we made a 90-degree turn north and headed for Trier. At one sharp turn—probably where we made the major change of direction—we stopped on the road and 88s began firing at us. We could see the shock waves in the air when the mortar shells exploded because it was sort of misty or foggy out across the fields.

“One fellow in the half-track ahead jumped out and was knocked over. The medics came over and looked at him but didn’t even bother to tum him over. We got out and jumped into V-shaped foxholes that the Germans had dug all along the road.”

The next day Weber’s unit took fire outside a village called Pellingen, set in rolling hills south of Trier. He recalled, “We had a hellish afternoon of mortar and direct artillery fire on us. Ten snipers in foxholes in the hill to the right of us eventually … gave up but not until one of them tried to jump out of his hole and run over the hill. He had a camouflage suit on and he ran several hundred yards before our machine guns knocked him down for good.

“Wayne McDuffee, our company mailman, was killed by a direct hit on the ring mount of the HQ squad half-track; Sgt. Earle was hit in the eye by the fragments of the same shell. Johnny Webb got a case of nerves and cracked up…. Lt. Lergner got hit severely and was evacuated to England eventually, and Sgt. Curtis Schrock was hit by snipers and died later. Martin Zozofsky, Ulysses Lingerfelt, James Dell, Vern Johnson, Willie Raleigh, George Miller, and Lawrence Henderson were also killed at Pellingen.”

On to Trier

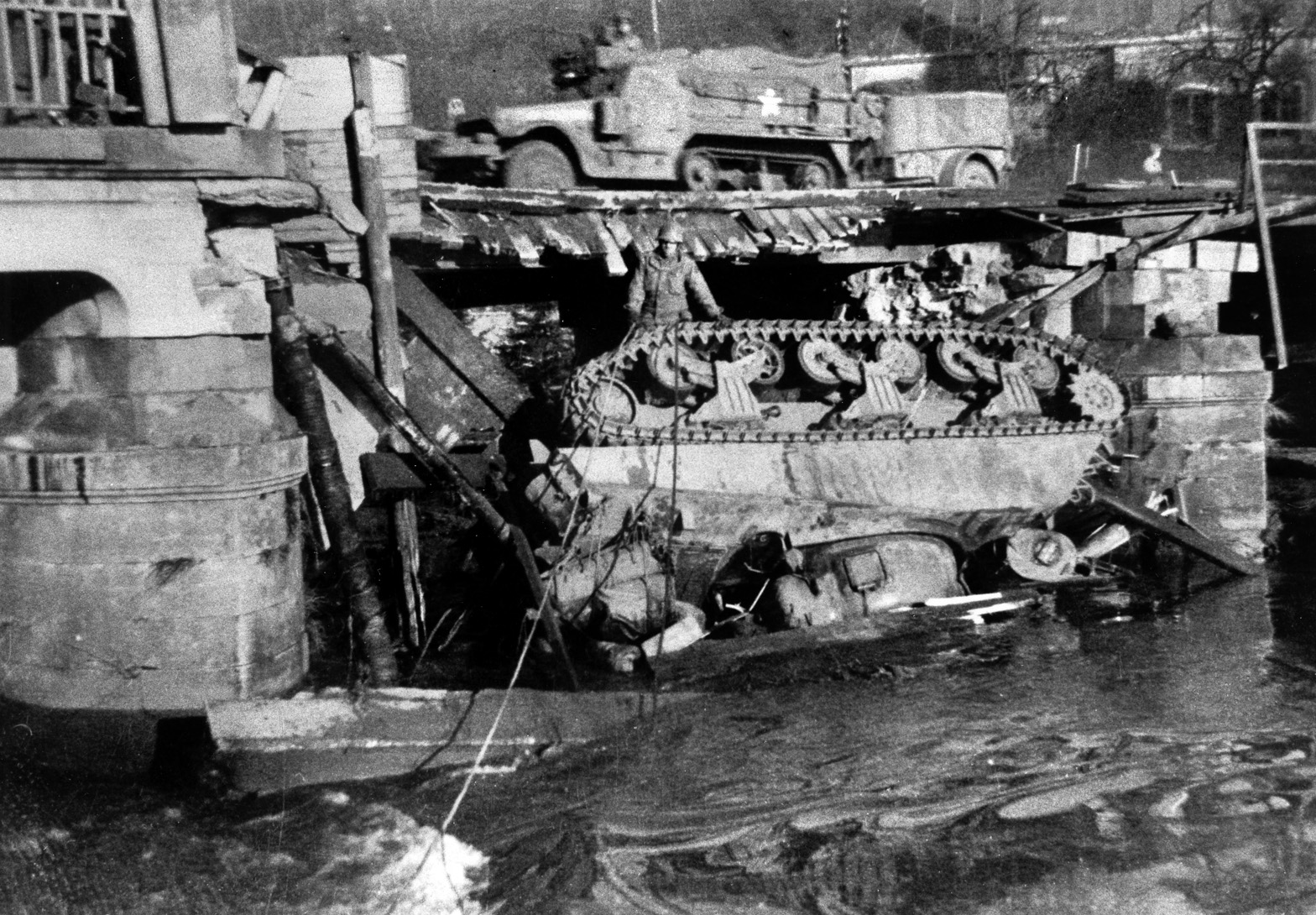

After the opposition at Pellingen was overcome, it was time to head for Trier, a city founded by the Romans over 2,000 years ago. It is said that Trier contains more important Roman remains than any other place in northern Europe. Its most important landmarks are the Porta Nigra arches, built in 275 AD; the piers and buttresses of the bridge over the Mosel River are said to date from 28 BC.

Trier had been subjected to heavy Allied shelling and aerial bombardment for months, and the defenders had no stomach for a fight when the 10th Armored came calling on March 1; after a half-hearted stand, the defenders surrendered.

A Stars and Stripes reporter accompanying the 10th Armored noted, “Attacking with five columns of infantry and tanks, the 10th reached the outskirts of Trier yesterday at noon, and 24 hours later Captain Robert Wilson raised an American flag that his wife had sent him from Newark, N.J., over the Porta Nigra.

“Ignoring snipers, Lt. Col. Jack Richardson … led a task force through the town to take one of the two bridges over the Moselle intact. Lieutenant Wilbur Beadle, Jr., led a force of armor and infantry across the bridge to secure it.

“After the bridge was taken, the 55th Engineers cut all the wires and removed two tons of dynamite from underneath the structure. Then Task Force Richardson turned its attention to clearing the city to the east from the Mosel. More than 800 German troops were scooped up as they came out of the houses in the morning ready to defend a city that had already been overrun.”

The reporter continued: “Richardson’s command post was set up in the center of the city at dawn. Just across the street from the CP, a group of Germans sauntered out of a house to help defend Trier. They, too, were much too late to help.”

A house-to-house search commenced, and 3,000 prisoners were rounded up. General Morris coordinated with the 94th to help occupy the city and evacuate prisoners to the rear.

Once Trier was secure, both Generals Eisenhower and Patton visited the 10th Armored command post. A division historian noted, “Ike’s visit to Trier brought to mind a rumor which had widely circulated. Eisenhower supposedly sent a directive to Patton on March 2. In it, Patton was ordered ‘By-pass Trier to the south … it will take four divisions to capture it.’

“The Third Army commander immediately radioed Eisenhower with the news that he had just taken Trier with one armored division, adding, ‘What the hell do you want me to do—give it back to the bastards?’”

After a four-day rest, it was time to resume the offensive. Morris’ division was ordered to head eastward toward Wittlich, battling stubborn resistance all the way and losing men at places such as Ehrang and Schweich—places that no one had ever heard of before.

Corporal Bob Weber recalled that Ehrang was especially tough. “We attempted crossing the Kyll River into Ehrang on foot after dark but, when we passed in front of a burning house across the river, a machine-gun opened fire on us and we had numerous casualties. Dana Goodwin was killed here.

“We took off to a comparatively safe distance down the street and stayed in a large empty house for the night…. Large caliber—possibly 270mm—guns shelled the street and hit the corner of the house, so we spent the night in the cellar with some civilians. Kenneth Ruth, on guard outside, was knocked down by one blast, but he was OK.”

The next day, March 5, Weber noted, “At 11:00 a.m. we hiked back to the halftracks and started out through the woods again to try crossing farther up the river. That ended badly also as we had mortar and small-arms fire thrown at us all the way down the draw; a bunch of us spent the late afternoon and night in a water tunnel with the creek flowing underfoot. Sgt. Mallick sat down next to me on the bank of the draw and he was hit in the leg by a sniper almost right away. Kenneth Ruth was hit by mortar fragments and he cracked up.”

On the 6th, Weber’s unit again tried crossing the Kyll. “I was so weary I could hardly walk uphill,” he wrote. “Going down the same trail we used the night of the 4th, we caught more small arms and mortar. I could see the bullets strike the rocks nearby. As soon as we reached the clearing between the railroad and the river, the fire ceased to a large extent, though all but two of our rubber boats were sunk and Capt. Eisberg was wounded badly in the leg.”

After crossing the Kyll, the 10th Armored took Wittlich on March 10. The division moved so fast and showed up unexpectedly at so many places that the Germans began calling it “the Ghost Division.”

The remaining enemy holdouts were caught in a vise between Patton’s Third Army in the north and General Alexander Patch’s Seventh Army in the south. On March 14, 1945, the vise began to squeeze the hilly Saar-Palatinate Triangle—with the Germans stuck in the middle.

But the enemy would not give up without a fight. Hitting their opponents with everything they had, the Germans were now fighting on their home turf. The middle of March saw the 10th Armored engaged in one of its fiercest battles since the Bulge.

A division historian wrote, “At night, Tigers trained anti-aircraft searchlights on overhanging clouds to illuminate the battlegrounds. Fighting around the clock, the 10th pushed a 13-mile front 21 miles in three days, stood outside its first objective, St. Wendel.” Although not a major city, St. Wendel was a good-sized town and an important German communications center about 30 miles southeast of Trier.

Going into battle alongside the 10th Armored were two infantry divisions: Maj. Gen. Horace L. McBride’s 80th and Maj. Gen. Willard S. Paul’s 26th.

With Brig. Gen. Edwin W. Piburn’s CCA in the lead, the drive on St. Wendel began at 3:00 a.m. on March 16; Roberts’ CCB followed. Before dawn the next day, elements of the division were fanning out to cross the Blies River and encircle the city from the north.

A division historian wrote, “A few minutes after midnight on March 17, both combat commands struck out in a coordinated assault, utilizing searchlights to light up the battleground. Against very stubborn resistance, the advance was slowed during the day, but by dusk on March 18, Team Cherry managed to reach the outskirts of St. Wendel.

“At this time, the other task forces had knifed their way to within three miles of the city. Teams from Task Force Hankins [Lt. Col. Curtis L.] plowed forward towards the division’s first big objective at St. Wendel. Before they reached that place however, they had to clear Castel.”

Clearing Castel, 10 miles from St. Wendel, proved to be easier said than done. After initially entering the hamlet against little resistance, four panzers suddenly appeared from out of nowhere and quickly knocked out three Shermans. A bazooka team took out three panzers and forced the fourth to flee.

Late that night, large antiaircraft searchlights were switched on, their beams bouncing off the cloud cover and creating what is called “artificial moonlight,” which allowed the 10th Armored to continue its march toward St. Wendel. Then, according to the division historian, “As the column rolled down the road toward St. Wendel, the lead tank almost ran into an enemy anti-tank position. Before the Germans could man their gun, it was knocked out by a well-placed shot.”

The enemy seemed ready and eager to defend St. Wendel, for, as the advance elements of the division approached the city, anti-tank gunners opened up with four powerful 88s and knocked out two Shermans. After being located by a recon unit, the four guns were destroyed.

With the way into the city now cleared, the rest of the 10th Armored rolled in and took St. Wendel against slight opposition. Teams Cherry and Chamberlain (Lt. Col. Thomas C.) roared onward 20 miles to the east in the direction of Kaiserslautern and the Rhine beyond, supported on the flank by Colonel Wade C. Gatchel’s CCR.

One element of the advancing 10th pressed northeast and came across a large Wehrmacht Kaserne (barracks) and training area located at Baumholder; it was overrun with little resistance.

As Baumholder was being captured, the rest of the division rolled onto one of the fabled autobahns and roared past Ramstein and Landstuhl, amazed to find thousands of German soldiers marching west in the grassy median of the divided superhighway, unarmed and waving small white flags.

As the 10th Armored and 80th Infantry Divisions approached the outskirts of Kaiserslautern, an industrial city and Wehrmacht supply center with a pre-war population of some 100,000, they were met by sporadic gunfire but with none of the intensity they were expecting. Kaiserslautern was soon in American hands.

In a tribute to the 80th Infantry Division, which had done the dirty work of mopping up the city, Maj. Gen. Morris insisted that the 80th—not the 10th—be credited with Kaiserslautern’s capture.

From the end of March until the middle of April, the U.S. First (Hodges) and Ninth (Simpson) Armies were engaged in encircling the industrial Ruhr area while, to the south, George Patton’s Third and Patch’s Seventh Armies were knifing toward Boppard, Wiesbaden, Frankfurt-am-Main, Darmstadt, Aschaffenburg, Worms, and Mannheim.

The Armoraiders were directed to take Mannheim on the Rhine and, a few miles beyond, the university town of Heidelberg. Some resistance was met at Mannheim but was quickly overcome, and the wise burghers of Heidelberg declared it an “open city” and surrendered to the 10th Armored and the 63rd Infantry Divisions without a fight.

When the 10th Armored entered Heidelberg to establish its headquarters in the city, most of the townsfolk turned out to cheer the arrival of the Yanks and to strew flowers in their path. Heidelberg was spared the destruction that had befallen many other German towns and cities.

On April 2, the Nazi Party secretary Martin Bormann proclaimed, “National-Socialists, Party Comrades! After the collapse of 1918, we gave ourselves body and soul to the struggle for our national preservation. The hour of greatest danger has now struck. The threat of renewed enslavement calls for our every and final effort. From now on let us resolve to oppose the invader with a remorseless will.

“Provincial and district leaders and other Party officials will carry on the good fight in their own territory, will vanquish or die. Only scoundrels will leave their posts without the Führer’s express orders, will refuse to fight to the last breath. Lift up your courage and stamp out every trace of weakness! The hour allows only one slogan: ‘Victory or Death!’” For many Germans, it would be the latter.

The 10th Armored, 63rd, and 100th Infantry Divisions were directed to head for Heilbronn on the Neckar River—an important supply center for the Wehrmacht and where the Germans were determined to fight. Brig. Gen. Piburn’s CCA and Colonel Roberts’ CCB were in the van of the attack on Heilbronn in early April.

According to the division’s history, “East of Heilbronn, the crack 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division had holed up. While the [U.S.] 100th Infantry Division assaulted the Heilbronn bastion, the ‘Ghost Division’ was 40 miles east of Heilbronn, behind the startled 17th SS, and astride the Nurnberg-Stuttgart highway deep in Germany. In two days, CCA and CCR had engineered one of the division’s most brilliant maneuvers.”

After Heilbronn fell, VI Corps ordered the 10th Armored, along with the 63rd Infantry Division, to leave the mopping up to the 100th Infantry Division and continue southeast for Crailsheim, 40 miles southwest of Nuremberg and 100 miles from Munich.

The French First Army was given orders to take Stuttgart, 25 miles to the south and home to a population of 500,000. Stuttgart was one of Germany’s major industrial cities in the south, where the Porsche tank factory and the Daimler-Benz/Mercedes works were located. The French succeeded.

Patton’s Third Army secured Frankfurt-am-Main on March 29 and headed east into Thuringia where, on April 4, elements of the Army discovered the German national treasury hidden in a salt mine in Merkers and the nearby Ohrdruf and Buchenwald concentration camps a few days later.

Tough Fight for Crailsheim

The 10th Armored Division was about to engage in a three-day fight for Crailsheim, some 45 miles northeast of Stuttgart—one of its most difficult battles of the entire war and the strongest stand by the German Army since the Battle of the Bulge.

After dark on April 5, Task Force Hankins, the advance element, began moving but was slowed by enemy resistance, roadblocks, anti-tank fire, and thick woods that lined both sides of the roads and limited maneuvering capabilities while providing perfect cover for snipers and ambushes.

TF Hankins fought its way into Crailsheim but, as Herbert Stone, a member of the division’s 90th Cavalry Recon Squadron, recalled, “Four German divisions, including an SS panzer division, encircled the town and cut off Hankin’s lifeline from the rest of the 10th…. The Germans controlled several wooded areas on both sides of the road leading into Crailsheim. We were alerted to mount up and lead the charge. This was going to be a turkey shoot and we were the turkeys. The Germans were buried in foxholes on both sides of the road and the troops in open vehicles were most vulnerable.

“The 1st Platoon of C Troop was to lead the charge…. My machine-gun peep was next in line. I was seated in the rear on the right-hand side, crouching as low as I could possibly get and firing my rifle at an unseen enemy hidden on the left side of the road. The soldier on my left was firing the .30-caliber machine gun into the wooded area on the right side of the road. There were times when I could feel the top of my helmet rubbing up against the bottom of the machine-gun barrel. Bullets were flying all around us.”

One of the bullets found its mark in the open peep in front of Stone’s vehicle; a GI was hit and died from loss of blood. Stone said, “He joined our outfit as a replacement for a casualty we incurred at the Battle of the Bulge. He left a wife and two small children.”

Seconds later, a German bullet hit Stone’s rifle while he was firing it and blew it apart. Using a P-38 pistol he had taken off a German officer a week earlier, Stone said that he kept firing into the woods until the weapon jammed. “The only weapon I had left was my bayonet and needless to say, this did not give me a sense of security.”

Bob Weber, A Company, 54th Armored Infantry Battalion, who had just been promoted to staff sergeant, recalled, “Lieutenant McGrath called the squad leaders together saying that 1,000 Heinies had attacked Crailsheim in early morning, cutting us off. Heinie planes were active—they had an airfield only 19 kilometers away—and we were in a hot spot.

“It was at Crailsheim that I saw the first jet-propelled German planes. They were so fast I could hardly keep binoculars on them…. Our column was strafed on the way to Crailsheim and we jumped out of the track and out into the field beside.”

Before dark on April 6, CCA had penetrated the outer defenses of Crailsheim, but the next morning brought difficulties as the defenders refused to give up the city without a fight. As additional 10th Armored forces approached the city, heavy barrages of rockets and artillery smothered them. Then the Luftwaffe swooped in with Me 109s, Me 110s, and Me 262 jets that prevented CCR from reaching and reinforcing CCA. This was followed by ground attacks launched by enemy units brought in by General Hermann Foertsch, German First Army commander, from surrounding areas.

Brig. Gen. Edwin Piburn later commented that at no other time during the war had he seen so many German planes as there were over Crailsheim—a swarm of 325 aircraft; 50 of them were swatted out of the sky by the 10th Armored’s antiaircraft batteries.

Bob Weber recalled, “A Heinie plane came down the street and dropped a bomb nearby, sending plaster crashing down and glass flying.”

“We had two peeps, two halftracks, and a 105mm gun tank. The two peeps led, followed by the half-tracks and then the tank. Just past an intersection on the way out, our convoy was fired on by panzerfausts (anti-tank rockets) from alongside the road on our left. The first shot hit the peep right in front of us square on the left side and the next went over the hood of our track into the field on the right of us.”

One of the men in the peep began firing the machine gun in the general direction of the enemy fire, but, as Weber said, “Whoever had put the machine gun back into its mount had placed a retaining pin in the wrong place and we couldn’t depress the gun below horizontal. I gave the driver, Jim Denton, of the machine-gun squad (our driver, Lowery, was so drunk that we couldn’t rouse him down in the cellar), the order to back up. After we had backed about 100 yards, we rammed into the track behind, which had stalled. In doing so, we damaged our halftrack, bending the body so that it scraped the track.

“We got turned around and went back to Ilshofen. The squad in the stalled track got in with us and the tank crew, I understand, in turning around got bogged down in the mud, had to bury their breech block and walk back to Ilshofen. I reported to the task-force commander, Major Wheeler M. Thackston, that we had been fired on and the crummy guy raked me as though it had been my fault.”

On April 7, General Morris flew to Crailsheim in a Piper Cub plane to reestablish contact with forward elements. A 10th Armored historian wrote, “Prior to this flight, the general ordered Task Force Roberts and the CP of CCA to the Crailsheim area. When he got to Crailsheim, the Tiger Commander sent word to Riley [Lt. Colonel John R. Riley, commanding officer, 21st Tank Battalion] to pass through Hankins and set up a forward CP with Task Force Hankins.

“It was not until late in the morning of April 7 that Riley was able to send Team Felice towards Schwäbisch Hall. On the way it captured Rossfeld. By afternoon, the Force had gone on to take IIshofen and Wolpertshausenn. At Ilshofen, Riley was bombed and strafed by a squadron of Me 109s.”

Once the Armoraiders had battled their way into the heart of the city, the Germans responded with a strong counterpunch, hitting the town with heavy storms of artillery fire and infantry assaults.

To ease supply problems, a fleet of C-47s dropped much-needed food, ammunition, and fuel to Morris’ men. With urban combat taking its toll on the Yanks and a German mountain regiment blocking roads to the northwest—which effectively cut off the division’s supply lifeline, which stretched back to Stuttgart—American fighter planes were called in to bomb and strafe German positions.

Then, on April 8, a sniper outside of Crailsheim killed Colonel Bernard F. Luebberman, the division’s artillery commander. He was the division’s highest-ranking officer killed in the war. The following day, as the Army’s official history said, “A contingent of CCB finally got through with a few supply trucks … but to travel the road to Crailsheim remained a task for the fearless and strong.”

As Americans and Germans battled in the rubble of the smoldering, burning city, a Stars and Stripes reporter wrote, “The fighting at the tip of the Crailsheim finger was the most bitter along the Western Front.”

Another historian said, “Crailsheim was assuming all of the characteristics of another Bastogne.”

At one point in the fighting, Task Force Roberts (Lt. Col. William T.S. Roberts) was advancing when it came under enemy fire. The rear elements of TF Roberts mistakenly headed in the wrong direction, towards Leofels, northwest of Crailsheim. As he rushed to the rear to turn the elements around, Lt. Col. Roberts was killed by a sniper’s bullet.

The loss of Roberts was a blow to everyone. Captain Richard Ulrich, the S-3 and senior remaining commander, was named by Piburn to take over temporary command of the task force. Ultimately, Colonel Basil G. Thayer became the commander.

Suddenly, higher headquarters decided that Crailsheim, once regarded as “vital,” was not worth the bloodletting and so, on April 11, ordered Morris’ division to pull out of what was now deemed an “unimportant” city. The withdrawal was a jagged pill for the proud Armoraiders to swallow.

Dwayne Engle, son of an Armoraider, noted, “Even though the city had been relinquished to the Germans and 10th Armored losses were heavy, we had managed to capture 2,000 German soldiers, kill more than 1,000, shoot down 50 valuable German aircraft, and divert large numbers of German troops.”

With the battle for Crailsheim ended, Brooks’ VI Corps ordered the division to head back west and assist the 63rd and 100th Infantry Divisions that were still engaged at Heilbronn.

On Thursday, April 12, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt died of a cerebral hemorrhage. The next day, Hitler, buoyed by the news of FDR’s death, proclaimed, “Berlin will remain German. Vienna will be German again.”

While returning to Heilbronn, the 10th Armored ran into stiff resistance by Hitler Youth and old men who had formed a unit of the Volksturm at Öhringen, a small city between Crailsheim and Heilbronn. It took a concentrated barrage of “time on target” artillery fire to subdue the fanatical defenders, and resistance in the city collapsed on April 13.

Eighteen-year-old Richard W. “Dick” Abraham, of the 10th Armored’s C Company, 61st Armored Infantry Battalion, recalled arriving at Öhringen: “The next morning was an intense period that involved crossing a field under continual mortar shelling. One of the casualties was a man several paces behind me…. We secured the village that was the source of the mortar fire and waited for our halftracks to join us.

“My recollections of the next few days are very slim. We slept on the halftrack as they covered great distances and only awoke when stopped for refueling, isolated small-arms fire, or roadblocks. If the small-arms fire or roadblocks were serious, we would dismount, set up the .30-caliber, and return the fire.”

The division then continued west to Heilbronn to assist in subduing the holdouts there.

Now, in the final, heady weeks of the war, with the scent of spring flowers and victory in the air, German resistance was crumbling and sporadic. In many of the towns and villages a profusion of white bed sheets—in violation of the Nazi government’s prohibitions—fluttered from windows and balconies, signaling surrender, while in others, fanatical Germans set up roadblocks and barricades to slow the Allied advance. Snipers took up positions in church steeples or upper-story windows and waited for their prey to march into view, knowing that their stand would be their last.

One historian noted, “American troops had a simple rule: if a town showed white flags and offered no resistance, they rolled through peacefully. If American troops came under fire, they smashed the community.”

The Third Reich was now in a state of collapse; the Russians had reached Berlin, the British closed in on Hamburg, Hodges’ First and Simpson’s Ninth Armies neared the Elbe facing Berlin, and Patton’s Third Army entered Czechoslovakia.

The Battle for Ulm

Now came orders for Alexander Patch’s Seventh U.S. Army, to which the 10th Armored had been attached on April 8, to drive southward toward the Danube and the Bavarian Alps, block the mountain passes into Austria, and seize the Brenner Pass-Innsbruck area. Ulm was in the way.

The 10th Armored historian wrote, “Task Force Hankins joined Thackston’s unit and both were assigned to the Reserve Command, which was now pushing northeast to assist the 44th Infantry Division at Ulm.”

On April 23, three days after Hitler celebrated his 56th birthday in his besieged Berlin bunker, the 10th Armored Division reached the outskirts of Ulm—about 40 miles southeast of Stuttgart, and the site of one of the last urban battles of World War II.

The next morning, TF Hankins fought its way into Ulm, regarded in the 14th century as one of the world’s great trading centers, before in the ensuing centuries its power diminished.

Until 1945, Ulm, the charming city on the Danube in the southwest German state of Baden-Württemberg, was famous for two things. First, in the fall of 1805, the French Leader Napoleon Bonaparte and his Grande Armee of 210,000 men defeated a 72,000-man Austrian Army here.

Second, Ulm was, and is, home to the Ulm Cathedral (known as Ulm Minster)—at 530 feet the tallest building in the world until the 20th century. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart played its organ in 1763, and Albert Einstein was born in the city in 1879.

(Ulm has another historical connection: Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s state funeral was held in the city on October 18, 1944. He had been coerced into committing suicide when it became known that he had had some knowledge of the assassination attempt on Hitler’s life on June 30, 1944. Rommel was buried in Herrlingen, west of Ulm. His grave is still decorated by admirers.)

Ulm’s 92,000 citizens had luckily avoided destruction at the hands of the American and British air forces. But her luck ran out on December 17, 1944, when an RAF raid saturated the city center with 1,449 tons of bombs.

The primary targets were of military significance: two truck factories (Magirus-Deutz and Kässbohrer) that supplied vehicles for the Wehrmacht, along with other industrial firms and the railroad marshaling yards. But the bombs also fell into the city’s historic center.

Over 700 people died in the bombing, with 613 wounded and 25,000 civilians left homeless. Two more U.S. and RAF raids—on March 1 and April 19, 1945—caused more deaths and damage: 632 killed and over 80 percent of the city center destroyed. As with Cologne, the bombs spared the medieval cathedral but left much of the rest of Ulm in ruins.

As the 10th Armored closed in on Ulm, Bob Weber said that his unit was taking hundreds of prisoners and that he saw “a gallows erected to the right of the road and a body with a sign pinned on it was swinging from the crossbar. It was reported to be a German who had refused to fight and was executed by the SS.”

Patch’s Seventh Army plunged like a bayonet into the heart of the Tyrol and Bavaria. On the right flank was Brooks’ VI Corps, in the center was Maj. Gen. Frank W. Milburn’s XXI Corps and on the left was Maj. Gen. Wade H. Haislip’s XV Corps.

Maj. Gen. Morris sent his recon units dashing to the Danube to find any bridges between Ulm and Ehingen that might be suitable for his armored units to cross. The 44th Infantry Division was assigned to support the Tigers in their drive.

Soon the 10th Armored was positioned along the north bank of the Danube southwest of Ulm. Combat Commands A and B captured three bridges intact and, before midnight, crossings were made.

The 10th Armored’s history: “At 0700 on April 25, Connolly [Captain Bernard Connolly, Company A, 3rd Tank Battalion] abruptly altered his direction of attack when he was informed that four other attacking columns, including part of a French armored division, had been stopped by strong enemy anti-tank fire, and proceeded to Grittelfinger, located less than two miles from Ulm.”

Looking down on Ulm from a nearby hill, Connelly devised a plan of action. Leading his team across an enemy-defended mine field, Connelly, with five Sherman tanks in the lead, dove into the western part of the city, taking 600 stunned Germans prisoner in the process. Shortly thereafter, a German battalion commander sent word that he wished to surrender his 900 men.

With the western part of Ulm now in American hands, resistance in that portion of the city ceased, and the Armoraiders spread out to encircle Ulm and cut off escape routes. The situation became somewhat confused when a contingent of French troops showed up, but soon the mess was untangled.

On April 25, a war correspondent noted, “The fighting 10th Armored Division in the past 48 hours has captured an estimated 1,200 prisoners and taken 40 towns. The big news of the day comes from Task Force Hankins, currently ‘reducing’ resistance in the city of Ulm. Hankins reports that it was Team Connolly who first entered Ulm yesterday morning at 0854.”

The communiqué continued, “On April 26, the 44th Infantry took charge of the situation at Ulm permitting [three] Task Forces to join the chase to the south and east. Pushing ahead with violent effectiveness now were the 10th’s three major battle commands. As they streamed southward to the Memmingen-Mindelheim- Landsberg line, they were egged on by Maj. Gen. Brooks who declared, ‘Push on and push hard—this is a pursuit, not an attack.’

“The Tigers reached fantastic speeds of more than 30 miles a day during the rout and at the same time managed to gobble up 9,000 prisoners. Along the way, undermanned strong points were destroyed by fire and the enemy’s vehicles wrecked. Huge enemy groups were shipped to the rear in never-ending truckloads. During this period, the Tigers of Task Force Hankins overran a carefully camouflaged airfield and sharpened their aim as they picked off German jets as they attempted to take off.”

On April 26, with Ulm secured, the rest of VI Corps troops crossed the Danube and began a mad dash into the Tyrolean Alps and all the way to the Brenner Pass at Innsbruck, Austria.

On that same day, the Armoraiders reached Memmingen, site of a Nazi concentration camp. “I think it was a work camp, not a death camp,” said Robert Anderson of the 10th Armored’s 150th Signal Company. “I’m sure people died right and left, but it was a work camp. That was my first experience seeing people with the striped uniforms…. They must have been from Russia or something like that, but there were a lot of people that didn’t look like Germans or like us Caucasians. They were obviously from a different ethnic group. They were wearing the striped uniforms, milling around and so on. [Our officers] didn’t want us to have any contact with them.”

The next day, the Tigers liberated the Landsberg concentration and displaced-persons camp, a sub-camp of Dachau.

10th Armored units were the spearheads into the mountain passes, picking up more of the surrendering enemy as they went. Following the armor were the 44th and 103rd Infantry Divisions that protected the 10th’s flanks and helped to smash the last remnants of General Erich Brandenberg’s Nineteenth German Army in the south.

A historian wrote, “Seventh Army’s 10th Armored Division took 28 towns in a single day on 23 April. By April 27, both the Seventh and Third Armies had crossed the Danube, and Ulm, Augsburg, and Regensburg were in their hands.” The U.S. Army’s official history of the war noted, “Ulm, for its size the most heavily bombed city in the south, was a ruin. Water-filled bomb craters covered blocks where factories and houses had once stood. The streets were rough paths through the rubble. But the 500-year-old Gothic cathedral still stood, towering above the flattened city around it.”

At the end of April, the 10th Armored came across and liberated almost 4,000 Allied prisoners of war from a POW camp, then continued on to occupy Oberammergau and Garmisch-Partenkirchen. A task force crossed from Füssen into Austria—the first Seventh Army unit to enter Hitler’s homeland. At this point, the war for the Seventh Army and the 10th Armored Division ended.

During its eight months in combat, the 10th Armored had compiled a sterling record. The Tigers had traveled 600 miles through five countries, seized 410 towns and cities, and taken 56,000 prisoners. When hostilities finally ended on May 7, the division had lost 951 men killed and had 3,109 wounded.

The Tigers were inactivated on October 13, 1945, but their spirit never disappeared.

The author wishes to thank Craig Charlton, Webmaster, 10th Armored “Tiger” Division Veterans Association and son of veteran Reginald “Reggie” Charlton, for his assistance with this article.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments