By Eric Niderost

It was the middle of June 1191, and the Third Crusade was bogged down before the walls of Acre, the largest city and chief port of the former Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Its recapture from Muslim forces was essential. Final victory might well be achieved, but only if its stout walls and stubborn defenders could be overcome.

The Crusaders were in a sorry state, a position made worse by the fact that the besiegers were themselves besieged. A powerful Muslim army composed of Turks, Nubians, Mamlukes and others had come to rescue the garrison and break the Christian stranglehold, and though they failed to raise the siege, their presence was a constant reminder of how fragile the Crusader position was. The Muslim army was led by the Sultan of Egypt, a dynamic man named Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn-Ayyub. Better known to the Crusaders as Saladin, he was a powerful adversary.

Occasionally the Muslims scored a local success, and sometimes the Crusaders gained the upper hand, but such changes of fortune were temporary. The stalemate dragged on, month after interminable month, with seemingly no end in sight. Sanitation was poor in the Middle Ages, and before long the Crusader camp became a fetid bog of dirt, squalor and disease. Sickness became rife, as typhus and other ills swept through the camp like biblical plagues. Probably more Crusaders died of disease than in battle with the Muslims.

The winter of 1190-1191 was the absolute nadir of Crusader fortunes at Acre. Supplies were low, and famine was added to a growing list of woes. Even feudal magnates and prominent knights were reduced to eating their horses, a measure of extreme desperation. A knight was by definition a warrior on horseback, and without a mount a knight’s effectiveness and prestige were literally and figuratively lowered. When horses were butchered, salivating crowds gathered in hopes of obtaining a slice; even entrails were eagerly sought after. Bread was similarly scarce; it was said a one-penny loaf fetched prices as high as 60 shillings.

Reinforcements on the Way

By the summer of 1191 the Crusaders had weathered the immediate crisis, and periodic supplies and reinforcements from overseas helped them hang on. The clammy cold and driving rains of winter were replaced by the furnace-like heat of a Middle Eastern summer. Only one thought sustained the Crusaders in these difficult weeks: the imminent arrival of Richard I of England. Richard, surnamed Coeur de Lion or “Lionheart,” was the foremost warrior of his age, a man whose skills at arms, talents in siegecraft and prowess on the battlefield made him a legend in his own time. Already a great feudal lord, when he took the Cross and became a Crusader he became a Christi Miles, a “Knight of Christ.” Who could doubt the Crusade’s ultimate success?

On Saturday, June 8, 1191, a fleet of galleys appeared offshore, and news of their arrival spread throughout the Crusader camp. Richard had arrived! The galleys made a brave show, banners and pennants floating high above billowing sails, oars rising and falling in unison as they churned the placid Mediterranean into a white-flecked foam. Richard was aboard his war galley, and as distance shortened, the king was able to see his objective clearly. Acre itself was impressive, with high towers linked by stout, thick walls. Crusader siege engines had done much damage, but clearly there was even more work to be done. He could see the siege lines, and the squalid Crusader camp, but what lay beyond really caught his eye. Past the immediate environs of Acre, Richard gazed at “the hill peaks and the mountains and the valleys and the plains, covered with the tents of Saladin and Safadin [Saladin’s brother] and their troops, pressing hard on our Christian host.”

When Richard landed he was greeted by King Philip Augustus of France and a host of other feudal lords, political animosities momentarily forgotten in the euphoria of the moment. The disappointments and privations of the past also seemed erased as trumpets blared in salute and bonfires illuminated the night sky. Richard also brought fresh troops, supplies and siege engines, welcome additions to the overall effort.

Christian West vs. Muslim East

The Third Crusade was part of the ongoing struggle between the Christian West and Muslim East for possession of the Holy Land. The ancient city of Jerusalem was a particular bone of contention among warring faiths. To Christians, Jerusalem was associated with Jesus Christ, the scene of his ministry, death and resurrection. Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre was one of Christendom’s most sacred places, covering the sites of Jesus’ Crucifixion and tomb. To Muslims, Jerusalem was the third-holiest city after Mecca and Medina, the place where the Prophet Mohammed himself ascended into heaven.

In 1099 the First Crusade conquered Jerusalem from the Muslim Turks and established a series of feudal entities called the “Crusader States.” The largest and most important of these was the Kingdom of Jerusalem, roughly corresponding to today’s Israel and parts of Lebanon and Jordan. The Western Europeans who lived in the Middle East were variously called “Franks” or “Latins,” the latter title because they espoused Roman Catholic Christianity. To the Muslims the Crusaders were unbelievers and infidels, and to the Crusaders the Muslims were “Saracen” dogs and “base cattle.”

The Crusader States were alien enclaves in a largely Muslim world, so constant vigilance was necessary. To most Europeans the Holy Land wasOutremer, or “overseas,” a name that conjures images of isolation and remoteness. Two military orders, the Templars and Hospitallers, became the twin pillars of the Kingdom of Jersusalem. The Templars, more formally the Poor Knights of the Temple of Solomon, were incorporated in 1119. They were warrior monks, pledged to chastity, obedience, and prayer in peace but willing to take up the sword in times of war. The Templars were distinguished by white mantles emblazoned with a red cross. The Knights of St. John of the Hospital, or Hospitallers, originally ran inns and hospitals for wayfaring pilgrims, a function they continued even after becoming a military order.

Internal dissention plagued the Muslim states for years, but under the Kurdish general Saladin unity had been achieved. Saladin’s empire had commercial ties to the Crusader States, and the Sultan, a generally tolerant man for the time, was content to trade with the Franks as long as they honored their treaties. Things changed when a kind of coup made Guy of Lusignan King of Jerusalem in 1186. Vacillating and spineless, Guy depended on the support of powerfulOutremer magnates like Reginald of Chatillon. Unfortunately Reginald was a lawless adventurer who attacked Muslim caravans and killed with impunity.

Goaded by Reginald’s outrages, and frustrated by the fact that King Guy was unable or unwilling to bring his “overmighty” vassal to heel, Saladin invaded the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Guy’s feudal host met disaster at Hattin, a Muslim victory so complete it shook the Kingdom of Jerusalem to its very foundations. Saladin, his anger roused, executed about two hundred Templars and Hospitallers taken prisoner at Hattin, on the grounds they were the “firebrands of the Franks.”

Jerusalem Falls

Jerusalem fell to Saladin in October of 1187, an event that sent shock waves across the sea to Europe and set off a train of events that led to the formation of the Third Crusade. King Guy had stripped his castles of their garrisons to augment his field army, a serious error in judgment. After the disaster at Hattin these castles were easy prey, their skeleton garrisons unable to mount an adequate defense. One by one the fortresses fell to Saladin, and with their capture the Kingdom of Jerusalem seemed on the brink of extinction.

Soon only Tyre remained, a heavily fortified seaport. Saladin’s generals urged him to take the city without delay, explaining it was “the only arrow left in the quiver of the infidels.” It was September 1187, and Saladin could have marched on Tyre or Jerusalem. The Sultan chose Jerusalem, understandable under the circumstances, but it was a decision he would later have cause to regret. The delay enabled a new leader, Conrad of Montferrat, to put Tyre’s defenses in order and instill fresh heart in its citizens. When Saladin did arrive in November of 1187 his siege was unsuccessful. Tyre was a Christian toehold inOutremer, a beachhead that could expand when fresh Crusader armies arrived.

King Guy had been taken at Hattin, but Saladin released the fallen monarch after a short captivity. Perhaps the Sultan pitied Guy and thought of him as a broken reed incapable of further harm. It was to prove another major miscalculation on Saladin’s part. When Guy of Lusignan arrived at Tyre he found Conrad of Montferrat had gained a large following. It seemed most people preferred a resourceful hero (at least in their eyes) over a discredited king. Indeed, the heavy wine of success had gone to Conrad’s head, and before long he nursed ambitions of replacing Guy as King of Jerusalem.

Conrad’s bid was helped by the fact Guy’s claim to the throne was as weak as his character. He had become King only because he had married the heiress to the kingdom. In any case the circumstances of the original coup left a telltale odor of usurper that clung to him. The dubious circumstances of his rise to power, coupled with his defeat at the hands of Saladin, left a political stench around the man that the trappings of royalty could mask but not entirely eliminate.

Yet Guy, who was being written off as an incompetent cipher, suddenly showed some initiative by gathering a small army and marching on Acre. Guy seemed to have no hope of taking the heavily fortified port with the pitifully weak forces he then had at his command. In fact, the march seemed an act of rashness that bordered on insanity. Yet, against all odds, Guy’s siege of Acre continued winning him a begrudging admiration from many quarters. Reinforcements trickled in, until Guy was able to block off Acre’s landward side. Acre became a rallying point, important because it was the first real offensive action after a string of disasters.

Calls for Crusade

In Europe the news of Jerusalem’s fall to the “Saracens” produced outpourings of outrage and dismay, followed quickly by pledges to go on Crusade. Count Richard of Poitou, heir to the English throne, took the Cross, as did Emperor Frederick Barbarossa and Philip of France. Old Emperor Frederick Barbarossa managed to raise a huge army, perhaps 30,000 men or more, but he drowned en route to the Holy Land. Most of his men returned to Germany, though a small remnant—perhaps a thousand—joined the forces besieging Acre.

There were the inevitable delays, including a brief rebellion that pitted Richard against his ailing father, Henry II, but by 1190 the Third Crusade was on its way to becoming a reality. By this time Richard was King of England, having succeeded his father in 1189. Philip and Richard met at Vezelay, then went south to take ship at Marseilles and Genoa forOutremer. The two monarchs wintered in Sicily, then continued the rest of their journey to the east. Philip sailed directly to the Holy Land, but Richard suffered a storm and was delayed by his conquest of the island of Cyprus.

Once Richard arrived in Acre it was naturally assumed by most parties he would take over supreme command. Knights flocked to his banner, adding to his personal army, and common soldiers idolized him as a true warrior king. He certainly looked the part. He was tall, with long, muscular arms that could deliver a powerful sword or axe stroke. It was said that he was “graceful in figure, his hair between red and auburn.”

When fully girded for battle, Richard’s titian-colored locks would be hidden under a coif, or mail hood, which was laced to a hauberk. This was a shirt of mail, consisting of interlaced metal rings that protected torso and thighs. Legs and feet would also be encased in mail, and Richard’s strong hands would be covered with mail mittens.

Not everything was mail; breeches would be worn, and a gambison, or undershirt, would be donned to protect skin against chafing. Richard probably had a surcoat, or sleeveless tunic, that was worn over the hauberk. The surcoat was sometimes dyed in distinctive personal colors, in a kind of nascent heraldic display. There is some dispute over the function of a surcoat; some authorities say it was a way to display one’s heraldic devices, while others maintain it protected the hauberk from the intense rays of the sun.

In any case, Lionheart would use a couched lance for initial attack while mounted on horseback, then switch to sword or axe for hand-to-hand fighting. The King’s shield probably bore his distinctive arms: three golden lions on a red field. The design would later be adopted as the arms of England.

Not long after his arrival Richard came down with “Arnaldia,” a poorly defined disease that was the scourge of the Crusader camp. Medieval diet was poor to begin with, and siege conditions made things worse. Lacking vitamins and essential nutrients lowered resistance to disease. It seems that “Arnaldia” caused its victims to cough and lose their teeth (some accounts say hair and nails). Richard’s grave illness was a major setback for the Crusade, but his relative youth (34) and his prodigious strength pulled him through.

Major Turning Point

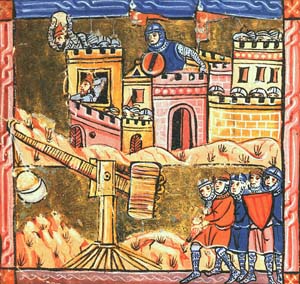

The English King’s arrival was a major turning point, and under his watchful eye siege operations quickened. A variety of siege engines battered Acre’s walls, including a mangonel the French Crusaders dubbed Malvoisin or “Bad Neighbor.” Richard constructed his own mangonels, which were catapults that could lob stones some 1,300 feet. Once released, a stone would fly through the air in a low arc, smashing against a wall with a loud and shattering crash. Sometimes stones would leave huge crater-like dents in the wall, richly veined with fissures and cracks. Sooner or later the wall would be so weakened it would tumble down and be reduced to a pile of broken masonry.

A mangonel was only as good as the ammunition it used. Round, sturdy boulders were highly prized as missile weapons. Richard actually “imported” some of his mangonel boulders; Cyprus quarries were the source of some, and one, a huge boulder mined in Sicily, was said to be so effective it crushed 20 Saracens on impact. The Crusaders also mined under walls, a standard technique of siege warfare. Once a tunnel was dug, the lumber used to shore up the excavation would be fired. When the timbers and tunnel collapsed, so did the wall immediately above—or so went the theory.

At one point Crusaders burrowing under Acre’s wall suddenly ran into a Muslim counter-mine being dug with Christian prisoner labor. In the ensuing underground confrontation, the Christian prisoners managed to make their escape, though the Muslims managed to seal off the Crusader tunnel. Siege towers were also constructed, great wooden monsters that soon loomed over the battered remains of Acre’s once-proud defenses.

A climax of sorts came when Acre’s Maledicta Tower was finally collapsed. Maledicta Tower was a soaring pile of masonry that dwarfed the Crusaders who collected at its base trying to bring it down. The sweating Christians nibbled away at its base, prying out stones with picks and even bare hands, all the while subjected to arrow fire from above. The work was so hazardous King Richard offered a reward of two, three and then finally four bezants (gold coins used in Byzantium) for each stone removed. To set an example, Lionheart himself joined the demolition work, manhandling masonry while arrows zipped by his massive frame. Muslim archers even hung from their feet to get a better shot at the toilers, but to no avail.

Victory at Acre

The end was in sight. To communicate with Saladin the Acre garrison used drums, their throbbing tattoos conveying a note of desperate urgency. Smoke signals were also employed, as were carrier pigeons, but in spite of their pleas the Sultan could do nothing. Acre fell in July 1191, about a month after Richard’s arrival. The Muslim garrison at Acre accepted all of the Christian terms of surrender, which were admittedly harsh.

The True Cross was to be turned over (it had been captured at Hattin), and 1,600 Christian prisoners were to be released. There was also to be a payment of 200,000 bezants to Richard and Philip, and a further 40,000 bezants to Conrad of Montferrat. The Muslim garrison would be held captive until the fulfillment of all the terms.

The long siege of Acre had given the multinational Crusader army a sense of purpose, unifying them in a common effort. But once the prize was taken, political rivalries and personal ambitions came to the surface, threatening fragile unity. The King Guy-Conrad of Montferrat rivalry came to a head, splitting the Crusade into rival and mutually antagonistic camps.

Richard the Lionheart supported Guy’s claims, though he probably had little taste for the man himself. Guy’s wife was not only the heiress of the Kingdom of Jerusalem; her family was a junior branch of Richard’s own House of Anjou. For family as well as feudal reasons Richard had to support Guy, even though the man was related by marriage, and not blood. Besides, Philip Augustus supported Conrad of Montferrat, who was the French King’s kinsman. Richard and Philip were rivals back home, and they weren’t about to change on Crusade.

Eventually a deal was struck that smoothed troubled waters and allowed the Third Crusade to continue. Guy would remain King for life, but after his passing, the crown would fall to Conrad of Montferrat. Conrad’s own claim was strengthened by his marriage to Isabella, Sibylla’s younger sister. Ironically Conrad’s union to Isabella was bigamous, since it was rumored he had one or even two wives elsewhere. Such unpleasant facts were quickly swept under the rug, however, and everyone for the moment was satisfied.

The King of France left Acre for Tyre on July 31, and sailed for home on August 3. More Machiavellian politician than warrior king, the rigors of camp life were not to Philip’s taste. The fall of Acre released him from his Crusader vow—or so he chose to think. Richard was probably happy to see him go, though well aware that once back in France the inveterate schemer might stir up trouble or even try to seize some lands.

Richard Weighs His Options

In any case Richard was eager to resume the campaign against Saladin. He was restless by nature, and besides, Acre had too many temptations for his weary men. The port was full of women of easy virtue, whose siren-like enticements and exotic allure were too much even for the most moral of Crusaders. Saladin’s secretary Imad-ad-Din wrote with salacious delight about these prostitutes, describing them as “tinted and painted, desirable and appetizing.” Warming to his subject, Imad-ad Din graphically describes how the women “made themselves targets for men’s darts, offered themselves to the lance’s blows, made javelins rise toward shields, guided pens to inkwells, swords to scabbards.”

The King of England now pondered his strategic options. Jerusalem was the prize of prizes, its recapture the very reason for the Crusade. But Richard was shrewd enough not to march directly to the Holy City from Acre. The inland route was long and arduous, the terrain rough and hilly. It was already mid-August, and the Galilean hills would be an arid wasteland this time of year. Temperatures were soaring on the coast; how much hotter would they be inland? Water would be at a premium, and there was always the threat that the Muslims would poison the wells.

The idea of marching through a desiccated wilderness was not to Richard’s taste. Besides, it conjured memories of Hattin, where lack of water contributed to the Christian defeat. On the other hand Acre was a secure base, well supplied by ships from Europe. But if he marched directly to Jerusalem, supply would be a logistical nightmare. Richard opted to go south to Jaffa. Once Jaffa was secured, he might proceed even farther south to Ascalon. Once in control of the coast the Crusader base would be broadened, an attractive consideration. Also, the farther south Richard marched, the nearer he came to Egypt, Saladin’s power base. Even if the Crusaders didn’t invade the land of the Nile, the Sultan might be kept off balance by the mere threat of such a move.

But before he could depart there was a nagging problem that needed to be addressed, namely what to do with the three thousand Muslim prisoners taken at Acre. When Richard moved south he would have to detach a substantial force to guard them. This was unacceptable, since the Crusaders were outnumbered and every man was needed for the field army. What happened next was controversial and has become a subject of intense debate among scholars to this day.

Supposedly Richard and Saladin had agreed the Sultan could ransom the Acre garrison in a series of installments, the first payment due August 20. When August 20 came and no money was forthcoming, it was said Richard flew into a rage. Accounts differ, but supposedly the English King felt Saladin was deliberately dragging his feet. By noon of August 20 Richard had had enough. He was going to set an example, and give the Muslims a salutary lesson they would never forget. The three thousand prisoners were led out, hands tightly bound, and walked through a gauntlet of waiting Crusaders. Suddenly the Franks fell on the captives, stabbing, rending and decapitating until all were slaughtered like cattle.

The butchered prisoners lay in spreading pools of blood, a crimson stain that polluted the field and darkened Richard’s reputation. In general the Crusaders applauded the deed; after all, the Saracens were infidels and merited death. Ambroise, whose “Crusade of Richard Lion-Heart” is a major primary source, notes the Muslim prisoners were “slaughtered every one, For this be the Creator blessed!” Predictably the Muslims felt it was the work of the devil, not the Supreme Deity. A Muslim writer declared that the Acre prisoners had been pre-ordained by God “to martyrdom that day.”

March to Jaffa

Whatever the controversy surrounding the execution of helpless prisoners, in the short term the Crusade could now march on Jaffa without further delay. Richard the Lionheart’s army left Acre on August 23, 1191 (some sources say August 22), following an old Roman coastal road south. Even though they were near the coast temperatures were high, so Richard made sure progress was made in easy stages. It was said the Crusaders traveled mainly in the morning hours, before the main heat of the day, and rested in the afternoon. Even so, the hot weather must have been almost unbearable to men encased in chain mail.

If the massacre of the Acre garrison shows Richard at his worst, the march to Jaffa shows him at his best. The King of England was no mere bullying warrior but a charismatic and gifted leader who had genuine military talent. Lionheart opted for a “layered” defense that combined geography and the Crusader’s inherent strengths to full advantage. The army trekked south with the Mediterranean on its right flank, and the toiling troops must have been reassured by the sight of the Crusader fleet that sailed in escort just offshore.

The baggage train marched closest to the water’s edge, and thus farthest away from Saladin’s shadowing army that lurked in the coastal hills. Next came the mounted knights arrayed in three divisions, then the foot-slogging infantry. Since the foot soldiers were the outermost ring of defense along the line of march, they bore the brunt of Saladin’s harassing, probing attacks. Richard made sure that the van and the rear guard were taken by the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitallers, and that they exchanged roles every other day. Their experience with fighting Muslims and intimate knowledge of the terrain made them naturals for such exposed and vulnerable positions.

The baggage train marched closest to the water’s edge, and thus farthest away from Saladin’s shadowing army that lurked in the coastal hills. Next came the mounted knights arrayed in three divisions, then the foot-slogging infantry. Since the foot soldiers were the outermost ring of defense along the line of march, they bore the brunt of Saladin’s harassing, probing attacks. Richard made sure that the van and the rear guard were taken by the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitallers, and that they exchanged roles every other day. Their experience with fighting Muslims and intimate knowledge of the terrain made them naturals for such exposed and vulnerable positions.

The baggage train was important, but the “layered” defense was primarily for the protection of the mounted knights. The knights were the Crusade’s most powerful offensive weapon; when mounted and charging at full gallop they were invincible. As valued “shock troops” of Richard’s army they had to be protected until the right moment, a job that naturally fell to the infantry. The foot soldiers provided a buffer between the knights and the enemy, a defensive “cocoon” that could absorb much punishment.

Saladin and his army continued to shadow the Crusaders, marching on a parallel route some two miles inland. The sultan was basically biding his time, waiting to strike. Medieval armies lacked discipline, and sooner or later the Crusaders would become so disordered they would be open to attack. That, at least, is what Saladin hoped, but to his apparent surprise the Crusaders maintained a steady marching order.

The Ultimate Test of Endurance

The trek south was a test of endurance that few Crusaders would ever forget. The sun was a fiery orb that seemed to hang motionless in the azure vault of the sky, scorching man and beast alike beneath its merciless rays. Rivulets of sweat left white trails through grimy faces, lips swelled and blistered with thirst, and hauberks became torturous mantles of blazing hot metal. There were few pack animals, so much of the baggage was carried by foot soldiers on a rotation basis. On one day half the infantry would guard the outer perimeter of the march, fending off Muslim attacks, while the other would carry the baggage. The next day, their positions would be reversed.

Muscles ached from their burdens, and even legs accustomed to walking must have found trudging through shifting beach sands trying. The knights rode their horses, but they too suffered in the torrid August sun. Hair matted with sweat under mail coifs, half-suffocated by the heat and the labor of wearing 40-pound hauberks, the knights paid for their elite status.

Dehydrated and weary, the Crusaders began to come down with sunstroke. Richard saw to it that victims were transferred to waiting offshore vessels to recover; those that succumbed were buried in the sands. Above all, Saladin must never be aware of how hardships were decimating the Crusader army. From time to time the Sultan would launch probing, hit-and-run attacks on the Crusader column, which was stretched out for several miles. Swarms of Turkish horse archers would suddenly appear mounted on swift ponies, filling the air with stinging shafts before retiring into the hills. At one point early in the march the Crusader rear guard was almost cut off and might have been annihilated, but Richard and a force of knights literally came to the rescue.

It seemed that Richard’s army could find no peace. Evening brought a respite from the oven-like heat, but when the exhausted Crusaders bedded down for the night they found they were confronted with a new host of enemies. One campsite was alive with “swarms of tarantulas and stinging worms” that crawled under tunics and over legs and inflicted painful bites on exposed flesh. Although the arachnid onslaught was crushed underfoot, it looked as if the Crusaders were outnumbered and outmaneuvered by the eight-legged creatures. Then, in sheer desperation, the men began to raise a clamor by beating on pots, kettles, shields and anything else that could make a noise. The ear-splitting cacophony seemed to work, driving the spiders away and allowing the Crusaders to snatch a few hours of rest.

The march continued, mile after toilsome mile. The route took the Franks inland for a time, past the ridge of Carmel then back to the sea again at Athlit. The Crusaders had to ford several rivers, and one stream near Caesarea seemed particularly cool and inviting after the rigors of a long, hot journey. Two knights removed armor and tunics and bathed in the waters, only to be devoured by waiting crocodiles. The Crusade dubbed the fatal waterway “River of Crocodiles” after the incident.

In spite of the hardships, clergy were on hand to remind the Crusaders they were on a holy mission. Every night a priest would shout “Sanctum Sepulchrum Adjuva,” or “Help us, O Holy Sepulchre!” The impassioned cry would be taken up by the entire Crusade, thousands of voices merging into a mighty chorus of piety and supplication. Twice more the priest would implore the aid of the Almighty, and twice more the whole Crusade would repeat the phrase with a roar that reverberated through the night. In the meantime Saladin was experiencing a growing frustration. Turkish horse archers continued to launch clouds of arrows at the Crusaders, but the latter refused to rise to the bait.

The Muslims were masters of exploiting the weaknesses of their opponents, often using the element of surprise. Individuals as well as armies were also at risk. At Acre a knight was attacked by a Turkish horseman while squatting to relieve himself. Ambroise commented, “It was most cowardly and base, To take a knight thus unaware, While occupied in such affair.” When his comrades shouted a warning the knight had just enough time to rise and kill his opportunistic opponent. The chronicler records that the knight “managed to get to his feet, And left his duty incomplete.”

The Crusaders would not be goaded into a premature assault, and the Turks could make no impression on the outer protective screen of foot soldiers. The common soldiery may not have been able to afford expensive mail, but the various types of quilted or padded jerkins were surprisingly effective. At long range Muslim arrows could not penetrate such fabric, though a lucky shot might hit a face or an exposed body part. Some Crusaders wore amulets around their necks as added protection. In a separate incident, one unlucky soldier’s hauberk was pierced by a Saracen crossbow bolt, but was deflected by a small container the man wore as a kind of talisman against just such danger. The container bore a slip of parchment that was inscribed with God’s names.

The Crusaders would not be goaded into a premature assault, and the Turks could make no impression on the outer protective screen of foot soldiers. The common soldiery may not have been able to afford expensive mail, but the various types of quilted or padded jerkins were surprisingly effective. At long range Muslim arrows could not penetrate such fabric, though a lucky shot might hit a face or an exposed body part. Some Crusaders wore amulets around their necks as added protection. In a separate incident, one unlucky soldier’s hauberk was pierced by a Saracen crossbow bolt, but was deflected by a small container the man wore as a kind of talisman against just such danger. The container bore a slip of parchment that was inscribed with God’s names.

Generally, though, Turkish missiles were ineffective. Saladin’s secretary Baha al-Din, recalled, “Our arrows made no impression on them [the foot soldiers], men who had from one to ten shafts sticking in their backs, yet trudged on at their ordinary pace and did not fall out of their ranks.” The knights’ chain mail hauberks left them even better protected, so arrows tended to deflect, break on impact or stick into the metal links without penetrating. On one occasion a knight was hit by no less than 50 such missiles, yet fought on unscathed. Feudal lords, knights and common foot soldiers alike must have looked like human porcupines as the march progressed.

Muslim missiles might have been more effective at closer range, but the horse archers had to keep their distance because of Crusader crossbowmen. Baha al-Din ruefully admits that the Christians “struck down horse and man among the Muslims.” Showers of Saracen arrows, designed to be lethal and punishing, were neutralized by extreme range to a petty nuisance.

Saladin Makes His Move

Richard’s army reached Caesarea, where it was supplied by cargo ships from the Crusader fleet. Lionheart’s basic strategy was proving sound, even brilliant. Saladin’s troops had tried a scorched-earth policy, torching everything in the Crusaders’ path, but with the ships nearby the Franks did not need to live off the land. The fleet was the army’s umbilical cord, a literal lifeline that gave aid and nourishment to the struggling host.

Because Saladin was unable to trick Richard into a premature attack, the Sultan decided to risk a full-scale battle. The risk was indeed great, because Richard was the greatest military commander of his generation, not some spineless cipher like Guy of Lusignan. It was clear that something had to be done, because if Lionheart was not stopped soon he would reach Jaffa. The Sultan decided he would attack on a coastal plain about two miles wide just north of the town of Arsuf.

On September 5 there was a brief lull while peace negotiations were opened. Lionheart’s army was in the forest of Arsuf, coastal woods that carpeted the undulating hills like a green carpet. Many Crusaders were uneasy, reasoning correctly that this verdant patch could quickly become a death trap if the Saracens decided to start a fire. A forest can conceal as well as provide comfort and shade; somewhere lurking amid the foliage was Saladin’s army.

A parley was conducted between Richard and Saladin’s brother al-Adil, better known to the Crusaders as “Safadin.” Courtesies and comments were freely exchanged, because a Crusader named Humphrey of Toron was present to act as interpreter. The episode was a charade, a political smokescreen, because both sides were playing for time. Richard told Safadin if they wanted peace the Muslims had to “restore the whole land to us,” conditions that were plainly impossible. Safadin departed and the war continued.

Richard the Lionheart broke camp early in the morning of September 7, 1191. The Crusaders emerged from the forest of Arsuf and once again found themselves hugging the Mediterranean coast. When estimating the size of the Crusader army authorities differ wildly. Some say Richard had as few as 14,000, or as many as 50,000. Medieval armies tended to be small, so probably the real number was closer to the lower figure. In similar fashion Saladin’s Saracen host is said to have been between 30,000 and 60,000 men.

Whatever the numbers, most agree on Richard’s dispositions. The Knights Templar were in the van, followed by a battalion of knights from Brittany and Anjou. King Guy of Lusignan was next, leading, however ineffectually, a party of knights from his own home region of Poitou. The center was anchored by a four-wheeled, mule-drawn cart that carried Richard’s standard. Lionheart’s colorful banner flew from a wooden mast painted white with red spots and surmounted by a cross. The standard cart was protected by a mass of English and Norman knights. Richard himself stayed near the center, where he intended to direct the movements of his troops by means of trumpet blasts.

Next in order of battle were the French knights, most of whom disliked Richard but coveted the gold he paid them. Besides, Richard’s fame was a magnet, attracting them to his service almost in spite of themselves. The Knights Hospitaller formed the rear guard, a position of great responsibility that demanded cool heads as well as hot blood.

Richard loved fighting, but he let his head rule his heart, and refused—for the present—to be in the forefront of the line. The infantry was drawn up in battle array in an almost continuous line, once again a buffer and shield for the mounted knights that were just behind their lines. Another one of Lionheart’s innovations was a kind of “flying column” of picked knights under Hugh, Duke of Burgundy. This unit, which included in its ranks such stalwarts as James of Avesnes and William of Barres, roamed at will, able to plug any weak points in the Crusader line, yet also ready to enforce fragile discipline among the troops.

Like Legions of Satan Emerging From Hell

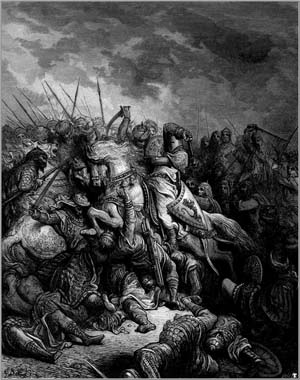

Without warning Saladin’s troops emerged from the forested slopes and swooped down onto the plain, thousands upon thousands of horsemen spilling over the hills like a human avalanche. The ground quaked with the impact of so many hoofs, and great thick coils of dust drifted skyward to mark their passage. Sunlight caught the tips of Muslim lance points, causing them to sparkle like a sea of diamonds, and just under the twinkling spears thousands of pennants and banners merged together to form a kind of silken “beast” that rippled in the bright morning sun. Onward they surged, bearded faces no doubt shouting their “Hai, Hai” battle cry to the accompaniment of booming drums and shrill trumpets.

It must have been a frightening spectacle to the Crusaders, seasoned warriors though many of them were. To the Crusaders their Muslim foes were like the legions of Satan emerging from Hell, yet by this time the Saracens had won a grudging admiration from their implacable foes. Third Crusader chronicler Ambroise was almost mesmerized by the display, particularly noting the Turk’s colorful scarlet turbans. To the poet the Turks moved “fearsomely, With their

red headdresses on high, Like ripely laden cherry trees.”

The Muslim flood smashed against the Crusader infantry lines, but the “dam” held and the tide ebbed. Crossbow bolts zipped through the air, impaling man and beast alike and felling scores of Muslim “cherry trees.” Turkish soldiers and their mounts tumbled to the ground, red headdresses merging with the bloodied sands. Momentarily repulsed, the Muslim survivors wheeled about, reformed, then charged again. It was a pattern that was to be repeated scores of times as the battle raged on.

Saladin’s heaviest attacks were directed toward the rear guard. Choked by dust, pelted by showers of arrows so thick it was said they dimmed the sun, the Hospitallers were at the end of their tether. Every instinct told them to charge and scatter their tormentors, but when the Grand Master of the Order William Borrel asked Richard’s permission to attack it was refused. Lionheart was no fool, and he knew that a knightly charge had to be precisely timed for peak effectiveness.

If a charge was launched too soon, the more mobile Muslim horsemen would scatter to the four winds. Worse still, a knightly charge would eventually wind down like a clock, its force dissipated for lack of contact with the enemy. Knights tended to be very individualistic in their quest for glory, and in pursuit their ranks tended to break up. Saracens had a nasty habit of retreating, then turning about and attacking with renewed vigor. Suddenly confronted with a resurgent enemy, the knights would be mounted on exhausted horses and very vulnerable to attack.

Lionheart in His Element

Richard’s army was a multinational, multilingual force rent with personal animosities, political jealousies, and conflicting loyalties. The English King was the glue that cemented this disparate force together, its effectiveness a tribute to his military skill, courage and personal charisma.

The Hospitallers were like a coiled spring, and as tensions rose it became harder and harder to obey Richard’s firm command to stay put. Goaded beyond all human endurance, the Marshal of the Hospitallers and a Norman knight named Baldwin Carew spurred their horses to the attack. The feckless pair squeezed through the infantry and galloped forward, the battle cry of “St. George!” on their lips. Soon the entire rear guard joined the attack, the foot soldiers parting ranks to let the black-mantled tide seep through. A kind of “domino” effect swept though the ranks, as French chivalry became infected by the offensive spirit and joined their Hospitaller comrades.

Richard could have held part of the army in check, but once launched, the King knew the charge had to be fully supported if it had a chance of success. Luckily the Hospitaller charge was only slightly premature, so Lionheart was happy to lend support. Drawing his great sword, the King of England led his English and Normans into the fray, joined by the remainder of the mounted army. The knights had their lances couched under their arms, impaling victims as soon as contact was made. If a lance was shattered or otherwise rendered useless, the knight switched to sword for close-in fighting.

Lionheart was in his element, giving and receiving blows with cheerful abandon. Fueled by adrenaline and prodigious strength, Richard’s sword arm did terrible execution. The King’s sword hacked off arms at a single swipe and bit deeply into torsos as if chain mail were woolen cloth. In a later battle it was said Richard’s blade chopped Muslim heads “in two from their helmets to their teeth; others lost heads, arms, and other limbs, lopped off at a single blow.” No doubt Lionheart performed similar deeds at Arsuf.

Saladin’s army began to disintegrate under the hammer-like blows of the rampaging knights. Yet there was a still a chance to turn the tables on the advancing Crusaders. Some Muslim units began to rally, and a force of some seven hundred Mamlukes gathered around the banner of Taqi-al-Din, Saladin’s nephew and one of his best generals. A few isolated knights were cut off and slaughtered, including James of Avesnes, one of the great examples of 12th century European chivalry. But Richard remained calm, appraised the situation, rallied the disordered knights and led them in two additional charges that swept away Muslim hopes.

Richard’s Legend Grows

The Muslim host wasn’t merely defeated; it was utterly routed. Saladin himself was unable to halt the fugitives, and had to accept the inevitable. It was a bitter pill to swallow, and as his secretary remembered, “God alone knows what intense grief fills his [Saladin’s] heart.” Perhaps even more devastating were the psychological wounds Richard had inflicted on the Muslims. Saladin, who bore the proud epithet of “Al Nasir” (the Victorious), ended the battle with his aura of invincibility shattered forever.

To the Muslims Richard the Lionheart became a superhuman foe, a man whose very name would strike fear in the bravest. Baha al-Din wrote, “All of our men were wounded, if not in their bodies, in their hearts.” The Battle of Arsuf had been a notable Crusader victory and a triumph for Richard personally. It was said seven thousand Muslims perished in the debacle, including 32 emirs. Normally penniless foot soldiers had a literal field day stripping and robbing Muslim corpses. Mamluke notables often carried gold and other wealth on their persons into battle.

Richard moved on to Jaffa, adhering to his original plan of securing the coast before moving inland. The battle was over, but not the Third Crusade, which dragged on until the fall of 1192. Just when Richard seemed on the very brink of capturing Jerusalem, political considerations or sheer lack of resources stayed his hand. The war ended in a five-year truce that some must have considered a stalemate. Richard departed for home, leaving behind a growing legend as England’s greatest warrior king.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments