By Jonathan North

At 11 o’clock on the evening of June 23, 1812, the first elements of Napoleon’s mighty army marched on three pontoon bridges over the river Niemen and set foot on Russian soil; the epic invasion of Russia had begun. For this massive undertaking Napoleon had assembled an enormous force, drawn from every corner of Europe. Some 450,000 men poured into Russia that summer.

Napoleon hoped for a quick campaign and decisive engagement, the type he was used to, and he gave three weeks’ rations to his men. The Russians did not oblige. They pulled back in an orderly fashion before the invading host, withdrawing deeper and deeper into the heart of the Russian Empire. The Russian commanders, Barclay and Bagration, more by necessity than design, marched eastward and, with a combination of skill and staggering good fortune, succeeded in avoiding the decisive battle Napoleon so ardently sought.

The speedy advance into Russia wrought a terrible toll on the masses of imperial troops; Napoleon’s soldiers found themselves tormented by the heat of a Russian summer and an almost complete breakdown in supplies. Few, save for the ever-active vanguard, fired shots in anger before the Grande Armée reached Smolensk seven weeks into the invasion. There, in a confused and desperate battle, the two sides fought the first major action of the campaign. It ended in a defeat for the Russians and, having suffered 6,000 casualties, they slipped out of Smolensk, abandoning the burned-out remnant of a once-impressive city, and again resumed their exodus eastward.

Russia’s Terrible Predicament

Smolensk had not been the decisive confrontation the French desired. After the fighting died down, a number of senior commanders sought to end the interminable advance by advocating that the army halt in Smolensk, gain some respite from the relentless marching, and prepare winter quarters. But Napoleon still sought the specter of the battle that would end the campaign. He pressed his subordinates to continue the advance and push on toward the new goal—Moscow. The Russians would either defend the city or its loss would bring them to their knees so that the Czar, surely, would sue for peace.

As they drew closer to the ancient city of the Czars, the Russians were faced with a terrible predicament: They could continue their retreat and abandon Moscow to the enemy or stand and fight the greatest captain of the age and his formidable army.

The Russians, narrowly avoiding disaster as they withdrew from Smolensk, considered making a stand, and after Smolensk, demands mounted for a new commander to replace the generals who had done nothing but backstep. The Czar succumbed to the pressure and turned to the crafty Kutuzov to lead the army. It was an inspired choice; Kutuzov, recently successful against the Turks, was very much a soldiers’ general and one, it seemed, capable of lifting the army’s—and nation’s—morale. Kutuzov joined the army on August 27, reviewing his demoralized troops as they marched through Gjatsk. On the 29th the French received news that Barclay had been superseded by Kutuzov, and Napoleon intuitively guessed that this was a sure sign the Russians would offer battle before Moscow. Keen to keep the initiative, he started gathering his forces, pulling in detachments, and hounding his jaded cavalry to press the Russian rear guard closely.

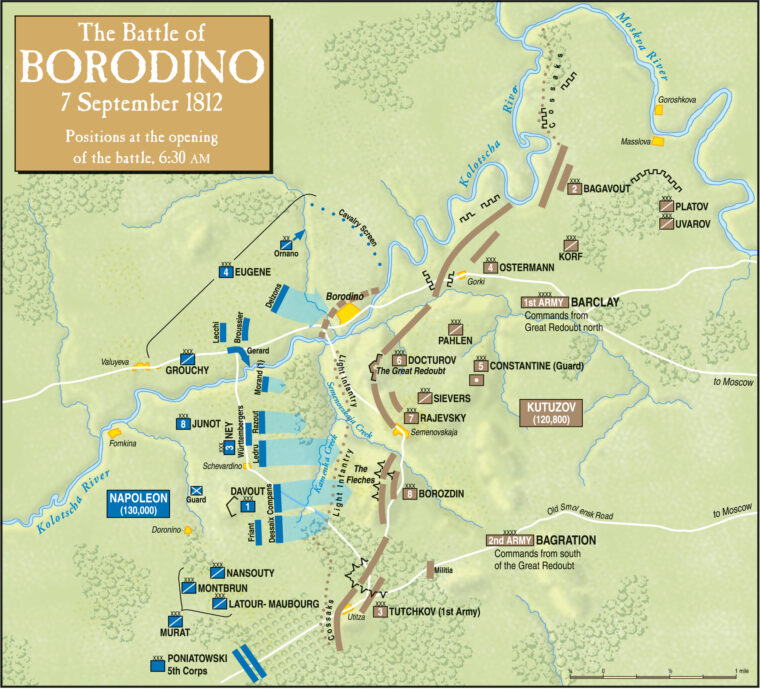

Skirmish followed skirmish as the bickering Davout and Murat jostled the Russian rear guard under Konovnitzin through the first days of September. Then, on the 5th, Murat’s cavalry stumbled across the Russian army drawn up and ready for battle around the little village of Borodino. Kutuzov had at first considered giving battle around Gjatsk but had then selected a strong position before the town of Mojaisk, 70 miles west of Moscow. The rolling countryside provided the Russians with a number of opportunities for a defensive battle, and they augmented the natural features of the terrain with some impressive earthworks and redoubts, constructed on September 4 and 5.

Borodino village—which effectively formed the right of the Russian position, although some troops were initially placed to the right of the village—was on the Kolotscha River, and on the opposite bank, to the left of the village rose a plateau that the Russians fortified and branded the Great Redoubt. To the left of this lay the partially dismantled village of Semenovskaja, and beyond that lay more earthworks (the fleches, or chevron-shaped defenses pointing toward the enemy but open on the rear). If the French launched a frontal assault, all these positions would be partially protected by meandering streams and gullies that lay between the two armies.

Kutuzov Crammed 120,000 Onto the Tiny Battlefield

The left of the Russian position was protected by extensive birch and pine forests. The village of Utitza, on the old Smolensk-Moscow road, in a clearing among the trees, formed the extreme limit of the Russian left flank. The last feature of note was the Schevardino Redoubt, one mile in front of the Russian position and intended, it seemed, to delay the French advance and win some precious time. Kutuzov, surrounded by his bickering staff, obtained a good view of the battlefield by setting up headquarters a mile behind Borodino and close to the village of Gorki.

Historians vary in their estimate of the troops available to the Russian general, but it seems that he crowded and crammed nearly 120,000 men onto the small battlefield. Importantly, 19,000 of these were Cossacks and hastily raised militia, although some of the latter were quickly incorporated into the line regiments to boost their ranks. Kutuzov had put considerable effort into ensuring that the infantry was well supported by artillery, and he could call upon 640 cannon. Barclay commanded the right wing and center of the Russian army, and the fiery Bagration took charge of the more exposed left.

Davout’s troops quickly went into action on the afternoon of the 5th, launching an assault on the Schevardino Redoubt. This was defended by General Neverovskii, who had shown considerable enterprise at Krasnoi during the Russian retreat, and his 27th Division. One of Davout’s divisional generals, General Compans, was directed to attack the Russian earthworks and he sent the 57th and 61st Line forward. The initial attack was met by a withering fire, but the French were supported by well-handled artillery that successfully wore down the Russian defense. The French stormed the Redoubt, the Russians fed more men into the fray, and the struggle rapidly intensified into a bitter battle for the possession of the hastily erected earthworks. When Poniatowski’s Polish troops were brought forward to support Davout, the Russians took advantage of the confusion of darkness and, toward midnight, fell back to their main battle line.

The next morning a delighted Napoleon rode forward to examine the Russian positions. The battle he had so eagerly sought was, at last, imminent. His troops, pressing forward along the new Smolensk-Moscow road, no doubt shared his enthusiasm, for they had spent months marching and now hoped to finish the campaign in one swoop. Napoleon could count on 132,000 men and 587 guns. The men had suffered countless trials and tribulations but were now certainly in high spirits. Unfortunately, the condition of the army’s horses left much to be desired and would impair the performance of the French cavalry and artillery.

Strangely, there was no fighting on the 6th. Napoleon discussed plans with his subordinates, rejecting Davout’s plan to outflank the Russian left wing, and issued orders for his troops to take up battle positions that night. The emperor, suffering from a bad cold, selected the remains of the Schevardino Redoubt for the location of Imperial Headquarters, pitched his tent, and prepared himself for the greatest battle of his career.

Tension and Excitement Precede the Battle

That evening the French prepared themselves for the forthcoming struggle. In the 18th century Marshal de Saxe had written that generals should “feed the soldiers before leading them against the enemy,” but Napoleon’s troops were tormented by lack of food—Lieutenant Vossler noted that his prebattle supper consisted of “a miserable plateful of bread soup oiled with the stump of a tallow candle.”

Many viewed the coming battle with foreboding; for others it was a welcome release. Most were confident of victory, as a German surgeon, Heinrich von Roos, noted: “We’d seen the Russian position and it was good, and we saw their entrenchments and, behind them, masses of troops, their weapons shining in the sun. We knew they had numerous artillery and that they would have made every effort to gather in as many troops as they could for the impending confrontation. The battle was sure to be tough, for both sides.

“We were convinced that our army was superior in number and that we were better acquainted with the practice of war. But we knew that the Russians were steady, and fought obstinately even against canister.”

The Russians, too, were in good spirits and were better supplied in terms of food. The army’s confidence was now greater than it had been during the rest of the campaign. General St. Priest thought that “our army is in good spirits and, thank God, in good condition.” Woldemar Löwenstern, Barclay’s aide-de-camp, agreed: “The army’s morale is excellent,” he wrote. “Soldiers, officers and generals all burn with the desire to fight or to die.”

There also had been little contact between the two armies on the 6th, but evidently the proximity of the enemy was too much for the curiosity of some of the soldiers. Ilya Rodojitsky, an artillery officer in the Russian 11th Division, recalled a close encounter on the evening of the 6th: “We forded a stream and passed the remains of a burnt village. Five hundred meters before us we saw a cordon of French dragoons and, behind them, some dismounted cavalry. We got closer to them, almost to within range, and could even make out the dragoons’ faces. They wore huge helmets and cloaks made of a light-colored material. They were like statues on their horses. After having had our fill of looking at the enemy we hurried back to our guns without, fortunately, having paid the price for our audacity.”

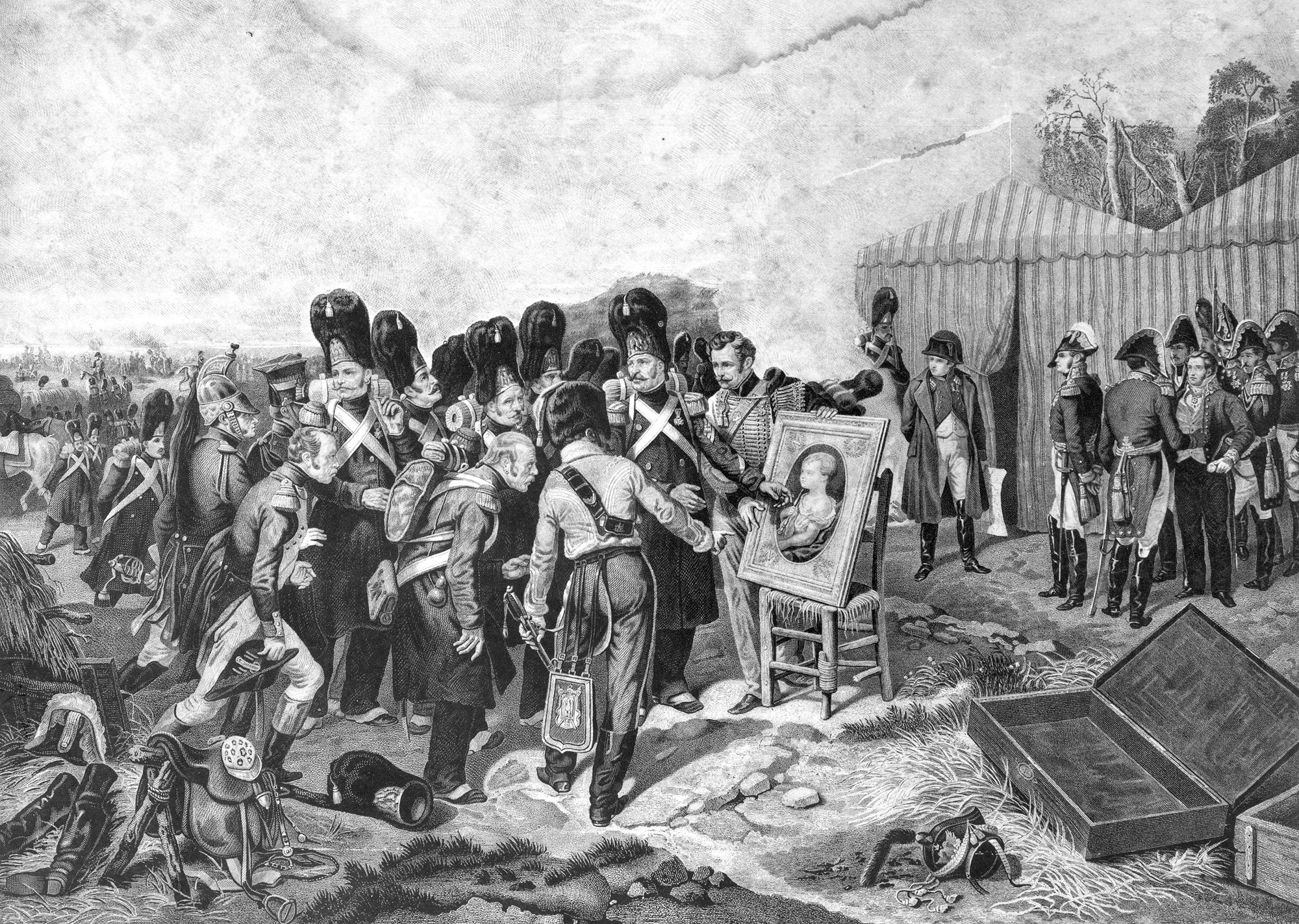

Night fell and 250,000 men settled down to sleep. Roman Soltyk, on Napoleon’s staff, remembered how the emperor began the day as the dawn of battle broke: “The night was cold and Napoleon was affected by a bad cold which practically robbed him of his voice. However, at three the next morning he mounted his horse and rode along the line to reassure himself that the enemy still intended to give battle and that they had not altered their position. When I next saw him he was on the grass by the redoubt. His staff was some 30 paces behind him. By his side was Berthier, Caulaincourt and Duroc; his marshals, to whom he had just given his orders, had left.”

His marshals had been directed to launch a series of frontal assaults against the enemy positions. Eugene, minus a division of Italians left near Gjatsk but supported by two of Davout’s divisions, was to attack the Russians around Borodino and seize the Great Redoubt; Ney and Junot were opposite Semenovskaja village; Davout was to attack the fleches; and Poniatowski was directed to attack Utitza and its knoll on the extreme right of the French. The cavalry were supposed to act in support of these infantry assaults and the Imperial Guard were kept in reserve.

Dawn of the 7th broke and the battle began. Eugene’s infantry were the first to advance; Delzons’ division attacked Borodino, held by a regiment of Russian Guard Jägers, and the French poured into the village. The Jägers fell back over the Kolotscha.

“In the Space of Just Ten Minutes, We Had Lost the Majority of Our Men and Thirty Officers.”

A Russian officer recalled: “The retreat was difficult, and the crossing of the bridge dangerous. I have never been exposed to such a deadly fire. The crush on the bridge was so strong that I was almost pushed into the river. Our men suffered heavily and quite out of proportion to the amount of time we had actually been in battle; in the space of just ten minutes we had lost the majority of our men and thirty officers.”

The French pursued, General Plauzonne and the 106th Regiment pushing over the river, but they were cut down by Barclay’s troops and the Russians were able to demolish the bridge. Eugene then turned his attention to the Great Redoubt, but a far fiercer struggle was taking place farther south as Marshals Davout and Ney sought to seize the fleches, punch a hole in the Russian left, and swing behind the Russian center. Had this audacious plan worked, the bulk of the Russian army would have been destroyed. Thanks to Bagration, who commanded the Russian left flank, and the superb conduct of the troops of the 2nd Combined Grenadier Division and Neverovskii’s 27th Division, the scheme failed.

The French artillery first opened up at 6 o’clock but found itself placed out of range. It was manhandled forward and began to pulverize the Russian position with the fire of more than a hundred guns. An officer in Neverovskii’s division, Andreev of the 50th Jäger Regiment, remembered this opening barrage with awe: “During the night we could hear singing, drum rolls and music played by military bands coming from the enemy camp. At dawn we saw that a powerful battery had been established opposite us. Then something amazing happened; the noise from the enemy cannon, as they opened up, was so loud it drowned out the sound of all other firing. This bombardment lasted until noon and clouds of smoke obscured the sky.”

The fight for the fleches was extremely bloody, and few episodes of the Napoleonic Wars would equal the slaughter as these hastily constructed earthworks were fought over, then taken, and lost again and again. Compans’ troops were the first to advance, dense columns snaking over the plain before the Russian position. Compans’ 57th Line took the southern fleche around 7 o’clock, but the regiment was thrown back by a well-directed counterattack. Compans and Davout were wounded and the French were compelled to fall back. Russian cavalry pursued but were fired upon by French reserves.

Recalled one participant: “We saw Russian cuirassiers charge and fall upon our troops like a tempest. The charge wasn’t directed against us but against a battery of 30 of our guns. The cavalry passed close by and we fired into it; it didn’t slow them down, and neither did the storm of canister coming from the guns themselves, and they fell upon the artillery, cutting down those gunners who weren’t fast enough to throw themselves under their cannon. Soon, however, the Russians were thrown back in disorder by fresh French cavalry and again had to pass us by. Our troops fired into them and even ran forwards with their bayonets, hoping to cut off their retreat.”

Russian Counterattack

Marshal Ney now supported Davout, sending Ledru’s division to help. The French again stormed forward, General Desaix being wounded, and, climbing a mountain of dead and wounded, pushed into the earthworks. The Russian artillery stuck to their guns—having been ordered to “stand their ground until the enemy are within the closest possible range; a battery captured will have inflicted casualties on the enemy that will more than compensate for the loss of a gun”—but Russian cavalry and infantry quickly counterattacked.

Captain Bonnet in Ney’s corps described the agony of the attack on the fleches:

“Our division moved forward to attack the three redoubts to its front. Moving slightly to the right, and sweeping through some undergrowth, we pushed toward the first redoubt and came under artillery fire. The first redoubt was taken by troops in front of us and we therefore marched on the second position. Our four battalions were deployed one behind the other. The redoubt, and four cannon, fell to our men. Before long a swarm of enemy skirmishers advanced towards us from the left while a heavy column of infantry came at us. I deployed my battalion and attacked the column; it fell back but exposed us to canister from artillery positioned in a village. The battalion was almost swept away, men falling by the dozen.

“We pushed on toward a ravine that separated us from the village but caught sight of another enemy column advancing steadily toward us. Those of us left turned tail and retreated, maintaining, however, a steady fire against the column. We reached the redoubt but could not defend it, as it was open on their side. The Russians darted forward and we evacuated the position. I jumped off the earthworks and ran, narrowly escaping a Russian who grabbed at my greatcoat. I jumped over the ditch. I was shot at at least twenty times but escaped unharmed, although my shako was hit.”

Such was the murderous nature of the fighting that Ney was obliged to send in another division, this time the 25th Division composed of Württembergers, in support. Junot’s Corps assisted and Murat, too, lent a hand, calling up Nansouty’s cavalry to counter the threat posed by Russian cuirassiers. The Russian attack failed and now the French launched a counterattack, the 57th Line again advancing and eliciting from Bagration cries of “Bravo! Bravo!” as they marched steadily and in almost perfect order through the carnage.

Just then Bagration was struck in the leg by a fragment of canister and had to be carried off the field. His troops lost heart and the French succeeded in establishing themselves in the fleches. The Russians fell back over the Semenovskaja stream, maintaining their fire, but by now seriously depleted.

“An Enemy Battery of Twenty Guns was Constantly Bombarding Them”

As Andreev noted, “I came across Bourmin, our commander, at the head of 40 men. That was all that remained of our regiment.” The French were too exhausted after six hours of fighting to rejoice in their first success; the battle was not won and the troops in the fleches, which were open on the Russian side and offered no protection, still found themselves facing obstinate Russians, now commanded by Docturov, and devastating artillery.

An officer in Ney’s III Corps wrote that “our troops were stationed in one of the Russian redoubts; an earthwork which the enemy had defended most stubbornly, then lost, then retaken, then abandoned one last time. Our men had played a key role in the struggle and were now resting on their laurels. But it was no bed of roses. An enemy battery of 20 guns was constantly bombarding them.”

As the struggle for the fleches was taking place, Poniatowski had attempted to take Utitza from Tutchkov. His depleted corps found the task assigned to them too ambitious and Napoleon’s Poles, after some initial success, spent most of the day in a fruitless battle of attrition in the woods.

After Borodino village had fallen, the French concentrated on their next objective: seizing the Great Redoubt. While Ney and Davout were embroiled in the attack on Bagration, Eugene, supported by some of Davout’s troops, threw his men against this formidable Russian position.

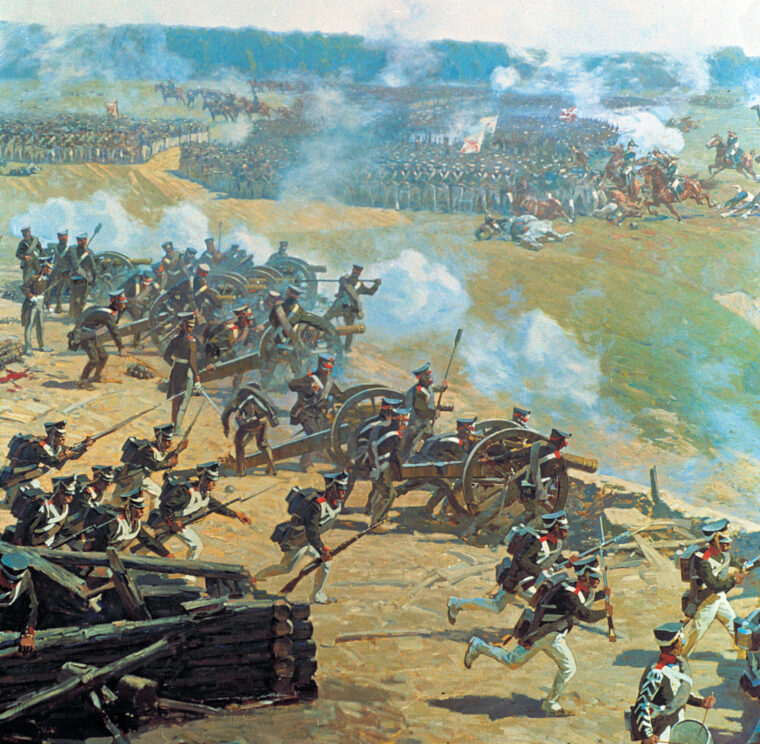

The Great Redoubt had been constructed with care and attention by Russian sappers. General Rajevsky, a stubborn and capable officer, was placed in command of the position and oversaw the construction of the defenses. Rajevsky wrote, “We built these batteries ourselves. A sapper officer advised us to dig a series of wolf-pits 150 meters before the redoubt as the position was at risk of being overrun by cavalry. We did this and now all we have to do is await the enemy.”

The enemy was not long in coming. At 10:30, supported by a powerful artillery barrage and a cacophony of drums and martial music, the French, in full dress, moved to the attack. They drove in Russian skirmishers, placed in the ravine before the redoubt, and pressed steadily up the slope.

The Decisive Moment

Rajevsky wrote: “This was the decisive moment. As soon as the enemy came into range, the artillery opened up and the enemy columns were obscured by smoke A second volley rang out and one of my staff officers shouted to me ‘General, save yourself!’ I turned around and caught sight of some French grenadiers who had penetrated the redoubt. It was with some difficulty that I reached my left wing.”

François, of the 30th Line, took part in the attack and described his experiences:

“Our regiment received the order to advance. We reached the foot of the slope, within range of the Russian artillery, and we were almost swept away by a storm of canister from the battery in front of us. We had to keep jumping up to allow roundshot to roll harmlessly through our ranks. However, entire files and platoons were obliterated and gaps began to appear in our ranks.

“General Bonamy, at the head of the regiment, dressed the ranks and led us forward at the charge. We stormed up the slope and clambered over the earthworks; I jumped into the redoubt just as a Russian gun had been discharged. The Russian gunners met us with handspikes and ramrods. We fought hand-to-hand and they were redoubtable adversaries. I defended myself with my sword and killed more than one gunner. I’ve been in many campaigns but I’ve never been in such bloody fighting and against soldiers as tenacious as the Russians.”

Nevertheless, the Russian infantry broke and fled from its position, but Rajevsky, supported by General Yermolov and the gallant 22-year-old General Kutaisov, was quick to counterattack: “The enemy, attacked from both flanks, was pushed back and the commander of the enemy column, General Bonamy, was taken prisoner, covered in wounds. On our side, Kutaisov was killed and Yermolov was wounded. I returned to the redoubt. My corps was so depleted that it counted 700 men at the end of the battle and 1,500 the next day.” (Stragglers and lightly wounded men returned to the ranks the following day; hence, the increase in numbers.)

Bonamy was wounded 15 times, captured by Grenadier Zolotov of the 18th Jägers, and taken to the rear. His troops fell back in confusion, the 30th Line having been destroyed. The attack had failed but the French regrouped and prepared a new assault. Their attention was deflected by a massive cavalry charge, 5,000 men led by General Uvarov, above Borodino and around the left flank of the French. Although crowned with some initial success—the Russians scattered Ornano’s cavalry—Uvarov was beaten off by Delzons. The Russian cavalry, many of whom were Cossacks, fell back. Despite such an ignominious ending, Uvarov’s action had shaken the French left wing and stood testament to the fact that the Russians still had plenty of fight.

“I Found Ostermann Exposed to the Most Deadly Fire I had Ever Seen”

Nevertheless, pressure on the Great Redoubt was growing as the French right flank, having taken the fleches, was now exerting itself against Semenovskaja village. Friant’s troops seized the ruined village and punched a hole in the Russian line. The French called for support, Murat sending General Belliard to plead with the emperor, begging him to send in the Imperial Guard—mere spectators to the battle throughout the morning—and deliver the coup de grâce. Napoleon refused, having been shaken by Uvarov’s charge and conscious of the fact that he was too deep into Russia to risk all his army. His concession was to send forward the Guard artillery and three regiments of Poles belonging to the Young Guard.

Thus the artillery was rushed toward Semenovskaja, adding its fire to the French artillery already wreaking havoc on the masses of Russians trying desperately to close the gap in their line. Whole lines of Russians were swept away, their green-jacketed corpses littering the slopes behind the village. Löwenstern came across Ostermann’s troops on the receiving end of the French artillery: “I found Ostermann exposed to the most deadly fire I had ever seen. His corps had been smashed. As I was speaking to the general, roundshot fell about us in such quantity that horses were knocked over, men killed and we were showered with earth at every moment. Prince Galitzyn was badly wounded; General Bakmetiev lost his leg and Ostermann himself was wounded.”

But the Russian artillery was also active. Because the infantry divisions were seriously depleted, the French had been obliged to use cavalry to flesh out their lines and to counter the threat of the ever-active Russian cavalry. It was a costly decision to make—the cavalrymen were perfect targets for the Russian gunners as line after line of mounted men stood motionless in the sun hour after hour. An infantry officer observed “long lines of French cavalry in whose ranks the enemy artillery blasted bloody lanes at every moment.”

A cuirassier captain described the unnerving experience firsthand: “The regiment was not required to charge but spent the day under fire from roundshot, shell and canister. We were surrounded by the dead and the dying. On two occasions I went to inspect the faces of the cuirassiers in my company and see which of them were brave. I was proud of them and told them so there and then. Upon going over to see a young officer, Monsieur de Gramont, who was behaving well, I saw some terrible things. He was telling me that he had nothing to complain about, but that he would appreciate a glass of water, when, no sooner had we finished talking, a roundshot came over and cut him in two.”

General Montbrun, commander of the II Cavalry Corps, was mortally wounded at this time and the French lost hundreds of troops and precious horses. But the French and allied cavalry were now put into motion—they were directed to support an attack on the Great Redoubt. General Caulaincourt, at the head of the 5th Cuirassiers, charged and attempted to storm into the rear of the redoubt. Caulaincourt fell, mortally wounded, and the cuirassiers were beaten off.

General Lorge was next to attempt the bloody mission; his German and Polish heavy cavalry spurred their mounts forward before being raked by musketry and artillery fire. The cavalry pushed into the redoubt just as Eugene’s infantry clambered up the slope in front of the Russian position and hurled themselves over the earthworks.

A Terrifying Yet Majestic Battle

A Russian onlooker described the scene: “In the afternoon, as Prince Eugene’s troops launched themselves into their final attack against our redoubt, the cannon fire and musketry was such that it resembled a volcano. Swords, bayonets, helmets and cuirasses all gleamed in the fading sunlight. It was a terrifying yet majestic sight.

“We were positioned close to Gorki village and were witness to the entire bloody scene; our cavalry were locked in combat with the enemy’s and they shot, slashed and lunged at each other from all sides. The French came right up against our earthworks and, after a final discharge, our guns fell silent. A cry went up and we knew that the enemy had got into the position and that both sides would get busy with their bayonets.”

A Polish officer in Napoleon’s Young Guard, Heinrich von Brandt, also remembered the moment when the Great Redoubt fell: “A terrible roar, coming from the mouths of thousands of men, drowned out the noise of the artillery that was now raking our columns. When the smoke cleared, we saw that the Great Redoubt had been taken and that the French cavalry were issuing from it to charge the retreating, but still uncowed, Russians.”

Eugene had triumphed and the key to the Russian position had fallen to Napoleon. The French urged their cavalry forward, launching a series of charges designed to crush the Russians as they fell back. It was a decisive moment. Had the Russians broken, the battle would have turned into a rout. But despite their ordeal, they maintained a steady retreat, taking up new positions before the French could seize the initiative. The Russians held the French cavalry at bay, though Barclay was almost taken prisoner.

Löwenstern, Barclay’s aide-de-camp, wrote: “The general had his horse wounded by a pistol shot; it bolted and galloped off. Some French lancers pursued him and he had difficulty in escaping. His staff were dispersed but fortunately Colonel Zakreffsky, Kachinzov, Sievers and myself managed to reach him just as the lancers were about to lunge at him with their weapons. Our situation was improved by the arrival of the Izoum Hussars.”

A Scene of Confusion and Utter Chaos

Confused fighting followed. A German officer in the Russian army recalled: “The Izoum Hussars arrived on top of the hill and found themselves face to face with the French cavalry. The first squadron deployed and charged the enemy, winning time for the other squadrons to deploy. The French were halted by this ferocious attack and slowly fell back.

“It was a scene of utter chaos. French and Russian cavalrymen were intermingled, regiments were all mixed up as each cavalryman attempted to sabre his opponent. The cavalry were surrounded by the remains of our infantry divisions, hastily attempting to reform. If another French cavalry brigade had arrived then, in good order, they could have swept away our confused troops and blasted a hole in our center—for we had nothing to oppose them.”

A Saxon officer, fighting for the French, also left an account of the seesaw battle between the cavalry: “The Russians opened up on us at 1,100 paces with canister. Our guns replied and thick billowing smoke obscured everything, only the flashes from the gun barrels could be seen. It was as though hell had opened its doors to us. The effect of the smoke was exacerbated by clouds of whirling dust.

“Suddenly the enemy’s guns fell silent; the smoke and dust subsided. I saw numerous regiments of cavalry throw themselves against the batteries in the redoubt and oblige the Russians to fall back. Then we ourselves were attacked by a regiment of Russian dragoons and had to fall back to the far side of a ravine. The dragoons disappeared all of a sudden and we were now witness to a mass of Russian cavalry advancing against us. Shells exploded above us and roundshot showered us with soil and dust. We were there for a quarter of an hour at least and our ranks were considerably thinned. We begged our men to hold on just a little longer until some support came up.

“Suddenly the plain was covered with French cavalry; the closest to us were the grenadiers and cuirassiers. We were ordered to stay where we were and to support the French as they flung themselves against the enemy. We heard the enemy’s canister striking the cavalry’s cuirasses and helmets. They soon came up against the Russian cavalry and crossed swords; the enemy were forced to fall back but, in the meantime, his infantry had taken up strong positions from which it proved difficult to dislodge them.”

The battle was descending into chaos; groups of soldiers fought hand to hand; command passed to regimental and even to company levels. Vision was obscured by billowing clouds of smoke intermingled with dust; the roar of cannon and the screaming and shouting of thousands of men obliterated every other noise. Infantry, cavalry, and artillery, or a combination of all three, had failed to rout the Russians, yet Napoleon still refused to commit his reserve. The Russians had fallen back a thousand paces but had taken up fresh positions close by the village of Gorki.

“The Soldiers Received the Order to Lie Down While the Officers ‘Awaited Death Standing’ “

Their artillery continued to fire upon the French, as Heinrich von Brandt, part of the Young Guard now stationed in the ruins of the Great Redoubt, noted: “It was then that the terrible artillery duel, of which all historians speak, began. The redoubt, which to some extent sheltered us, was torn up by shot and shell. Shots soon began to fall amongst our ranks and our losses began to mount. The soldiers received the order to lie down while the officers ‘awaited death standing,’ as Rachowitz put it.

“He had just finished speaking when we were both splashed by the blood and brains of a sergeant who had had his head blown off by a cannon-ball just as he had stood up to go and talk to a friend. The horrible stains on my uniform proved impossible to remove and I had them in my sight for the remainder of the campaign as a memento mori.”

Both sides were exhausted, and toward evening, the fighting subsided all along the line. Kutuzov sent word of victory to the Czar but, after receiving detailed reports on the condition of his army, began preparations for a retreat that night. Napoleon’s shaken troops were amazed by the tenacity of their opponents and the order of their subsequent retreat. As Napoleon said to General Desvaux de Saint-Maurice of the Guard horse artillery, Borodino was “truly a battle of giants.” That evening, Roman Soltyk, attached to Imperial Headquarters, overheard a conversation between Marshal Ney and Murat:

“[Murat]—‘That was hard work. I’ve never been in a battle like it, especially for artillery fire. At Eylau both sides fired plenty of roundshot but here we were so close that it was almost always canister.’

[Ney]—‘We haven’t finished yet; the enemy must have lost tremendously and we must have shaken his morale; we have to pursue and profit from our victory.’

[Murat]—‘But they’ve withdrawn in good order.’

[Ney]—‘Good God, how can that be after such a slaughter?’”

Kutuzov had deemed a retreat necessary and first directed that his wounded be evacuated to Mojaisk and then that the army’s artillery and baggage should follow. Meanwhile the bulk of his army settled down to a miserable night. The French, too, had a nightmarish time, collapsing exhausted on the battlefield, surrounded by the corpses and groaning men.

Heinrich von Brandt paints a chilling picture of the scene: “We camped where we stood, surrounded by the dead and dying. We were completely without water and firewood but we did find oats, brandy and some other provisions in some of the dead Russians’ knapsacks. With some musket butts and splinters from a broken limber we managed to get a fire going and grill our house specialty—horse steaks. In order to make some soup we had to go down and get some water from the Kolotscha, one of the most terrifying experiences of my life.

43,000 dead, Wounded, or Missing

“In the shadows around each of the flickering fires, the agonized and tormented wounded began to gather until they far outnumbered us. They could be seen everywhere like ghostly shadows moving in the half-light, creeping towards the glow of the fire. Some, horrifically mutilated, used the last of their strength to do so. They would suddenly collapse and die, with their imploring eyes fixed on the flames.”

That dreadful night effectively put an end to the fighting—although there were a small number of Cossack raids in the early hours—and both sides could assess the cost of the 12-hour battle. The Russians suffered the most casualties—43,000 men were reported dead, wounded, or missing, although some of the missing rejoined later and 20,000 of the wounded recovered within seven months.

Thus Kutuzov had lost a third of his effectives in a single day. Twenty-three generals had been killed and wounded, and the most serious loss of all was Prince Bagration who succumbed to wounds seven days after the battle. Some Russian regiments were totally wrecked—the 6th Jäger had lost 920 men killed and wounded, the Shirvansk Line counted just three officers and 96 men left out of 1,300—and very few of the casualties had been taken prisoner.

Napoleon’s losses are harder to estimate. Evidence suggests that some 40,000 French and allied soldiers were killed or wounded and 49 generals were hit. Many of the regiments at the forefront of the action were completely shattered. Fouquet, of the 30th Line, wrote that his unit “had suffered greatly and that our five battalions had been reduced to two after the battle. Our general of division [Count Morand], general of brigade, colonel and major had been wounded; three majors and 16 officers killed and 52 wounded; and I hardly dare mention the loss amongst the soldiers.”

Officer casualties meant that for many junior officers the battle presented an unexpected and welcome bonus: promotion. Lehucher of the 57th Line wrote, in a letter home, of his own good fortune: “The battle cost us a good number of men, many of whom were my friends and I really regret their loss. I was fortunate enough to emerge unscathed even though my trousers and greatcoat were torn by a number of musket balls. The emperor is in the process of replacing those officers killed and has been gracious enough to accept my colonel’s suggestion that I be made adjutant. So I’m going to get rid of my knapsack and I’ll be wearing epaulettes from now on.”

Many Later Regretted That They Had Not Been Killed at Borodino

During the battle, Brandt had also commented on the possibilities the aftermath of a Napoleonic battle presented to those junior officers fortunate enough to survive: “A foot artillery battery close by us had lost every one of its senior officers and was now under the command of a very young-looking junior officer. He seemed to be adapting very well to his new role in the midst of this all too dreadful and horrific carnage which heralded rapid promotion for hundreds of such men.”

If the survivors were fortunate—although many later regretted that they had not been killed at Borodino, especially during the horrors of the winter retreat—the direst fate certainly befell the wounded. Most of these unfortunates died from neglect, having been deposited in the villages around Borodino.

Fantin des Odoards of the Imperial Guard outlines the fate of those unable to follow their respective armies: “Despite the speed of their retreat, the Russians had managed to bury their dead and those of their wounded who had died alongside the road. It is sobering to reflect that these people, whom we looked down upon as less civilized, show far more concern for their wounded, and respect for their dead, than we proud Frenchmen.

“We leave our wounded to die from want and only bury those corpses that get in our way. As for our neglect of enemy wounded fallen into our hands, it is beyond comprehension. Countless of these unfortunates expired on ground soaked with their blood; their pleas and supplications leaving our troops, heartless passers-by, unmoved. Those who survived now showed stoicism; unable to move or crawl away, they wrapped themselves in their greatcoats and awaited their fate with resignation.”

Harsh Winter and a Hollow Victory for Napoleon

Leaving Junot’s Westphalians the unenviable task of clearing the field—a task not fully completed—Napoleon continued the advance eastward. On the 14th, the French army stood before Moscow, city of the Czars, and looked down in awe on the shimmering domes and roofs of the imperial city. Kutuzov had resolved to save his army and had pulled back to the southeast, allowing the French to enter Moscow while preserving his troops for another day.

A week later most of Moscow had been burned and was reduced to ash. Confused, unable to bring the Czar to the negotiating table, and fearful of quartering his army in a ruined city, Napoleon called for a general retreat. Prevented by the Russians from following a more southerly route, the Grande Armée took to the line by which it had come a month after reaching Moscow. The winter set in early and was unusually harsh. Disaster for Napoleon’s army was the result.

Borodino was not the decisive victory Napoleon had so ardently desired. Although it allowed the emperor to enter Moscow and to claim that the battle had been a triumph, the long-term results of the battle showed how empty his claim was. Borodino, and the loss of Moscow, were insufficient to subdue the Russians. They continued the fight. Ultimately it was a fight they would win; 18 months later they marched into Paris.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments