By Michael D. Greaney

Arminius, war leader of the Cherusci, a powerful German tribe on the east bank of the Rhine, was livid. Germanicus Cæsar, the nephew and adopted son of Tiberius Claudius Cæsar, the new emperor of Rome, had just carried out a devastating and insulting raid deep into Cheruscan territory. The object of the raid was to rescue Segestes, Arminius’s sworn enemy, who was under house arrest and in danger of being executed for his efforts to broker a peaceful resolution to the ongoing conflict between the Cherusci and the Romans. Not only had Germanicus rescued Segestes and a large number of his family, he had also carried off Segestes’ daughter, Arminius’s pregnant wife, who had probably not wished to be rescued in the first place. The only one without any qualms was Segestes himself.

Immensely pleased to have carried out such an audacious raid under the very nose of a formidable enemy, Germanicus was the soul of diplomacy. He promised Segestes that his children and relatives would be kept safe and not enslaved as rebels, and that Segestes himself would be given refuge in Gaul. Germanicus then retreated across the Rhine and, once again displaying his innate tact and diplomatic skills, gave full credit for planning the raid to Tiberius, who knew nothing about it. At a stroke, Germanicus had managed to pull off an amazing feat of arms through sheer audacious nerve.

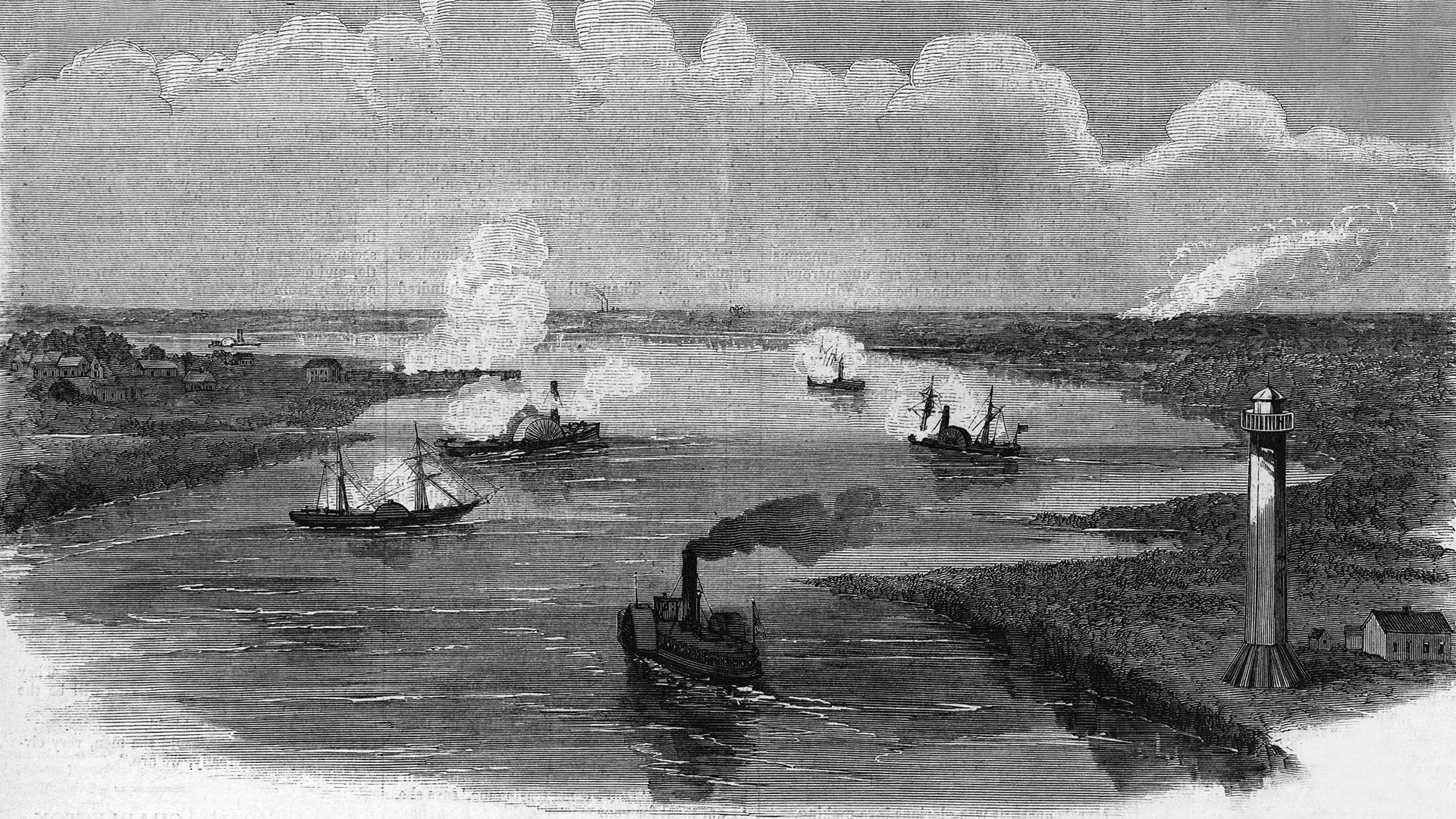

Memories of Teutoburgerwald

Arminius, the victor over the Romans at Teutoburgerwald six years earlier, wasted no time in organizing a counterstrike. He rallied the Cherusci, as well as a number of the surrounding tribes, to his side. A particular coup on Arminius’s part was to secure the allegiance of his paternal uncle, Inguiomerus, a long-respected ally of the Romans. Anticipating just such a pursuit by his rivals, Germanicus needed to take quick action to create a diversion and blunt the force of the anticipated Cherusci attack. He sent Aulus Cæcina Severus, a veteran of long service in Pannonia and Dalmatia, with his four legions through the territory of the Bructeri to the Ems River east of the Rhine. Cavalry cohorts under Pedo Albinovanus were detached and sent across the border into Frisia, bordering the North Sea. Germanicus then took his remaining four legions in a hastily constructed fleet across a lake that was drained by the Ems. The cohorts, cavalry, and marine contingent reunited at the river, where they were joined by a force from the Chauci, a local tribe that was loyal to Rome.

Next, Germanicus sent a small number of cohorts under Lucius Stertinius to checkmate the Bructeri, who had begun burning their personal effects preparatory to making an all-out assault. This military potlatch was a long-standing custom among the German tribes, symbolizing to the gods that the warriors had nothing to lose. During the ensuing battle, Stertinius’s men recovered the lost eagle standard of the 19th Legion, one of the legions massacred at Teutoburgerwald alongside their ill-starred commander, Publius Quintilius Varus, in 9 ad. Stertinius’s contingent rejoined the rest of the army, which then burned and pillaged its way through the country between the Ems and the Lippe Rivers until it drew near the killing ground at Teutoburgerwald. There, Germanicus diverted the troops to bury what remained of their luckless comrades and to pay their final respects. Most of the men had friends and relatives among the slain.

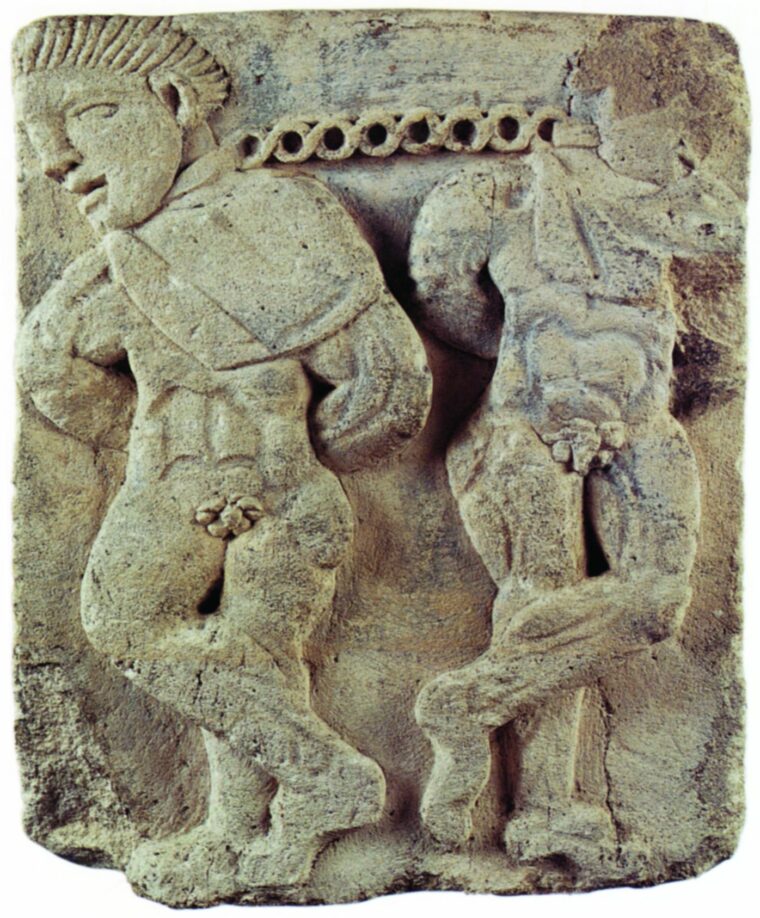

They easily located Varus’s camp, as well as a shattered breastwork and shallow entrenchment where a remnant of the original force had made its last stand. The ground was strewn with heaps of whitened bones of men and horses. Interspersed among the litter of military equipment were trees bearing human skulls nailed to the trunks, gory tokens of sacrifice to the German gods. Nearby groves, sacred places for the northern tribes, contained grisly altars where senior officers had been sacrificed. There were also pits in which Roman prisoners had been tortured and gibbets from which they had been hanged.

A mass grave was constructed, with Germanicus laying the first sod on the funeral mound. By paying tribute to the fallen at Teutoburgerwald, he hoped to turn a military expedition to avenge Rome into a political campaign for the conquest of Germania. This was contrary to Tiberius’s express orders. The policy under Augustus and Julius Caesar before him had been to extend the reach of Rome more or less peaceably wherever possible, relying on the innate desire of the barbarians to enter the empire and eventually become Romans themselves. It was not a policy that could be carried out by force of arms, as Germanicus rather optimistically believed.

Whatever the motive for Germanicus’s funereal ceremony, the effect on the troops was dramatic. To a man they were filled with a seething anger that matched the sorrow and horror they felt at the scene of a crime committed against their friends and relatives—indeed, the entire Republic. Having prepared his men emotionally to meet the enemy, Germanicus ordered a swift pursuit of Arminius and his followers. Catching up with them a short time later, the Romans believed that Arminius had made a grave tactical mistake, leaving the safety of the deep woods and making camp on open ground. Germanicus sent his cavalry ahead to rush the camp and sweep them back toward the main Roman force, catching the enemy in a classic pincer movement that was straight out of Frontinus’s Strategemata, a well-known Roman textbook on battle tactics.

Germanicus Withdraws

Unfortunately for the Romans, Arminius’s apparently foolish mistake in making camp on open ground was a trap. Arminius immediately turned his men around to face the Roman cavalry and, at the same time, gave the signal for a force previously concealed in the woods to charge the Roman flank. The cavalry was thrown into confusion by the unexpected assault by presumably unsophisticated barbarians. In fact, many of the Cherusci had themselves served as auxiliaries in the legions and were fully the equal of any Roman, as Varus had discovered to his mortal cost. The horsemen began to fall back.

The reserve cohorts immediately went in to stiffen the line, but were disorganized by the retreat of their comrades. The Germans began to force the Romans into marshy ground, a sure death trap for the cavalry. The situation began to take on the appearance of another Teutoburgerwald. At that moment, however, almost as if he were following a script, Germanicus brought up the regular legions in battle formation, a frightening panorama of the virtually unstoppable Roman war machine. At the sight of the dreaded eagle standards, the Germans retreated again, this time in earnest, leaving the Romans in possession of the field, but with nothing to show for their trouble—Arminius had escaped with his entire force intact. Germanicus’s luck had stuck by him, but it was beginning to look like it might be wearing a little thin.

Germanicus began his own retreat to the Ems River. The legions that had come by way of the river re-embarked on their ships, and some of the auxiliary cavalry were given orders to return to the Rhine by way of the Frisian seacoast. Cæcina’s four legions were once again put back under his direct command, and he was told to return to the Rhine via the “Long Bridges,” an extended causeway built a number of years previously by Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus through a vast swamp. The order caused Cæcina no little concern, as he worried that effecting repairs and protecting the workers would be impossible with his reduced force. To make matters worse, the causeway was now in terrible shape.

Cæcina’s March Through the Marsh

Cæcina’s route of march was everything that made Germania a nightmare for troops raised in wide-open Gaul or on the sunny Mediterranean. The ground was treacherous at best, all slimy bogs and sticky mud, with the occasional rushing stream to drown the unwary. The immediate landscape around the causeway was composed of rolling hills and woods. Arminius already occupied the high ground. Germanicus apparently had assumed that the Cherusci chieftain had run off and gone into hiding. On the contrary, Arminius, by dint of forced marches and knowledge of the territory, had managed to overtake the heavily laden Roman column. Cæcina hesitated briefly to assess the situation, then fortified a position at the beginning of the causeway from which the repair work could be carried out and the workers defended.

Arminius immediately ordered an attack. For a change, the swamp was as impassable for the Germans as it was for the Romans. Undeterred, Arminius’s men kept up tremendous pressure on the front and the flanks of the Roman position, trying to break through and attack the workers. Having received their orders, the workers resolutely continued making their repairs. Between the sounds of the battle and the din of construction, the clamor was tremendous. This only encouraged the Germans, who were accustomed to using noise as an extra weapon in battle.

Once again the situation seemed like a replay of the disaster of six years earlier. The Roman soldiers were bogged down by heavy armor in soft footing and could not maneuver well in the soaked ground. Standing in waist-deep water, it was impossible even to take the proper stance for throwing javelins. This had no effect on the Germans, who did not generally throw their spears but used them as unhilted swords, thrusting them at the enemy rather than using them as missiles. And while the swampy ground made fighting difficult for the Romans, the Germans were used to it and employed it to their advantage. They also had the advantage of being accustomed to fighting hand-to-hand in a melee. Being much larger physically than their Roman counterparts, the Germans had a much longer reach with their spears. Severely shaken by the sudden presence of an enemy who should have been many miles away, the Roman soldiers began to flag. As nightfall brought an end to the fighting, defeat seemed certain.

Inspired by their early success, the Cherusci and their allies set to work in the dark to make life miserable for their adversaries. They diverted streams from the hills down into the low-lying area occupied by the Romans, destroying all the hard work accomplished during the day. To escape, the soldiers would have to start from scratch. Calm and stolid as ever, Cæcina remained unmoved at the sight of the reversals. Temperamentally the exact opposite of the impetuous Germanicus, he refused to budge from his commanded duty. Stubborn commitment was exactly what the situation required. Like any good engineer, Caecina used the tools he had been given. The only viable option he saw was to maintain his position until the wounded could be evacuated and the greater part of his army moved to a place of safety. As long as the Germans could be kept in the hills, the Romans could make their way along the remains of the Long Bridges. This would not permit them to bring their heavy baggage with them, but the army itself would be saved.

The Romans Retreat

Between the hills and the causeway along the edge of the swamp was a small area of flat ground, enough to form a thin line of battle. Cæcina put the 1st Legion in the post of honor, the vanguard, directly in front of the hills, where they would be the obvious target of any assault. The 5th Legion was placed on the right flank, the 21st Legion on the left. The 20th was put in reserve to hold off any pursuit. Now all they could do was wait.

Even if the Romans had not been kept awake by their anxiety, the shouts, singing, and celebrations of the Germans would have kept them from sleeping. Those few who did get some sleep were plagued by nightmares. Many of the legionaries had heard detailed descriptions of the horrors suffered by their comrades six years before—not to mention the fact that they had recently visited the site itself. The current situation was much too close for comfort to the earlier slaughter. Nor were the similarities lost on Cæcina. He too had a nightmare in which he saw Varus, covered with blood, rising up out of the swamp and calling to him. Varus held out his hand, either in supplication, friendship, or warning, but he was rebuffed by Cæcina, who did not want the slightest hint of Varus’s ill luck rubbing off on him.

At first light, the 5th and 21st Legions withdrew from their positions on the Roman flanks. Not willing to sacrifice themselves merely to buy time for the rest of the army, the legions took up positions on a small, level space beyond the swamp, with the 1st Legion squarely between them and the hills where the Germans lurked. From a relatively secure situation, the Roman position was now wide open to attack. Assuming the move to be some sort of trick on the part of the Roman commander, Arminius did not attack immediately. Observing the enemy’s heavy baggage and equipment mired down in the mud and rolled over into ditches, he now showed himself, but still refrained from launching an attack. The Romans attempted to regroup and cover their exposed flanks, but the situation quickly dissolved into chaos. Cohorts and maniples became entangled with one another, and individuals began abandoning their places in the line, intent only on securing their safety.

Seizing the opportunity, Arminius finally ordered an attack. At the head of a picked force of shock troops, the Cherusci chieftain screamed out a defiant challenge, warning the Romans that another of their armies had gotten itself into the same trap as the doomed Varus at Teutoburgerwald. As if to prove his boast, the Germans broke through the Roman line and began wreaking havoc, making the horses their special target. The animals, panicking at the smell of their own blood and that of their masters, bolted and spread even more confusion, trampling the fallen and becoming mired in the swamp. Meanwhile, German archers kept up a heavy fire, preventing the standard-bearers from bringing up the eagles. The Roman troops had no obvious rallying point. Cæcina was everywhere, trying to keep the line together, until his horse was killed under him. The Germans immediately moved in to capture him, but the 1st Legion arrived on the scene in the nick of time and rescued their commander.

Cæcina Reestablishes his Camp

Cæcina ordered an immediate withdrawal. Fortunately for the Romans, the Germanic tribesmen were more interested in gathering loot than in pursuing their enemies. As night drew near, Cæcina and his army forced their way back onto solid ground. A camp needed to be built, and most of the necessary equipment had been lost, but Caecina, imaginative to the last, managed to make do with what was at hand. Sod was cut and earthworks thrown up, a proper Roman camp finally taking shape while the pickets of the 20th Legion kept careful watch.

Most of the men still had no tents, and there were no medical supplies to assist the wounded. Rations, for the most part, had been spoiled by their soaking in filth and blood. Men sat around their miserable fires and predicted their own deaths on the morrow. A horse broke loose and ran through the camp, causing a rapidly spreading rumor that the Germans were once again upon them. The soldiers made a rush for the main gate, positioned strategically on the side away from any expected attack. Realizing that the reported attack had no basis in reality, Cæcina attempted to restore order. He threw himself across the main gate, blocking the opening with his body. Not even the panicky soldiers were so desperate as to trample their own commander in their haste to escape. They halted, and the tribunes and senior centurions eventually persuaded the men that it was a false alarm.

The near disaster had a beneficial effect. Cæcina collected the men in front of his headquarters and made a speech. He reminded them that the only way to survive was to fight, and the only way to fight was to make careful plans and stick to them. Nodding their heads in shamed agreement, the soldiers listened. The ordinarily stolid commander had sufficient eloquence to persuade the men to stay inside their defenses until the enemy actually approached. At that point, the entire force would break out as one and make straight for the Rhine. If they ran away again as they had just attempted, they would only meet their unfortunate predecessors’ fate in the same hideous forests and dismal swamps.

Cæcina collected the remaining horses belonging to the tribunes and legates and, starting with his own, assigned them to the best fighters in the army. They would provide the sharp edge of a wedge that would break through the German line in the event of an actual attack, followed by the regular legions.

Revenge for Teutoburgerwald

The German commander had his own problems. As a popular leader, Arminius could not simply order his chiefs and men to do as he wished—he had to persuade. His plan, consistent with his Roman military training, was to wait for the enemy to begin its march the next day, for they did not have the supplies or time to outlast the Germans in a siege. The Germans would then be able to drive, by sheer force of numbers, the legions into the swamp, where they would be destroyed. It would be Teutoburgerwald all over again.

Inguiomerus, Arminius’s paternal uncle, had a different view of the matter. The right way to proceed was in traditional fashion, he believed, surrounding the enemy camp and attacking on all sides simultaneously. This would result in more prisoners to enslave and more loot to be taken. The majority of the Germans favored Inguiomerus’s plan. At first light, the Germans started filling in some ditches, threw bridges across others, and began swarming up the unguarded earthworks surrounding the Roman camp. Reaching the top of the embankments, the Germans were encouraged by the sight of a few Roman soldiers milling about in apparent fear and confusion. Victory was once more in their grasp. With joyous shouts they poured down into the camp.

Once the bulk of the German army was deep in the camp, trumpets rang out for the Roman cohorts to attack in turn. Letting loose with their own shouts, the Romans sprang from their hiding places and fell on the German rear. Calling out “No woods or swamps here!” and “Fair field, fair chance!” the men of the Legion began mowing down the enemy without mercy. The Germans, egged on by their leaders and enflamed by their almost unbroken stream of recent victories, had committed the worst blunder that soldiers could make—they had grown overconfident. In light of the previous day’s events, they had expected to meet an undisciplined horde of frightened, defeated, and poorly armed men. Instead, the terrifying sight of the Roman war machine was bearing down on them from behind, while their presumed victims ceased their aimless activity and began grimly to complete the encirclement. The attackers were now the attacked.

German initiative completely disappeared. Expecting an easy victory, they had fallen into the same sort of trap the Romans had encountered six years earlier. The ensuing slaughter was also the same. The Germans were nearly wiped out, although most of their leaders managed to escape. Arminius, probably with an inkling of what would happen when his tribesmen rejected his carefully made plan, escaped without a scratch, His uncle Inguiomerus was not so lucky. As instigator of the battle plan, it was up to him to lead the attack personally. He was badly wounded.

The slaughter of the Germans went on for the rest of the day. Some of the tribesmen managed to escape from the death trap in the Roman camp, only to be pinned against the swamp. There the Romans exacted a bloody revenge for Teutoburgerwald.

It was not until night fell that the Romans returned to camp. They still had no food, no supplies, and little equipment, and many were more seriously wounded than before. But as the historian Tacitus later remarked, “They had their cure, nourishment, restorative, everything in one—victory.”

Germanicus’ Reception in Rome

Viewed objectively, Germanicus had not acted wisely in his short but intense campaign across the Rhine. He had endangered the Republic at a time when things were just beginning to return to normal by undertaking an expensive and rash campaign with no practical or achievable result other than personal glory. He then thoughtlessly put four of his legions in an untenable situation, leaving Cæcina and his men at the mercy of Arminius. But the biggest disaster of the entire campaign was yet to come—and it was not even at the hands of the Germans.

While Cæcina was holding off Arminius in the swamps east of the Rhine, Germanicus had continued his withdrawal by ship up the Ems River. He quickly reached the mouth where the Ems emptied into the North Sea. To lighten the burden of the vessels, Germanicus turned over the 2nd and the 14th Legions to Publius Vitellius, whom he ordered to proceed the rest of the way by land, following the shoreline into Frisia. Germanicus was worried, in light of the recent drought, that the draft of the vessels would not permit passage through shallow water or low tide if they were too heavily laden. Vitellius at first made rapid progress. Then, on the ides of September, a terrible storm roared off the North Sea. Wind and rain hammered the Roman column and turned the countryside into a trackless swamp. Inundated by surging waves, men drowned outright or were sucked under and trampled by the feet of their fellow soldiers and pack animals. Survivors struggled through water that reached their necks in some places.

Finally, Vitellius and his men managed to make their way to higher ground inland, without fire, food, clothing, or shelter. The losses were appalling. Virtually the whole of Vitellius’s command was wiped out in less than an hour. The waters receded when daylight came, and the survivors made their way to an estuary of the Ems, where they found Germanicus and the rest of the fleet. Ingloriously, they returned to Roman soil.

Tiberius was understandably angry with his adopted son. He immediately relieved Germanicus of command and recalled him to Rome. Had not the emperor genuinely loved his brother Drusus’s son, the punishment might have been far more serious. As it was, Germanicus was greeted as a hero upon his return. Demonstrating anew the vagaries of public opinion, the younger man continued to enjoy almost complete popular support, while Tiberius incurred widespread censure for his supposed jealousy of his dashing heir. Such was the life of a Roman emperor, and such was the continuing power of the ever-bothersome Germans to make manifest trouble whenever and wherever they chose.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments