By Michael D. Hull

They were two unlikely looking warriors, yet their fateful friendship and shared leadership ensured the Allied victory in World War II and laid the groundwork for peace.

Winston Spencer Churchill, the British prime minister, was short, chubby, pink, and “cuddly.” He lectured rather than listened, talked endlessly about everything, did much of his work in bed, and was “alcohol-dependent.” Said a soldier from the ranks during a formal inspection,

Winston Spencer Churchill, the British prime minister, was short, chubby, pink, and “cuddly.” He lectured rather than listened, talked endlessly about everything, did much of his work in bed, and was “alcohol-dependent.” Said a soldier from the ranks during a formal inspection,

“He’s a pugnacious-looking bastard.”

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the American president from 1933 to 1945, once had the lean body and dash of a Hollywood leading man. But, after the ravages of polio in 1921 and subsequent confinement to a wheelchair for 20 years, all that remained was a leonine head and broad torso attached to a pair of wasted legs. He could not walk or stand unaided, and Italian dictator Benito Mussolini privately mocked him as “that cripple.”

Yet, outward appearances notwithstanding, Churchill and Roosevelt were men of rare courage, humanity, and vision; they were the two outstanding leaders of the 20th century. They were at the same time both idealists yet realists, consistent yet unpredictable, and calculating yet impulsive, as shown in this penetrating dual portrait, Forged in War (Ivan R. Dee, Chicago, 2003, 352 pp., 12 photographs, notes, index, $18.95, softcover), by Warren F. Kimball, the Robert Treat professor of history at Rutgers University. Literate, lively, and informed, it is a thoughtful analysis of the remarkable relationship between the Marlborough scion and the Hudson Valley patrician, both defenders of freedom who stood resolute against tyranny.

The two men were not chosen by committee but rose to wartime power through the political process. From FDR’s unprecedented peacetime draft to Churchill’s key role in the pivotal Battle of Britain, and from the Atlantic Charter conference to Yalta, Kimball’s riveting narrative sets their leadership within the context of the great global struggle.

The two leaders who worked with remarkable affinity for more than five years were drawn together by circumstances rather than by personalities, the author points out, and the union was not all smooth sailing. Churchill admitted ruefully, “…in the White House, I’m taken for a Victorian Tory,” while FDR distrusted the prime minister’s unabashed imperialistic ideals. And there were strategic differences that strained the fabric of the Allied alliance, such as the second front, the Mediterranean theater, and the stormy relationship with Soviet Marshal Josef Stalin.

But, as Kimball makes abundantly clear, nothing could shake the friendship that saved Western civilization. Immensely documented, balanced, and intelligent, this is a most rewarding study.

Recent and Recommended

December 8, 1941 by William H. Bartsch, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 2003, 557 pp., 44 photographs, appendices, notes, index, $40, hardcover.

December 8, 1941 by William H. Bartsch, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 2003, 557 pp., 44 photographs, appendices, notes, index, $40, hardcover.

Ten hours after the December 7, 1941, attack on the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, an even more devastating blow to American arms was struck 4,500 miles to the west.

At 12:35 am on December 8, an armada of 196 Japanese Navy bombers and fighters pounced on the Army Air Forces bases at Clark and Iba Fields on Luzon in the Philippine Islands and destroyed a dozen of the U.S. Far East Air Force’s 19 B-17 bombers and 34 of its 92 P-40E fighters on the ground. In one stroke, the largest force of B-17s outside the United States was crippled and the major American obstacle to Japan’s southward advance removed.

Some high-ranking officers and historians have maintained that, compared to the strategic disaster at Clark Field, the loss of five battleships at Pearl Harbor had relatively little influence on the course of the Pacific War. Then-Lt. Gen. Douglas A. MacArthur, the Army commander in the Philippines, who had been informed of the Pearl Harbor attack and alerted to the likelihood of a strike on his forces, had boasted earlier in 1941, “The inability of an enemy to launch his air attack on these islands is our greatest security.”

Despite its significance for Allied fortunes in the Far East, MacArthur’s blunder in his beloved Philippines, where he overestimated Filipino readiness for war and woefully underestimated Japanese capabilities, has never been accorded full treatment. But aviation writer William Bartsch now fills the historical gap impressively, drawing on 25 years’ meticulous research and interviews with many veterans of the December 8 attack, including survivors of the raids on Clark and Iba Fields.

In an immensely detailed, well paced, and balanced narrative, he describes minute by minute the attacks on the air bases, preceded by the belated, hurried U.S. buildup of air power in the islands after July 1941, and enemy preparations for their “other Pearl Harbor.” Bartsch has done an astounding job on what is sure to become the definitive work on one of the darkest days in American history.

He explains that, unlike the Pearl Harbor aftermath, there was no rush to find scapegoats for the December 8 fiasco. No official investigation was ever launched to allocate responsibility because the Philippines were a war zone, while General MacArthur was too much of a national hero to be held accountable. It would have been inappropriate to call him to Washington to testify while he was engaged in a campaign.

Bartsch is also the author of Doomed at the Start, a study of U.S. pursuit pilots in the Philippines in 1941-42.

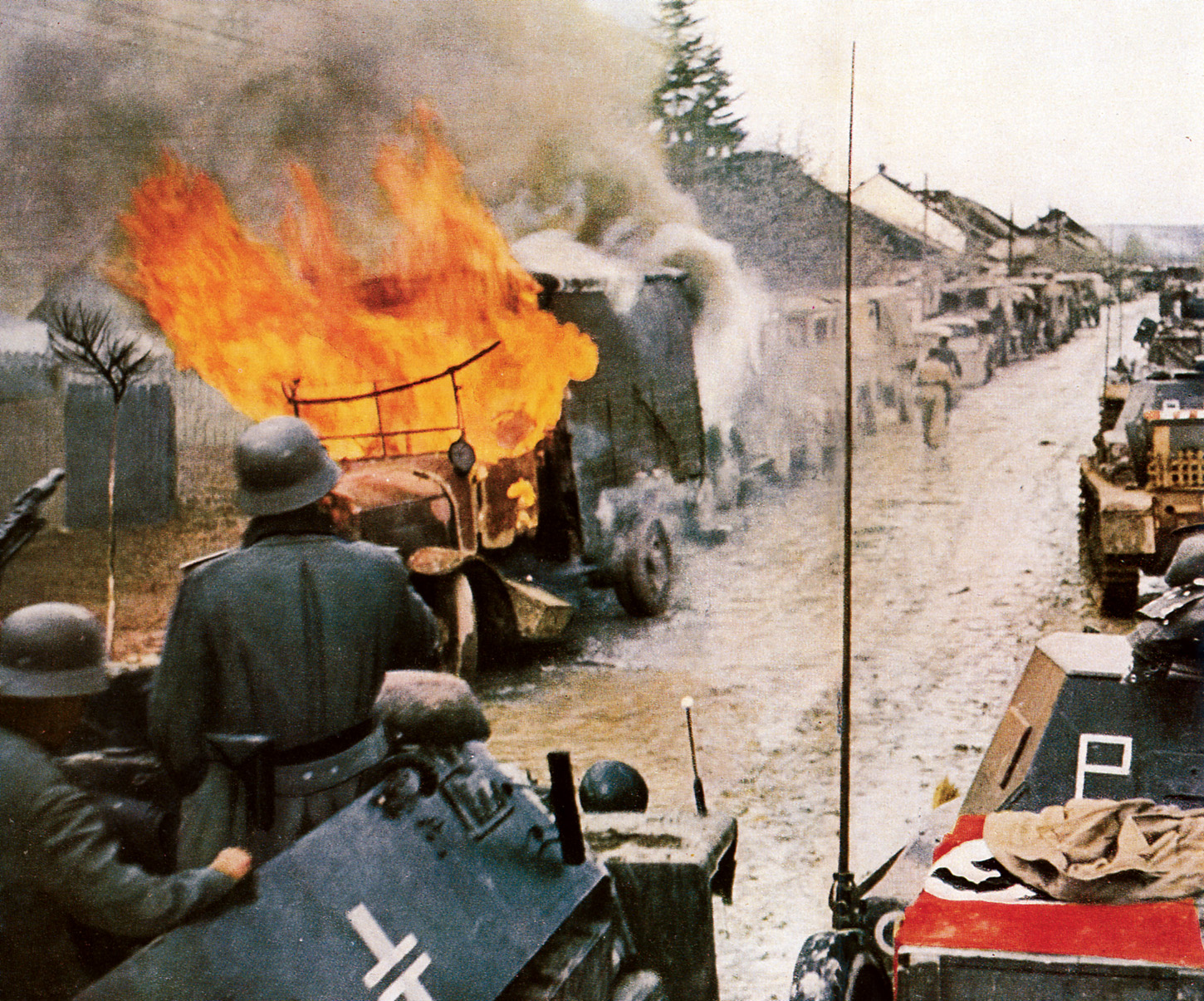

German Armored Warfare of World War II by Ian Baxter, Casemate, Havertown, Pa., 2003, 224 pp., 300 photographs, appendix, index, $34.95, hardcover.

German Armored Warfare of World War II by Ian Baxter, Casemate, Havertown, Pa., 2003, 224 pp., 300 photographs, appendix, index, $34.95, hardcover.

A new word entered the lexicon of warfare when German panzer, artillery, and infantry columns started their fast-moving offensive into Holland and Belgium on May 10, 1940: “blitzkrieg.”

The idea for the steel-tipped strategy had come from British theorists Captain Basil Liddell Hart and Major Gen. J.F.C. Fuller in the 1930s, and was readily adopted by the German High Command when the British, who had invented the tank and created the world’s first armored corps, were slow to develop it. Blitzkrieg was the opening act of a scourge that would devastate much of Europe during World War II.

A graphic insight into the German armored forces of 1939-45 is provided in this volume by Ian Baxter, a British historian noted for 20 previous books on Nazi Germany. Complementing an impressive gallery of previously unpublished photographs, he details the panzer divisions—main and light battle tanks, assault guns, tank destroyers, artillery, reconnaissance units, panzergrenadiers (armored infantry), and support vehicles—as they fought at the Meuse, Amiens, Gela, Villers-Bocage, Caen, and St.-Vith in the West, Beda Fomm, El Alamein, Mareth, and Tripoli in the desert of North Africa, and Kharkov, Stalingrad, and Kursk on the Russian steppes.

With unerring scholarship and insight, the author examines the Panzerwaffe, one of the most effective and fearsome fighting organizations in history, its men, weapons, tactics, and hard-fought actions from the early triumphs in the Low Countries to its demise in the rubble of Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich in the spring of 1945. This is a stunning work.

Medal of Honor: Portraits of Valor Beyond the Call of Duty by Nick Del Calzo and Peter Collier, Artisan, New York, 2003, 244 pp., 250 photographs, glossary, $40, hardcover.

Medal of Honor: Portraits of Valor Beyond the Call of Duty by Nick Del Calzo and Peter Collier, Artisan, New York, 2003, 244 pp., 250 photographs, glossary, $40, hardcover.

For television news anchorman Tom Brokaw, the meaning of valor as exemplified by the Medal of Honor re-entered his life in June 1984, when he went to Normandy to make a documentary on the 40th anniversary of D-day.

One of his subjects was Gino Merli of Peckville, Pa., a former pfc. in the 18th Infantry Regiment of the 1st Infantry Division, who had waded ashore at Omaha Beach and later been awarded the nation’s highest decoration for heroism when his machine-gun position near Sars-la-Bruyere, Belgium, was overrun by a superior German force on September 4, 1944. After being wounded in the Battle of the Bulge, Merli received the coveted blue ribbon from President Harry S. Truman on June 15, 1945.

That day spent with Merli led Brokaw to write his best-selling book, The Greatest Generation.

Merli is one of 117 surviving Medal of Honor winners showcased in this collection of essays, personal histories, and stunning portraits that salutes the uncommon strength and dedication shown by the 3,440 men, from all walks of life and in all the services, who have worn the decoration in America’s wars during and since the Civil War.

The text is by Peter Collier, the best-selling author of books on the Rockefeller and Kennedy families, and the illustrations are by award-winning photographer Nick Del Calzo. The introduction is by Brokaw, the foreword by Senator John McCain (R–Arizona), and a letter by former President George H.W. Bush is included.

Covering World War II and the Korean and Vietnam Wars, these profiles provide living testimony to the best of what Sir Winston Churchill called “the American spirit.” In a time of commercialized and specious patriotism, this handsome volume reminds us of the real meaning of valor and places more recent, media-hyped conflicts into perspective.

Pacific Alamo by John Wukovits, New American Library, New York, 2003, 308 pp., 42 photographs, maps, notes, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Pacific Alamo by John Wukovits, New American Library, New York, 2003, 308 pp., 42 photographs, maps, notes, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Through the grim days following the devastating Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt at least had reports of the gallant defense of Wake Island to brighten his day. It was like another Thermopylae, Alamo, or Rorke’s Drift to lift the spirits of his shaken people.

But when the Navy Department learned that Major James P.S. Devereux’s 1st Marine Defense Battalion and a handful of construction workers had been overwhelmed by a Japanese landing force, the president was devastated. He called the news “worse than Pearl Harbor,” and castigated the Navy for the misguided recall of Rear Adm. William S. Pye’s relief expedition, which turned back from Wake Island.

After signing a Presidential Unit Citation for the Marine battalion, Roosevelt paid stirring tribute to the Wake defenders in his State of the Union address to Congress on January 6, 1942: “When the survivors of that great fight are liberated and restored to their homes, they will learn that 130 million of their fellow citizens have been inspired to render their own full share of service and sacrifice.”

As historian-biographer John Wukovits relates in his richly documented, measured, and rewarding study, America’s Alamo on the remote Pacific atoll inspired the people. Lines grew at recruiting offices, sales of war bonds mounted, and a new rallying cry resounded: “Remember Wake Island!” National morale soared as the fight was celebrated in newspapers, magazines, radio broadcasts, poems, comic books, a song, and a hurried but memorable Hollywood film starring Brian Donlevy, William Bendix, Robert Preston, Walter Abel, and Macdonald Carey.

After the Pearl Harbor attack, the fall of Guam, and the destruction of U.S. air power on the ground in the Philippines, the Wake Island saga redeemed national honor and handed America a blueprint for eventual victory, says the author. Several books on Wake Island have appeared in recent months, but this one is well worth reading. Besides weaving a vivid, hour-by-hour account of the three-week siege, Wukovits has fleshed in a wealth of human detail that brings to life the defenders, officers, gunnery sergeants, riflemen, aviators, and Dan Teters’s technicians and laborers. This is a sturdy tribute to one of America’s finest hours.

The Fall of France by Julian Jackson, Oxford University Press, New York, 2003, 274 pp., 29 illustrations, 11 maps, notes, index, $26, hardcover.

The Fall of France by Julian Jackson, Oxford University Press, New York, 2003, 274 pp., 29 illustrations, 11 maps, notes, index, $26, hardcover.

After visiting France in January 1940, General Edmund Ironside, Chief of the British Imperial General Staff, summed up his impressions of the French Army:

“We must have confidence in the French Army,” declared the burly, multilingual veteran of South Africa, Flanders, and North Russia. “It is the only thing in which we can have confidence. Our own army is just a little one, and we are dependent upon the French. All depends on the French Army, and we can do nothing about it.”

But the army he described was not the one that would face the German blitzkrieg five months later. After thrusting into the Low Countries on May 10, 1940, and subduing the Dutch and Belgians, Wehrmacht panzer and infantry formations wheeled southward, breached French defenses on the Aisne and Somme Rivers, and marched into Paris on June 14. Eight days later, the divided French government signed an armistice. The French were defeated in six weeks, and it was the most humiliating military disaster in their history.

But the fall of France, one of the pivotal and most debated moments of the 20th century, was not inevitable, says Julian Jackson, professor of French history at the University of Swansea, Wales. If the German offensive had failed, the war might have ended right there. Yet, as it was, the French collapse ultimately drew much of the world into war. Debunking previous misconceptions that the German Army was vastly superior, the author points out that the French Army was fairly evenly matched with it early in 1940, and was better armed in many areas. The vaunted doctrine of blitzkrieg, he argues, was as much theory as reality; few German units were fully mechanized, and the Wehrmacht was heavily dependent on horse transport.

The French Army had many strengths, Jackson writes, and its more experienced troops did well in action. But few of its commanders had taken any advantage of such innovations as mobile warfare (Charles de Gaulle was an exception), and their thinking was still mired in the trenches of 1914-18. Like its government, the French Army was uncoordinated, rent by infighting, and incapable of mustering nationwide resistance.

In a remarkable work of insight and sound reasoning, Jackson recreates graphically the tumultuous six weeks that stripped France of its former glory, left the British standing alone, and changed the course of the 20th century. The tragic capitulation stunned the world. As French writer-aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupery recalled, “Surely, I must be dreaming.”

Jackson’s study is fresh, sharp, and engaging.

The Impact of Nazism edited by Alan E. Steinweis and Daniel E. Rogers, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, 2003, 260 pp., index, $49.95, hardcover.

The Impact of Nazism edited by Alan E. Steinweis and Daniel E. Rogers, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, 2003, 260 pp., index, $49.95, hardcover.

In Thomas Wolfe’s posthumously published 1939 novel, The Web and the Rock, the hero pays a visit to the famous Munich Oktoberfest. He is enjoying the food, the dark and heavy beer, and the merriment around him when suddenly the scene and his perception begin to tilt, and he experiences a dreamlike sequence. The beer-drinking and singing crowd assumes a deeply threatening character.

“It seemed to (him) that nothing on earth could resist them—that they must smash whatever they came against,” wrote Wolfe. “He understood now why other nations feared them so … He felt as if he had dreamed and awakened in a strange, barbaric forest to find a ring of savage, barbaric faces bent down above him: blond-braided, blond-mustached, they leaned upon their mighty spear staves, rested on their shields of toughened hide, as they looked down. And he was surrounded by them; there was no escape.”

Wolfe captured in dramatic literary scenes the coexistence of contradictory feelings toward the Germans, as Michaela Honicke Moore points out in this collection of 13 scholarly, penetrating essays on the phenomenon and impact of Nazism in the 20th century. In an essay on National Socialism, Miss Moore notes that Wolfe, who died before Adolf Hitler started World War II, understood the evil he described as being part of human nature—German human nature. “Hitler,” Wolfe believed, “was a recrudescence of an old barbarism.”

Illuminating and provocative, the essays in this book address many aspects of Nazism, including the origins and character of antisemitism and anti-Slav policies, the Nazification of the Prussian military high command, Third Reich decision-making, Hitler’s leadership, German scholars’ roles in promoting persecution tactics, the actions of German police in the occupation of eastern Europe and the Jewish genocide, and Nazism in the war’s aftermath. There is a wealth of intelligent insight here into the enigmatic race that produced Beethoven, Goethe, Bach, Handel, Schiller, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Wagner, Brecht, Einstein—and gas chambers.

Steinweis is an associate professor of history and Judaic studies at the University of Nebraska, and Rogers is an associate professor at the University of South Alabama. Both have previously written books on Nazi Germany.

The National Guard by Michael D. Doubler and John W. Listman Jr., Brassey’s, Dulles, Va., 2003, 191 pp., 450 photographs, appendix, index, $29.95, hardcover.

The National Guard by Michael D. Doubler and John W. Listman Jr., Brassey’s, Dulles, Va., 2003, 191 pp., 450 photographs, appendix, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Major General Charles W. Ryder’s 34th Infantry Division was the first U.S. combat division to be sent overseas following the Pearl Harbor attack.

The “Red Bull” Division sailed from New York to Northern Ireland in January 1942 to relieve British Army units and start training for the planned Allied invasion of Northwest Europe. But, reflecting strategic decisions, the 34th was reassigned to the invasion of North Africa on November 8, 1942. Landing in Algeria, it helped to defeat the Afrika Korps in Tunisia, suffered 4,200 casualties, and went on to distinguish itself in Italy.

The 34th was one of many National Guard divisions that fought in the Mediterranean, Pacific, and European theaters in World War II and whose valiant service is chronicled in this handsome history of America’s Minutemen by Michael Doubler, a retired Army Guard colonel, and John Listman, a former Guard chief warrant officer. Briskly written and lavishly illustrated, it is an inspirational record of 400 years’ service to the nation and the preservation of freedom.

From the 1607 defense of the Jamestown settlement to Omaha Beach, the story of America’s oldest military institution rooted in the English tradition of militia service is charted thoroughly. The Guard’s contributions in American history have been as strong as those of the Long Gray Line, say Doubler and Listman.

The authors trace the Guard’s greatest challenge, World War II, by detailing the actions of the various divisions: the 45th “Thunderbirds” in Sicily; the 36th “Texas” at the disastrous Rapido River crossing and Southern France; the 29th enduring the Omaha Beach debacle; the 30th “Old Hickory” at Mortain; the 35th “Santa Fe” at St. Lo and the River Elbe; the 28th “Bloody Bucket” in the Hurtgen Forest and the Bulge; the 26th “Yankee” at Metz and Bastogne; the latecomer 44th breaching the Siegfried Line; and the 10 divisions playing a key role in the Pacific, from Guadalcanal to Okinawa.

Rich in fascinating vignettes, this is a highly readable volume. It covers both the Army Guard and the Air National Guard.

The World War II Combat Film by Jeanine Basinger, Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, Conn., 2003, 377 pp., 38 photographs, notes, indexes, $22.95, softcover.

The World War II Combat Film by Jeanine Basinger, Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, Conn., 2003, 377 pp., 38 photographs, notes, indexes, $22.95, softcover.

Any ranking list of the best motion pictures about World War II would have to include Henry King’s Twelve O’Clock High, Noel Coward’s In Which We Serve, Allan Dwan’s Sands of Iwo Jima, John Ford’s They Were Expendable, Tay Garnett’s Bataan, Lloyd Bacon’s Wake Island, Anthony Asquith’s The Way to the Stars (Johnny in the Clouds), Carol Reed’s The Way Ahead (Immortal Battalion), Darryl F. Zanuck’s The Longest Day, David Lean’s The Bridge on the River Kwai, Lewis Seiler’s Guadalcanal Diary, Richard Attenborough’s A Bridge Too Far, and William Wellman’s masterpiece, Battleground.

Released in black and white in 1949 by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Battleground focuses on a company of the U.S. 101st Airborne Division at the siege of Bastogne in December 1944. Gritty and inspiring, the film was scripted by Robert Pirosh, himself a veteran of Bastogne. The cast is headed by Van Johnson, John Hodiak, George Murphy, Ricardo Montalban, Denise Darcel, Marshall Thompson, and James Whitmore in his memorable first role as grizzled Sergeant Kinney.

A major critical and commercial success, Wellman’s film endures because it is an honest celebration of the ordinary infantryman, says Jeanine Basinger, chairwoman of the film studies department at Wesleyan University, in her exhaustive analysis of World War II cinema. A work of wider breadth and scope than previous such books, it is intriguing and perceptive; a phenomenal achievement, even though she has chosen to include such recent abominations as Saving Private Ryan and Pearl Harbor.

She explains the wisdom shown by the makers of Battleground in their quest for realism because they realized that their audiences would include World War II veterans. Superbly written, edited, acted, and photographed, the film’s look, fog, snow, and forest gloom, seems real. And yet Wellman shot it on a Culver City backlot. Battleground showed Americans that they could be proud they had helped to win the war, says the author. The film “healed, united, and entertained.”

Basinger studied more than a thousand war pictures in a five-year period to research this book. With extensive knowledge and a brisk approach, she analyzes the genre of war films and compares it with other types, such as westerns, musicals, and comedies. The author’s enthusiasm shows through to make this a delightful book.

, Sourcebooks, Naperville, Ill., 2003, 286 pp., photographs, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

, Sourcebooks, Naperville, Ill., 2003, 286 pp., photographs, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Late on Saturday night, August 24, 1940, Edward Roscoe Murrow stood outside historic St. Martin-in-the-Fields Church at the northeastern corner of Trafalgar Square in London. He was the chief European correspondent for the Columbia Broadcasting System, and he was reporting from a city at war.

The Battle of Britain was raging, and American radio listeners 3,000 miles away would soon be hearing the sounds of German bombers droning overhead, air raid sirens wailing, and the unhurried footsteps of Londoners walking the blacked-out streets. “More searchlights come into action,” reported the tall, earnest newsman in a resonant baritone voice. “You see them reach straight up into the sky, and occasionally they catch a cloud and seem to splash on the bottom of it.”

In the following months, the fearless Murrow regaled his audience with live broadcasts from London rooftops as bombs fell and great fires lit up the city. Murrow refused to seek refuge in air raid shelters because he did not want to lose his nerve, and his newscasts played a key role in stirring up American support for Great Britain, then standing alone against Nazism.

One of the great journalists of the 20th century, the eloquent, chain-smoking Murrow went on to cover the Normandy landings, Operation Market-Garden, and the liberation of Buchenwald. His unforgettable reports, and those of several other “Murrow Boys,” make up this dramatic and riveting reporters’ record of World War II. It is accompanied by a compact disc narrated by CBS anchorman Dan Rather, and is a unique history.

Among the other broadcasters featured are William L. Shirer reporting on the French surrender at Compiegne; Cecil Brown on the sinking of HMS Repulse; Larry LeSueur on the liberation of Paris; Charles Collingwood on the Allied occupation of Algiers; Winston Burdett on the Afrika Korps’ retreat in Tunisia; Richard C. Hottelet on street fighting in Aachen, and Howard K. Smith on the Allies’ Rhine crossing.

This remarkable volume constitutes a tribute to a band of crack journalists whose like we have not seen since. As Murrow himself modestly observed, “For a few brief years, a few men attempted to do an honest job of reporting under difficult and sometimes hazardous conditions, and they did not altogether fail.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments