By Roy Morris Jr.

William Bligh, like the title character in Woody Allen’s 1983 movie Zelig, seemed to turn up everywhere history was being made in the latter decades of the 18th century. Whether it was at the murder of English explorer William Cook on a windswept Hawaiian beach in 1779 or during the most famous mutiny in naval history, aboard HMS Bounty off the coast of Tahiti in 1789, William Bligh was there. And at the Battle of Camperdown in 1797, the boastful captain managed to alienate his fellow officers at the very moment of victory. It was consistent with Bligh’s less than pleasing personality, a personality that managed to obscure his very real virtues as a practical seaman and leader of men.

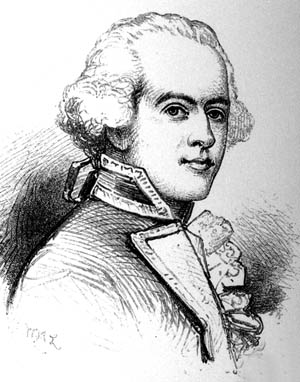

Bligh was a typical British sea dog of the age. Born near the great naval port of Plymouth in 1754, the son of a harbor master, he first went to sea as a captain’s cabin boy at the age of seven. As an “able seaman,” or officer in training, he sailed the West Indies aboard various ships before signing on as sailing master with the famous explorer and cartographer James Cook in 1776. Aboard Cook’s flagship, Resolution, Bligh first saw the island of Tahiti, which would loom large in his destiny.

After Cook’s death in Hawaii three years later, Bligh continued his career in the Royal Navy, rising to command the 220-ton cutter Bounty on an expedition to harvest and transport breadfruit trees from Tahiti. The savory-sounding fruit (which actually tastes like a boiled potato) was much prized as a foodstuff for Caribbean slaves. It takes several months for the fruit to mature, which was the beginning of Bligh’s downfall. While waiting to harvest the breadfruit, the captain gave his crew shore leave on Tahiti. Like sailors everywhere, the men more or less ran amok, taking native girlfriends, adopting informal beachwear, and slipping into lives of coconut-scarfing ease.

Not surprisingly, some of the men did not want to give up their newfound leisure. Led by midshipman Fletcher Christian, 18 of the crew mutinied when Bounty set off on her return voyage in April 1789. Taking control of the ship, the rebels marooned Bligh and a group of loyal sailors in Bounty’s lifeboat with a sextant, four cutlasses, and enough food and water to last a few days. Remarkably, Bligh managed to navigate the men to safety on the island of Timor, arriving with the loss of only one man (killed by natives) after a voyage of 47 days that covered more than 3,600 nautical miles.

Back in England, supporters of the mutineers—particularly Fletcher Christian’s disputatious family—spread rumors that Bligh had been overly abusive to his crew. In fact, the captain was less rigorous than most English commanders of the day, taking an untypical interest in the men’s health and hygiene. It was the beautiful women and sultry sea breezes of Tahiti, not Bligh’s studded cat-o’-nine-tails, that provoked the mutiny.

Restored to command, it would be Bligh’s unusual fate to become involved in two more mutinies during his career: the Navy-wide uprising at the Nore prior to the Battle of Camperdown, and a rebellion of Australian rum runners in New South Wales, where Bligh was serving as territorial governor. Nothing if not a survivor, Bligh weathered all three mutinies, but his historical reputation has unfairly cast him as an effete, out-of-touch martinet. His quick temper and tart tongue were largely to blame. As fellow officer J.C. Beaglehole noted, not unsympathetically: “Thin-skinned vanity was his curse through life. Bligh never learnt that you do not make friends of men by insulting them.” Or by turning them loose in a tropical paradise.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments