By William Be. Allmon

Of all the generals who fought on the Patriot side during the American Revolution, none was more renowned than New York City native William Alexander, better known to his contemporaries as “Lord Stirling.” Called a “great addition to the [Continental] army” by one contemporary, Stirling became one of George Washington’s ablest lieutenants. He never hesitated when it came time to choose between America and the British Empire—he was a rebel from the beginning.

“Heir to the Last Earl of Sterling”

Although he was not born an earl, Stirling’s origins were far from commonplace. His father, James Alexander, had supported the Jacobite rebellion of 1715 against King George I of England. After the rebellion collapsed in 1716, James Alexander fled to New York, where he became a lawyer and married a successful merchant named Mary Sprat. Their son William was born into respectable circumstances and a high social position on Christmas Day, 1726.

Doted on by his rich and successful parents, William received an excellent education in mathematics, surveying, astronomy, and general science. He fell into an easy working relationship in his mother’s retail business. Allowed a free rein by his parents in business, law, and society, William built his own fortune in trading and shipping, becoming a major in the New York militia in 1754. He married Sarah Livingston, the daughter of prominent colonial merchant Philip Livingston, and became increasingly involved in public affairs.

When the Seven Years’ War broke out between France and Great Britain, Royal Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts appointed Alexander his military secretary. Taking up his duties in 1755, Alexander assisted Shirley in planning and supplying a military expedition against French forts in western New York. After the campaign failed, Shirley was summoned back to London in July 1756 to account for his actions. Alexander loyally accompanied him to England and testified in Shirley’s behalf before the House of Commons. Despite his efforts, Shirley was removed from his post as governor of Massachusetts.

While living in England, Alexander reveled in the friendship of aristocrats such as the Duke of Argyle, William Pitt, George Greenville, the Earl of Bute, Henry Clinton, and Lord Shelburne. His embrace of high society was exemplified by his pursuit of the lapsed Scottish earldom of Stirling in 1757. In 1621, Charles I had awarded title to 10 million acres of North American land to the first Earl of Stirling, who was also named William Alexander. Henry Alexander, the fifth Earl of Stirling, had died without an heir. If Alexander could successfully become the sixth earl, he could lay claim to vast tracts of land. For three years, Alexander doggedly pursued proof of his claim to the title, but no link was found between his own ancestors and the fifth Earl of Stirling.

Eventually, Alexander’s solicitor, Andrew Stuart, located two old men who recalled local gossip that Alexander was related to John Alexander, the uncle of the first Earl of Stirling. Stuart presented the case before a jury in Edinburgh, Scotland, in March 1759. After listening to the evidence, the jury declared Alexander “the nearest male heir to the last Earl of Stirling” and recognized his claim to the earldom, “with all its estates and honors.”

“Friend of the Liberties of Mankind”

Despite the ruling, Alexander was still not a peer—he would have to petition the House of Lords for acceptance of his title. “What must I petition for?” Alexander wrote to Stuart in late 1759. “The foundation of all the precedents and petitions is removed in my case and I have no competition. It is hard to petition when I have nothing to ask for.” But with millions of acres in America at stake, he had no choice. On May 2, 1760, Alexander had the Earl of Holderness present his claim to the House of Lords, which referred the petition to the Lord’s Committee of Privileges. In the end, the petition languished for nearly two years before the committee ruled against Alexander, saying he ought to be “considered as having no right to the said title.”

Before the judgment was handed down, Alexander sailed for New York after five years in England. Undeterred by the snub from the peers, Alexander continued to insist that he was the sixth Earl of Stirling, and was addressed as “Lord Stirling” by his friends and family. Now a man of wealth and social prominence, he built a mansion near Basking Ridge, New Jersey, and settled into the life of a country squire. He remained a highly respected citizen, serving on the councils in New York and New Jersey, supporting organizations such as King’s College in Columbia, New York, and promoting colonial farming, manufacturing, and mining. The rising tensions between Great Britain and its American colonies made little impression on Stirling. With his apparently pro-British activities, many colonists believed that he would side with London on the question of colonial independence.

Instead, when the American Revolution began in April 1775, Stirling declared himself openly to be a “friend of the liberties of mankind” and joined the American cause. His overriding reason for supporting the patriots, he wrote to New Jersey’s loyalist governor, William Franklin, the son of Benjamin Franklin, was King George III’s rejection of the colonists “most humble, dutiful and respectful petitions to the throne.” For the rest of the Revolution, Stirling’s support never wavered.

An Officer in the Continental Army

On November 7, 1775, Stirling was commissioned a colonel in the Continental Army and took command of the 1st New Jersey Regiment, which drilled throughout the fall and winter of 1775-1776 at Elizabethtown while the main American army besieged British forces in Boston. On January 3, Stirling and 120 civilian volunteers captured the British transport Blue Mountain Valley, along with her crew, her cargo of 107 tons of coal, 100 butts of porter, 15 tons of potatoes, 112 bushels of beans, 110 casks of sauerkraut, and eight hogs. The Continental Congress commended Stirling for his “alertness, activity and good conduct.”

In early February 1776, Maj. Gen. Charles Lee, commanding Continental forces in New York City, ordered Stirling to report with his 500-man regiment. Moving quickly, Stirling and the 1st New Jersey arrived on February 6, and Lee set them to work fortifying the city. On March 1, Stirling was promoted to brigadier general on the recommendation of his friend, Congressman James Dunne. Delighted by the honor, Stirling assured Congress that he would do everything within his power to “merit the approbation of his countrymen.”

Stirling’s Command in New York

Stirling took command of American troops in New York on March 7, when Lee left for Charleston, South Carolina. “His lordship is active and distinct,” Lee wrote to Washington. “He will acquit himself well.” Stirling built forts along the Hudson River and Brooklyn Heights on Long Island. Confident that his defenses could withstand a British attack, Stirling wrote to Washington, “I could wish General Howe would come here in preference to any other spot in America. Then I would have the honor of serving under your immediate command.” Stirling’s wish came true on April 13, 1776, when Washington assumed command of the 28,500 Continental soldiers defending New York. He gave Stirling command of the Army’s 4th Brigade, made up of regiments from Maryland and Delaware.

The danger facing Washington’s army became clear on July 2, when 32,000 British and Hessian troops commanded by General Sir William Howe and supported by 500 ships and barges, landed on Staten Island. It was an armed force larger than the entire population of New York or Philadelphia. Howe immediately ferried 20,000 troops from Staten Island to Long Island to confront Washington’s army deployed on three main roads leading inland.

On August 25, Stirling’s brigade joined Maj. Gen. Israel Putnam’s 8,000 troops on Long Island, covering the Gowanus Road on the right flank, with Maj. Gen. John Sullivan’s brigade guarding the central Flatbush Road and Colonel Samuel Miles’s brigade watching the Bedford Road to the left. Concerned about the unguarded Jamaica Road on the extreme left flank, Stirling paid five officers $50 each to warn of a British advance from that direction. Expecting Howe to advance up the three main roads, Putnam and Sullivan saw no need for concern.

Captured and Exchanged

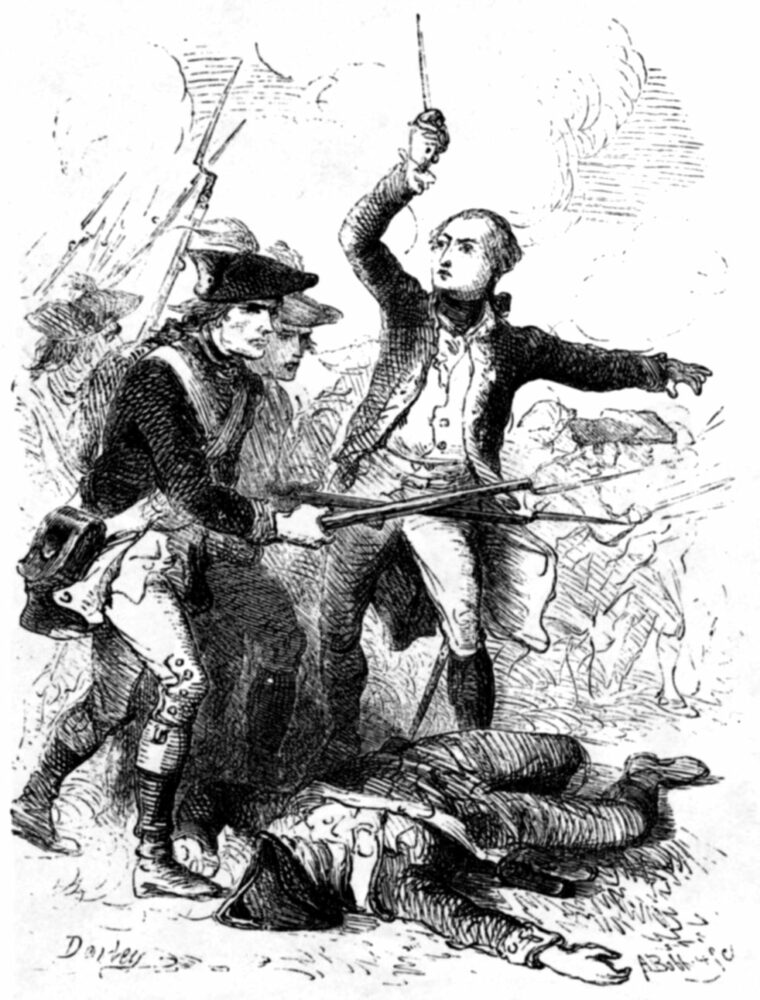

Stirling was asleep in Putnam’s headquarters at 3 am on August 26 when he learned that the British were advancing on his position. Rejoining his brigade, Stirling soon had Colonel William Smallwood’s Maryland Regiment and Colonel John Haslett’s Delaware Regiment marching through the early-morning darkness. At 6 am, a half mile from the Red Lion Tavern on Gowanus Road, Stirling joined Colonel Samuel Atlee’s regiment, which was skirmishing with 5,000 British troops led by Maj. Gen. James Grant. For the next four hours, although outnumbered 4-to-1, Stirling repulsed Grant’s regulars. Meanwhile, Howe moved up the Jamaica Road, outflanking the patriot position, falling on both Miles’s and Sullivan’s brigade and crushing the American center.

With 10,000 British and German troops closing in, Stirling ordered his men to retreat, while he and 250 Marylanders led by Major Mordecai Gist counterattacked. Stirling, said one observer, “fought like a wolf,” leading charge after charge while the rest of his brigade escaped. Realizing the battle was hopeless, Stirling ordered his men to scatter, with British and Hessians in full pursuit. It would be useless to attempt his own escape, Stirling recalled, and he surrendered his sword to Hessian General Philip von Heister, joining Sullivan and 1,079 American prisoners. Despite his capture, Stirling had fought well in his first battle.

That night, Stirling and Sullivan were taken aboard Admiral Richard Howe’s flagship, HMS Eagle, and treated with great courtesy in an effort to get them to take peace proposals to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Stirling, unconvinced of the admiral’s good intentions, refused. In the end, Sullivan alone took Howe’s proposals to Congress while Stirling remained in British custody.

On September 6, the Americans offered to exchange British Brig. Gen. Donald McDonald for Stirling. William Howe instead offered to exchange “Brigadier General Alexander, commonly called Lord Stirling,” for Governor Monfort Brown of Providence Island, who had been captured in an American naval raid on the West Indies. Washington agreed, and Stirling was exchanged on October 6.

Stirling at the Battle of Trenton

Rejoining the army the next day, Stirling took command of a brigade formerly led by Brig. Gen. Thomas Mifflin, Washington’s adjutant, and joined the retreat from New York, across New Jersey, and into Pennsylvania. By December 16, after serving as rear guard while the rest of the army crossed the Delaware River, Stirling’s 505 soldiers crossed into Pennsylvania and rejoined Washington’s army. On Christmas Eve, Washington and his officers met in Stirling’s quarters to discuss a plan to attack the Hessian garrison at Trenton, New Jersey, the next night.

Stirling moved his tiny brigade to McKonkey’s Ferry on the Pennsylvania side of the river, where they crossed into New Jersey. By 4 am, the crossing was complete and Washington’s 2,500-man force marched through snow, sleet, and bitter cold toward Trenton. At 7:45 am, one hour after daylight, Stirling’s brigade formed eagerly and advanced into Trenton, driving the Hessians before them. Forty-five minutes after the attack began, the Hessians surrendered. At the cost of only four wounded, the Americans captured 900 mercenary troops, killed 21, and wounded 90. Once again, Stirling had participated effectively and decisively. The victory was doubly satisfying to Stirling—many of the prisoners were the same Hessians who had captured him in August on Long Island.

After Trenton, Washington pulled his army back across the Delaware. Shortly afterward, Stirling was confined to bed with an attack of gout. He was recovering at his Basking Ridge estate when, on February 19, 1777, he was promoted to the rank of major general in the Continental Army. Thanking Congress for his promotion, Stirling promised, “I shall not omit any occasion of showing myself worthy of the confidence they repose in me.”

Bravery at the Battle of Brandywine

That spring, Stirling joined four other divisional commanders—Sullivan, Nathaniel Greene, Adam Stephen, and Benjamin Lincoln—to oppose Howe’s next move. On August 21, word came that 16,000 British troops were advancing on Philadelphia. Washington quickly marched back into the state, and the two armies collided at Brandywine Creek, south of Philadelphia. Stirling’s division was placed in support on the right flank. That afternoon, Washington ordered his division to help stop the British advance. Moving without delay, Stirling took up position on the high ground south of Birmingham Meeting House and threw up breastworks.

British General Lord Charles Cornwallis attacked before Stirling’s preparations were complete, and Stirling’s 3,000-man division took the full brunt of the British attack. His division checked Cornwallis’s advance for an hour and 40 minutes, with Stirling “acting his familiar role of stubborn and slowly yielding defense.” As Stirling’s line buckled, Washington appeared with Greene’s division and covered the retreat. By holding his position, one observer wrote, Stirling “had proved once more his ability and courage as a battle leader.”

Marching and countermarching across Pennsylvania, the patriots looked for a chance to strike back. Their opportunity came at dawn on October 4, 1777, when Washington’s 11,000 men attacked Howe’s 9,000 troops at Germantown. While Sullivan’s and Greene’s divisions attacked in a thick fog, Stirling’s division remained in reserve. Eventually, Washington ordered Stirling to support Sullivan’s advance. Moving forward, his division was delayed for half an hour by intense fire from British troops sheltering in the stone Chew House before Washington advised him to bypass it.

British reinforcements soon routed Sullivan and Greene. Deploying Colonel William Maxwell’s brigade as a rear guard, Stirling once more covered a patriot retreat to Pennypacker’s Mill. After Germantown, Stirling reported proudly, the British knew that “we can drive them before us for several miles altogether, and that we know how to retire in good order & defy them to follow us.”

Foiling the Plot to Depose Washington

In late October 1777, suffering another attack of gout, Stirling took sick leave in Reading, Pennsylvania. While there, he uncovered a plot by Brig. Gen. Thomas Conway to replace Washington as commander of the Continental Army with General Horatio Gates. Viewing Washington as “indispensable to the cause of independence,” Stirling reported the plot to his commanding general. “Such wicked duplicity of conduct I shall always think it my duty to detect,” he told Washington. The plot was foiled. Stirling rejoined Washington’s army at Valley Forge in late November and endured with his division the short supplies and demoralization throughout the harsh winter of 1777-1778.

A Fourteen Cannon Salute

On June 18, 1778, news reached Valley Forge that a British army led by Maj. Gen. Sir Henry Clinton had left Philadelphia for New York. Washington immediately set off in pursuit, marching his 12,000-man army into New Jersey with Stirling leading the fifth division. On June 27, Washington ordered Charles Lee, recently returned after 15 months in a British prison, to attack Clinton’s rear guard at Monmouth Court House. Lee’s attack failed, and Washington ordered Stirling to place his division on the American left. As his men moved up, they were attacked by the British 42nd (Black Watch) Regiment. Stirling held his ground for two hours, riding along the lines encouraging his men and preventing the British infantry from striking the rest of the American line. Washington’s aide, Alexander Hamilton, praised Stirling for rendering “very essential service in that battle.” Clinton withdrew to New York that night, leaving Washington’s army in possession of the field.

Sporadic fighting continued in New Jersey for the rest of 1778 and into 1779. Early in 1780, Stirling led an unsuccessful raid on Staten Island and later assisted Greene’s attack on Springfield, New Jersey. Just before the Virginia campaign, Washington put Stirling in command of the Northern Department, with his headquarters in Albany. Stirling was at Saratoga in October 1781 when he received the glorious news of Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown. He celebrated the news by firing 14 cannons, one for each of the 13 colonies and “our friends in Vermont,” which was still unincorporated.

Mourning for 30 Days

Stirling remained in active command through 1783, but his attacks of gout got worse. On November 22, after a particularly severe attack, he wrote Washington, “Thank God I am recovering, tho’ it is but slowly.” On January 9, 1783, Stirling fell into a stupor. Two weeks later he died at the age of 57. He was buried with full military honors in the Dutch Cemetery at Albany. At the news of Stirling’s death, Washington ordered the army into mourning for 30 days. “The remarkable bravery, intelligence and promptitude of his lordship in performing his duty as an officer have endeared him to the whole army,” Washington wrote to Congress, “and make his loss more sincerely regretted.” It was high praise, indeed, from the typically reticent commander.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments