By Peter Suciu

Aprevalent image of the Japanese NCO or Officer in World War II is that of rushing the Allied lines with his “samurai” sword drawn, swinging in the air. This owes more to Hollywood imagination and contemporary military propaganda than fact. Still, it is hard to think of the World War II Japanese army officer without the much-recognized sword, an image associated as much with the Pacific Theater as the Japanese “Rising Sun” flag.

Ironically, much about Japanese military swords of the era has been misunderstood. The most common misapprehension is that the Japanese armed forces carried and used “samurai swords.” Although the Regulation 1934 (& 1938) pattern army blades were designed to reflect the traditionalist and nationalistic ideology of Japanese culture of the early 1930s, these swords were not produced in the same manner or even to the same degree of standards as blades of the Shogun eras (12th to the 19th centuries).

These are, however, the most familiar variety of Japanese military swords and are today referred to by the name shin-gunt (meaning new military sword), while the proper designation is “Type 94 (1934) pattern Army Officers sword.” This new model was believed to have been authorized in February of 1934 and was based on the traditional slung sword from the Kamakura period (1185-1332). And while the kinds of master swordmakers who crafted the blades of the earlier eras did not play as great a role in the swords’ production, many of the WWII-era swords are of very high quality—especially those manufactured before the beginning of the war.

Additionally, among the Japanese infantry equipment of the period, the soldier’s sword was one of the few items of especially high quality, in many ways calling up that image of the Japanese soldier as a samurai warrior. While their rifles, machine guns, and other small arms were generally regarded as inferior to those of their American and European counterparts, the Japanese sword was a highly respected weapon—even one that was particularly feared by those who worried that they might be on the receiving end.

The European and American Influence

Japan’s status as the land of shogun and samurai lasted for many centuries, which is one reason for the erroneous beliefs that the bladed weapons used during the modern era were in fact those of the classical warriors.

Until the arrival of Admiral Perry and the U.S. fleet into Tokyo Bay in 1853, Japan had essentially been an isolationist society, ruled by feuding clans of samurai warriors. In a few short years the country underwent a vast societal change that led to the Meiji Restoration of the Emperor to the throne in 1868 and the modernization of the Japanese nation. The ruling Tokugawa-clan shoguns were overthrown and centuries-old feudal customs were abolished. Soon foreign military and industrial advisers arrived to help Japan take a place in the modern world.

This led to the decline of the once noble and powerful samurai class—evidenced in 1871 when the wearing of swords was made optional for samurai, and more dramatically in 1876 when the wearing of swords was forbidden. The era of the samurai ended after the failed rebellion by a former samurai, General Saig Takamori, in 1877.

Even before this final sunset of the samurai, the Japanese were beginning to use equipment of a Western influence. Beginning in 1867 French instructors were imported to aid in the creation of the modern Japanese Army, and the influence was retained for decades in the appearance of the French-styled full-dress uniforms. After the defeat of the French Army in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1872), German instructors were brought in until they were, in turn, recalled in 1894.

The standard officer and NCO swords of this period were therefore virtually indistinguishable from their European counterparts, and were mostly French- or American-inspired. The first apparent drawback of these blades, many of which were mass-produced, was that they were overly flexible and weak. Therefore they were not up to the rigors of the time-honored kend (“way of the sword”) training by officers. Thus, around 1900 the swords underwent a major revision and traditional manufacturing methods were reintroduced.

As a result many of the Japanese military swords of the late 1800s and early 1900s are a mix of mass-produced and traditionally manufactured blades, with even some ancestral blades being adopted for the newer styled swords. The most common types of army swords from the 1800s are of the 1871, 1873, and 1877 pattern varieties. Of these the 1877 pattern sword was the most utilitarian, non-Japanese in appearance, and among the most mass-produced. Numerous variations of these swords were issued to cavalry troopers, and these also included mass-produced blades and Western-style assembly with D-grips.

A further variation known as the kyu-gunt, or proto-military sword, first appeared in 1874 and is noted for its more curved blade and double-handed hilts. Most surviving examples date to the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). Officer swords featured gilt-finished brass hilts while noncommissioned officers carried a similar sword with plain brass mounts.

Additionally, until 1872 there were no regulation naval swords and officers usually carried a traditional katana—the large sword usually referred to as a “samurai” sword—tucked into their leather service belt. The first true Imperial Japanese naval sword was a copy of the British naval saber of 1846. Swords were introduced for officers and NCOs of marines and gunners, with officers and flag officers boasting more elaborate versions including gilded brass mounts. A 1914 naval kyu-gunt introduced with a black leather, lacquered black sam or brown shagreen, was reportedly carried as a matter of preference by senior officers during World War II.

The Shin-Gunt and the Return of Traditional Japanese Swords

The Japanese were particularly influenced by the military institutions of Europe and distilled much of the best of both the samurai and the European fighting traditions. Consequently they were able to develop a fighting force that could compete with those Great Powers. Once the island nation emerged from its international isolation, Japan even began to imitate Europe’s imperialism as well as its militarism. Japan successfully defeated China and Russia in the first Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War and began its bid for a colonial empire on the Asian mainland in Korea, followed by an invasion of Manchuria in 1931.

The strong nationalist feelings were reflected in the introduction of a new sword in 1934 to replace the kyu-gunt with a more traditional and truly Japanese-style sword. “While European-like swords dominated before WWII, the adoption of shin-gunt style swords during WWII was due both to Japanese nationalism and the hopes of elevating the Japanese soldier to ‘samurai’ stature within the culture,” explains Robert Grasso, owner of Kyoto Antiques. “In fact, many old family blades, some several centuries old, were remounted for use during the war.”

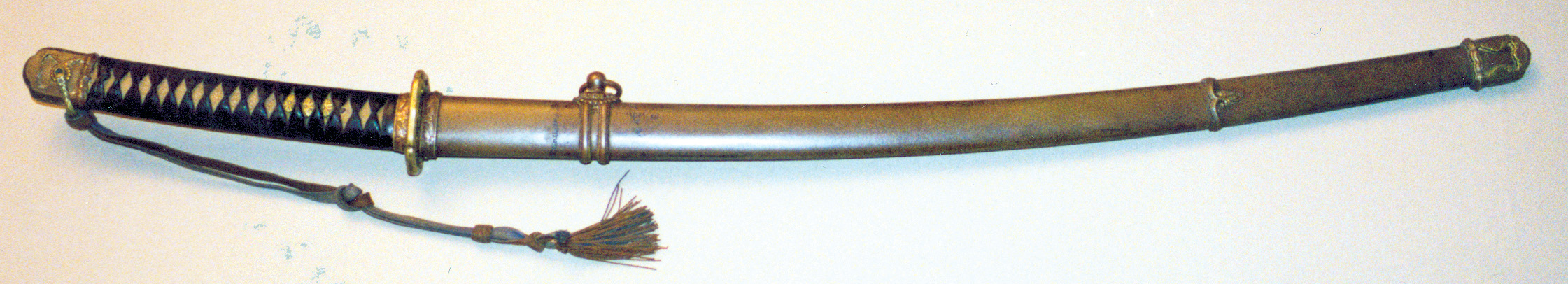

Based on the slung sword, this Type 94 pattern was the most common of all Japanese military swords carried in World War II. Captured ones were erroneously called “samurai swords” by the GIs and others who brought them back home as war trophies. The hilt usually consists of a brownish wrap that is bound over white sam (rayskin) on a wooden base. Fittings are a brass pommel and collars decorated with sakura(cherry blossoms). The hilt can be dismantled and removed from the blade by taking out a bamboo peg that passes through the tang. The hand guard is cast brass in a shape the Japanese call aoi, and is decorated with four raised sakura on each side. The guard may be solid or pierced, possibly depending on rank, which is further indicated by the tassel coloring. This tassel is tied around a brass or copper loop fixed to the end of the hilt.

The swords’ scabbards are typically steel or an alloy and have wood liners. They are almost always painted green, brown, or khaki. Some have appeared in black, which was probably only used from 1943 onward. There are examples with brown leather covers stitched over wooden liners, termed “field scabbards.”

The blades of these Type 94 swords are a mix of machine-made and modern hand-forged, plus a fair number of ancestral swords that have been “militarized” with the proper fittings. As a result there are numerous variations, including those that are a mix of part-military/part-civilian swords, and even those that are a mix of navy and army parts.

A late war officers’ pattern shin-gunt was introduced toward the end of 1944 to conserve brass—an essential war material—and the hilt and scabbard mounts are made of blackened iron. Furthermore, civilian wakizashi (mid-length swords) and katanas dating from earlier than the Meiji period were adapted for military use, especially toward the end of WWII.

Other late war swords are often found with hilts and scabbards entirely covered, and in some cases constructed of leather. Swords were even made in occupied territories when regular supplies from the home islands ceased. These are generally of poor quality and often were made from scrap steel and had little combat effectiveness. Off-duty soldiers or non-Japanese conscripts from Manchuria, Korea, or Formosa—as well as those who desired to own a sword but were forbidden to wear one by rank—may have made and carried them.

A totally mass-produced variation of the officers’ shin-gunt, possibly manufactured before the war in Germany or England, was issued to NCOs as a regulation requirement. These were first introduced in 1934 and feature a cast brass or aluminum hilt that is a copy of the officers’ pattern. The hilt is highly detailed and is painted to represent the color of the binding. The mass-produced blade is fullered (slightly grooved) on both sides and should feature a stamped Arabic assembly number that would correspond to the stamped number on the throat of the steel scabbard. This scabbard would usually be painted green or khaki.

A new naval sword was also introduced in the 1930s to conform to the army’s new sword, and this was based on the traditional tachi (slung sword). The naval kai-gunt consisted of a mix of mass-produced, hand-forged, and ancestral blades. The similarly produced scabbard was usually blue-black or plain black lacquer and no rank distinction is noted—even with the tassel, which was always plain brown.

The majority of Japanese military swords were brought back to the United States by occupying troops after the Japanese surrender on September 2, 1945. Officers and NCOs carried more than a million swords during the war and it was not uncommon for an officer to own two or more swords. After the war Lord Mountbatten, commander of the British forces, demanded that all Japanese surrendering officers hand over their swords at properly constituted ceremonies. It was necessary for senior officers to present their swords to the British or Commonwealth officer presiding, while junior officers and NCOs laid theirs on the ground. American forces under General MacArthur implemented similar procedures, and it was forbidden for the Japanese to possess military or even old civilian swords—most of which were confiscated for distribution or destruction.

Collecting Japanese Military Swords

Following the end of the war, Japanese military swords, again often referred to as “samurai swords,” became an area of interest for collectors. As a result of the sheer number of swords that were destroyed, the collectors’ market has often seen demand outstrip supply. Because of the high cost and rarity of ancestral swords, collectors are turning to those produced during the modern era.

“The market presently, as well as for the past two years, has been very lively,” explains Grasso. “In fact, the WWII Japanese sword market continues to climb and shows no signs of abating. Many collectors, both novice and advanced, do not have the high four- to five-figure cash sums typically required to acquire quality antique swords. Thus, the WWII era swords offer a viable collection alternative where significant appreciation can also be realized.”

The number of variations that turned up during the war has made it possible for quick-buck artists to sell reproductions as originals. Highly detailed NCO and even a few officer swords have appeared in recent years that are believed to have originated in India or Pakistan. These swords are usually correct in nearly every detail, but often have unsharpened or filed blades. Otherwise, the creators have gone to great lengths to simulate wear and tear.

In addition, the recent influx of “samurai” swords from Spain has flooded the market and made it hard for the novice to find authentic merchandise. Although ersatz swords would probably not fool anyone, more and more supposedly “vintage” swords are also beginning to turn up. “The best advice is to become well educated in the area in which you wish to collect,” says Grasso. “Many excellent references are available that deal with both antique and WWII era swords. The work by Fuller and Gregory on Japanese swords of WWII is excellent. Also, sword clubs offer sound advice to both novices and experts. Finally, most dealers are more than willing to share their knowledge with collectors, both from the sales perspective and also to pontificate about their prowess with respect to Japanese swords.”

Almost ironic is the fact that the first “fakes” were actually produced during the war by enterprising Australian troops who made high-priced “samurai swords” for souvenir-hungry American GIs. These, along with many of the modern reproductions, feature spurious tang signatures and pattern fittings that never existed. Such swords are often misrepresented as the low-quality “emergency” or homemade swords, so buyers should be especially cautious when coming across them for sale.

Before purchasing any high-priced military collectable the best advice is to do some research and conduct the transaction with a reputable dealer. And should you already be fortunate enough to have one in your collection or to obtain a sword, consult a reputable dealer before cleaning or attempting to disassemble it. Blades should never be greased, touched by a hand, or cleaned with abrasive materials. Rust on the tang (under the hilt) is actually meant to be there and can help determine a blade’s age.

The Japanese military swords represent an era of great triumphs and horrors for those from both sides of World War II. As with the true swords of the samurai warriors, these well-crafted blades (even those that were mass-produced) invoked feelings of honor and near invincibility to their owners, and brought back the old spirit of the honorable and mighty warriors who carried them into battle.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments