By Blaine Taylor

After Imperial Germany lost the Great War (1914-1918), the Treaty of Versailles punished her severely in terms of ruinous restitution payments to the victors, economic sanctions, the loss of territory and colonies, the forced abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II, and the heavy restrictions imposed on her armed forces. Virtually all historians agree that it was these onerous conditions that led to the rise of Adolf Hitler and the start of a second world war within a generation.

The victorious World War II Allies also severely punished Germany and her surviving wartime leaders for starting the conflict that ravaged Europe and killed millions. In a move unprecedented in legal history, a series of war-crimes tribunals was established a few months after the end of the war to fix blame on certain individuals who were held responsible for the heinous acts of their government.

The following is a recounting of those tribunals and their outcomes.

Even at the height of World War II, the group of wartime Allies—France, England, Russia, and the United States—had decided that, if the Allies were to emerge victorious again, individual Germans would be held accountable.

At one time or another, both British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet Premier Josef Stalin bandied about the notion of simply shooting 50,000 German officers without trial to prevent yet a third Teutonic war in Europe. U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt demurred, however.

Joking or not, they all agreed that something more had to be done about a captured German leadership corps postwar, from the top to the bottom. By war’s end in May 1945, the International Military Tribunal (IMT) had been established via the London Agreement—a convenient way of bypassing civilian legal niceties.

Selected as the actual site of the IMT events was the largely undamaged Palace of Justice at Nuremberg, Germany—scene of the giant Nazi Party rallies in the 1930s, as well as all of the Third Reich’s prewar-enacted anti-Jewish laws.

Thus, the stage was set for the first—and today the most remembered—of what over the next four years became 13 separate trials, of all levels of miscreant Germans.

The First Trial

The first important proceeding of the IMT was the trial of the 22 major war criminals at Nuremberg, from November 1945 to October 1946. Most of the rest followed in the same Palace of Justice in the courtroom that still exists today.

The IMT set the standards and practices for the trials that followed, first by refusing to accept the accused’s common defense that they were “just following orders from above” as valid.

The four indictments specified: participation in a common plan or conspiracy for crimes against peace; planning, initiating, and waging wars of aggression; war crimes; and crimes against humanity—the latter covering the Holocaust against Jews, gypsies, and others. These fell under a new, invented term—genocide—that still survives.

The first trial ran from November 20, 1945, through the hanging of 10 condemned men on October 16, 1946 (three were acquitted, later dying natural deaths). All pleaded not guilty. Of the accused defendants, three ultimately committed suicide: Labor Leader Dr. Robert Ley before the trial, Reich Marshal Hermann Göring hours before his scheduled execution in 1946; and—amazingly—Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess 41 years later, in 1987, at Berlin’s Spandau Prison.

The indicted Nazi Party Secretary Martin Bormann was tried in absentia and also condemned to death. (His body was found at a construction site in 1972 in Berlin, where he had died in 1945, being “missing” for decades.)

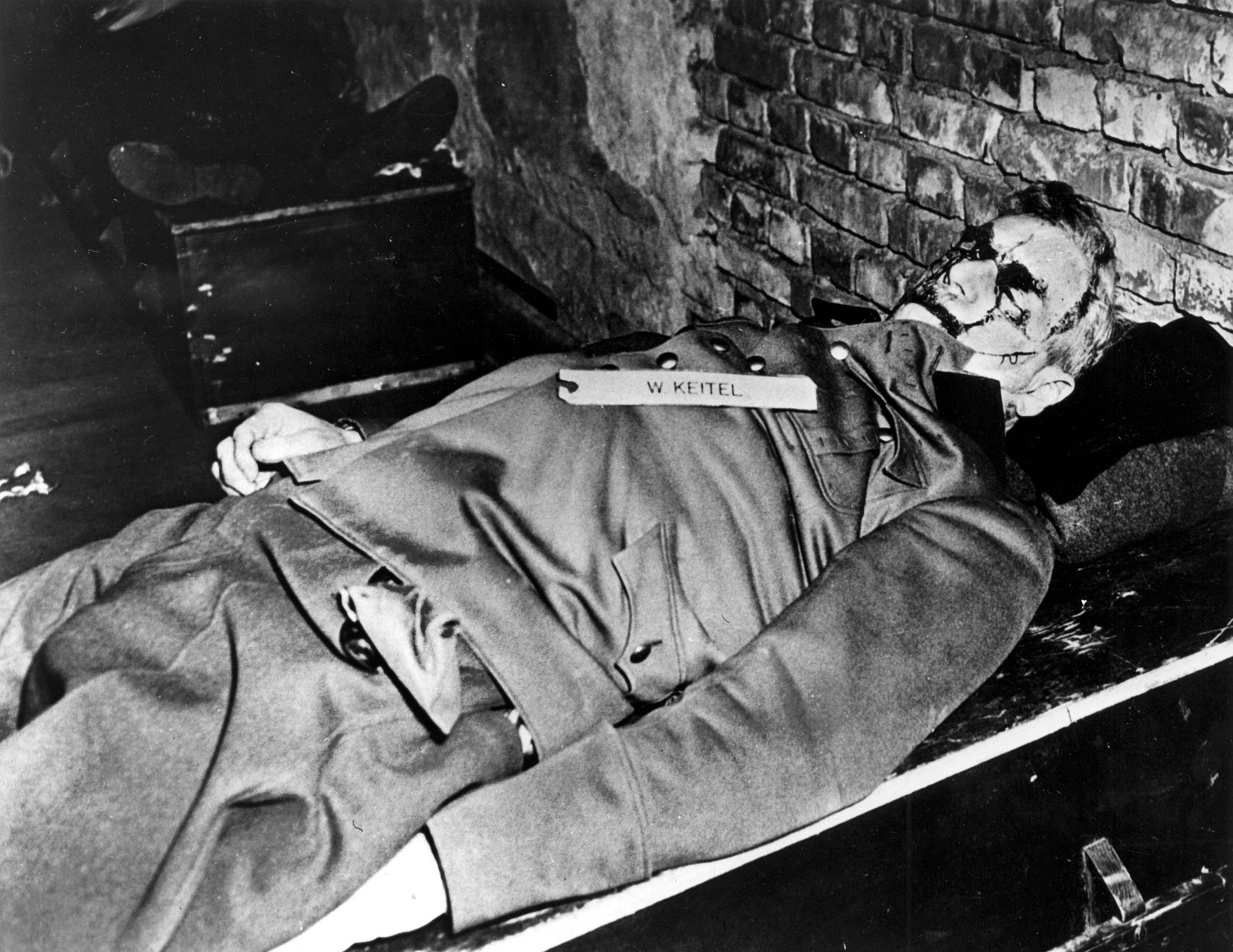

The hanged convicts were: Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop; Army Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel; Col. Gen. Alfred Jodl; SS General Ernst Kaltenbrunner (standing in for the late Heinrich Himmler); Reich Minister of the Interior Dr. Wilhelm Frick; Nazi Governor-General of Occupied Poland, Dr. Hans Frank; Governor-General of Occupied Holland, Dr. Artur Seyss-Inquart; Minister of the Conquered Eastern Territories, Alfred Rosenberg; slave-labor czar Fritz Sauckel; and race-propagandist Julius Streicher.

It is now generally agreed that the official U.S. Army hangman—Sergeant John C. Woods—bungled the hangings, either via incompetence (doubtful) or deliberately, to make the convicted men suffer for their crimes via slow strangulation, as opposed to quickly having their necks broken.

Photographs of the dead show some with bloodied faces from having struck the edge of the open trap door on their plunge downward. The cocky hangman Woods boasted afterwards, “I hanged those 10 Nazis!” Sauckel and Ribbentrop choked to death over 14 minutes each, and Keitel double that, at 28—the most painful of them all.

Of the other six men imprisoned at Spandau, Foreign Minister Baron Konstantin von Neurath was released in 1954 after a heart attack, dying in 1956; Grand Admiral Dr. Erich Raeder was released due to ill health in 1955, dying five years later; and Economics Minister Walther Funk went home ill in 1957, dying that same year.

Sentenced to 10 years was Grand Admiral and Reich President Karl Dönitz, who served his full term, was released in 1956, and died in 1980. Dying in 1981 was Minister of Armaments Dr. Albert Speer, having served his full 20-year term, as had Hitler Youth leader Baldur von Schirach; both were let out in 1966, with the latter dying in 1974. The seventh man—Hess—served from 1947-87, plus an earlier four years as a British POW, 1941-45.

The November 1937 Hossbach Conference Memo was introduced as evidence showing that Hitler and his top warlords, plus Neurath, began plotting World War II from that period and originally slated it to start in 1943, moving it up to September 1939 with the invasion of Poland.

Several secondary and middle-level Germans testified for the prosecution against the defendants, the most notable being then-Russian POW German Army Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus of the Stalingrad debacle; he had drafted the invasion plans to conquer the U.S.S.R. Paulus became an inspector for the East German Police, strangely, in 1957.

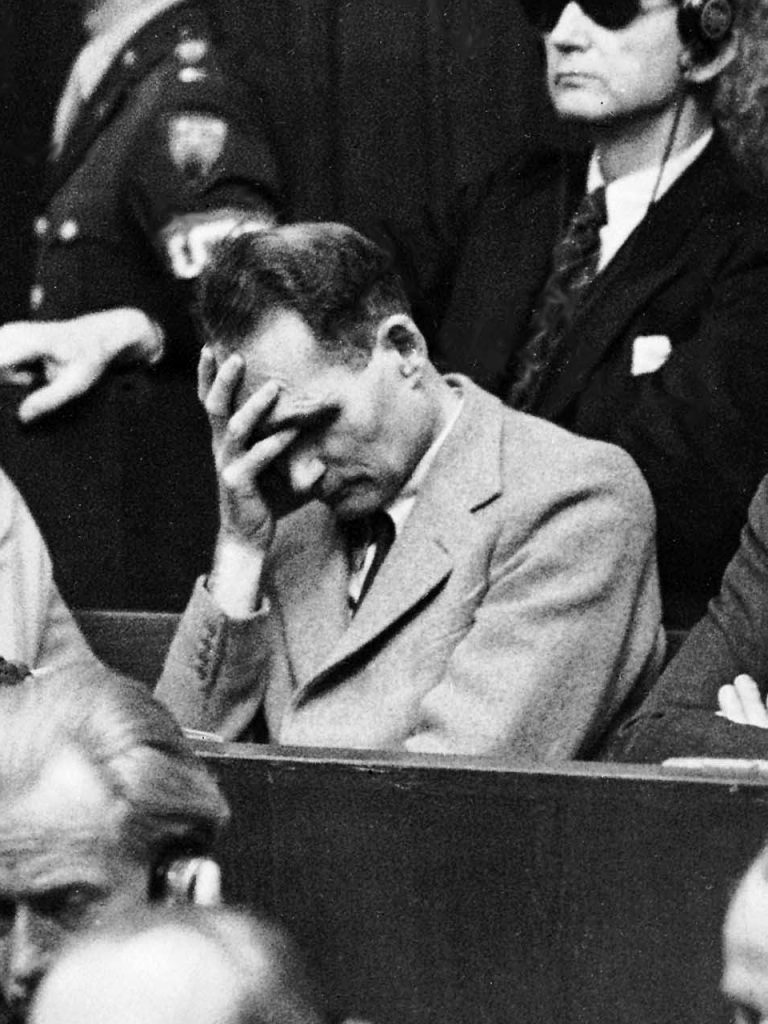

Essentially, the main courtroom fight was a set-up “battle” between Göring’s “Hitler-was-right” testimony on the one hand, and the testimony of so-called “Good Nazi” Speer, with his pro-Allied mantra of “Hitler-was-the-mad-war-criminal,” on the other. Between those two poles stood everything else. Göring knew he would hang (but didn’t) so stood his ground, while Speer cut a tacit deal with the Americans in advance, thus knowing he wouldn’t.

Two others who recanted their Nazi past were von Schirach—who wasn’t hanged—and Seyss-Inquart, who was. Recanter Hans Frank was also hanged.

Of the military defendants, both soldiers were hanged, while neither admiral was, mainly due to the written testimonials of American admirals and others who admitted they would have done the same things as the accused naval officers during wartime.

Of the diplomats, the arrogant Ribbentrop was the first on the gallows, while gentleman von Neurath was spared. As Fritzsche was only present as the stand-in for the late Dr. Goebbels, he was freed, as were the pre-Nazi Chancellor Franz von Papen and the cranky ex-Reichsbank president Dr. Hjalmar Schacht—the latter partially because he was himself a Nazi concentration camp inmate (at Flossenbürg) at war’s end.

The greatest prosecution deception attempted during the 13 trials occurred when the Soviets tried unsuccessfully to pass off their own 1940 Katyn Massacre of Polish Army officer-corps POWs (admitted as such 50 years later) as a Nazi crime, when all present knew the reverse to be true; hence, the matter was thus quickly dropped.

Another controversy concerned the overall debate time before the sentencing of all the accused; the Allied judges took a mere two days, while most ordinary American murder trials today take far longer than that.

Chief prosecutor for the U.S., Supreme Court Associate Justice Robet H. Jackson wrote “shamefacedly” that the Allies themselves “have done—or are doing—some of the very things we are prosecuting the Germans for! The French are so violating the Geneva Convention in the treatment of POWs that our command is taking back prisoners sent to them! We are prosecuting plunder, and our Allies are practicing it!

“We say aggressive war is a crime, and one of our Allies [the U.S.S.R.] asserts sovereignty over the Baltic States, based on no title except conquest!” He was right.

Liberal Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas added, “I thought at the time—and still think—that the Nuremberg trials were unprincipled. Law was created ex post facto [after the fact of the crimes] to suit the passion and clamor of the time.”

IMT Chief Russian Prosecutor Red Army Lt. Gen. Roman A. Rudenko became the postwar commandant of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, where ex-Nazis were held by the Soviets and where—after the fall of communist East Germany—12,500 bodies of elderly German men and women, and also children, were discovered.

Finally, Soviet Judge Red Army Maj. Gen. Iona Nikitchenko had earlier taken part in Stalin’s notorious political Great Purges of 1936-38. Indeed, in 1936 alone, over 900 were executed daily, while during the last two years an estimated 681,692 were shot.

Many Germans complained about “victors’ justice”—that both sides bombed cities, killed civilians, and also relocated millions of people all across Europe during the war—the Allies more so and well into 1949—but only the losing side was held to account. America’s dropping of two atomic bombs is still considered a “war crime” by some.

Overall, the 13 trials covered an estimated 3,889 charges, of which fully 3,400 were dropped. Still, 489 cases went to trial, with 1,672 defendants. Of these, 1,416 were found guilty; fewer than 200 were actually executed, with a further 279 sentenced to life imprisonment. Of the latter, by the mid-1950s almost all of them had been released.

One reason for these low numbers was, as the Soviet Communists charged of their former wartime Western Allies, the 1955 establishment of the new West German Federal Army—the Bundeswehr—as a new, Cold War element of NATO. Indeed, one of the late Marshal Erwin Rommel’s top wartime aides—General Hans Speidel—served later as a NATO commander, while many high-ranking Luftwaffe aces of World War II commanded the new West German Air Force.

“Subsidiary and related trials” after the 13 major proceedings were held by other courts against concentration- and extermination-camp personnel who ran or served at Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen, Belzec, Buchenwald (where the infamous Ilse Koch was tried), Chelmno, Dachau, Majdanek, Mauthausen-Gusen, Ravensbrück, Sobibor, and Treblinka.

In addition, in May 1960, former Austrian Nazi SS Colonel Adolf Eichmann—who had escaped to Dictator/General Juan Peron’s Argentina, where he lived under an assumed name with his wartime family—was kidnapped outside of Buenos Aires by Israeli Mossad agents. Flown to Israel, Eichmann was tried, convicted, and hanged in 1962 for facilitating the Holocaust in Hungary and elsewhere.

After the main IMT trial of the 22 top Nazi leaders, the following 12 trials fell into the separate legal category of “United States versus….”

The Doctors’ Trial

The first such—The Doctors’ Trial—was held before a U.S. Army military court, as were all the succeeding trials. Its indictment was filed on October 25, 1946, against 23 defendants—20 of them being professionally trained and graduated medical doctors from prestigious medical schools, while three were non-M.D. high Nazi officials.

As with Martin Bormann, Dr. Josef Mengele (the “Angel of Death”) escaped justice altogether, drowning in Brazil during a self-imposed exile in South America. His family supported him financially from its farm-machinery company in Bavaria until his death.

Of the 23 indicted, seven were acquitted and seven were condemned to death by hanging, the rest being imprisoned for from 10 years to life. Another M.D. who escaped justice was Dr. Leonardo Conti, who hanged himself in his Nuremberg cell in October 1945 before his trial.

The major figure in the dock of the accused was SS General Dr. Karl Brandt, Hitler’s personal travel physician, Reich Commissioner of Sanitation and Health, and co-administrator of the 1939-41 Final Solution’s predecessor program, Aktion T4.

Under the aborted Aktion T4, Karl Brandt had caused the aged, insane, incurably ill, and deformed to be medically murdered via gas, lethal injections, etc., in their nursing homes, hospitals, and asylums, in what was officially but quietly called “The Euthanasia Program.” Hitler shut it down due to public pressure from the Third Reich’s vocal Catholic pulpits. As Hitler told religion-hating Bormann, “The problem of the churches will have to wait until after the war,” as he needed Catholic soldiers to first win it.

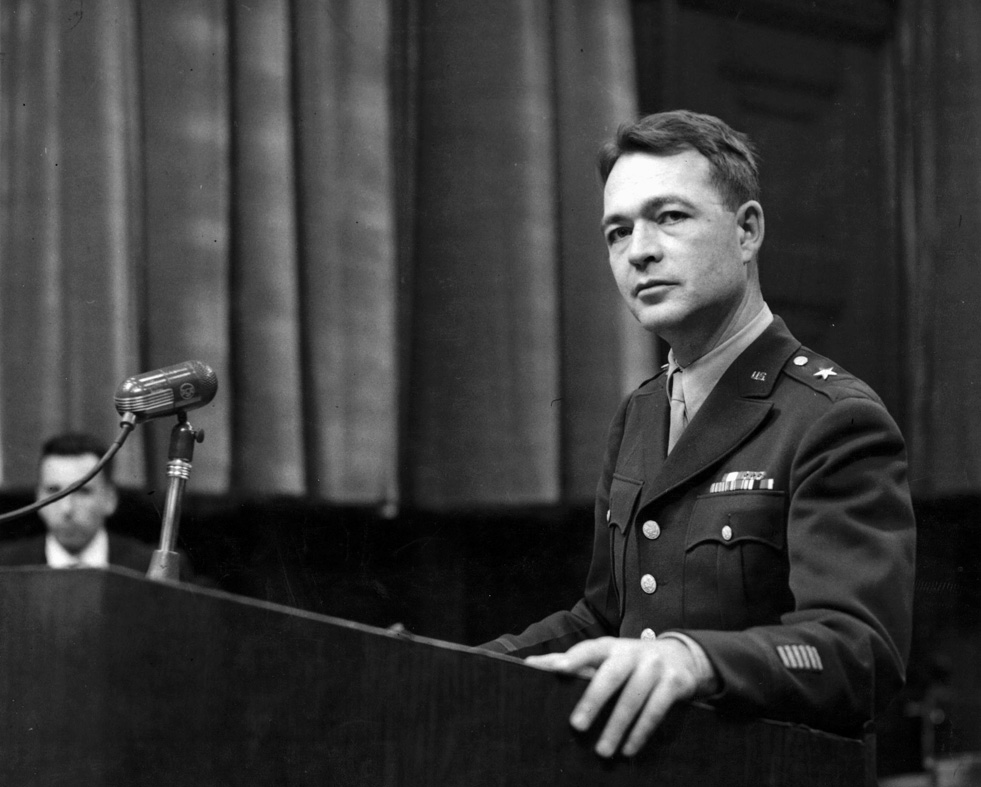

Brig. Gen. Telford Taylor’s main medical charges were for illegal and inhuman experiments on unwilling victims—both POWs and occupied-country civilian nationals—in the course of which they were tortured and often died terribly.

The Doctors’ Trial lasted 140 days, with 85 witnesses testifying, and nearly 1,500 documents introduced as evidence. The heinous medical “experiments” on live subjects encompassed many tests: high-altitude/oxygen deprivation; freezing in ice water; prolonged exposure to sea water; malaria; typhus; mustard gas; sulfanilamide; bone, muscle, and nerve regeneration and bone transplantation; epidemic jaundice; sterilization; spotted fever; tuberculosis; unspeakable experiments on pregnant women and young twins; and incendiary-bomb experiments.

The Judges’ Trial

The third—the Judges’ Trial—included 16 high German jurists and attorneys, nine of whom had been top officials of the Reich Ministry of Justice, with others serving as judges and prosecutors of Nazi Special and People’s Courts.

Among other charges presented on January 4, 1947, the Nazi judges were accused of both implementing and advancing the Party’s racial purity program via eugenic and racial laws. Their crimes included running a judicial/penal process that resulted in mass murder, torture, private property plunder, and slave labor, as well as membership in two organizations officially declared criminal by the IMT: the Nazi Party itself and its SS/Security Service Leadership Corps (but not the SA Stormtroopers).

Of the 16 defendants, 10 were found guilty, four sentenced to life, and six to lesser prison terms; four were acquitted of all charges. Four top Nazi jurists had already died before the trial started.

The Pohl Trial

The fourth, the Pohl Trial, brought to justice main defendant SS General Oswald Pohl and 17 others of the SS Main Economic & Administrative Office, or SS-WVHA. Their main crime was the actual administration of the murder apparatus used to accomplish what the Nazis called “The Final Solution of the Jewish Question”—their physical extermination—in a chain of death camps across German-occupied Europe during 1942-1945, mainly in Poland.

In addition, the 18 high SS officers ran the concentration labor camps from 1933 on and recruited the Waffen/Armed SS combat divisions, as well as the Death’s Head units that staffed all the camps.

Convicted, Pohl and three others were hanged, three were acquitted, and the remaining convicted war criminals sentenced to terms of 10 years to life; two had their death sentences changed to life. Another who had earlier commanded all the camps committed suicide two days before the German surrender of May 8, 1945. Pohl was hanged on June 7, 1951.

The Flick Trial

The fifth tribunal, the Flick Trial, charged its defendants with both using slave labor and plundering, with German industrialist Friedrich Flick and Senior Director Otto Steinbrinck also accused of being members of the “Circle of Friends” of SS Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler, who killed himself while in British custody on May 28, 1945.

The “Circle” encompassed prominent German bankers and heavy industrialists who supported Nazi crimes financially, donating one million marks to Himmler’s “Special Account S.” The indictment on March 18, 1947, said there was participation in the deportation and enslavement of civilians in lands occupied by the Third Reich for usage in both Flick mines and factories, plunder and despoilation of those lands, and also plant seizures.

All pleaded not guilty, but Flick was sentenced to seven years; two received lesser terms, and another trio was acquitted.

The Trial of I.G. Farben

The sixth trial, I.G. Farben, began on May 3, 1947, against the manufacturer of the pesticide Zyklon B that was used in the death camp gas chambers to kill Jews and others deemed racially unfit by Nazi Germany.

All of the accused had served as wartime Farben directors of the IGF overall conglomerate of German chemical firms. Farben also produced synthetic gasoline and rubber from coal, thus lengthening the time Germany could wage war after losing its foreign oil fields to the Red Army, as well as utilizing slave labor and also plundering on a massive scale.

Of the 24 men indicted, 13 were found guilty and sentenced to prison terms up to eight years, and 10 were acquitted; Flick’s chief attorney had his case dropped for medical reasons. Two were released after judgment for time already served.

The Hostages Trial

The seventh trial, Hostages, centered on top German Army commanders in Greece and Yugoslavia, and, to a lesser extent, Albania. The indictment was filed on May 10, 1947—two years after the war’s end.

It charged the accused with mass murder of hundreds of thousands of anti-fascist combat partisans and civilians, hostage taking, and reprisal executions; wanton plundering and destruction of villages, including in Occupied Norway; murder and ill treatment of POWs; naming combatants as partisans to disguise their murder; plus torture and deportation via rail shipment to concentration camps.

All the accused were indicted on all counts, and all pleaded not guilty. Of the 10 actually tried—one committed suicide pretrial, and Army Field Marshal Maximilian von Weichs was not tried due to poor health—two were acquitted, with the remaining eight being sentenced to prison terms of from seven years to life.

The Race and Settlement Trial

The eighth trial, RuSHA, charged 14 SS organizational defendants who had administered the infamous Nazi Race and Settlement Main Office, including leaders of the Commission for the Consolidation of German Nationhood, the Repatriation Office for Ethnic Germans, and the Lebensborn Society. The indictment, presented on July 7, 1947, charged the kidnapping of children as possible Aryans; forcing abortions on women pregnant with non-Aryan or “defective” children; the plundering and deportation of populations from occupied countries to Germany; the subsequent re-population of ethnic Germans to those lands; imprisoning those having interracial sex; and the overall persecution of Jews.

The four Lebensborn defendants were found not guilty on two counts of the indictment, and the Society as a whole was deemed not responsible for kidnappings carried out by others.

Defendant Ulrich Greifelt, condemned to 20 years at Landsberg Prison in Bavaria—where Hitler himself had been jailed by a German court during 1923-24—died there on February 6, 1949, while RuSHA head Richard Hildebrandt was sent to trial in Poland, and was hanged on March 10, 1952.

A trio of defendants was released in 1951, while two sentences that same year were reduced to 15 years, and one to 10. Another convict was released in 1954.

The Death-Squad Trial

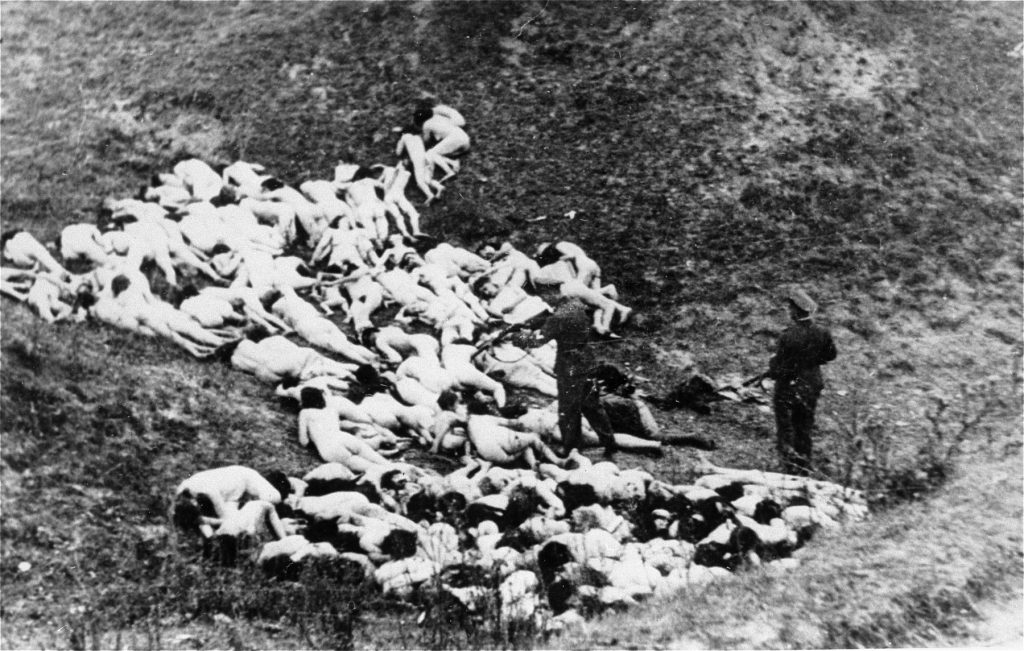

Perhaps the most horrific of all the trials was the ninth—the trial of SS Einsatzgruppen mobile death-squad unit commanders. Operating behind the German front lines in the Occupied East—both in the Baltic Republics and the Soviet Union—these mobile killing units slaughtered more than a million Jews during 1941-1943 alone, as well as “tens of thousands” of alleged “partisans”—a term often used as a cover for Jews—Romani gypsies, disabled people, Red Army Communist Party political commissars, Slavs, homosexuals, and others considered deviant.

The amended indictment was presented on July 29, 1947, with all defendants charged on all counts, and all pleading not guilty. Except for two defendants out of 24, all were found guilty on all counts, with the pair only guilty on count three.

The Einsatzgruppen Trial had as its main defendant suave lawyer and SS General Otto Ohlendorf, who was convicted and hanged at Landsberg on June 7, 1951, as were three other condemned SS war criminals on the same date.

Eight other SS murder-unit commanding officers condemned to hang had their sentences commuted to life imprisonment (and another to 10 years); six were released by 1958, all dying natural deaths as free men. One died after transfer to Belgium, another committed suicide, and one was released for time served; two more received sentences of from 10-20 years but were later released.

When this operation was deemed too costly and not numerically efficient enough, the Final Solution was at last reached in late 1941 into 1942. This consisted of the death camps with gas chambers disguised as water showers that achieved massive daily fatalities.

Ironically, the Einsatzgruppen crimes might have been entirely overlooked but for another significant hire by General Taylor—that of U.S. Army Sergeant Benjamin Ferencz, a Hungarian Jew who was also a graduate of the Harvard Law School.

Ferencz was assigned to head a team of 50 Allied researchers in fallen Berlin to scan 10 million captured Nazi Party official files.

One of Ferencz’s researchers, working at former Gestapo/Secret Police headquarters, “stumbled upon a nearly complete set of … the SS Einsatzgruppen records…. These extermination squads—some 3,000 men—over a two-year period…systematically slaughtered over a million helpless men, women, and children….” (See WWII Quarterly, Fall 2019.)

“I showed the discovery to General Taylor,” Ferencz said, “and urged him to prepare a new trial…. At age 27, I’d yet to try a case…. I offered to handle the prosecutions myself. Taylor smiled—but agreed. I was promoted to chief prosecutor … in the trial against the Einsatzgruppen,” and thus was legal history made.

The Krupp Trial

The tenth trial, Krupp, had as its main defendant the son (Alfried) of the man (Gustav) whom the Americans had really wanted to try in the first trial. It was a rather ironic reversal of the ancient adage of not visiting the sins of the father upon the children.

Ironically, there were no trials at all of aircraft builders like Heinkel, Messerschmitt, Dornier, etc.; of surface and submarine naval warship yard titans like Hamburg’s Blohm+Voss; nor of bombsight optical firms like Siemens; nor of formerly civilian automakers-morphed-into tank, artillery, and field motorized-vehicle builders such as Daimler-Benz, Volkswagen, and BMW. This was because the Allies recognized that all of the above firms would be needed to launch their new Central European ally, West Germany.

Krupp and his directors were convicted of building the arms that allowed the Nazis to wage their aggressive wars of conquest. The Krupp indictment was issued on November 17, 1947. Of the dozen defendants, one was acquitted, the others received prison terms of from three to 12 years, and Alfried was ordered “to sell all his possessions.” The Krupp firm was en toto convicted of using 100,000 slave laborers, of whom an estimated 23,000 were Allied and Red Army POWs.

The firm was convicted, too, of “plunder, devastation, and exploitation of occupied countries; of murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, imprisonment, and torture…” Ten of the Krupp directors were charged on all counts, while a pair faced fewer.

All were convicted on a variety of counts, one was acquitted and, by January 31, 1951, all except one had been already released, their sentences ranging from two years to 12 thus being overturned.

In 1953, Alfried Krupp simply resumed his family firm’s ownership after no buyer for it had been found. The company, which still exists, is now known as ThyssenKrupp. (Ironically, Thyssen company president Fritz Thyssen was an early Hitler supported but ended up in concentration camps for changing his mind about the Nazi leader. He was also tried by a tribunal and let off with a $1,500,000 fine.)

The Ministries Trial

The eleventh trial, Ministries (Wilhelmstrasse), had as its main defendants 21 men, including Ribbentrop’s former Foreign Office permanent State Secretary Ernst von Weizaäcker. (His son Richard was the elected President of the West German Federal Republic for 10 years and of united Germany for four more.)

Some of the defendants were career diplomats who ran all the German regime’s foreign relations, while the rest were bureaucratic civil servants.

Of the overall 21 defendants, a pair was acquitted, while the remaining 19 were found guilty on at least a single count of the indictment, receiving sentences from three to 25 years. None were hanged.

Of the 21, the most prominent were Weizaäcker (five years reduced, and released in 1950); Hitler’s personal economics adviser Wilhelm Keppler (10 years, released in 1951); Ernst Wilhelm Bohle (head of the Nazi Party’s own non-State foreign office, served five years); Edmund Vessenmayer (ruled German-occupied Hungary, 1944-45, 20 reduced to 10, and released in 1951); Reich Chancellery chief Dr. Hans Heinrich Lammers (also with a 1951 release); and a pair of Reich Food and Agriculture czars, Richard Walther Darré (sentenced to seven, freed in 1950) and Herbert Backe, who evaded trial via suicide on April 6, 1947.

Trial of the High Command

The indictment for the twelfth and final proceeding, High Command, was filed by Taylor on November 28, 1947. It focused mainly on the top warriors of Nazi Germany’s armed forces, including just a single naval admiral—Otto Schniewind (acquitted, died 1964)—and a sole Luftwaffe field marshal, Hugo Sperrle, acquitted and dying in 1953 of natural causes.

Sperrle had been the first Condor Legion commander in 1936-1937 in Spain’s Germany-assisted Civil War, being thus responsible for the first mass bombing in aerial warfare of the Basque village of Guernica.

Sperrle also helped conquer France in 1940, and in 1944 commanded the remnants of the Luftwaffe during the Allied Normandy campaign until Hitler fired him.

Of the Army warlords, only two were field marshals, surprisingly: Wilhelm von Leeb (released after trial and died in 1956) and Georg von Küchler; both held top commands in Russia. Küchler was released in 1952 and lived 16 more years.

Of the colonel generals, Johannes Blaskowitz either committed suicide during the trial or was murdered inside the prison on February 5, 1948.

Hermann Hoth was paroled in 1954 and died in 1971. Georg Hans Reinhardt was released in 1952, dying in 1963. Hans von Salmuth was released in 1953, dying in 1962.

General of Infantry Karl von Roques was sentenced to 20 years but died on December 24, 1949. General Hermann Reinecke received life imprisonment for the deaths of 3.3 million Red Army POWs as chief of the High Command’s General Office of the Armed Forces but was released in 1954, dying in 1973.

General Rudolf Lehmann was the High Command/OKW Judge-Advocate General who issued the order that allowed the murder of Soviet civilians as partisans. He also drafted the December 1941 “Night & Fog” decree that seized civilians in the occupied lands without any legal due process.

General Otto Wöhler was convicted for enforcing the Russian invasion’s Operation Barbarossa Jurisdiction Order, deporting civilians for slave labor, and working with the SS Einsatzgruppen murderers. Receiving only eight years, Wöhler was released in 1951 and lived until 1987.

Of the 14 defendants—all of whom plead not guilty—two were acquitted, one died, and the rest received prison terms from three years to life to time served. The guilty had been convicted of violating international treaties and waging aggressive war.

There were no Allied war crimes trials of any kind for the Italian Fascist leaders, except for the simple Communist expedient of shooting them all in April 1945, starting with Benito Mussolini. Most of the Italian marshals, generals, and admirals escaped the Red Partisan firing squads.

There were, of course, the Tokyo Trials (and many others) of the captured Japanese warlords, but that’s another saga altogether.

In truth, there were so many Germans who had committed heinous crimes or profited from the war that 90 percent of the nation’s population would have been brought to justice had the Allies had the time, resources, and will to try everyone. Many millions of perpetrators received little punishment or escaped justice completely—their only sentence being the private guilt they had to carry for their rest of their lives.

Was true justice served? Were the 13 Nuremberg Trials an effective deterrent to wars since? Not at all. On the downside of the ledger, as Göring himself correctly asserted, “The moral is, Don’t lose a war!”

Blaine Taylor’s latest of 23 books is the forthcoming Teutonic Titans: Hindenburg, Ludendorff, and the Kaiser’s Marshals and Generals. He is a former managing editor of the Bulletin of Psychiatry & the Law, 1979-81, as well as of The Maryland State Medical Journal, 1974-81. He has also published the first of a series of four books entitled, The Personal Photograph Albums of Hermann Göring.

Do I catch a whiff of sympathy from the author for the Nazi war criminals? Despite listing at least some of the inhuman atrocities committed by the Nazi regime, this article compares American and Allied prosecution of the war – started by the Nazis, the Italians and the Japanese – as equivalent.

Perhaps the author can give us a better, more humane course that could have been taken to finally overcome the machine-age and vicious savagery perpetrated by the Axis throughout the war.

Blaine Taylor, the author, passed away last year so won’t be responding. Blaine worked many years ago for Time/Life Books, and later, with me at another publishing company. I would say he, like many people, was fascinated by the rise and fall of Hitler’s Third Reich. I don’t believe he had any sympathy for war criminals, Nazi, or other.

Well, God rest his soul. Charitably, he may have gotten too sympathetic to his subjects if he compared our actions in WWII to those of our enemies.

The Nuremberg trials and the other war crimes trials in Germany and Japan were fair, judicially sound, and astonishingly lenient, given the vicious depravity of the crimes committed. Had I been in charge of dealing with the Nazi and Japanese war criminals, the firing squads would have been busy dealing with every single murderer as yet unkilled from that war.

Indeed. We gave these Axis war criminals much more fair and lenient justice than the victorious Axis would have given any Allies they considered to be war criminals. Agree the justice meted out was generally overly lenient and should have been much harsher.