By David Alan Johnson

The first Japanese general officer to suggest abandoning Guadalcanal to the Americans was probably Maj. Gen. Kenryo Sato, the War Ministry’s chief of its Military Affairs Bureau. More important, General Sato was also an adviser to General Hideki Tojo, Japan’s prime minister. At Army headquarters in Tokyo, Sato advised Tojo not to send any more men and supplies to the island and that he should “give up the idea of retaking Guadalcanal.”

“Do you mean withdrawal?” Tojo wanted to know.

“We have no choice,” Sato replied. “Even now it may be too late. If we go on like this, we have no chance of winning the war.”

Tojo listened to what Sato had to say and recognized the truth of his argument. Japan had already overextended itself in men and equipment for the Guadalcanal campaign. But many senior officers, as well as Emperor Hirohito himself, were not yet ready to give up. During a special meeting of his cabinet on December 5, 1942, Tojo agreed to send 95,000 tons of supplies to the starving troops on Guadalcanal. This was in addition to 290,000 tons that had already been agreed upon. The subject of abandoning Guadalcanal had been raised, however. It would come up again in the very near future.

The exchange between General Sato and Tojo had also taken place in early December 1942, when the Japanese War Ministry and the Army General Staff were already beginning to talk about withdrawing from Guadalcanal. It was a subject that would have been unthinkable even a month earlier, but after nearly four months of brutal fighting, the realities of the costly and frustrating campaign were beginning to sink in.

The Three Attempts of the Tokyo Express

Japanese forces had been trying to retake Guadalcanal and its airfield, named Henderson Field by the Americans, since August 7, 1942, when U.S. Marines first landed on the island. During the next several months, Japanese and American forces fought six major naval battles in the waters around Guadalcanal and engaged in almost continual ground fighting. Both sides endured serious losses in men, ships, aircraft, and resources. The major difference was that the Americans could afford the losses; the Japanese could not.

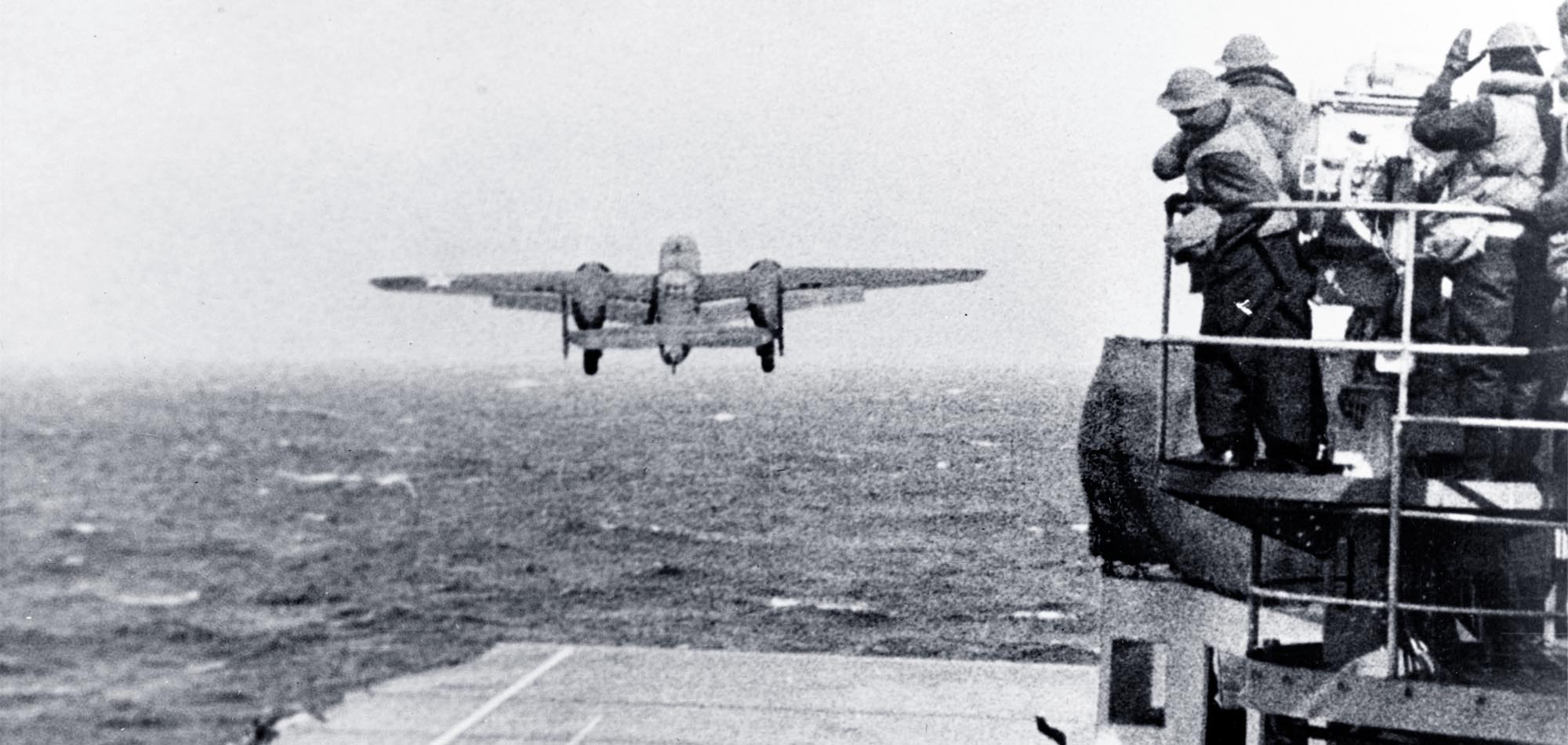

The Japanese Army General Staff had never intended to give up even though all its efforts had ended in failure and insisted that the troops on Guadalcanal be resupplied. The Navy came up with an improvised method of delivering food, ammunition, and medical supplies, a system that would employ the use of metal drums. These would be partially filled with whatever they were carrying, leaving enough air inside to keep the drum afloat. They were then sealed and strung together necklace fashion and loaded aboard a destroyer. Destroyers had been used to deliver troops and supplies to Guadalcanal for months. They had made their runs down the channel separating islands of the Solomons archipelago, which had come to be known as the Slot, with such regularity that they had been nicknamed the Tokyo Express. The only new twist was the use of floating drums.

Several destroyers would be dispatched to Guadalcanal to unload their cargoes. The strings of drums were to be unloaded over the side and towed as close to shore as practical. When the destroyer came as close to the beach as possible, the drums were released. While the destroyer headed back to sea, swimmers from shore would pick up one end of the string and pull the drums toward the beach.

The plan looked good enough on paper. Rear Admiral Tamotsu Tanaka was given the job of seeing if it would work. On the night of November 29, Admiral Tanaka’s flagship, the destroyer Naganami, led a column of seven other destroyers toward Guadalcanal. Six of the destroyers were loaded with the supply drums. At about 11 pm, the column steamed past Savo Island and turned southeast toward Tassafaronga Point. The six supply destroyers were preparing to cast off their drums when American warships— actually five cruisers and six destroyers—were sighted. Tanaka ordered the supply destroyers to stop unloading, rejoin the column, and prepare for battle.

In the engagement that followed, sometimes referred to as the Battle of Tassafaronga, the Americans had the advantage of radar. But Admiral Tanaka had the Long Lance torpedo, which turned out to be even more of an advantage. Radar-directed gunfire from the American cruisers smothered the destroyer Takanami with a wall of water splashes and soon turned the destroyer into a flaming wreck. The gun flashes provided a very nice aiming point for Tanaka’s torpedomen, who proceeded to launch their Long Lances at the bursts of light.

Aboard the cruiser USS Minneapolis, the men on deck cheered as they watched Takanami absorb close to a dozen hits and burst into flame, but their cheering stopped abruptly when two torpedoes hit their own ship. In short order, the cruisers New Orleans, Pensacola, and Northampton were also jarred by torpedo hits. Northampton actually took two torpedoes and sank stern first. After launching his torpedoes, Admiral Tanaka reversed course and headed back to base in the Shortland Islands.

Tanaka had certainly gotten the better of the larger American force. In about half an hour and without benefit of radar, his destroyers had sunk one cruiser and badly damaged three others at the cost of just one of his destroyers. As one historian put it, “An inferior, cargo-entangled and partially surprised destroyer squadron had demolished a superior cruiser-destroyer group.” In spite of this success, Tanaka had not done what he had set out to do—deliver supplies to the troops on Guadalcanal. Not a single drum of much-needed food or medicine reached the starving Japanese soldiers.

Admiral Tanaka tried again a few nights later and succeeded in unloading about 1,500 drums at Tassafaronga Point. Only about 300 of the drums were actually hauled onto the beach, however. The others floated out to sea. The third attempt was a total failure. Air strikes and aggressive attacks by U.S. PT boats forced the Japanese destroyers to turn back without delivering any supplies.

Starvation Island

By mid-December, the Japanese Navy was ready to cut its losses and cede Guadalcanal to the Americans. Senior naval officers were not prepared to lose any more ships or men in what had become a totally futile campaign. Also, the drum method of supplying the garrison had turned out to be another waste of time and another drain on their overtaxed resources.

The Army General Staff did not agree. The generals still hoped that a new offensive would dislodge the Americans from the island, although some of the more realistic leaders were trying to concoct a way of withdrawing without making it seem like a defeat.

A communiqué from Lt. Gen. Harukichi Hyakutake, the commander of the Japanese Seventeenth Army on Guadalcanal, seemed to bring the matter to a head. On December 23, Hyakutake informed Tokyo of the desperation on Guadalcanal. “No food available and we can no longer send out scouts. We can do nothing to withstand the enemy’s offensive. Seventeenth Army now requests permission to break into the enemy’s positions and die an honorable death rather than die of hunger in our own dugouts.”

The General Staff finally faced the reality of what the men on Guadalcanal were suffering on a daily basis. Hyakutake’s men had drawn up their own method of determining how long a man might survive on Starvation Island:

“He who can rise to his feet—30 days left to live

He who can sit up—20 days left to live

He who must urinate while lying down—3 days left to live

He who cannot speak—2 days left to live

He who cannot blink his eyes—dead at dawn.”

The Decision to Withdraw

Two days after Hyakutake’s sobering message arrived, senior Army and Navy officers held an emergency meeting at the Imperial Palace to work out the details of the withdrawal from Guadalcanal. The Navy blamed the Army for not making better use of the men and equipment they had been given. The Army blamed the Navy for not supplying enough food and ammunition for the troops.

“You landed the Army without arms and food and then cut off the supply,” one officer complained. “It’s like sending someone on a roof and taking away the ladder.”

The arguing went on for four days, until a staff officer named Colonel Joichiro Sanada arrived from Rabaul with a recommendation regarding Guadalcanal. The recommendation was that all troops should be taken off the island as soon as possible, and it had been endorsed by every Army and Navy officer in the Solomons who had been consulted. To examine the situation even further, war games were held to explore what might happen if an attempt to strengthen the Guadalcanal garrison was carried out. War gaming reached the same conclusion—in the course of the games, American air and naval forces destroyed any convoys attempting to resupply or reinforce Guadalcanal.

The participants were convinced that the island could be recaptured from the Americans only by a miracle. Colonel Sanada’s report, when added to the weight of Hyakutake’s communiqué and the results of the war games, ended the bickering between the Army and the Navy. Both sides jointly decided that Hyakutake’s men should be evacuated from Guadalcanal by the end of January.

Operation KE: The Evacuation of Guadalcanal

Before anything else could be accomplished, Emperor Hirohito would have to be informed of the planned evacuation. An audience with the emperor was arranged for December 31. This was a job that no one relished. His Majesty was not at all happy to hear that his Army and Navy had been unable to drive the detested Americans from Guadalcanal in spite of more than four months of exhausting effort. One item that particularly irked Hirohito was why Japanese construction units needed more than a month to build an airfield while the Americans had completed their unfinished work in just a few days.

It was an especially pertinent question, the emperor thought, because American airpower was largely responsible for the impending Japanese loss of Guadalcanal. The enemy always seemed to have more planes, both carrier based and land based, than the Japanese. The Americans had an advantage, Hirohito was told. They used machines, while their own construction units were forced to use manpower to do the job. The emperor did not seem to be satisfied by this explanation and continued to ask pointed questions for another two hours.

The interview eventually came to an end, to the relief of everyone present. Hirohito concluded the meeting by urging both the Army and Navy to do better in the future. Reluctantly, but realizing that there was not much else he could do, the emperor approved the withdrawal of all Japanese forces from Guadalcanal. It was now official and sanctioned by His Majesty. Guadalcanal would be relinquished to the Americans.

Throughout December, American intelligence was becoming increasingly convinced of one thing: the Japanese were preparing for another major offensive to retake Guadalcanal. On December 1, an analyst at CINCPAC (Commander in Chief Pacific) observed, “It is still indicated that a major attempt to recapture Cactus [Guadalcanal] is making up.”

It certainly looked as though some sort of attack was in the offing. Admiral Tanaka’s attempts to reinforce the Guadalcanal garrison appeared to be strong evidence. Also, Japanese warships and cargo vessels were congregating at Rabaul, a clear sign that an attack was imminent. Seventy ships had anchored in the harbor by late December.

There were other telling signs. On New Year’s Day 1943, Japanese cryptanalysts changed their radio codes, making it difficult for intelligence to gather information regarding enemy intentions—at least until the code was broken again. Also, the volume of radio traffic had increased dramatically. Evidence of an enemy buildup was unmistakable, and it was not taking place just at Rabaul. Truk and the Shortland Islands were also receiving significantly larger numbers of ships and aircraft.

Throughout December and January, intelligence enthusiastically gathered information on Japanese activities, making detailed notes on the increased enemy movements and reaching their conclusions—and the conclusions being reached were absolutely, totally wrong. An intelligence communiqué dated January 26, 1943, informed all Allied forces that Japan was preparing a new assault in either the Solomons or New Guinea. This new campaign would be called Operation KE and would probably begin in the next few weeks.

Actually, the communiqué was not totally incorrect. Imperial general headquarters in Tokyo had created an operation code-named KE, but it had nothing to do with recapturing Guadalcanal. In fact, Operation KE was the codename for the evacuation of all Japanese troops from Guadalcanal, which was to take place beginning in mid-January. Allied intelligence analysts had completely misread Tokyo’s intentions.

“A Trail of Corpses”

Basically, Operation KE was divided into two parts. First, an infantry battalion would be landed on Guadalcanal in mid-January. These men would serve as a rearguard unit to keep American forces pinned down while Seventeenth Army escaped. Provisions and supplies for about three weeks were to be landed at about the same time. When the rearguard unit was in place, phase two, the evacuation itself, would begin. Most of the men would be taken off the island by destroyers—the Tokyo Express in reverse. Some of the troops would be transferred to landing craft. Submarines would stand by to pick up anyone left behind.

While all this was taking place, several diversions would keep the Americans guessing as to the Japanese Navy’s real intentions. Port Darwin in Australia was to be bombed in a night air raid, the cruiser Tone and submarines were to shell American bases east of the Marshall Islands, and fake radio traffic in the Marshalls would fool American eavesdroppers into thinking that some sort of action would take place there. The target date for the completion of Operation KE was February 10, 1943.

The Japanese Navy continued its Tokyo Express runs throughout the month of January and had some successes in spite of interference from American aircraft and PT boats. The run of January 3, for instance, landed about five days of supplies that were brought ashore in drums and rubber bags. On January 14, nine destroyers carried the Yano Battalion to Guadalcanal—750 men and a detachment of artillery under the command of Major Keiji Yano to serve as the rear guard.

One of the officers who accompanied the Yano Battalion was Lt. Col. Kumao Imoto. Imoto had also been given an unenviable job—delivering the evacuation orders and plan to General Hyakutake in person. The assignment turned out to be just as distasteful as he had thought. He disembarked near Cape Esperance after dark and found dead bodies throughout the area.

“The trail that led to Seventeenth Army headquarters was a trail of corpses,” Imoto said. At around midnight, after a harrowing walk from the beach, he finally arrived at Hyakutake’s camp.

The two officers whom Imoto first met expected to be given an attack plan, not orders to evacuate, and were surprised when they were told of the command to pull out. At first, they refused to accept the orders, and only grudgingly accepted after being told that they had come from the emperor himself. After this unpleasant exchange, Imoto was taken to see General Hyakutake.

Hyakutake was sitting on a blanket under a large tree when Imoto found him. He stared wordlessly for a minute or so after being given the withdrawal order; he had obviously been taken completely by surprise as well and needed time to recover. “The question is very grave. I want to consider the matter quietly and alone for a little while,” he slowly said to Imoto. “Please leave me alone until I call for you.”

For the next several hours, Hyakutake thought about Operation KE and what it meant. He also conferred with General Shigesaburo Miyazaki, one of the officers who met Imoto when he arrived at the camp. Miyazaki did not like the idea of abandoning Guadalcanal and preferred an all-out attack against the Americans instead. Hyakutake had a choice to make: order an attack or obey the emperor’s orders. At around noon, he sent for Imoto to give his reply.

“It is very difficult for the Army to withdraw under existing circumstances,” he said. “However, the orders of the Area Army, based upon orders of the Emperor, must be carried out.” He went on to say that he could not guarantee that the withdrawal “can be completely carried out.” Hyakutake agreed to obey Hirohito’s command but did so reluctantly.

The Capture of Kokumbona

The details of Operation KE were given to the various units of Seventeenth Army on January 18. Many officers and men were almost violent in their opposition to the operation; they had no wish to leave wounded and sick comrades behind while they left Guadalcanal for their own safety. But senior commanders realized that the order would have to be obeyed, no matter how they opposed it personally.

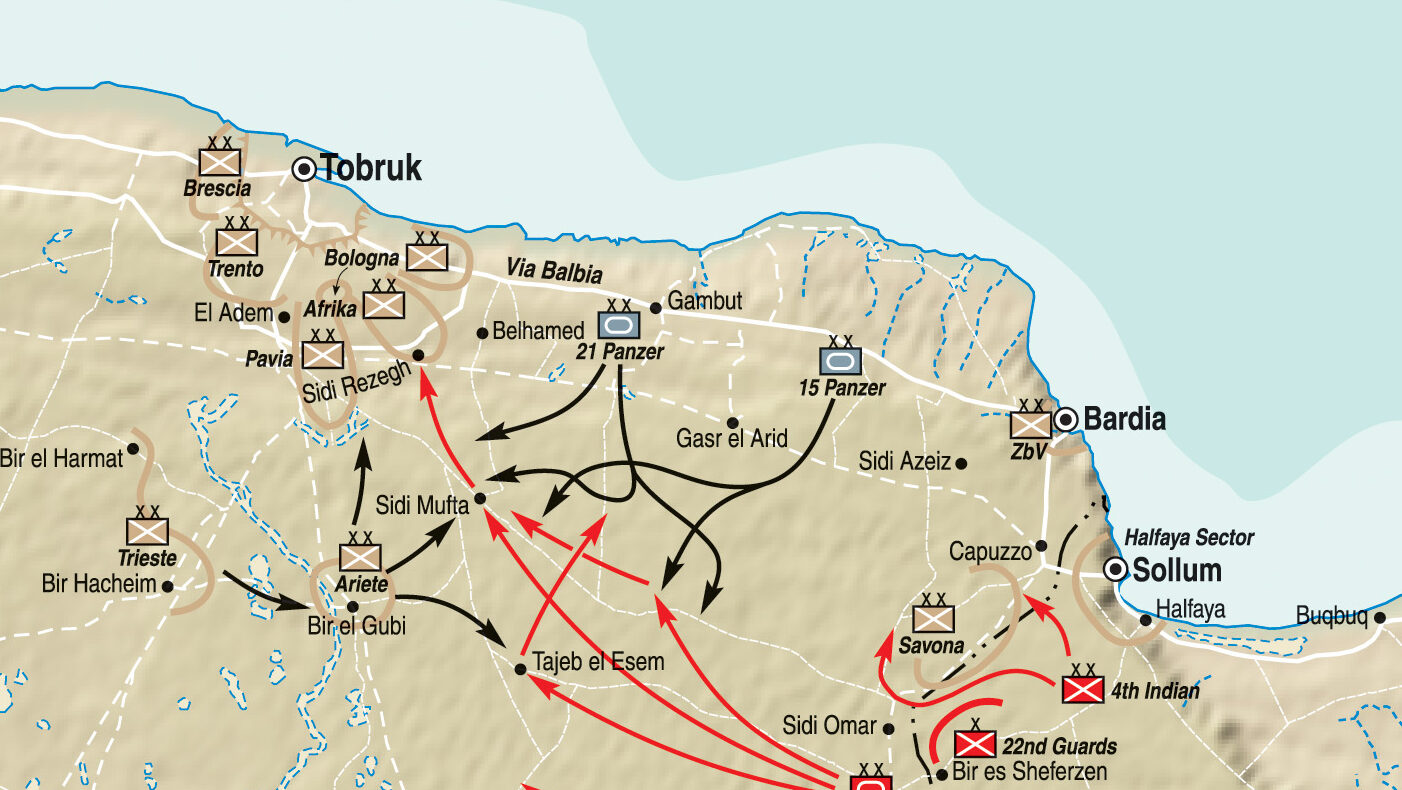

According to the directive, the first unit to withdraw was the 38th Division, but the 38th had been fighting an American offensive, ordered by Maj. Gen. Alexander M. Patch, the commander of all forces on Guadalcanal, since January 10. General Patch had resolved to force the enemy off Guadalcanal and drive him into the sea at about the same time that Tokyo had ordered Operation KE. The goal of the attack was to capture Galloping Horse Hill, a position so called because on the map it resembled a running horse, and two other positions called the Sea Horse and Gifu. All of these objectives were south of Point Cruz.

The defenders of Gifu put up the most determined resistance, including a suicide charge at the Americans on January 17. In spite of this, American troops overran the position the next day. The Sea Horse had been taken on the 16th, and Galloping Horse Hill on January 13. General Patch next set his sights on the Japanese base at Kokumbona.

A column of four U.S. destroyers, Radford, DeHaven, Nicholas, and O’Bannon, had been sent to bombard enemy positions near Kokumbona in advance of the attack. Among them, the destroyers fired several hundred rounds of five-inch ammunition throughout the night of January 19, while engineers built a road past Galloping Horse. Units of the 25th Division began advancing toward Kokumbona via the Galloping Horse road, while a composite Army-Marine unit moved along the coastal road.

Japanese defenders did their best to stop the Americans, but the combination of the attacking troops, artillery support, destroyer gunfire, and air bombardment proved to be too much. American troops fought their way through and reached Kokumbona on January 23, but when they arrived they discovered that most of the Japanese had left. None of the Americans, from General Patch to the lowest private, had any idea that the retreating Japanese troops were on their way to Cape Esperance, where they would wait to board destroyers and evacuate Guadalcanal.

Because he feared that a major Japanese attack was in the offing, General Patch would not commit all of his forces in the area to pursuing the retreating Japanese west of Kokumbona. The combined Army-Marine unit ran into the Yano Battalion. The rear-guard unit certainly did its job. Yano and his men stopped the Americans, at least temporarily, and continued to withdraw westward toward Cape Esperance. On January 29, the battalion crossed the Bonegi River and dug in. The defenders held off American troops at the Bonegi for another three days before pulling back. American units cautiously pursued them.

Intercepting the Japanese “Reinforcement Unit”

By this time the Japanese Navy had already begun its evacuation effort. Twenty-one destroyers left their base in the Shortland Islands on January 31 to start their first evacuation run to Guadalcanal. Rear Admiral Shintaro Hashimoto commanded the destroyers, which had been given the misleading name “Reinforcement Unit” in case any American eavesdroppers became aware of them.

Besides Admiral Hashimoto’s destroyers, a support unit made up of the heavy cruisers Chokai and Kumano along with light cruiser Sendai would be standing by. Floatplanes served as a sort of aerial advance guard for Hashimoto’s destroyers, attacking any American ships threatening to interfere during daylight hours. The entire 11th Air Fleet would also be on hand if needed.

After the destroyers sailed, the first non-Japanese who saw them were the coast watchers on the islands north of Guadalcanal. During the early afternoon hours of February 1, word was sent that a column of Japanese destroyers, a dozen or more, was coming south down the Slot at high speed. It looked as though this was the major Japanese attempt to land more troops. Nicknamed the Cactus Air Force, U.S. planes based on Guadalcanal reacted aggressively. A force of 17 Douglas SBD Dauntless dive-bombers and seven Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bombers escorted by 17 Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters took off from Henderson Field and headed for the Japanese destroyers.

Japanese fighters shot down four of the attackers, but one of the SBDs put a bomb close alongside Hashimoto’s flagship, Makinami. The near miss did not sink the destroyer, but it did slow her down and put her out of action. Hashimoto transferred his flag to the destroyer Shirayuki and detached Fumikaze and another destroyer to escort Makinami back to base.

The rest of the Reinforcement Unit continued toward Guadalcanal at a steady 30 knots. At about 10:10 pm, two PT boats in the vicinity of Savo Island attacked the destroyers. A short while later, another five PTs came after Hashimoto’s force. With a bit of luck and some help from floatplanes, no damage was done. Three of the torpedo boats were sunk.

At 10:40, the transport destroyers reached their objective. Boats were lowered to ferry troops from the beach to the ships. The ships were filled just before 2:20 am on February 2, and the destroyers set a course for Bougainville with 4,935 men aboard.

Crew members on board the destroyers were horrified by the condition of the evacuees. An officer reported that the men “wore only the remains of clothes … so soiled [that] their physical deterioration was extreme. Probably they were happy but showed no expression. All had dengue or malaria … diarrhea sent them to the heads. Their digestive organs were so completely destroyed [we] couldn’t give them good food, only porridge.” The reason that Guadalcanal was known as Starvation Island was readily apparent.

The first evacuation run had been a success in spite of the fact that one of the destroyers had been struck by either a PT torpedo or mine and had to be scuttled. Thousands of troops remained on Guadalcanal.

The Second Evacuation Run

A second evacuation run set sail from the Shortland Islands at 11:30 pm on February 4. Hashimoto’s Reinforcement Unit consisted of 20 destroyers, including two replacements. Once again, coast watchers warned Guadalcanal of the approaching destroyers and, once again, the Cactus Air Force came out to stop them. Zeros flying defensive cover shot down 11 of the attackers in exchange for one of their own destroyed and three damaged. Admiral Hashimoto also had his flagship shot out from under him for the second time and was forced to transfer his flag. His new flagship was the destroyer Kawakaze.

The destroyers reached the coast of Guadalcanal without any interference from American PT boats. Everything seemed to go right, and only two hours were needed to embark 3,921 men aboard the transport destroyers. Among the evacuees were General Hyakutake and his staff. The trip to Bougainville was just as fast and efficient as the loading had been. Hyakutake and the entire Reinforcement Unit reached the safety of Bougainville on February 5 without incident.

So far, Operation KE had not only been successful but was also still a secret. American officers on Guadalcanal were convinced that the Japanese activities in early February were reinforcement actions. In fact, General Patch gave his opinion that the last two Tokyo Express trips had landed a full regiment along with their supplies and equipment. Because he was convinced that the Japanese forces had been strongly reinforced, Patch ordered his troops to proceed cautiously. He had no intention of falling into a trap and was not upset by the fact that his men were advancing only about 900 yards each day.

The 161st Regiment was only about nine miles from Cape Esperance on February 7. If Patch had been aware that Hashimoto was evacuating Japanese troops, he would certainly have ordered a full-scale attack on what was left of Hyakutake’s forces.

The Third and Final Run

While General Patch was worrying that more Japanese troops were being put ashore, Hashimoto was beginning his third evacuation run. Hashimoto had worries of his own as he prepared for this run to Guadalcanal. Even though the second venture had been fairly straightforward and uneventful, Hashimoto decided to set a course along the southern rim of the Solomons instead of steaming directly down the Slot. He did not want to tempt the gods of war or the Cactus Air Force.

The precaution did not prevent harassment by American bombers. Hashimoto’s Reinforcement Unit came under attack by 36 aircraft—SBDs and fighters—but the air strike was once again intercepted by Zeros. The dive bombers did manage to damage one of the destroyers. Isokaze was rattled by two near misses and was escorted out of the area by another destroyer. The other 16 ships reached Guadalcanal without further mishap and began taking aboard the remaining Japanese troops. Embarkation went quickly and efficiently. Just after midnight on February 8, 1943, boarding was completed. A total of 1,972 men were taken aboard the destroyers. Some of the soldiers were too weak to climb the rope ladders and had to be pulled aboard by sailors.

Before departing Guadalcanal, sailors from the destroyers rowed small boats just offshore, shouting and calling out to anyone who might have been left behind. This went on for an hour and a half, until Admiral Hashimoto was satisfied that every Japanese soldier who was able and willing had been evacuated. Finally, at about 1:30 am, all the boats had returned to their mother ships.

Hashimoto ordered the Reinforcement Unit to set course for Bougainville by the most direct route, straight up the Slot at 30 knots. Eight and a half hours later, after a completely uneventful trip, the 16 destroyers arrived at their base. The officer in charge of the rearguard echelon, a Colonel Matsuda, reported the formal end of Operation KE to General Hyakutake.

Over 10,000 Escaped

A total of 10,828 men had been taken off the island in three evacuation runs. This was far more than Imperial Headquarters in Tokyo had expected or even hoped for. Senior officers, both Army and Navy, greeted the news with relief. But the good news was tempered with some misgiving. It was pointed out that the troops were in such poor physical condition that many months of training and rehabilitation would be needed before they would be fit for duty again. Some of them would never be able to return to duty. The physical and mental strain of their time on Guadalcanal would take a permanent toll.

A few hours after Hashimoto left Guadalcanal for the last time, the U.S. 161st Infantry resumed its cautious advance toward Cape Esperance. The GIs met virtually no resistance; the Japanese rear guard was already halfway to Bougainville. Only troops who could barely walk, let alone fight, stood between the Americans and Cape Esperance. The officer in command took stock of the situation and reached the conclusion that the enemy had abandoned Guadalcanal.

When reports from western Guadalcanal reached General Patch, the truth finally dawned on him. The Tokyo Express had been removing troops from the island, not replacing them. On the following day, February 9, two units of the 161st met at the village of Tenaro, a few miles southeast of Cape Esperance. If any further proof was needed to show that all able Japanese troops had left the island, this link-up provided it.

Patch informed Admiral William F. Halsey, U.S. Commander in the South Pacific Area, “Total and complete defeat of Japanese forces on Guadalcanal effected 1625 today … ‘Tokyo Express’ no longer has terminus on Guadalcanal.”

“Victory was Ours”

The skill and cleverness with which the Japanese forces had been withdrawn, right under the noses of American troops and naval forces, became the subject of praise even from the Americans. In his official report, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander in chief of U.S. naval forces in the Pacific, was forced to state his admiration for Operation KE.

“Until the last moment, it appeared that the Japanese were attempting a major reinforcement effort,” Nimitz wrote. “Only skill in keeping this plan disguised and bold celerity in carrying it out enabled the Japanese to withdraw the remnants of the Guadalcanal garrison. Not until all organized forces had been evacuated on 8 February did we realize the purpose of their air and naval dispositions.”

Very little criticism was ever leveled at American commanders for allowing Hyakutake and most of his army to escape. Hyakutake was convinced that an attack by Patch’s forces would probably have wiped out Seventeenth Army. Admiral Halsey did receive some criticism for not taking stronger measures to stop Hashimoto and his three sorties with the Reinforcement Unit. The main reason that neither Patch nor Halsey received an official reprimand for letting Operation KE succeed is that Japanese intentions had been so completely misinterpreted. They simply acted on the information they had been given.

The New York Times lead story on February 10, 1943, fairly crowed, “Every American heart must have thrilled yesterday at the news that the battle of Guadalcanal was over and the victory was ours.” After six months of fighting, America had won. The country was in the mood for celebrating, not for placing blame or finding fault.

“Their Mission Had Been Fulfilled”

On the other hand, the Japanese struggled to make the best of a bad situation. The Japanese public was given the story that all troops had been withdrawn from Guadalcanal because “their mission had been fulfilled.” Japanese soldiers on Guadalcanal were portrayed as having an indomitable spirit for holding on so long under such adversity. Although this line did keep Japanese civilians from learning the truth, Tokyo was not able to turn Guadalcanal into a great moral victory.

Senior Japanese military officers knew all too well that Guadalcanal had been a military failure of the first order, but they also did their best to look at the positive side of the campaign. The success of Japanese destroyers against American warships in combat and as the main components of the Tokyo Express was seen as a victory. Hashimoto rightly received high praise for the way he managed the evacuation.

Japan never recovered from the losses of men and ships suffered at Guadalcanal. A former Japanese naval officer told author Richard B. Frank, “There were many famous battles in the war—Saipan, Leyte, Okinawa, etc. But after the war we talked about only two, Midway and Guadalcanal.”

From all my reading and study of the Pacific naval war, I feel adm. halsey dropped the ball big time late in the forth quarter f the war. He cost the unneeded loss of two destroyers in a storm and many other bad calls. Unneeded loss of US lives is his post war score…!

Gregory Pischea, USN/USMC Ret.

Perhaps, but Adm. Halsey’s mission, whether official or not, was to destroy Japanese heavy naval forces.

considering the tempo of operations, and the gargantuan nature of the Fifth Fleet, it seems to me that Halsey’s judgement was adversely affected by fatigue. You can see it in the photos of the Admiral from the time. Marc Mitscher and Ghormley (Guadalcanal) were pretty much in the same state.

After America destroyed Japan’s navy at Midway, it was unable to adequately supply its soldiers in remote outposts. Those Japanese soldiers lacked food, fuel, ammunition, medical supplies, reinforcements, etc. That meant that it was impossible for them to halt the endless onslaught of well equipped & well supplied American troops that were heavily supported with both naval & air power. Those island hopping massacres near the end of the War were lop-sided battles.

The last sentence is the key to future strategic thinking. After Midway and Guadalcanal, circa February 1943, the Japanese High Command knew they could not win the war they started at Pearl Harbor, on Dec 7, 1941. Yet they let their nation be destroyed by continuing a hopeless struggle. Millions died for no reason.

Leaders, on all sides, should consider this before entering another mindless war in the era of thousands of thermonuclear weapons. The war weapons of WWII are closer to a pea shooter than what several nations now possess. The concept of victory has little meaning if every body dies.

Come. Let us reason together.

Happy New Year.

While I was growing up, I learned that there wasn’t any reasoning with some people. So, I learned to defend myself and my friends. Later in life, I learned that all people fall far from the Glory of God. Our very nature is sinful and without God we are hopeless to change. Therefore, we need to expect “mindless wars” and always be prepared for war. Just like the good old days on the playground.

It would appear that the Japanese who had been on mainland China and Korea for a number of years, had not fully developed the logistic programs necessary to operate on the newly acquired Pacific islands after WW I. Defending an island with the enemy surrounding, as MacArthur discovered earlier, is quite a monumental task requiring a high level of preparation.

The Guadalcanal campaign was truly the turning point of the war with Japan as opposed to the Battle of Midway. While several Japanese aircraft carriers were sunk, along with many planes and experienced pilots, and the small, remote island of Midway was successfully defended, the removal of all Japanese military personnel from Guadalcanal was arguably the most important battle of the PTO and had the highest strategic significance in the long run. Had the Japanese gained complete control of the island with its unsinkable airstrip, they could have severely and significantly interfered with the flow of war materiel between the United States and Australia and even put the latter in danger of being invaded by Japanese troops. Stopping and removing the Japanese from Guadalcanal provided the Americans and Australians with a large, effective air base for air operations to help kept the sea lanes open to Australia and prevent any Japanese attempt to invade that country.