By Michael D. Hull

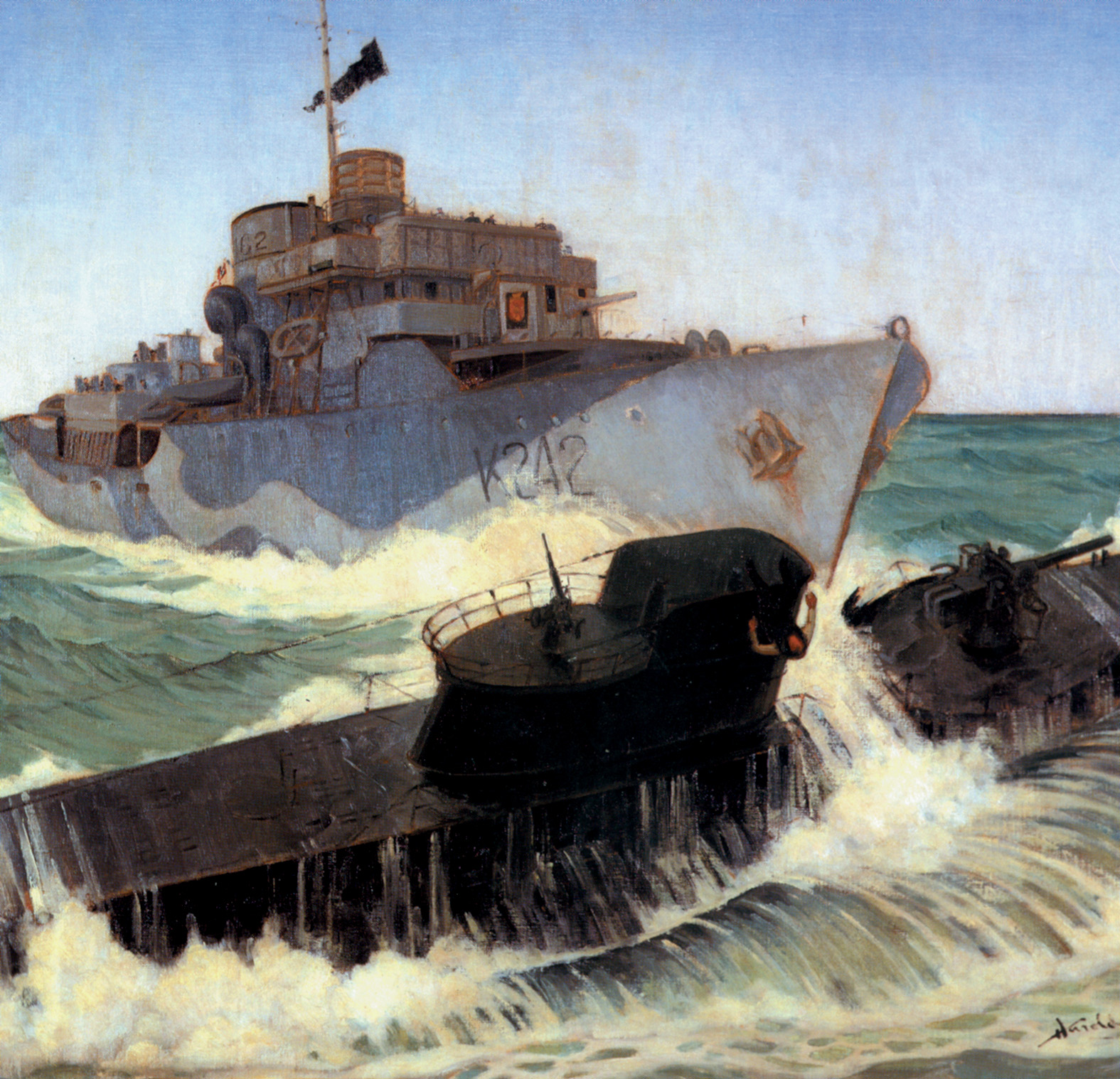

When Chancellor Adolf Hitler started rearming Germany in 1934, his submarine force commander, Admiral Karl Doenitz, asked for men and materiel to create a fleet of 300 U-boats.

With such power, he told the Führer, Germany could dominate the high seas, challenge the Royal Navy’s traditional superiority, choke off commerce, and starve the British into submission in six months. But the leaders of the Wehrmacht and the Luftwaffe doubted Doenitz’s contention, and Hitler had higher priorities on his mind.

So, when World War II broke out early in September 1939, Doenitz commanded only 56 boats. He believed that if he were given the resources he needed, he could defeat Britain by 1943. Nevertheless, with only a dozen submarines operational at any one time, his force sank 199 merchant ships and a third of the British battleship strength in the first months of the war. And, in December 1941, six U-boats sank half of the total registered U.S. tonnage.

By early 1943, Doenitz had 200 U-boats operating in “wolfpacks” and 181 in production. He was responsible for sending 15 million tons of Allied shipping to the bottom, but, after vicious battles in March 1943, the Allied convoy escorts gradually gained the upper hand in the North Atlantic.

By early 1943, Doenitz had 200 U-boats operating in “wolfpacks” and 181 in production. He was responsible for sending 15 million tons of Allied shipping to the bottom, but, after vicious battles in March 1943, the Allied convoy escorts gradually gained the upper hand in the North Atlantic.

When the U.S. Navy joined forces with the British and Canadian fleets, the outcome was resolved. In the end, as Edwin P. Hoyt writes in The U-Boat Wars (Cooper Square Press, NY, 2002, 242 pp., 32 photographs, map, notes, index, $17.95 softcover), British perseverance and American productivity overcame German aggression and technological skill. Drawing on German, British, and American archives, this, like Hoyt’s many other war books, is a crackling narrative. It is factual, fast-paced, and gripping. He brings history alive and is always fresh and never dull.

The author points out that First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill realized at the outset of the war the calamitous situation facing Great Britain. He remembered only too well that sinkings by U-boats had brought his country to within three weeks of starvation in 1917. So, when he became prime minister in the spring of 1940, Churchill set up a cabinet committee to address what he perceived correctly as the chief menace of the war. As he said later, “The only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril.”

As terrible as the threat was, says Hoyt, the British were in position to respond to attacks throughout the war. Every German challenge was overcome, and 807 of Doenitz’s 1,150 commissioned submarines were destroyed. During the last two years of the war, British, American, and Canadian destroyers, frigates, and aircraft kept the wolfpack predators in check while the three nations’ armies moved steadily toward the heart of Germany.

The author points out that the U-boat crews were the most dedicated and most tragic of all military forces engaged in World War II. Of a total of 39,000 men in the German boats, 28,000 were killed in action and 5,000 captured, a casualty rate of 85 percent. The Atlantic campaign, the longest of the war, was a struggle of deadly enemies and heroes against heroes.

When We Were One by W.C. Heinz, Da Capo Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2002, 264 pp., $23 hardcover.

When We Were One by W.C. Heinz, Da Capo Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2002, 264 pp., $23 hardcover.

Some reporters covered World War II from briefing rooms at Army headquarters or from hotel bars in Paris or Cherbourg, but W.C. Heinz got as close to the fighting as the brass and good sense would let him.

After spending a month and a half as the New York Sun’s junior war correspondent aboard the escort carrier USS Core in the Atlantic Ocean in the fall of 1943, the Middlebury (Vermont) College graduate packed his portable Remington typewriter and headed for London in April 1944 to cover the Allied invasion of Normandy.

Following the ground war through northwest Europe, Wilfred Charles Heinz learned about courage, cowardice, and truth, and how men in foxholes fight for one another rather than causes. Heroism is a kind of love, he discovered. He stripped all artifice from his work, and a unique style emerged — a tight, refined, crystal prose that would earn him praise from the likes of Ernest Hemingway and Damon Runyon. What Heinz’s readers got was pure story.

In spite of the censors, for much of what he saw he could not report, his dispatches — many of them collected in this book — were gems of narrative power that distilled all the horror of combat as the Allied armies pushed eastward to the Rhine and beyond. When the Sun’s senior correspondent was captured by the Germans, Heinz replaced him. After getting a bellyful of cordite and fear, waste and cruelty, panic and ineptitude, Heinz found himself on the verge of a nervous breakdown by September 1944. However, he managed to hang on through the Battle of the Bulge and the big push to Berlin, and came home in June 1945.

He later became a topflight sportswriter, specializing in boxing, and wrote about such legends as Red Grange, Stan Musial, Jack Dempsey, Gene Tunney, Joe Louis, Rocky Graziano, Willie Pep, Sugar Ray Robinson, Tony Zale, Archie Moore, Vince Lombardi, and Eddie Arcaro.

This is the first time that Heinz’s war writing has been collected in one volume, and it is a dramatic first-person record of the war: tensions on the bridge of the battleship USS Nevada on June 6, 1944; an infantry captain breaking down while recounting the bravery of his men during 39 consecutive days of action; a moonlight jeep ride in Belgium with a major who was later killed; the wintry hell of the Hürtgen Forest and the Ardennes; the execution of three German spies; and a poignant return to Omaha Beach with Colonel James E. Rudder of the U.S. 2nd Ranger Battalion.

Heinz, who now lives in Dorset, Vermont, is a survivor of a bygone era when journalism was a respected craft, and this eloquent, touching little book proves that he was one of its consummate practitioners.

Mussolini by Richard J.B. Bosworth, Oxford University Press, NY, 2002, 584 pp., 27 photographs, maps, notes, index, $35 hardcover.

Mussolini by Richard J.B. Bosworth, Oxford University Press, NY, 2002, 584 pp., 27 photographs, maps, notes, index, $35 hardcover.

With a degree of venom that a gentleman occasionally disgorges, British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden observed early in World War II, “Mussolini is, I fear, the complete gangster, and his pledged word means nothing.”

Yet, at the September 1938 Munich Conference that Italian dictator Benito Mussolini had skillfully orchestrated, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain had been impressed with the Duce’s “quiet and reserved manner.” Chamberlain visited Rome in January 1939 to try to utilize the good offices of Mussolini to reach the enigmatic German Chancellor Adolf Hitler with a final plan for averting war. The British prime minister remained optimistic and reported that the Duce looked “well” and possessed “a strong sense of humor and an attractive smile,” while being “pleasant in conversation.”

But history has been less merciful to the flamboyant, bull-necked man who inspired Hitler with his Fascist Party and dominated Italy for more than two decades, and he has been generally characterized as a strutting, boastful, incompetent, and promiscuous buffoon—a “Sawdust Caesar.” He was a fraud, said eminent historian A.J.P. Taylor, and the revolution by which he seized power in 1922 was a fraud.

In this exhaustive, lucid, and persuasive biography, Richard Bosworth points out that, despite the brutal Italian invasion of Ethiopia, the murderous “pacification campaign” in Libya, a massive intervention in the Spanish Civil War in 1936, race laws that doomed Italian Jews, and the sinister alliance with Germany, Mussolini was the least malevolent and destructive of the war’s dictators. He was no Hitler, Stalin, or Tojo, says the author, and “not so vicious that history should relegate him, frozen, to the bottom most circle of a Dantesque hell.”

The Duce was “a man for all that,” bogus in some ways, but not a mere clown, and brutal but not altogether inhuman. He had a talent for manipulating men, women, and domestic politics, but was increasingly out of his depth in international affairs.

Bosworth, a history professor at the University of Western Australia, has produced a solid, insightful, and stylish study of a man whose personality was as complex as that of Winston Churchill. Mussolini kept the works of Socrates and Plato on his desk, loved sports and trees, could converse in three languages other than his own, and claimed with an element of truth that money had never dirtied his hands.

Bosworth shows how the Duce became Hitler’s junior partner and how his dispirited forces swiftly disintegrated at the hands of the Allies. His desert army was humiliated by a minor British force in December 1940, his invasion of Greece from Albania in November 1940 was even more disastrous, he lost the bulk of his army in Tunisia in 1943, and his expeditionary force on the Eastern Front was destroyed.

Mussolini governed by charisma, and his propagandists declared that he was always right. However, the author concludes, in the most profound matters that touch on the human condition, he was, with little exception, wrong. Crafted with measured assessment, sympathy, and occasional admiration, this is a masterful study.

Beyond Valor by Patrick K. O’Donnell, Touchstone Books, NY, 2002, 366 pp., photographs, 11 maps, appendices, index, $14 hardcover.

Beyond Valor by Patrick K. O’Donnell, Touchstone Books, NY, 2002, 366 pp., photographs, 11 maps, appendices, index, $14 hardcover.

From the first parachute drops in North Africa in November 1942 to the final battles in Germany in the spring of 1945, the U.S. Army’s crack Airborne and Ranger units played key roles and often were engaged in the costliest actions of World War II.

They helped to clear the Axis forces out of Tunisia, aided in saving the Sicily and Salerno beachheads, broke the stalemate on Italy’s Winter Line, facilitated the breakthroughs off Omaha and Utah Beaches, spearheaded the invasion of Holland, helped to turn the tide in the Battle of the Bulge, and made the final plunge into Germany.

The Airborne branch was the largest of the American elite units, and its 101st and 82nd divisions distinguished themselves—with heavy losses—wherever they served. The 101st made Bastogne a proud name in military history, while the 82nd was described by General Miles Dempsey, commander of the British Second Army, as “the greatest division in the world today.”

Conceived by Generals George C. Marshall and Lucian K. Truscott and trained by the British Commandos in Scotland, Major William Orlando Darby’s U.S. Ranger battalions covered themselves with glory in North Africa, Sicily, Italy, and Normandy. Less well known but equally gallant was Lt. Col. Robert Frederick’s 1st Special Service Force (the North Americans), composed of U.S. and Canadian volunteers, which played decisive roles in the Italian and Southern France campaigns.

The collective story of these units’ exploits unfolds in this enlightening and highly readable anthology. Patrick O’Donnell has woven 650 eyewitness accounts by veterans into a seamless narrative that will grip any reader. Frontline experiences are recalled with pain, poignancy, and pride in an honest and unvarnished manner. Hidden horrors and uncelebrated heroics are brought to light to underscore the dedication and sacrifice of a breed of GIs who went willingly in harm’s way to help preserve freedom.

The author includes reminiscences by six veterans of the all-black 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion (the “Triple Nickels”), which trained late in the war and wound up fighting forest fires in the Northwest.

While an unpretentious little volume, this is nevertheless a work of considerable power.

The Last Kilometer by A. Preston Price, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 2002, 202 pp., 10 photographs, 2 maps, index, $24.95 hardcover.

The Last Kilometer by A. Preston Price, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 2002, 202 pp., 10 photographs, 2 maps, index, $24.95 hardcover.

“Now, up the street, I can see that the head of our column is turning right on the main highway leading to the south. It is the highway that leads to the city of Altenkirchen…. We are launching our attack on Fernegierscheid.

“As I reach the main highway, I notice the body of a German soldier lying in the center of the road. A tank has evidently run over his body, as he is flattened like a pancake. His skin is yellow from the thick dust that covers him…. At the bottom of the hill, we march past one of our light tanks, which is burning fiercely, having been neatly pierced by German tank fire. The body of one of our tankers lies near it. A few yards further, we see another tank burning. This has been a regular shooting gallery for some German tanker.

“We all have the feeling that the German may have us in his sights, and the column increases its pace on the exposed portions of the road. No one has to remind us to keep our five-yard intervals.”

From foxhole to foxhole, plodding through dust and mud and snow, and dodging shells and machine-gun fire, the eternal plight of the dogface foot soldier is retold in a graphic and powerful little memoir by Arthur Preston Price, who marched through northwest Europe as a lieutenant and 81mm mortar forward observer with the 26th Infantry Regiment of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division during the final six months of World War II.

It is a stirring saga of U.S. infantrymen, but devoid of drum-and-bugle glorification. Rather, it is a chronicle of hardship and dirt, fear and fatigue, blood and sacrifice. Clear, precise, and well paced, Price’s memoir is understated and fully authentic.

He takes the reader along on the advance with the famed Big Red One from November 1944 to May 1945, from Le Havre and through France, Belgium, and Germany, into action in the Roer River and Remagen bridgehead campaigns, across the Siegfried Line dragons’ teeth, attacking in the Harz Mountains, and on to liberate the Czechs. This is a literate and riveting tribute to the 44,000 men who served in the Big Red One. Almost half of them were casualties by war’s end, and more than 20,000 earned decorations, including 16 Medals of Honor.

Price was a strategic intelligence officer after the war, and taught at The Citadel and at high schools in El Paso, Tex., where he lives.

Warrior Queens by Daniel Allen Butler, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, Pa., 2002, 191 pp., 17 photographs, appendix, index, $26.95 hardcover.

Warrior Queens by Daniel Allen Butler, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, Pa., 2002, 191 pp., 17 photographs, appendix, index, $26.95 hardcover.

“Built for the arts of peace and to link the Old World with the New, the Queens challenged the fury of Hitlerism in the Battle of the Atlantic,” said British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. “Without their aid, the day of final victory must unquestionably have been postponed.”

He was paying tribute to the great liners, Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth, crown jewels of Britain’s Cunard Steamship Lines, which were pressed into service as troopships in World War II. Overhauled and repainted in wartime gray, they logged more than a million nautical miles and carried more than a million British, Canadian, and American soldiers and airmen. Churchill believed that the two liners’ service shortened the war in Europe by as much as a year.

The saga of the “Warrior Queens”—also dubbed the “Gray Ghosts”—pounding back and forth across the Atlantic during their finest hours in 1939-1945, dodging German U-boats and bombers and setting speed records while helping to change the course of history, unfolds in this entertaining story. Briskly written and well documented, it sheds welcome light on an overlooked aspect of the war.

Butler shows that conversions in the United States made each of the two liners capable of ferrying as many as 16,000 troops during a single crossing, the equivalent of an army division. The Queens transported the ground crews and technicians who maintained the bombers and fighters of the mighty U.S. Eighth Air Force, the construction crews and ordnance personnel who set up the staging areas for the Normandy invasion, and the U.S. and Canadian infantry and armored divisions that would join the British in breaking into Nazi-occupied Europe on June 6, 1944. Earlier in the war, the two liners had ferried British and Commonwealth troops in the Middle East and the Far East.

Besides a million troops, says the author, the Queens carried half a million other war passengers, including statesmen, military and political leaders, dependents, prisoners of war, and thousands of British children evacuated to Canada.

Launched in 1934, the Queen Mary displaced 80,677 tons and had a top speed of 32.66 knots, while Queen Elizabeth, launched in 1938, displaced 83,673 tons and had a top speed of 32.2 knots.

This is a readable and revealing book.

Fleets of World War II by Richard Worth, Da Capo Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2002, 375 pp., photographs, notes, $35 hardcover.

Fleets of World War II by Richard Worth, Da Capo Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2002, 375 pp., photographs, notes, $35 hardcover.

For the benefit of naval buffs in general and World War II scholars in particular, award-winning historian and Naval Gazette contributor Richard Worth has produced a valuable reference work.

In an immensely detailed yet eminently concise volume, he analyzes the 63 countries that maintained navies, large and small, during World War II. He covers all the major combat vessels: battleships, aircraft carriers, cruisers, and destroyers, as well as the smaller frigates, destroyer-escorts, minesweepers, minelayers, and gunboats.

There is all the necessary information here on ship classes, tonnage, speed, and armaments, and much data about operations. Organized nation by nation, the volume is liberally illustrated and easy to use. The author also offers critical appraisals of both the ships and the navies they served. This is a first-class reference.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments