By Christopher Miskimon

On January 21, 1945, Lt. Col. Felix Sparks looked out over the rough, hilly terrain of the Vosges Mountains near Reipertswiller, France. Snow was falling, obscuring the shattered trees and shell craters, slowly covering the empty clips from M1 rifles strewn among thousands of spent brass cartridge cases. For the past four days, despite his best efforts, his battalion had been destroyed in these very hills. Six hundred of his men lay dead or wounded or were marching off to POW camps in Germany.

Sparks’s command, the 3rd Battalion, 157th Infantry Regiment, had enjoyed initial success in its advance just days earlier. Unfortunately, its success was not matched by the battalions on its flanks, causing the unit to become dangerously exposed and alone. Its opponents, the experienced 6th SS Mountain Division, seized the opportunity, and quickly the Americans were encircled. They fought bitterly until their ammunition was gone and the radio batteries drained from calls for artillery support.

Sparks’s command, the 3rd Battalion, 157th Infantry Regiment, had enjoyed initial success in its advance just days earlier. Unfortunately, its success was not matched by the battalions on its flanks, causing the unit to become dangerously exposed and alone. Its opponents, the experienced 6th SS Mountain Division, seized the opportunity, and quickly the Americans were encircled. They fought bitterly until their ammunition was gone and the radio batteries drained from calls for artillery support.

Sparks was outside the encirclement with the battalion staff and tried desperately to relieve the trapped GIs, personally leading rescue attempts. During one he crossed an open field to drag some of his wounded men to safety in full view of an SS machine-gun crew. He did it with no hope of survival, but the German troops were so impressed by such an act of selfless bravery they refused to kill him. In the end, it was all for naught; Sparks’s men could not break out and were forced to surrender. Years later, Sparks would lament, “My most tortured memory is of the Battle of Reipertswiller. It is still difficult for me to believe that it happened.”

Life in a World War II infantry regiment was an existence of horror and bravery, loss and comradeship, sacrifice and hardship. For those who led such units, the heavy psychological burden of command weighed upon them with each order given and each consequence of those decisions. Both officers and enlisted men suffered in their own ways even as they often performed acts of astounding courage. This duality is well captured in Alex Kershaw’s latest book, The Liberator: One World War II Soldier’s 500-day Odyssey from the Beaches of Sicily to the Gates of Dachau (Crown Publishing, New York, 2012, 433 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $28.00, hardcover).

The 157th Infantry was part of the 45th Infantry Division, the Thunderbirds. This division spent 511 days in combat during World War II, more than any other division. Originally a National Guard division formed by units from Oklahoma, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico, the 45th was in the heart of the fighting in Europe from July 1943 until war’s end. The original men, long-serving National Guardsmen who gave the unit a distinctive western flavor heavily accented by Native Americans, gradually disappeared as the crucible of combat ground them away. Only a handful remained through the war, a lucky few who were rewarded by watching their friends die or suffer wounds, to be succeeded by replacements from across America.

As they fought their way across Sicily to Italy, then on to Southern France and into the heart of the Third Reich, Felix Sparks went with them, leading them each step of the way. Sparks entered the regiment as a new second lieutenant in 1941. By 1945, he was a 27-year-old lieutenant colonel who had survived Salerno, Anzio, Reipertswiller, and a thousand other places only to arrive at the gates of the Dachau concentration camp outside Munich. There, he and his men confronted the full horror of the Nazi regime. The 45th Division newspaper would later proclaim, “Dachau Gives Answer to Why We Fought.” On April 29, 1945, Sparks and his men received a firsthand lesson, made only worse by an inquisitive reporter named Marguerite Higgins and a confrontation with a brigadier general from another division that would eventually lead to an encounter with General George S. Patton himself.

Kershaw goes on to describe how Sparks went on to a long career as a lawyer after the war. Remaining in the Colorado National Guard, he retired as a brigadier general. He was instrumental in organizing his old unit’s first reunions. Even so, with all this success, memories of the war never quite went away, and the author deftly reveals war’s lingering effects. The story of the 157th Infantry is expertly intertwined with that of Felix Sparks, a shared story that exemplifies the ability of soldiers to triumph under the brutal conditions of one of humanity’s worst moments.

Many adults reading this magazine will recall the multitude of World War II comic books available to them as children. Titles such as Fightin’ Army, GI Combat, Sgt. Rock, even the more arcane Weird War Tales regaled the young reader with stories of the war. The stories were generally fictional, set in the larger backdrop of the various theaters where American troops served. These comics entertained for decades-long runs but sadly are no more, leaving a young reader with no way to share these memories with their own families short of frequent trips to the comic book store.

Many adults reading this magazine will recall the multitude of World War II comic books available to them as children. Titles such as Fightin’ Army, GI Combat, Sgt. Rock, even the more arcane Weird War Tales regaled the young reader with stories of the war. The stories were generally fictional, set in the larger backdrop of the various theaters where American troops served. These comics entertained for decades-long runs but sadly are no more, leaving a young reader with no way to share these memories with their own families short of frequent trips to the comic book store.

Now there is a new way for adults and youths to read about history’s most famous battles. Zenith Press has released a new line of graphic novels (overgrown comic books to the old-fashioned) that tell factual, not fictional, war stories. Their newest release is Normandy: A Graphic History of D-Day (Written/Illustrated by Wayne Vansant, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2012, 103 pp., paperbound, $19.99). With its broad coverage of June 6, 1944, the book is an excellent way to introduce a young reader to the real stories of sacrifice, leadership, and heroism that made up the Normandy Campaign.

Beginning with the buildup to D-Day and carrying through to the liberation of Paris, the author tells his tale through a series of vignettes highlighting the notable events of the campaign. Chapters tell the stories of Omaha Beach, SS tank commander Michael Wittmann’s Tiger rampage, hedgerow combat, and Operation Cobra, to name a few. These chapters are designed to inspire curiosity and encourage further study. The illustrations are accurate without becoming overly graphic or bloody. Both the art and writing are clear and easy to understand. A fifth- or sixth-grader should have little trouble following the narrative; anything they do not understand only provides a chance for an impromptu history lesson. Middle schoolers are perhaps the perfect audience for this book.

If one is looking for a way to spread the love of military history to a younger loved one, this series is a good start.

The conflict in the Pacific was a war of incredible complexity. It encompassed an area from China to the West Coast of the United States, from Australia to the Aleutian Islands. Land, sea, and air forces had to be coordinated over these vast distances and deployed in decisive situations at just the right time. That the combatants were able to do this successfully is a minor miracle. Islands of Destiny: The Solomons Campaign and the Eclipse of the Rising Sun (John Prados, NAL Caliber, New York, 2012, 388 pp., index, photographs, maps, $26.95, hardcover) takes one campaign of that enormous struggle and shows how the disparate forces involved fought together in a mutually supporting effort in search of victory.

The conflict in the Pacific was a war of incredible complexity. It encompassed an area from China to the West Coast of the United States, from Australia to the Aleutian Islands. Land, sea, and air forces had to be coordinated over these vast distances and deployed in decisive situations at just the right time. That the combatants were able to do this successfully is a minor miracle. Islands of Destiny: The Solomons Campaign and the Eclipse of the Rising Sun (John Prados, NAL Caliber, New York, 2012, 388 pp., index, photographs, maps, $26.95, hardcover) takes one campaign of that enormous struggle and shows how the disparate forces involved fought together in a mutually supporting effort in search of victory.

The Solomons Campaign was fought across an island chain that was remote, mostly undeveloped, and in a location critical to each side’s war aims. Japanese control gave them the ability to interdict the link between the United States, Australia, and New Zealand and to threaten both of the latter with eventual attack. The Allies had to prevent this at any cost, and in mid-1942 they took steps to do so.

As the Japanese began building an airstrip on the island of Guadalcanal, the United States landed Marines to seize it. Successfully landing a force there required naval support. Navies could not act freely without air support overhead. Likewise, the Japanese response needed the same assets. Thus began a long struggle for control of the area, a battle that involved Marines and soldiers on the ground, sailors at sea, and pilots and aircrews in the skies above.

The struggle only ended after more than a year of hand-to-hand jungle combat, dogfights in the air, torpedo and bombing runs, battleship duels, and tense torpedo attacks by swift destroyers. Prados begins with the immediate aftermath of the Japanese defeat during the Battle of Midway and continues to the isolation of Rabaul and the fighting around New Georgia. Along the way he weaves a narrative that ties together the many separate elements involved in this pivotal campaign.

Adolf Hitler has rightly earned his place as one of history’s great villains. Volumes have been written about him in attempts to answer the many questions that arise from his reign as the leader of Nazi Germany. One such question, at once fascinating and controversial, is simply how this man swayed millions of people to follow him into one of humanity’s darkest episodes. Historian and documentary filmmaker Laurence Rees adds his own assessment to this body of knowledge in Hitler’s Charisma: Leading Millions into the Abyss (Pantheon Books, New York, 2012, 354 pp., index, photographs, maps, notes, $30.00, Hardcover).

Adolf Hitler has rightly earned his place as one of history’s great villains. Volumes have been written about him in attempts to answer the many questions that arise from his reign as the leader of Nazi Germany. One such question, at once fascinating and controversial, is simply how this man swayed millions of people to follow him into one of humanity’s darkest episodes. Historian and documentary filmmaker Laurence Rees adds his own assessment to this body of knowledge in Hitler’s Charisma: Leading Millions into the Abyss (Pantheon Books, New York, 2012, 354 pp., index, photographs, maps, notes, $30.00, Hardcover).

The book begins with a quote of Hitler’s: “My whole life can be summed up as this ceaseless effort of mine to persuade other people.” He was a complex character, full at once of flaws and abilities, dark ambitions paired with an inability to relate to normal people. Rees explores how Hitler was able to capitalize on the fears of the German people in their time of troubles in the late 1920s and early 1930s, how he could connect to their basic and basest needs. But there is more to Hitler than this. He also used fear, murder, torture, and coercion to get what he wanted. Not all who joined his ranks saw this charisma; some thought little of him but felt he was Germany’s best chance for a great rebirth. Others simply went along with the Nazis.

Also covered is Hitler’s ability to sway youth, something the Nazi apparatus put much effort into in the belief this would create lasting generations of dedicated followers. In essence, he created a nation ready to follow him anywhere. This confidence in their destiny and faith in their Führer led to horrible ruin, but it was also due to Hitler’s charisma that a nation was willing to go with him into infamy.

World War II finally proved the supremacy of modern mechanized warfare using the vast potential of the internal combustion engine to move and fight as never before. Naysayers who longed for the glorious days of cavalry were finally silenced as the futility of animal versus machine was decisively proven for all to see.

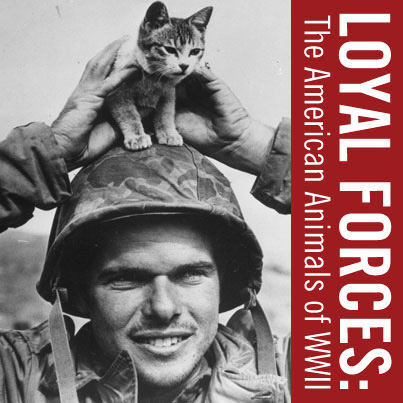

That is, for the most part. Despite the rise of vast formations of trucks and tanks and the steadily increasing capacities of aircraft, there were still a few places vehicles simply could not go. Further, there were jobs that machines were unable to perform. On occasion, the required machinery simply was not available. When that happened, humans resorted to their animals to do the lifting, scouting, and even fighting. The American military’s use of animals is documented in Loyal Forces: The American Animals of World War II (Toni M. Kiser and Lindsey F. Barnes, National World War II Museum and Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, 2013, 124 pp., illustrations, $35.00, hardcover).

That is, for the most part. Despite the rise of vast formations of trucks and tanks and the steadily increasing capacities of aircraft, there were still a few places vehicles simply could not go. Further, there were jobs that machines were unable to perform. On occasion, the required machinery simply was not available. When that happened, humans resorted to their animals to do the lifting, scouting, and even fighting. The American military’s use of animals is documented in Loyal Forces: The American Animals of World War II (Toni M. Kiser and Lindsey F. Barnes, National World War II Museum and Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, 2013, 124 pp., illustrations, $35.00, hardcover).

This photo essay shows the myriad ways in which animals were used by the military for working purposes and kept by soldiers as pets, providing a release from the stresses of service. The first animals taken in by the military were used as security for factories and other critical installations in the United States. Fear of sabotage ran high in the months after Pearl Harbor, and dogs were inducted into the services since guard dogs were already an accepted way of increasing physical security.

Before long, dogs were assigned other roles such as scouting, message bearing, pulling sleds, and even a stint at mine detecting, which ultimately proved a failure largely due to the training methods and attitudes of the Army, which failed to properly prepare the dogs for that role. Once in combat, many dogs performed heroically; a few, such as Chips, a dog with the 3rd Infantry Division who attacked and captured an Italian machine gun nest singlehandedly, even engaged the enemy.

Further chapters of the book cover other animals, including mules, horses, and carrier pigeons. Use of the mule in Italy and Burma is well documented. They were vital for carrying supplies in rugged, undeveloped terrain where even a jeep could not go. Often they evacuated casualties and the bodies of the fallen. True to their name, pack mules also toted the 75mm pack howitzer artillery piece on occasion, disassembled into six loads, one per mule.

Lesser known are the horses that took part in the last American cavalry charge, a desperate action against the Japanese in the Philippines in January 1942. The U.S. 26th Cavalry, many of its soldiers actually Filipinos, attacked a Japanese force that ambushed them at the village of Morong. While a success, the overall outcome in the Philippines was defeat. The animals who had charged the Japanese were themselves butchered by the starving Americans for their meat.

The final chapters are reserved for pictures of the various pets and mascots GIs adopted around the world, collected from a number of archives and private donors. These photographs put a more human face on those who served America in its great time of need. Each chapter contains brief descriptions of the animals’ uses and training along with examples of famous animals and their deeds.

The memoirs of World War II veterans are beyond counting at this point, but relatively few were written as diaries during the war and later published. Fighting With the Desert Rats (Major H.P. Samwell, presented by Martin Mace and John Grehan, Pen and Sword Publishing, Barnsley, UK, 2012, 214 pp., photographs, index, $39.95, hardcover) is one such, originally published after the author’s death in January 1945 and now reprinted in the original type.

The memoirs of World War II veterans are beyond counting at this point, but relatively few were written as diaries during the war and later published. Fighting With the Desert Rats (Major H.P. Samwell, presented by Martin Mace and John Grehan, Pen and Sword Publishing, Barnsley, UK, 2012, 214 pp., photographs, index, $39.95, hardcover) is one such, originally published after the author’s death in January 1945 and now reprinted in the original type.

Samwell joined the 7th Battalion Argyle and Sutherland Highlanders in 1938 as a second lieutenant. This was a Territorial (Reserve) unit and was activated in mid-1939 as war approached. In June 1942, the battalion embarked for Egypt as part of the 51st (Highland) Division attached to the Eighth Army. Seeing action at the Second Battle of El Alamein, Samwell was recognized for his bravery in leading his company after its commander was killed and he was wounded himself.

From there through the battle for Sicily, Samwell recounts the experiences of his unit as frontline soldiers, mixing descriptions of desperate close combat with hard-won breaks from the front. Like most at his level, Samwell could find the confusing orders of higher headquarters frustrating, and his description of fatigue duty at the docks in Tripoli will sound true to veterans of any army even today.

Marine Major Roger Broome died from wounds received on the island of Saipan on January 18, 1945, some six months after the fighting there ended. His daughter Kathleen never had the chance to know her father, but in time she grew to become a professor of history and author. The Measure of a Man: My Father, the Marine Corps, and Saipan (Kathleen Broome Williams, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2013, 184 pp., photographs, maps, notes, bibliography, index, $34.95, softcover) is her effort to know and understand a father whose own sacrifice took him from her many decades ago.

Marine Major Roger Broome died from wounds received on the island of Saipan on January 18, 1945, some six months after the fighting there ended. His daughter Kathleen never had the chance to know her father, but in time she grew to become a professor of history and author. The Measure of a Man: My Father, the Marine Corps, and Saipan (Kathleen Broome Williams, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2013, 184 pp., photographs, maps, notes, bibliography, index, $34.95, softcover) is her effort to know and understand a father whose own sacrifice took him from her many decades ago.

Using her experience as a historian, the author weaves together multiple sources to create a picture of Major Broome’s world. Her father’s letters home, interviews, and writings of other Saipan veterans are combined with the official records of the battle to showcase what it was like for the men who went ashore on that small Pacific island in 1944. The work focuses on the personal experiences of Kathleen and her family as America headed toward war and her reservist father was called to active duty. How the family dealt with the absence of a loved one at war is well detailed. Her father’s letters are widely quoted and paint a vivid picture of what he was experiencing—within the censor’s limits and the boundaries of what he was willing to reveal about war to those who worried for him.

Hit by rifle fire in the thigh, Major Broome was evacuated to Hawaii and then to the continental United States. Along the way infection set in, and the leg was amputated. Later, a kidney had to be removed. Through it all Broome maintained a positive attitude, but the medical knowledge of the day was insufficient to the task of saving him. However, his memory was saved by a daughter who cared enough to gather and tell the tale of a man she never really knew but loved nevertheless.

The threat posed by the German battleship Tirpitz had an effect far greater than the ship’s actual service. It was a ship the Nazis could ill afford to lose. The loss of prestige and combat power the small Kriegsmarine would suffer with her loss was bad enough, but the threat the great ship posed by her very existence drew vital British resources away from other efforts. Britain’s shipping was its lifeline, and the Royal Navy and Air Force had no real choice but to make every effort to destroy Tirpitz and end the threat.

The threat posed by the German battleship Tirpitz had an effect far greater than the ship’s actual service. It was a ship the Nazis could ill afford to lose. The loss of prestige and combat power the small Kriegsmarine would suffer with her loss was bad enough, but the threat the great ship posed by her very existence drew vital British resources away from other efforts. Britain’s shipping was its lifeline, and the Royal Navy and Air Force had no real choice but to make every effort to destroy Tirpitz and end the threat.

The Hunt for Hitler’s Warship (Patrick Bishop, Regnery History, Washington, D.C., 2013, 426 pp., photographs, drawings, maps, notes, index, 27.95, hardcover) sums up the effort to destroy Tirpitz, an effort that took years and some 36 separate operations from the sea and air. After a short period in Germany’s Baltic Fleet, the battleship went into the Atlantic to be based in Norway. She would serve the rest of her existence either in the frigid North Atlantic or the fjords of Norway’s coast, hiding from fevered British exertions to find her.

Those exertions were indeed extensive. The British commando raid on St. Nazaire, France, used an old destroyer as a huge bomb to destroy the dock there, the only one large enough to hold Tirpitz if she broke out to the Atlantic as her sister Bismarck had. Attacks on the ship herself began with aircraft, but when that proved ineffective, midget submarines were sent in September 1943. These heavily damaged Tirpitz, requiring lengthy repairs that lasted into April 1944.

Once it seemed the ship would sail again, more air attacks went in, causing further damage and necessitating more repair work. British intelligence, using Enigma decrypts and other sources, planned new attacks each time the Nazi behemoth appeared about to sail. Finally, Royal Air Force Avro Lancaster bombers dropped heavy “Tallboy” bombs on Tirpitz, now trapped in a fjord because of critical fuel shortages. Struck twice, the battleship capsized, ending the peril to Allied convoys. The author’s detailed work provides a fascinating read for naval history buffs.

The war on the Eastern Front was a grinding struggle of massive armies moving over fronts hundreds of miles wide. By autumn 1944, the Soviet juggernaut had pushed its way past its own borders into Hungary, where it sought to complete an offensive that would drive the hated Nazis completely out of the Balkans. Hungary had been a German ally until then, providing troops and fuel for Hitler’s war machine. The country had endured German occupation since an attempt to withdraw from the war failed in March 1944.

The war on the Eastern Front was a grinding struggle of massive armies moving over fronts hundreds of miles wide. By autumn 1944, the Soviet juggernaut had pushed its way past its own borders into Hungary, where it sought to complete an offensive that would drive the hated Nazis completely out of the Balkans. Hungary had been a German ally until then, providing troops and fuel for Hitler’s war machine. The country had endured German occupation since an attempt to withdraw from the war failed in March 1944.

The story of a part of this five-month battle is detailed in Take Budapest! The Struggle for Hungary, Autumn 1944 (Kamen Nevenkin, Spellmount, Stroud, UK, 2012, 288 pp., photographs, maps, appendices, notes, index, $24.95, softcover). The massive Soviet offensive began in October 1944 with a coup de main attempt to seize the Hungarian capital of Budapest. From there the fighting became an attritional struggle as both sides brutally smashed at each other. The massive casualties suffered could be borne by the Soviets, who had long since resolved to accept them in exchange for victory. The Nazis could not do so, and their losses combined with Hitler’s refusal to give ground willingly drew in reinforcements better used elsewhere, leaving the approaches to Berlin more vulnerable to the eventual Soviet offensive there.

This book’s strength is largely in the use of soldiers’ memoirs and a vast collection of data in its appendices. Unit strength, numbers of tanks available, and myriad other details are laid out in the nine appendices, which cover 65 pages, around a quarter of the book. This will be of great interest to readers who want an in-depth synopsis of the composition of units on both sides. One appendix even recounts the war crimes committed by each army. It is extensive coverage that is deserved for a large battle.

Osprey Publishing continues to publish entries in its Duel series, analyzing the fights between two famous weapons and their users, detailing strengths, weaknesses, and actual combat performance. Fw200 Condor vs. Atlantic Convoy 1941-43 (Robert Forczyk, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2013, 80 pp., photographs, illustrations, maps, index, $17.95, softcover) chronicles one of the lesser known fights—that of the Luftwaffe’s bombers against the British convoy defense system. Usually taking a back seat to the submarine war, this smaller part of the fight was nevertheless full of innovative tactics, equipment, and desperate efforts by pilots and sailors alike.

Osprey Publishing continues to publish entries in its Duel series, analyzing the fights between two famous weapons and their users, detailing strengths, weaknesses, and actual combat performance. Fw200 Condor vs. Atlantic Convoy 1941-43 (Robert Forczyk, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2013, 80 pp., photographs, illustrations, maps, index, $17.95, softcover) chronicles one of the lesser known fights—that of the Luftwaffe’s bombers against the British convoy defense system. Usually taking a back seat to the submarine war, this smaller part of the fight was nevertheless full of innovative tactics, equipment, and desperate efforts by pilots and sailors alike.

In the early years of the war, air coverage for convoys was practically nonexistent. What antiaircraft weapons were available were mostly reserved for major warships, and aircraft carriers could not be spared for escort duty. This gave the Luftwaffe a chance to inflict damage with little fear of loss in return. As the war progressed, however, new ideas such as catapult-launched fighters for merchant ships and the cheaper escort carrier plugged the gap the Fw200s enjoyed, effectively putting an end to their depredations. They had provided a small but useful adjunct to the U-boat but were swept away by growing Allied power.

Short Bursts

Kharkov 1942: The Wehrmacht Strikes Back (Robert Forczyk, Osprey, softcover, 96 pp., $21.95). This book chronicles one of the Red Army’s worst defeats of World War II. This prelude to Stalingrad pitted German and Soviet forces, both preparing for an offensive, against each other.

Kharkov 1942: The Wehrmacht Strikes Back (Robert Forczyk, Osprey, softcover, 96 pp., $21.95). This book chronicles one of the Red Army’s worst defeats of World War II. This prelude to Stalingrad pitted German and Soviet forces, both preparing for an offensive, against each other.

Between Giants: The Battle for the Baltics in World War II (Prit Buttar, Osprey, hardcover, 488 pp., $29.95). The German-Soviet struggle in Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia is described. The focus is on how the three Baltic states suffered during the brutal fighting on the Eastern Front. The Courland Pocket receives particular scrutiny.

Frozen in Time: An Epic Story of Survival and a Modern Quest for Lost Heroes of World War II (Mitchell Zuckoff, Harper, hardcover, 418 pp., $28.99). This is the story of the Herculean effort to save three aircrews lost in Greenland. This book chronicles the massive search and rescue missions undertaken for downed cargo and bomber aircraft ferrying to Britain.

Reign of Terror: The Budapest Memoirs of Valdemar Langlet 1944-1945 (Valdemar Langlet, translated by Graham Long, Skyhorse Publishing, New York, 2012, 187 pp., photographs, index, $24.95, hardcover). This is the story of a Swedish university professor and amateur diplomat who worked to save Hungary’s Jews from deportation to death camps late in World War II. He did so without official help, producing fake documents and meeting with officials.

Code Name Pauline (Pearl Witherington Cornioley, Chicago Review Press, Chicago, 2013, 162 pp., appendix, index, $19.95, softcover). Aimed at a young adult audience, this is a memoir of Pearl Witherington, a woman who joined the British covert Special Operations Executive and served in France as both an agent and Maquis leader.

We Die Alone: A WWII Epic of Escape and Endurance (David Howarth, Lyons Press, Guildford, CT, 2007, 232 pp., appendices, $16.95, softcover). Norwegian Commando Jan Baalsrud was the only survivor of a Nazi ambush. He led his pursuers through an artic wilderness and, against all odds, escaped and survived with the help of local Norwegians.

We Die Alone: A WWII Epic of Escape and Endurance (David Howarth, Lyons Press, Guildford, CT, 2007, 232 pp., appendices, $16.95, softcover). Norwegian Commando Jan Baalsrud was the only survivor of a Nazi ambush. He led his pursuers through an artic wilderness and, against all odds, escaped and survived with the help of local Norwegians.

The War Below: The Story of Three Submarines That Battled Japan (James Scott, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2013, 448 pp., Notes, Index, $28.00, hardcover). The submarine war in the Pacific was every bit as harrowing as the Battle of the Atlantic. Here the author picks three of the top American submarines of the war and reveals the experiences of their crews in the ultimately successful undersea war against Japan.

The Dodger: The Extraordinary Story of Churchill’s American Cousin, Two World Wars, and the Great Escape (Tim Carroll, Lyons Press, Guildford, CT, 2013, 318 pp., Illustrations, Notes, Index, $26.95, hardcover). John Bigelow Dodge, cousin by marriage to Winston Churchill, served in both world wars. During World War II, he was captured but repeatedly escaped, including one flight from Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

Priest, Politician, Collaborator: Josef Tizo and the Making of Fascist Slovakia (James Mace Ward, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, 2013, 362 pp., Illustrations, Notes, Index, $39.95, hardcover). This is a biography of Josef Tizo, a Catholic priest and Slovak nationalist whose desire to protect his nation led him into collaboration with the Nazis. As the war progressed he became a player in the Holocaust.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments