By Roy Morris Jr.

On the evening of August 7, 1937, two neophyte radio broadcasters went to dinner together at the luxurious Adlon Hotel in Berlin, Germany. Edward R. Murrow and William L. Shirer had never met before that night. Murrow, newly arrived in London as the European director for the Columbia Broadcasting System, was looking for an experienced reporter to cover the growing unrest on the Continent sparked by the bristling reemergence of Germany as a military power. In the unprepossessing, Chicago-born Shirer, Murrow had found just the man he was looking for, although other CBS executives did not know it at the time.

William Shirer: A Savvy Journalist

Murrow and Shirer were physical opposites: Murrow was tall, dark, handsome, and impeccably groomed; even his hair looked shellacked into place. Shirer was mid-sized, bespectacled, balding, and rumpled. He constantly smoked a pipe and gave off the air of a vaguely distracted English professor at a small Midwestern university. In both cases, looks were deceiving. Murrow was no mere pretty-boy broadcaster, as Shirer first thought, but a tenacious and instinctive newsman with a first-rate mind and a quick grasp of political realities. Shirer, for his part, was no airy academic, but a savvy professional journalist who had covered news events from Paris to Afghanistan for more than a decade. In the course of his career, he had written about such luminaries as Mahatma Gandhi, Charles Lindberg, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Isadora Duncan, and the glowering new strongman of Europe, Adolf Hitler. He spoke fluent French and German and could get by in Spanish and Italian.

Despite his background, Shirer was out of a job when Murrow asked to meet him. After five years as chief Berlin correspondent for William Randolph Hearst’s Universal Service, Shirer had been let go in a belt-tightening move by the company. With a pregnant wife and a dwindling bank account, he was preparing to return to the States to look for work in New York City when Murrow’s telegram arrived unexpectedly on his desk like a gift from the gods. At their meeting, Murrow offered Shirer a new job on the spot, at the same $125 a week he had earned with Universal Service.

Shirer accepted—he had little choice if he wanted to remain in Europe—and Murrow mentioned casually that he would have to do a voice test for the CBS brass before the job became official. A week later, in a makeshift Berlin studio, a nervous Shirer alternately squeaked and mumbled through a disastrous audition, made more difficult by the fact that he had to climb onto a packing crate in order to reach the microphone dangling seven feet in the air. CBS balked; Shirer sounded less like a broadcaster than a bookkeeper who had been caught with his hand in the company safe. Murrow stood firm—he needed Shirer’s mind and experience, he argued, not his voice. Eventually, the executives caved in. The most fortuitous and influential journalistic partnership of the era had begun.

Edward Murrow: “Director of Talks”

Murrow’s handling of the Shirer affair revealed his innate ability to identify talent, act quickly and decisively, and exert an irresistible but not overbearing charm on others to get his way. Born dirt-poor in rural North Carolina in 1907, Murrow moved with his family across the country to the Pacific Northwest, settling in the lumber town of Blanchard, Washington. The youngest of three boys, he excelled both academically and athletically, putting his six-foot-two-inch height to good use on the championship Edison High basketball team. Summers spent working as a lumberjack enabled the ambitious youth to save enough money to put himself through Washington State College in Pullman.

Once again Murrow excelled, getting elected student body president, starring in amateur theatricals, and attracting the attention of the school’s talented and formidable—if physically stunted—speech professor, Ida Lou Anderson. With the help of Anderson, who had been crippled by polio as a girl, Murrow honed his speaking skills to the point that he was twice elected president of the National Student Federation of America (NFSA). After graduation, he parlayed that position into a full-time job with the NSFA in New York City. His radio career (and lifelong CBS connection) began when he spearheaded the NSFA-sponsored “University of the Air,” an educational program that featured such celebrated guests as Albert Einstein, Mahatma Gandhi, German President Paul von Hindenburg, and British Prime Minister Ramsey MacDonald. This, in turn, led to Murrow’s hiring by CBS as “director of talks” in 1935.

Two years later, CBS executives decided to put out to pasture their chief European correspondent, Cesar Saerchinger, a music critic by trade whose greatest accomplishment as a journalist involved the live broadcast of a nightingale’s song in a Kentish garden. In April 1937, Murrow and his sophisticated wife, Janet, who could trace her ancestry back to the Mayflower, moved into an apartment at 84 Hallam Street in London, four blocks from Broadcasting House, the Art Deco-style headquarters of the British Broadcasting System.

The former Pacific Coast lumberjack settled easily into his new surroundings, buying his suits from expensive Savile Row tailors and immersing himself in English culture. He moved away from Saerchinger’s pretentious coverage of the Royal Family, fancy horse races, and promenades, and instead introduced the American public to colorful Cockneys from the East End docks, fiery speakers at Hyde Park, and pub-crawling dart throwers in Essex. At the same time, he was turned down for membership by the American Foreign Correspondents Association, who did not consider radio broadcasters legitimate newsmen. Murrow worked hard to change that perception.

Shirer’s First Scoop: Anschluss

It did not take long for his hiring of Shirer to pay dividends. In early March 1938, Shirer’s first scoop fell literally into his lap. Austrian-born Adolf Hitler had been demanding for months that his homeland become part of a greater Germany. When the Austrians scheduled a referendum to vote on the issue, Hitler strong-armed Austrian chancellor Kurt von Schuschnigg into canceling the vote, resigning from office, and, in effect, handing over his sovereign nation to the ungentle embrace of Nazi Germany. Shirer happened to be in Vienna at the time, arranging for a radio broadcast of a children’s choir, when the long-threatened Anschluss (annexation) of Austria began. The first inkling he had of the move was a shower of propaganda pamphlets dropped from circling airplanes. On the streets below, mobs of Swastika-wearing thugs paraded through the city, shouting “Sieg Heil! Sieg Heil!” and “Ein Reich, Ein Volk, Ein Führer.” Shirer knew immediately what it all meant.

Rushing to the office of the state-run radio, Shirer attempted to file an on-air report, but bayonet-wielding Nazis turned him away. He tried again two hours later—still no luck. In despair, he telephoned Murrow, who was on his own talent-scouting trip to Warsaw, Poland. Murrow advised Shirer to fly to London and broadcast his scoop from the CBS studio there. Meanwhile, Murrow chartered a Lufthansa flight—he was the only passenger on the 27-seat plane—and flew in to Vienna to cover Hitler’s expected triumphant arrival. The next night, March 13, 1938, at 8 pm, CBS made broadcasting history when Murrow, Shirer, and a quickly organized team of correspondents in Paris, Rome, and Berlin went on the air with the first-ever multilocation live broadcast, reporting on the Austrian Anschluss and the reaction to it in other European capitals.

Murrow had not intended to go on the air personally, but he could not find anyone else to appear on such short notice. Speaking in a clipped, staccato baritone that would quickly become his trademark, Murrow told listeners that Vienna was in a festive frame of mind. “Many people are in a holiday mood; they lift the right arm a little higher here than Berlin and the ‘Heil Hitler’ is said a little more loudly,” he reported. “Young storm troopers are riding about the streets, singing and tossing oranges out to the crowd.” It was the first radio broadcast of Murrow’s soon to be legendary career.

In Vienna, Murrow observed firsthand the growing power of the Nazis and what it meant for the Jewish residents of Austria and, by extension, the rest of Europe. He paced the streets restlessly as mobs smashed and looted Jewish stores, dragged men and women into the streets, and savagely beat anyone who attracted their malign attention. One night in a Viennese bar, he personally witnessed a young Jewish man cut his own throat with a razor. Returning to London, Murrow sounded a cautionary tone on the air. “It was called a bloodless conquest, and in some ways it was,” he told listeners. “But I’d like to be able to forget the haunted looks on the faces of those long lines of people outside the banks and travel offices. People trying to get away. I’d like to forget the tired futile look of the Austrian army officers, and the thud of hobnail boots and the crash of light tanks in the early hours of the morning in the Ringstrasse. I’d like to forget the sound of the smashing glass as the Jewish shop streets were raided, the hoots and jeers at those forced to scrub the sidewalk.”

“Hello, America. This is Berlin Calling.”

For the next few months, Murrow’s warnings seemed overly dire. After the Anschluss crisis faded from public consciousness, American radio listeners grew bored with the European status quo. Once again, CBS focused its broadcasts on such harmless pastimes as orchestra concerts, children’s choirs, and royal parades. Murrow and Shirer spent much of their time crisscrossing the Continent booking lightweight entertainment; the nightly news roundups were discontinued. When Shirer went to Prague in September 1938 to report on the impending crisis between Germany and Czechoslovakia over the disputed Sudetenland, a mountainous border province that was home to thousands of German-speaking Czechs. CBS executives made him promise to give up his five-minute broadcasts if there was not enough news to fill them out.

“My God,” Shirer remembered later. “Here was the old Continent on the brink of war— Hitler might start it within twenty-four hours, Prague might be wiped off the map overnight by the big bombers—and the network was most reluctant to provide five minutes a day from here to report it!”

Events would force the network to rethink its initial reluctance. Shuttling back and forth between Prague and Berlin, Shirer filed daily reports, beginning each one with a jaunty opening: “Hello, America. This is Berlin calling.” The greeting may have been jaunty, but the news was not. Emboldened by his grab of Austria, Hitler now insisted on great swaths of Czechoslovakia as well. Shirer observed the German Führer closely and saw what many others at the time did not: a morose, high-strung dictator who walked with a noticeable tic and sported dark circles under his eyes.

“This man is on the edge of a nervous breakdown,” Shirer confided to his diary. Hitler was playing a high-stakes game, but in the end it was British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain whose nerves gave out first. Shirer reported the series of meetings between Hitler and Chamberlain at the Rhine resort of Bad Godesberg, where local buildings were decorated with thousands of Swastikas and Union Jacks. “Mr. Chamberlain is a pretty popular figure around here,” he noted dryly.

For weeks, the world waited as Hitler upped his demands and threatened war. At CBS headquarters in New York, veteran announcer Hans von Kaltenborn, now going by the slightly less German-sounding name H.V. Kaltenborn, slept on a cot in the office and delivered some 102 broadcasts and news bulletins on the worsening situation. Murrow, in London, coordinated reports from the various European capitals, noting that in the English capital “trucks loaded with sandbags and gas masks were to be seen. The surface calm of London remains, but I think I notice a change in people’s faces. There seems to be a tight strained look about the eyes.”

“Peace in Our Time”

When Chamberlain returned to London from Munich after negotiating the sellout of Czechoslovakia, waving the infamous piece of paper above his head that guaranteed “peace in our time,” Murrow went to the Czech embassy to seek out his friend, Jan Masaryk, the foreign minister. Together, they sat all night waiting for a call from the British government that never came. “As I rose to leave,” Murrow recalled later, “the gray dawn pressed against the windows. Jan pointed to a big picture of Hitler and Mussolini that stood on the mantel and said: ‘Don’t worry, Ed. There will be dark days and many men will die, but there is a God and He will not let two such men rule Europe.’”

Winston Churchill, a leader of the opposition to Chamberlain in the House of Commons, was not so sure. Characterizing the agreement as “sordid, squalid, sub-human, and suicidal,” he told the prime minister: “You were given the choice between war and dishonor. You chose dishonor and you will have war.”

While the world waited for Germany’s next demands, Murrow returned to New York to discuss expanding his staff. He returned to London in the spring of 1939, having gotten network approval to add more correspondents to his team. First hired was Thomas Grandin, a Yale-educated academic with a wispy voice but a firm grasp of European politics. Murrow installed Grandin in Paris and tabbed Eric Sevareid, a 26-year-old, North Dakota-born reporter for the Paris Herald, as Grandin’s assistant.

Meanwhile, William Shirer continued broadcasting from an increasingly militant Berlin, where Hitler was beginning to make noises about annexing part of Poland to ensure German access to the Baltic Sea. Unlike Czechoslovakia, Poland had been assured by the British and French governments that they would come to Poland’s defense in the event the Nazis attacked, and Shirer correctly inferred that war was inevitable. In the midst of the darkening situation, CBS Vice President Paul White, a longtime foe of Murrow’s, ordered the European correspondents to produce a change-of-pace broadcast, “Europe Dances,” from various continental cabarets. Murrow, risking his job, refused outright. One week later, on September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland. World War II had begun. The question of dancing was suddenly moot.

A hasty decision by NBC and Mutual Broadcasting to suspend their European broadcasts left CBS with an open field. Murrow moved into the void, hiring additional staff to report from various capitals. Among those coming aboard that fall were Mary Marvin Breckinridge, an old college friend of Murrow’s who would become the first female national broadcaster; Cecil Brown, a journalist and former merchant mariner; Larry LeSueur of United Press; Winston Burdett of Harvard by way of the Brooklyn Eagle; Charles Collingwood, a Cornell alumnus; and Howard K. Smith, a champion hurdler from Tulane. They fanned out across the Continent while Shirer held down the fort in Berlin, harassed by no fewer than three Nazi censors before each broadcast. He got around the censors, to a degree, by using colloquial American phrases and an ironic tone in his voice. Sometimes he would simply quote directly from Hitler’s speeches, confident that the audience back home would read into them the same brutish posturing that Shirer did.

CBS President Willam Paley complained that Shirer was becoming too noticeably anti-Nazi in his broadcasts, but the journalist was unrepentant, then or later. “Nobody could have lived in that country as long as I and not have hated the Nazis,” he reasoned.

Covering the War in France

Throughout the winter and spring of 1939-1940, the so-called Phony War dragged on, with German, English, and French troops watching each other warily across France’s supposedly impregnable Maginot Line. That changed suddenly on May 10, 1940, when Germany launched a simultaneous invasion of France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. A new word, blitzkreig, was introduced to the world. Eric Sevareid, returning to Paris from Cambrai, heard German artillery and saw flashes of explosions like lightning in the distance. It was, he told listeners, “truly a lightning war, a war of sudden sounds and flashing machines. It comes and is gone before you can move, and the men you rarely see.”

Shirer, in Berlin, took a broader view. “The blow in the West has fallen,” he announced. “The battle which will decide the future of Germany for a thousand years caught everyone here completely by surprise.”

As the German Army rolled relentlessly toward Paris, Mary Marvin Breckinridge reported on the steady stream of refugees in the French countryside: “Baby carriages full of quilts, and bicycles with boxes tied all over them with bits of string. One little girl carried a black cat, and several families brought their dogs with them. One woman, who arrived alone and looked less tired than the rest, was questioned by a little group of people: ‘What happened to my town? Was my home bombed?’” Breckinridge, who was engaged to an American diplomat, soon left CBS to join her fiancé in Berlin, her place in journalism history—as the only girl among “Murrow’s boys” —assured. In London, Murrow described a somber mood. “I saw more grave solemn faces today than I have ever seen in London before,” he told listeners. “Fashionable tea rooms were almost deserted; the shops in Bond Street were doing very little business; people read their newspapers as they walked slowly down the streets. I saw one woman standing in line for a bus begin to cry, very quietly. She didn’t even bother to wipe the tears away.”

In Paris, Eric Sevareid drove up an eerily deserted Champs Elysees; normally bustling cafés sat empty, their wicker chairs turned upside down on tabletops. One final customer sat alone at his table finishing his wine, while a waiter, with true Parisian savoir faire, stood by patiently, towel over his arm. Sevareid barely made it out of town ahead of the Nazis in an endless line of escaping cars, trucks, and wagons. Refugees trudged along the roadside on foot, he reported, “like a stream of lava flowing past, the unstoppable river which came from the unimaginable eruption somewhere to the north.”

Larry LeSueur hitchhiked 150 miles from Belgium to Paris, then attempted to board an English troopship that was evacuating Nantes. Stopped literally on the gangplank—there was no more room—LeSueur turned and walked away. A few minutes later, a German dive- bomber dropped a bomb neatly down the ship’s smokestack, killing hundreds of soldiers. LeSueur shuddered at his near escape.

“Days of Pain and Mourning”

Shirer, to his immediate regret, accompanied the German Army when it entered Paris on June 17. Along the way he noted in his diary: “Verdun taken! Verdun, that cost the Germans six hundred thousand dead the last time they tried to take it. This time they take it in a day. What has happened to the French?” Coming into Paris with the victorious Nazis, Shirer recalled, “was no fun for me. As we drove down the familiar streets where I had spent the gold years of my mid-twenties (in the mid-twenties) I felt a gnawing ache in the pit of my stomach, and I wished I had not come. To make it worse, my German companions were in high spirits at the sight of the beautiful city.” The defiantly named Paris newspaper, La Victoire, carried the headline, “Days of Pain and Mourning,” and concluded its final editorial: “Vive Paris! Vive la France!”

More humiliation was coming for the French. Two days later, Shirer accompanied the Nazi high command into the countryside 45 miles north of Paris for a surrender ceremony orchestrated for maximum insult by Adolf Hitler. At Compiegne, the site of the German surrender in November 1918, German engineers tore down the museum wall housing the railway car in which the armistice had been signed. Hitler insisted that the same car, desk, and chair be used for the French surrender. Shirer observed Hitler with opera glasses through the train window.

“I have seen that face many times at the great moments of his life,” Shirer reported. “But today it is afire with scorn, anger, hate, revenge, triumph. He glances back at the monument, contemptuous, angry—angry, you almost feel, because he cannot wipe out the awful, provoking lettering with one sweep of his high Prussian boot.” Hitler did the next best thing; after the surrender ceremony, he had his troops dynamite the French memorial. The infamous railway car was dragged back to Berlin and put on public display. Ironically, it would be destroyed by Allied bombing later in the war.

The actual signing was slated to occur the next afternoon. Hitler had ordered all foreign correspondents back to Berlin, where he intended to announce his triumph to the waiting world, but somehow Shirer was overlooked. Within 90 minutes of the signing, his matter-of-fact account of the most humiliating French surrender in its history went out live via short-wave radio to New York and across the United States and Europe. Murrow, picking up the broadcast in London, immediately called newly installed British Prime Minister Winston Churchill with the news. Churchill, staying at his country home at Chequers, at first refused to believe it; his government had received no prior warning of the surrender, he said. But it was true. Shirer heard later, through confidential sources, that the German high command had allowed his surrender broadcast to go out over the airwaves unimpeded as a way to prevent Hitler from taking sole credit for the army’s extraordinary victory in France. Returning to Berlin, Shirer wondered if he would be arrested for his scoop.

The Battle of Britain Begins

England braced for immediate invasion. It didn’t come. Hitler, in a colossal misjudgment, postponed plans for a cross-Channel attack, opting for a more limited air war that bombastic Field Marshal Hermann Göring, chief of the Luftwaffe, assured him would quickly bring the British to their knees. For six weeks in the late summer of 1940, German pilots slugged it out in the skies over England with the remarkably young pilots, average age 21, of the Royal Air Force.

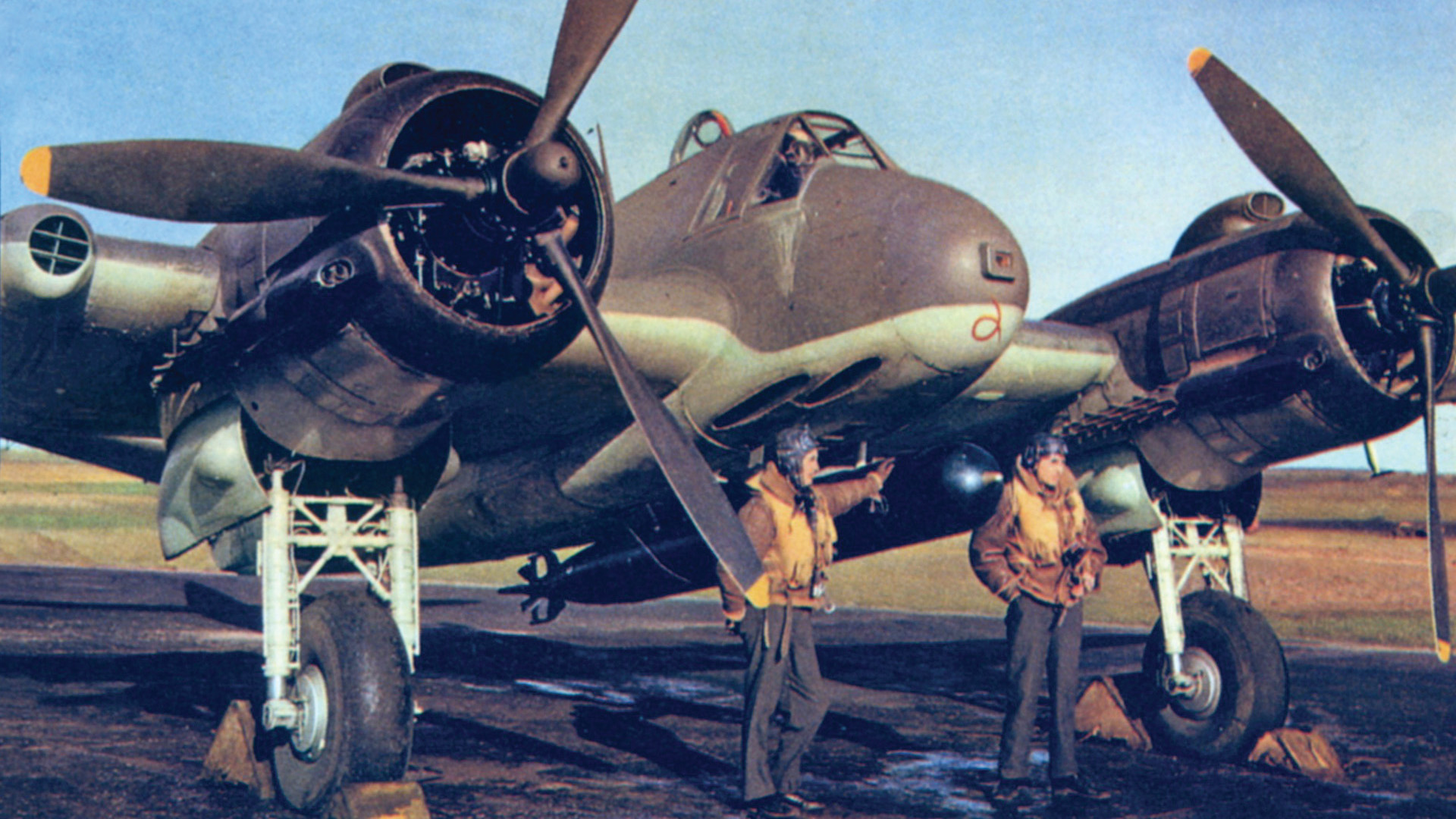

Despite staggering losses, the RAF held its own, helped immeasurably by a pioneering system of radar that could pick up enemy planes approaching from 150 miles away. Mainly, however, it was the sheer bravery and pluck of the young English pilots in their Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire fighters, who sometimes had to fly six sorties in one day. By the time Hitler called off the air war on September 17, they had saved the home island from invasion. “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few,” Winston Churchill said of the pilots, with eloquent simplicity.

The shining success of the British pilots (along with a perhaps misguided decision by Churchill to bomb Berlin) provoked Hitler to shift his attention from the pilots and their airfields to the British home front. Ed Murrow, who recently had begun a nightly broadcast, “London After Dark,” to describe the air war to American listeners, was as surprised as anyone when Nazi bombers began heading straight for London on September 7. That morning, a Saturday, he had driven out into the English countryside with two other journalists, Ben Robertson of PM, a left-wing New York newspaper, and Vincent Sheean of the North American News Alliance, to get a better vantage point of the fighting.

Parking his Sunbeam-Talbot convertible on a plateau overlooking the Thames estuary, Murrow and his friends walked to the edge of a turnip field to watch the smoke rising from two burning oil tankers set on fire by German raiders the night before. Suddenly, air raid sirens began wailing, and the newsmen looked up to see wave after wave of German bombers, flying in tight V-formations of 20 to 25 planes each, sweep up the river, headed for London. Diving behind a haystack to escape the shrapnel that had begun raining down on them like hail from British antiaircraft guns, they watched the endless procession of enemy planes in the skies over England. After 12 straight hours of bombing, the East End of London was in flames, 3,000 city dwellers were dead or injured, and Edward R. Murrow was about to become a legend.

“The Blitz”

Returning to London, he filed his first report of what immediately became known as “the Blitz” on September 8, from Studio B4 in the basement of Broadcasting House. “There are no words to describe the thing that is happening,” Murrow began. “A row of automobiles, with stretchers racked on the roofs like skis, standing outside of bombed buildings. A man pinned under wreckage where a broken gas main sears his arms and face. The courage of the people, the flash and roar of the guns rolling down streets, the stench of air-raid shelters in the poor districts.”

For the next 56 days, as Nazi bombers mercilessly pounded the city, Murrow patrolled the rubble-strewn streets, painting (as he said) “pictures in the air” for the American public. He chain-smoked three packs of Camels per day, drank endless cups of coffee, and got by on little or no sleep. On the advice of his old speech teacher, Ida Sue Anderson, he began each broadcast with his dramatic, half-second pause between his opening words: “This … is London.” It instantly became his catchphrase.

From the first, Murrow concentrated on the average British man and woman on the street. He sensed instinctively that Americans would identify with ordinary people who were undergoing an extraordinary trial. Avoiding the underground bomb shelters because he was afraid he would get too used to them Murrow and his favorite sidekick, daredevil CBS correspondent Larry LeSueur, sped down the blacked-out avenues of London in search of telling vignettes for the people back home.

“One becomes accustomed to rattling windows and the distant sound of bombs, and then there comes a silence that can be felt,” Murrow said. “You know the sound will return—you wait, and then it starts again. The waiting is bad. It gives you a chance to imagine things.” One night he found himself standing in front of a smashed grocery store. “I heard a dripping inside. It was the only sound in all London. Two cans of peaches had been drilled clean through by flying glass, and the juice was dripping down onto the floor.” Another time, he went to buy a hat. “My favorite shop had gone, blown to bits. The windows of my shoe store were blown out. I decided to have a haircut; the windows of the barbershop were gone, but the Italian barber was still doing business.” He went to buy batteries for his flashlight; the storekeeper told him he didn’t have to buy so many at once, they would be open all winter. “What if you aren’t here?” Murrow asked. “Of course we’ll be here,” the storekeeper replied. “We’ve been in business here for a hundred and fifty years.” On another occasion, he came upon a man sitting calmly at a desk in a pile of bombed-out rubble. “He was paying off the staff of the store—the store that stood there yesterday,” Murrow reported, noting signs he had seen that read stoically: “Shattered But Not Shuttered” and “Knocked But Not Locked.”

Bringing the Blitz to America

Murrow used every trick he could think of to bring the war into American living rooms. He broadcast from ground level, holding his microphone down to the street to catch the sound of bombs hitting the pavement or the unhurried footsteps of London residents walking—not running—to underground shelters. “The girls’ light, cheap dresses were strolling along the streets,” he reported admiringly. “There was no bravado, no loud voices, only a quiet acceptance of the situation. To me those people were incredibly brave and calm.”

One night he went onto the roof of Broadcasting House, where he broadcast under fire during a Nazi air raid. “The searchlights now are feeling almost directly overhead,” he recounted. “Now you’ll hear two bursts a little nearer in a moment. There they are! That hard, stony sound, that faint-red, angry snap of antiaircraft blasts against the steel-blue sky, the sound of guns off in the distance very faintly, like someone kicking a tub.”

He even found time to look in on a well-to-do Mayfair hotel, where he observed “many old dowagers and retired colonels settling back on the overstuffed settees in the lobby. It was not the sort of protection I’d seek from a direct hit from a half-ton bomb, but if you were a retired colonel and his lady, you might feel that the risk was worth it because you would at least be bombed with the right sort of people, and you could always get a drink.” Following the example of BBC reporters, he did not write out his scripts in advance, but merely dictated what he was seeing to his secretary, Kay Campbell, as it was going on. The effect was electric. This, indeed, was London during the Blitz.

Often, the bombs fell too close for comfort. One unexploded projectile, a hitherto unknown German airborne time bomb known as a UXB, flew through the seventh-floor window of Broadcasting House and crashed into the music library, where it lay inert for over an hour. Murrow was in the sub-basement at the time, and after the bomb exploded, killing or wounding four men and three women, he unflappably resumed his broadcast. Another night, Murrow and his wife were returning home from a broadcast; Ed wanted to stop in at the Devonshire Arms, a popular pub favored by reporters, but Janet persuaded him to keep walking. A moment later, “a tearing, whooshing shriek seemed to be coming down on top of them. They wrapped their arms around their heads to protect their eyes and ears. The blast flung them against the wall.” A bomb had landed directly on the pub, killing 30 people inside.

Berlin Diary

The Murrows’ apartment on Hallam Street became a de facto clubhouse for CBS broadcasters, rival journalists, political exiles, visiting Americans, and bombed-out friends. Czech foreign minister Jan Masaryk was a regular house guest.

While Murrow was riding out the Blitz in London, William Shirer continued broadcasting, albeit under heavy censorship, from Berlin. “We’re over here to try to get the truth if possible, a very difficult assignment these days,” he told listeners. Censors forbade him from using such words as “aggressive,” “militaristic” or “counterattack.” “Please remember it was Poland which attacked us first,” they said. One night they quibbled so long over his use of the word “reprisal” that he missed the broadcast altogether.

German officials telegraphed Shirer’s bosses in New York: “REGRET SHIRER ARRIVED TOO LATE TONIGHT TO BROADCAST.” Shirer complained bitterly, but executives urged him to stay on, “even if only reading official statements and newspaper texts.” This was too much for the proud newsman, who replied that he could hire a Nazi-American student for $50 a week “to read that crap.” After receiving word from a confidential source that the Nazis were building a trumped-up case against him as a spy, Shirer left Berlin for good in December 1940, smuggling out his private diaries in a stack of censor-stamped radio broadcasts. A few months later, safely in New York, he published Berlin Diary, an instant bestseller that afforded American readers their first close-hand view of Hitler, Göring, and their henchmen during their decade-long rise to power. It made Shirer famous, but it effectively ended his friendship with Murrow, who felt with some justice that Shirer had deserted the home team in the middle of the game.

“You Laid the Dead of London at Our Doors”

By then, the German bombing of London had subsided to sporadic, if still deadly, attacks. Murrow’s tireless broadcasts had become legendary, and no less an authority than Winston Churchill credited him with personally rallying American public opinion to the British side. Statistics bore out Churchill’s belief, revealing that only 16 percent of Americans had favored sending aid to Great Britain before the Blitz began, while the number had risen to 52 percent one month later. Returning to New York for a brief visit in November 1941, Murrow was feted by 1,100 well-wishers at a dinner at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. Poet Archibald MacLeish paid tribute to the broadcaster, telling Murrow: “You laid the dead of London at our doors, and we knew that the dead were our dead. You have destroyed the superstition that what is done beyond three thousand miles of water is not really done at all. There were some people in this country who did not want the people of America to hear the things you had to say.” Murrow received a standing ovation.

Without a doubt, Murrow’s reporting of the Blitz was the high point of his career, but he returned to London in the spring of 1942 with a new purpose in mind—to direct the news coverage of America’s recent entry into the war. His young staffers, including Larry LeSueur, Eric Sevareid, Richard C. Hottelet, and Cecil Brown, went into the field to report on the progress of the war, often at great personal risk. Brown was torpedoed aboard the British battlecruiser Repulse in the South China Sea, 50 miles north of Singapore, but used his experience as a merchant mariner to leap to safety and remain afloat for an hour before being fished out of the water by rescuers.

Sevareid parachuted out of a nose-diving C-46 cargo plane while flying “the Hump” over Burma and endured a harrowing 120-mile jungle trek to safety, helped by Burmese headhunters who were “some of the world’s most primitive killers.” Hottelet, a German-American from Brooklyn, was arrested in Berlin by Gestapo agents for espionage and held for several weeks before being exchanged for two Nazi spies in custody in the United States. Although proud of his ancestry, he understandably admitted that he “hated the Nazis’ goddamn guts.”

Murrow himself ventured into the field in March 1943 to cover the American campaign in Tunisia, code-named Operation Torch, where he came upon a knocked-out enemy tank in a stream bed. “Two dead [were] beside it, and two more digging a grave,” he reported. “A little farther along a German soldier sits smiling against a bank. He is covered with dust and he is dead. On the rising ground beyond a British lieutenant lies with his head on his arms as though shielding himself from the wind. He is dead too.”

Returning to London, Murrow was surprised and flattered to be offered the directorship of the British Broadcasting System. Prime Minister Winston Churchill was behind the offer; he considered Murrow nothing less than the voice of Anglo-American cooperation. Murrow gave the offer serious thought but opted in the end to remain at CBS.

“Orchestrated Hell”

Although saddened by the death of his young colleague Ben Robertson of PM, who had died in a plane crash in Lisbon Bay, Murrow lobbied to ride along with the Royal Air Force on a night bombing raid of Berlin. On December 2, 1943, he got his wish, climbing aboard a Lancaster bomber named somewhat prosaically D for Dog. His subsequent broadcast became a classic of wartime journalism, winning him the second of five Peabody Awards from the Overseas Press Club.

Entitled “Orchestrated Hell,” the account began in Murrow’s characteristic low key: “Last night some young men took me to Berlin.” It proceeded to paint an intense and sharply focused portrait of what it was like to fly through the pitch-black skies over the Nazi capital. “The small incendiaries were going down like a fistful of white rice thrown on a piece of black velvet. The cookies—the four-thousand-pound high explosives—were bursting below like great sunflowers gone mad. I looked down, and the white fires had turned red. They were beginning to merge and spread, just like butter does on a hot plate. It isn’t a pleasant kind of warfare. The job isn’t pleasant; it’s terribly tiring. Men die in the sky while others are roasted alive in their cellars. Berlin last night wasn’t a pretty sight. This was a calculated, remorseless campaign of destruction.”

Despite pleas from CBS executives to leave the flying to professionals, Murrow eventually made 25 sorties over Europe. Given the odds, he should have been killed—as was the pilot of his first mission, Jock Abercrombie, who went down in flames one month later. Airmen said later that Murrow’s presence on a mission was considered lucky.

The Sounds of Combat

Murrow reluctantly agreed to stay behind on D-Day, when the Allies launched their long-anticipated invasion of Europe. He was personally selected to read Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower’s order of the day announcing the invasion and concluding: “We will accept nothing less than full victory. Good luck. And let us beseech the blessing of almighty God upon this great and noble undertaking.” After that, he coordinated the confused first reports from CBS correspondents Larry LeSueur, Charles Collingwood, and Richard C. Hottelet, who came ashore at Utah Beach, and Bill Downs, who landed with British forces at Sword Beach.

Collingwood, lugging a 55-pound tape recorder, sent back the first eyewitness report to London: “The first craft onto the beaches was a little LCT. They came in doggedly looking very small and gallant with their heads up. Offshore several miles loomed the silhouettes of the big ships.” Although resistance was light, he continued, “This beach is still under considerable enemy gunfire. These boys are apparently having a pretty tough time in here on the beaches. It’s not very pleasant.”

After D-Day, the Allied forces drove steadily through France toward Nazi Germany. Murrow joined the others on the Continent after Paris was liberated on August 25, 1944. (Collingwood prematurely announced the liberation two days before it occurred, a journalistic catastrophe that would have resulted in his immediate firing if Murrow had not supported him and blamed the mistake, erroneously, as it turned out, on military authorities.) At Aachen, Germany, Hottelet got a more legitimate scoop, recording for the first time the actual sounds of combat. “Right down below us,” he reported, “the houses still are in German territory, and if anybody is leaning out of a bay window and draws a bead on this recorder, you will probably never hear it.” Distorted but jarring machine-gun fire punctuated his broadcast.

Buchenwald: Reporting on the Holocaust

Murrow hopped back and forth between London and the Continent as the Allies withstood the German surprise attack at the Battle of the Bulge and drove deeper into Germany, crossing the Rhine on March 24, 1945. He was with General George S. Patton’s Third Army when it liberated Buchenwald concentration camp, a few miles outside the city of Weimar, two weeks later. It was Murrow’s last scoop of the war and the most personally wrenching. Although he had been among the first newsmen to broadcast rumors of the Nazis’ infamous Final Solution more than two years earlier, nothing could have prepared him for the firsthand sights of the death camp itself.

“If you are at lunch, or if you have no appetite to hear what the Germans have done, now is a good time to switch off the radio, for I propose to tell you of Buchenwald,” he warned listeners on April 15. It had taken him three days to process the experience.

“There surged around me an evil-smelling horde,” he continued. “Men and boys reached to touch me; and they were in rags and the remnants of uniform. Death had already marked many of them, but they were smiling with their eyes.” He entered a prison barracks—“the stink was beyond all description”—and ran into the wraithlike former mayor of Prague, whom he did not recognize at first. “As I walked down to the end of the barracks, there was applause from the men too weak to get out of bed. It sounded like the hand clapping of babies. As we walked out into the courtyard, a man fell dead. Two others—they must have been over sixty—were crawling toward the latrine. I saw it but will not describe it.”

Inside a small garage, Murrow saw “two rows of bodies stacked up like cordwood. They were thin and very white. Some of the bodies were terribly bruised, though there seemed to be little flesh to bruise. Some had been shot through the head, but they bled very little. All except two were naked. I tried to count them as best as I could and arrived at the conclusion that all that was mortal of more than five hundred men and boys lay there in two neat piles.” He concluded his broadcast: “I have reported what I saw and heard, but only part of it. For most of it I have no words. If I’ve offended you by this rather mild account of Buchenwald, I’m not in the least bit sorry.”

He noted that many of the inmates had praised Franklin Roosevelt, who coincidentally died that same day at Warm Springs, Georgia. “To them the name ‘Roosevelt’ was a symbol, the code word for a lot of guys named ‘Joe’ who are somewhere out in the blue with the armor heading east. At Buchenwald they spoke of the president just before he died. If there is a better epitaph, history does not record it.”

Victory in Europe

Fittingly, Murrow was back in London for V-E Day, May 8, 1945. He reported several times, from various parts of the city, noting with his quick eye for detail that some of the people were strangely quiet. “They appear not to be part of the celebration,” he said. “Their minds must be filled with the memories of friends who died in the streets where they now walk.” He made his own pilgrimage down Hallam Street, where he remembered: “Your best friend was killed on the next corner. You pass a water tank and recall, almost with a start, that there used to be a pub, hit with a two-thousand-pounder one night, thirty people killed.” He closed reflectively: “Six years is a long time. I have observed today that people have very little to say. There are no words.”

Tapped by CBS President William Paley to head the postwar network back in New York, Murrow gave his last London broadcast on March 10, 1946. In it, he thanked the British people for their hospitality, courage, and commitment to democratic ideals. “They feared Nazism but did not choose to imitate it,” he said. “I am persuaded that the most important thing that happened in Britain was that this nation chose to win or lose this war under the established rules of parliamentary procedure [with] no retreat from the principles for which your ancestors fought.”

When he finished the broadcast, the BBC engineers in the studio presented him with the microphone he had used during the war, inscribed: “This microphone, taken from studio B4 of the Broadcasting House, London, is presented to Edward R. Murrow who used it there with such distinction for so many broadcasts to CBS New York during the war years 1939 to 1945.” In his hands, that microphone had been as much a weapon in the fight against Nazi tyranny as any rifle, pistol, or bayonet, and in the end, it had proved just as effective.

Edward R. Murrow went on to a distinguished career in the new medium of television. I have been a guest at the CBS Television Broadcast Center on W. 57th Street in New York City; his photo is proudly hanging in the entrance lobby.