By Phil Zimmer

The day’s flight was to be a fairly typical “rhubarb,” or a fast freelance strike, for the two pilots in their Bristol Beaufighters. It was to be a quick running attack on the Japanese airfield at Toungoo in Burma followed by impromptu strikes at anything they saw on the long trip back home over enemy-held territory to safety at Agartala. However, that February 13, 1943, mission was to be anything but routine for pilots Brian Hartness and Snowy Smith and their navigators.

They crossed the Irrawaddy River and then turned toward Toungoo. Spotting a Japanese supply train, they swooped down and attacked, leaving the crumpled locomotive in a cloud of escaping steam. When they got to the airfield, Hartness dived on an enemy bomber as it was taxiing into its dispersal, destroying it with a fierce burst of cannon fire. A second swing over the field enabled him to damage an enemy Nakajima Ki-43 Oscar fighter with his remaining .303-caliber bullets while dodging accurate Japanese flak and machine-gun fire.

Hartness was flying very low and momentarily took his eyes off the direct line of flight. To avoid the ground fire, he jinked the aircraft, but it was too late. His “Mighty Beau” struck a teak tree stump left standing after being stripped of its bark to season before being harvested.

“I hit the tree fair and square,” Hartness remembered. “It smashed in the leading edge of my starboard wing between the fuselage and the engine nacelle and severely dented the exhaust collector ring which formed the front cowling of the engine. By some miracle the propeller was undamaged.”

Hartness checked all the instruments and decided to make for safety at Ramu, located more than 300 miles to the northwest. There he gingerly landed his Beaufighter (No. EL286) to take on fuel and give the plane a good once over before flying on to his home base at Agartala, landing well after Snowy Smith’s plane had touched down.

Hartness got a good chewing out from his superiors over the damage to his aircraft and managed an offhand, low-key apology to the Scot corporal in charge of EL286’s ground crew. “Forget it,” came the reply, and turning to the other Scots the crew chief said: “There I told ye, our pilot will always come back!”

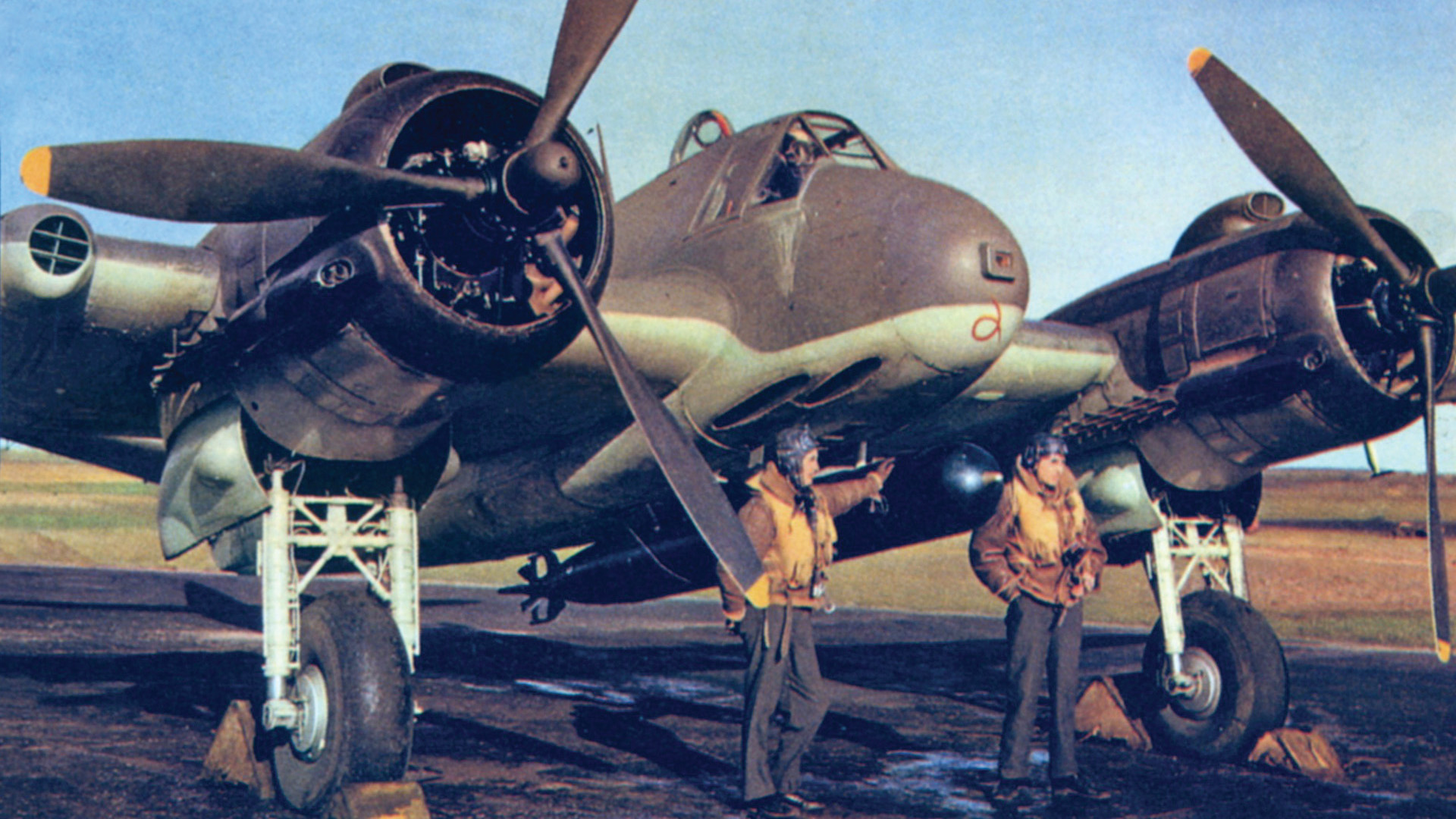

And many crews did come back, thanks in good part to the proven toughness of the Mighty Beau, which was the Royal Air Force’s first effective twin-engine strike fighter of World War II. The Bristol Beaufighter was a robust, pugnacious beauty of an airplane. It looked the role it played, that of a muscular, blunt-nosed pugilist that could take quite a beating while pounding the opposition to the ground. Although it lacked the svelte lines of the British de Havilland Mosquito, the tough Beau proved it could handle nearly anything thrown against it in all types of conditions, whether in the freezing fjords of Norway, the sun-baked expanses of North Africia, or the humid and unforgiving jungles of Burma.

The Beau traced its lineage back to the Bristol Beaufort, first envisioned in the mid-1930s as a torpedo bomber and a general reconnaissance bomber. The need for a stop-gap fighter was apparent, and the Bristol engineers looked for ways to adapt the Beaufort airframe for that role as well, saving crucial time and costs compared to developing an entirely new plane from scratch.

Designers Leslie Frise and Roy Faddon narrowed the fuselage, shortened the nose incorporating a single seat cockpit, added a dorsel position for a navigator/observer at midpoint on the fuselage, and added powerful but relatively quiet Hercules engines to the airframe. By utilizing the Beaufort’s existing wing, tail unit, and landing gear, they were able to produce the first prototype Beaufighter in just six months.

The Beaufighter made its maiden flight on July 17, 1939, just a few short weeks before Germany invaded Poland and ignited World War II. The plane was to go on to become the most effective land-based antishipping aircraft the RAF had for the first three years of the war.

Four 20mm cannons mounted in the lower forward fuselage were fitted to the first 50 production Beaufighters, although subsequent planes were standarized with six .303-caliber Browning machines guns added in the wings, two on the port side and four on the starboard. The later addition of rocket projectiles (RP) made the Beau’s punch even deadlier. The versatile plane was also modified to carry torpedoes and bombs.

The fact that the pilot was protected by armor plating and a bulletproof windscreen made the plane even more popular with most pilots. The pilot sat high and clear of the engines, providing an unobstructed view for low-level attack. The engines were set forward of the pilot, helping to protect the crew although the engine placement and power did give the plane a tendency to swing on take off and that caught a number of raw pilots by surprise. The swing could become uncontrollable if not immediately corrected, and sometimes resulted in crashes.

But it was the forward-placed engines, the plane’s overall ruggedness and versatility, and its four cannons acting occasionally as protective skids that helped win the pilots over.

“I have seen a Beau go through a copse of trees [scything them down], through the earthworks surrounding an ammunition hut, through the brick-built hut, and finished up literally just an armored box, with the pilot sustaining only a broken leg and his observer uninjured,” reported one veteran pilot.

Modifications were made as the plane evolved. Its tail was restructured, and instructions were provided in the attempt to overcome the plane’s swing on takeoff. Some later models were adapted to use the readily available inline Rolls Royce Merlin engine.

Some pilots remained skeptical. One noted that an American who had joined the RAF early in the war felt completely at home in a Beau “as he’d previously been a truck driver!”

Pilot Maurice Ball liked the ground-attack aircraft, which took the fight to the enemy and gave the craft high marks for its “front office,” or cockpit layout. Flying a Beau made him feel like a “knight of old,” really “achieving something” rather than waiting passively for the enemy to come to you.

The navigator/observer was perhaps the most underrated component of the Beaufighter. He had limited vision is his cupola located some 18 feet behind the pilot. He could see only two-thirds of the ground because of the craft’s nearly 58-foot wingspan, and often cloud cover, especially over Burma, would settle for weeks at a time. Perhaps the most challenging was the fact that the four 20mm cannons were placed in the body of the plane and they were not belt fed. That meant the navigator occasionally had to leave his position, either to unjam the cannon or arm wrestle fresh, heavy drums of 20mm shells into position, often while the plane was weaving to avoid enemy fire.

Not all the navigators were content to sit out an attack. Some toted along Thompson submachine guns on North Sea sweeps as something of an additional defense, although this meant smashing the navigator’s canopy before the gun could be used. Some later models incorporated Vickers or Browning machine guns and armor for the crucial second man.

The Beau was among the first of the multi-tasking planes of World War II. Its strong airframe proved readily adaptable to a wide range of weapons, and it was capable of carrying out a variety of missions against difficult targets and in deplorable weather conditions. It became one of the first land-based torpedo aircraft of the war and was instrumental in proving the operational capability of airborne interceptor radar, which was then in its infancy.

When the Luftwaffe increasingly turned from day to night bombing over Britain in the fall of 1940, the RAF turned to the Beaufighter as a night fighter. With Mark IV radar fitted to its nose and a radar scope in the observer’s position, the pilot was guided to the target by intercom directions. The craft proved capable in that role, and within six months the Beaufighters had used the temperamental radar to bring down more than a dozen Nazi planes. The number of enemy aircraft downed increased significantly as British radar and night fighting techniques improved.

The crews of the Beaus proved themselves to be masters of the night. Air Marshal W. Sholto Douglas noted in early April 1941 that although Beaufighters fitted with radar “carried out only 21 percent of the sorties at night, they have been responsible for 65 percent of the enemy aircraft destroyed.” He went on to strongly urge that steps be taken to substantially increase the supply of Beaufighters.

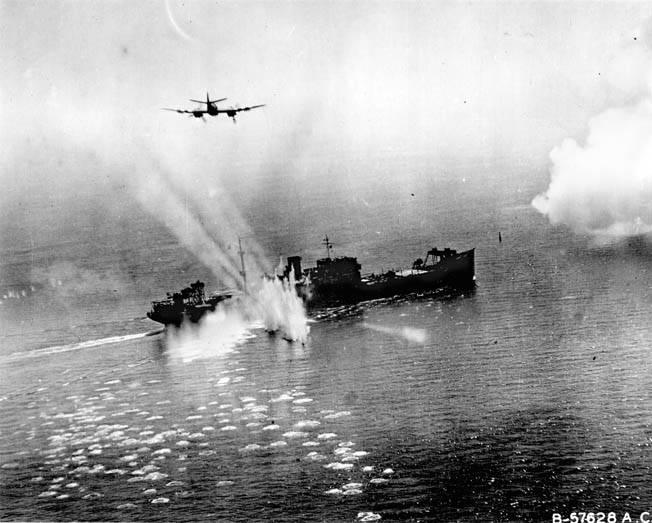

The RAF and Bristol also looked to the Beaufighter as a way to take the fight to the Germans, using it as a long-range fighter and attack aircraft to hit enemy bases and shipping as distant as Norway. The Beaus could cut a small craft in half and sink 800-ton vessels. Some observers said the Beaufighters were able to provide so much firepower in an attack “that the aircraft seemed to be halted in midair by the recoil.”

The firepower that a flight of Beaufighters could bring to bear was difficult to comprehend and even more difficult to overcome. On June 15, 1944, just a few days after D-Day, some 44 Beaus, including nine outfitted with torpedoes, took off from Langham, England, and linked up with nine North American P-51Mustangs serving as fighter cover.

They had received word that two large enemy ships and 17 escort vessels were at Dan Helder, north of Amsterdam, preparing to sail. The first wave of Beaus went in with their rockets firing and then opened with the cannons to make the ships’ gunners run for cover while the nine “Torbleaus” (or torpedo-equipped Beaus) came in to finish things off.

By the time they were done, the British had sunk two merchant vessels and one escort, seriously damaged six others, damaged four more, and left one escort calling for assistance. All the Beaus returned safely.

The Beaufighters also proved themselves in North Africa and the Middle East, handling a variety of roles from antishipping and bomber escort to low-level attacks on enemy transport and installations. They protected convoys from Tobruk and Malta and flew antisubmarine patrols over Royal Navy ships in the Mediterranean. The Beaus excelled in ground strafing missions against enemy road convoys. They would fly straight down the road at low altitude, letting loose with nearly everything they had. Then, the number two plane would fly down and repeat the process as the surviving enemy drivers looked on in awe from the ditches.

“Only on two occasions,” reports Wing Commander C.V. Ogden of No. 272 Squadron, “did aircraft actually scrape the road with their airscrew tips, but in each case the Beau returned safely.”

Although that comment might have been tongue in cheek, the strafing runs did test the fortitude of the pilots as well as the strength of the planes. A photo in the Imperial War Museum shows a Beau with 25-30 percent of its right wing clipped off after striking a telegraph pole at full speed while strafing a convoy on the Libyan coast. It flew another 400 miles and landed safely at its home base. Another photo shows the three-foot top of an armed trawler’s mast firmly imbedded in the nose of a low-flying Beau that made it back safely from a September 12, 1944, strafing run at Den Helder.

But it was in Burma and the Dutch East Indies that the plane really won over any remaining doubters and cemented its reputation as a tough, long-range plane capable of 1,500-mile missions that could take the fight to the enemy’s lair, consistently deliver damaging blows, and then bring the crew safely back. The planes and crews more than held their own in fighting over jungles and open ocean in fierce climatic conditions that made maintenance and supply exceptionally difficult.

It was in the Far East that the Beau picked up its British-given moniker of “Whispering Death” because the quiet, fast, and low-flying plane could often be on top of the enemy before he had time to react.

According to one wartime account, the Beaufighters brought “a new kind of war against the Japanese. It was aggressive war, war of attack, war of accurate destruction. Hirtherto he had been bombed by aircraft which flew at remote heights in the sky. Sometimes they were strafed by low-diving bombers. That kind of attack had given them time to take cover…. Now it was different. Aircraft which skimmed the trees hurtled through the steep valleys of Timor’s mountains, the hills screening the noise of their approach. They gave no signs of their coming and their guns’ fury destroyed everything it their path.”

Such an attack was perhaps best demonstrated by a Beaufighter pilot on a solo freelance sweep when he noted a full-dress ceremonial parade of Japanese at Myitkyina in northern Burma. The troops were celebrating Emperor Hirohito’s birthday and were drawn up in a square around the flagpole. The Beau made two passes, scattering mayhem and death among the gathered men and horses. The attack severed the flagpole, symbolically bringing the rising sun flag down over the bodies of the fallen color guard.

The Japanese resorted to a number of tactics to counter the Beaus and related Allied aircraft disrupting their supply lines in the effort to push them back from India and retake Burma. One simple expedient was the stringing of steel cables between two trees in the hope of snaring a fast, low-flying Allied plane. Such tactics had little impact, however, as the Allies continued their attacks and further weakened the already overstretched and overtaxed Japanese supply lines. RAF No. 27 Squadron alone managed to damage or destroy 66 locomotives between January and September 1943, along with more than 400 items of rolling stock.

As the last year of the war opened, the Japanese in Burma were pulling back in an attempt to avoid the oncoming British Fourteenth Army. The Japanese relied on riverboats, which opened them to additional attacks from long-range Beaus and Mosquitoes.

presents the aircraft’s distinctive profile with its large hump and dorsal machine-gun position.

Author Jerry Scutts noted, “Although it was far from unique in the Far East, the Beaufighter’s tough, conventional construction took it past its logical phase-out in preference to that of the superior Mosquito, which had an Achilles heel not previously revealed in more temperate climates.” The high levels of humidity and heat affected the bonding agents on the Mosquitoes’ wooden airframe, occasionally causing the craft to be grounded because of structural failure.

“In certain instances, therefore, the Beaufighter replaced its replacement,” added Scutts with a touch of irony.

In Burma, especially, he observed that the Beaufighter maintained its position as an exceptionally effective twin-engine strike fighter. Its unrivaled cannons and gun power—coupled with its rocket and torpedo capabilities—presented a challenge that the enemy simply could not match or counter.

The Mighty Beau lived on after the war, seeing continued years of service in the armed forces of countries ranging from Israel and Turkey to Portugal and the Dominican Republic. The Beau also lived on in the minds and hearts of the men it returned home safely in World War II.

Phil Zimmer is a U.S. Army veteran and a former newspaper reporter. He has written on a number of World War II topics.

Where did the “Beau” in the Bristol Beaufort bomber and its successor, the Beaufort fighter come from?

The closest plausible answer us that the Beaufort was named for the British hydrographer Adm. Beaufort, for whom the Beaufort Sea in the Arctic is named.

It’s also the name of a noble family in mediaeval England.

The Israeli Beaufighters were obtained in a clever subterfuge. Since the nascent Israeli air force was under a widespread arms embargo, obtaining planes was difficult. Six Beaus were rented for a war movie, but when they took off together for the first time, supposedly for filming, they kept on going, refueling in Italy and then on to Israel.

The Beaufighters saw some action in the 1948 war, but didn’t make much of a mark otherwise.