By Patrick J. Chaisson

On paper, the Reising submachine gun appeared to be an ideal close-combat weapon. Accurate, lightweight, and inexpensive to manufacture, it was selected by the U.S. Marine Corps in 1941 to arm its fighting men whose duties prevented them from carrying a rifle.

Once it went into battle, however, several design flaws became glaringly apparent. A poorly-designed ammunition magazine jammed frequently, while the firearm itself was prone to rust. The Reising’s sensitive internal mechanism proved impossible to keep clean in jungle environments; even a small amount of sand caught in its workings caused the gun to malfunction.

On Guadalcanal, disgusted Leathernecks traded this unreliable weapon for something more trustworthy at the earliest opportunity. According to legend, Lt. Col. Merritt A. “Red Mike” Edson even suggested his Marine Raiders toss the weapons into the Lunga River. Once so full of promise, the Reising instead distinguished itself as one of the worst small arms ever fielded by American forces.

Eugene G. Reising was a prolific and talented American ordnance engineer who could claim credit for 60 firearms related patents. In 1938, he began work on a select-fire weapon intended for sale to foreign military forces along with law enforcement agencies and private security firms at home. Reising’s design incorporated a number of innovations that resulted in an uncommonly accurate short-range shoulder arm.

Most submachine guns of the day employed an open-bolt action, a feature that helped prevent overheating but made aiming a challenge. The Reising’s delayed-blowback operating system used a closed bolt; when the trigger was pressed and a cartridge set off, the force of recoil cammed this heavy steel bolt down and rearward inside the receiver while compressing a stiff spring. The bolt then moved forward under spring pressure to chamber another round before locking back up into position.

Reising’s ingenious design enabled his firearm to deliver both precise aimed fire and an impressive cyclical rate of 550 rounds per minute. By sliding a switch on its receiver, the operator could select between full and semi-automatic modes or place his weapon on safe.

To keep it cool during rapid fire, the Reising had a series of radial fins machined into its 11-inch barrel. Early (First Design) barrels had 28 or 29 of these ridges, while later production models (Second Design) came with 14 cooling fins.

Many Reising barrels were fitted with a cylindrical metal compensator attached to the muzzle. This device deflected powder gasses upward through a series of slots, theoretically minimizing muzzle climb. Other controls included an aperture-style rear sight that could be adjusted from 50 to 300 yards and an action bar (cocking lever) concealed within the handguard.

The gun was chambered in U.S. standard .45-caliber, fed from a 20-round box magazine. It was 35.75 inches long and weighed 6.75 pounds empty. A carrying strap and loaded magazine increased that to 8.2 pounds. This new sub-gun also featured a full walnut buttstock—unusual for the time, as most similar European weapons tended toward all-metal construction.

In 1939, Eugene Reising met with officials from the Harrington & Richardson Arms Co. of Worcester, Massachusetts, to propose they build his “H&R Reising Submachine Gun M50” in return for a $2 royalty on each unit produced. The executives agreed and production commenced in 1940.

The leadership at Harrington & Richardson envisioned Reising’s innovative firearm competing for lucrative wartime contracts against the older M1928A1 Thompson. Compared with the Tommy Gun, their product promised lighter weight (8.2 lbs. versus 10.75 lbs.), increased accuracy due to its closed-bolt system, and less cost to manufacture. One Reising could be made for $50 ($977.90 in 2022) as opposed to $225.00 (over $4,400 today) for a military-issue M1928A1.

In July 1941, several Model 50 submachine guns were sent to Maryland’s Aberdeen Proving Grounds where they entered a series of U.S. Army field trials. The weapons failed to meet the Army’s expectations for performance in sand, mud, and dust, prompting H&R to make several hasty modifications. An improved version performed better in evaluations later that year, which led to an experimental order for some 1,000 M50s.

As the U.S. Army was committed to the development of an all-steel submachine gun that later became the M3 “Grease Gun,” it never formally adopted Reising’s firearm. Some historians believe the Army’s M50s were transferred to a quasi-military organization known as the Office of Strategic Services for use by guerillas and resistance groups overseas.

In November 1941, the U.S. Marine Corps also examined the Model 50 at their Quantico, Virginia, headquarters. Following a series of hurried tests, the Marines found it “acceptable when maintained to standards” —an observation that would come to haunt many Reising-armed Leathernecks in the Solomons less than a year later.

The Marines had fielded a small number of Thompsons in Central America and the Caribbean during the interwar years and appreciated it’s knockdown power at short range. Marine Corps senior leaders, anticipating a need for submachine guns in the approaching global conflict, declared that 100,000 of them would likely meet their wartime requirements.

These officials also knew that every M1928A1 Thompson then in production was earmarked either for the U.S. Army or a British contract. Whatever close combat weapon the USMC chose to provide for the thousands of tankers, junior officers, and signalmen now entering its ranks, it was not likely to be a Tommy Gun.

Another group of Leathernecks requiring a compact, but powerful, submachine gun were those men assigned to the 1st and 2nd Marine Parachute Battalions. When asked to adapt his M50 for these Paramarines, Reising produced a shortened M55 version.

The Model 55 had a pistol grip and folding wire stock. Its barrel was also half an inch shorter and lacked the M50’s muzzle compensator. The M55 measured 22.25 inches overall and weighed 6.2 pounds unloaded. Otherwise, the two variants were identical.

Designating the Reising a “limited standard weapon” in early 1942, the Marine Corps quickly let four production contracts with Harrington & Richardson Arms Co., who produced 55,000 wood-stocked M50s and folding-stock M55s for the USMC.

The first Reisings delivered to Marine combat units, so-called “commercial guns” assembled prior to Pearl Harbor, sported a high-gloss blued finish. Steel surfaces on later weapons were treated with an anti-corrosive phosphate coating known as “Parkerizing.” All Model 50s and Model 55s required extensive hand-fitting at the factory before they would function properly, a process that both slowed production and led to problems in the field.

The close manufacturing tolerances specified in H&R’s blueprints meant that bolts and other internal parts were not interchangeable. This required Reising-armed Leathernecks to take special care not to misplace or break anything when cleaning their sub-guns—no easy task in combat.

Marines training for war on bases across the U.S. soon discovered another unpleasant fact about this new gun: even a small amount of dirt in the receiver often stopped if from firing. It was another unintended result of the tight internal clearances called for in Eugene Reising’s design.

Yet the U.S. Marine Corps took pride in its troops’ proficiency with their individual weapons and resolved to make do with what was issued. When the 1st Marine Division (Reinforced) conducted a seaborne assault of Guadalcanal on August 7, 1942, some 4,200 of its men were armed with Reisings.

Additionally, senior sergeants and platoon commanders in Lt. Col. Merritt Edson’s 1st Marine Raider Battalion carried M50 submachine guns when they invaded the neighboring island of Tulagi that morning. One Raider, Marine Gunner Angus R. Goss, earned a Navy Cross and a mention in Richard Tregaskis’s classic book, Guadalcanal Diary, when on August 8 he single- handedly “hosed down” the occupants of a fortified cave with his Reising.

It was on Gavutu, a small but heavily-defended islet near Tulagi, that the Reising gun received its real baptism by fire. After coming ashore by landing barge at noon on August 7, the 1st Marine Parachute Battalion spent two bloody days trying to defeat 400 well-entrenched Japanese sailors belonging to the elite 3rd Kure Special Naval Landing Force. Before it was over, nearly 80 Paramarines would be dead or seriously wound.

Curiously, Marine Corps authorization documents required every Leatherneck in the 1st Parachute Battalion to be armed with an M55 Reising. Supply shortages, however, meant that plenty of Paramarines toted M1903 Springfield rifles on Gavutu. Nevertheless, the fighting there occurred mostly at short range and in heavily-jungled terrain— ideal conditions for a force primarily armed with submachine guns.

Yet the men of the 1st Parachute Battalion struggled to capture Gavutu. These novice Paramarines made their share of tactical errors, true, but also claimed their Model 55 sub-guns could not be depended upon to provide the firepower necessary to overwhelm a determined and dug-in foe. Reising-armed Marines on Tulagi and Guadalcanal also reported problems with their weapons’ reliability, an outcry that grew louder as the Solomons Islands campaign wore on.

The ever-present sand and grim of the battlefield continued to foul the Reising’s internal action and prevent its bolt from fully closing despite all efforts made to keep them clean. Its brittle firing pin broke easily and the poor-quality steel used to manufacture the receiver, barrel, and magazine rusted quickly in Guadalcanal’s humid climate.

The M55’s folding wire stock was especially despised. It often collapsed unintentionally and was too lightly constructed for service on jungle battlefields. Other operators complained about the Reising’s heavy eight-pound trigger pull and a defective safety mechanism that could cause a “slam-fire” if it was accidentally dropped.

Infuriated Marines reserved their worst criticisms for the double-stack, single-feed magazines. Called “the worst possible configuration for reliability” by one Leatherneck, this design malfunctioned after nearly every shot. Any amount of grit that collected inside the magazine, they learned, would almost certainly cause a stoppage.

An anonymous veteran of Guadalcanal said this about his Reising: “My last recollection of that weapon was that I flung it into the mouth of the Lunga River and to this day it’s probably still there.” Indeed, a perhaps-apocryphal story of the Solomons campaign credits Lt. Col. Edson with ordering his Raiders to dump their Reisings into the Lunga so they could obtain small arms that functioned properly.

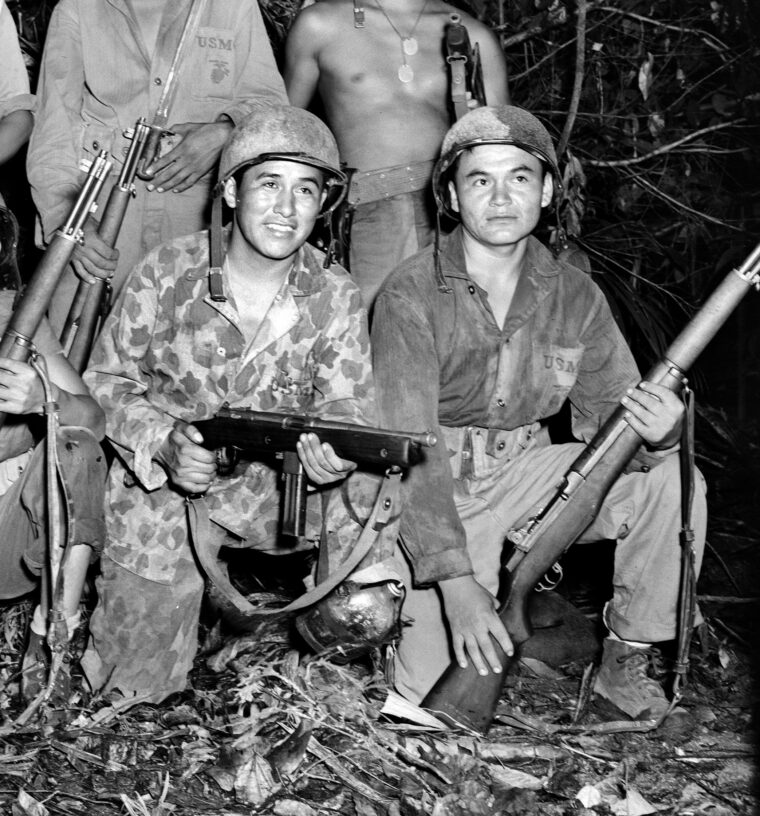

Photographs taken on Guadalcanal in late 1942 show only a few Marines still using Reising guns. As M1 Carbines and simplified M1 Thompsons reached the combat zone, surviving M50s and M55s were rapidly taken out of service. By early 1943, the USMC had canceled all production contracts for these troublesome sub-guns and restricted their issue to stateside commands.

While the Marine Corps had a poor experience with the Reising, this did not mean it was wholly unsuited for military service. During World War II, thousands of U.S. Coast Guardsmen patrolled lonely shorelines along the nation’s Atlantic, Pacific, and Gulf coasts. To arm the Coast Guard’s Beach Patrol, Harrington & Richardson initiated an additional run of 20,500 Model 50 submachine guns in July 1942.

Engineers at H&R also invented a single-stack magazine that solved the old design’s tendency to jam. Holding just 12 rounds, this device was inadequate for Pacific battlefields but helped give many a Beach Patrol member added confidence as he walked alone at night along a deserted stretch of sand.

Foreign governments also used Reising guns. The Soviet Union received 6,000 pieces as part of Lend Lease, with 2,000 reaching British and Commonwealth forces. The French purchased 4,000 M50 submachine guns in 1941 for shipment to Indochina; it remains unknown what happened to those firearms after Japanese troops occupied the region later that year.

To arm watchmen protecting America’s defense resources, Harrington & Richardson produced a weapon it marketed as the Reising Model 60 Semi-Automatic Rifle. This firearm differed from the Model 50 submachine gun in that it had an uncompensated 18.5-inch barrel and an action that fired one round for each press of the trigger. Beginning in 1942, the U.S. Defense Security Corporation procured several thousand M60s for use by agencies in charge of guarding factories, bridges, and other critical infrastructure. The Marine Corps obtained some Model 60 semi-auto rifles as well, reserving them for local protection details and interior guard missions.

After the war, H&R continued to manufacture small quantities of semi-automatic Reisings for civilian law enforcement organizations and private security firms. Many former USMC and USCG Model 50s also found their way into the gun lockers of police departments and correctional facilities. Others were given to a number of Central and South American governments as part of various foreign military assistance programs.

The last 2,000 Reisings to be manufactured, most of which were M60 rifles destined for Latin America, left Harrington & Richardson’s factory floor in 1960. Total production of all variants exceeded 120,000 units.

The Reising sun was an accurate, lightweight and—when kept clean—reliable shoulder weapon. These virtues did not excuse its dismal combat record. Overly complicated and difficult to maintain, this firearm should never have been accepted for front-line duty with the U.S. Marine Corps. The Reising’s intolerance for dirt, humidity, and rough treatment, together with a poorly designed and manufactured ammunition magazine, forever relegated it to the ranks of World War II’s least successful small arms.

Frequent contributor Patrick J. Chaisson writes from his home in Scotia, New York. The author wishes to thank Mr. Jonathan Bernstein, Arms & Armament Curator with the National Museum of the United States Marine Corps, for his assistance in the preparation of this article.

Join The Conversation

Comments