By John W. Osborn, Jr.

Though neutral for most of it, few countries had such a Passage through World War II as did Bulgaria.

That way was marked—or scarred—by brutality, treachery, a rumored royal death, one of the war’s least-known and most tragic intelligence disasters, and cynical power-playing as the country’s fate was discussed over doodling on a piece of paper.

Yet there was also one of the few successes in saving lives. And for the Bulgarians the ordeal did not finish with the war’s end—it was only beginning, with an ironic sequel after its conclusion.

“Boris is by temperament a fox rather than a wolf, and would expose himself to great danger only with the utmost reluctance” Hitler said about Bulgaria’s King Boris III before the monarch’s sudden, suspicious death. In fairness, Boris had seen his father forced from the throne for being on the losing side in World War I, then had to struggle for survival in a poisonous political atmosphere, brutal even by Balkan standards.

One unlucky prime minister’s head was returned to his family in a biscuit tin. Boris himself outran assassins through the woods on a hunting trip, commandeering a bus and driving it away while the panicked passengers ducked under their seats as shots shattered the windows. A 1934 coup by quasi-Fascist officers threatened to reduce his royal status to princely puppet until he staged his own in October 1935, and established a dictatorship. Yet, if the King was finally in complete control of events inside Bulgaria, he soon found that forces on the outside would shape his country’s future.

Hitler needed to cross Bulgarian territory to attack Greece and did not hesitate to use Germany’s 70 percent stranglehold on Bulgaria’s trade to force Boris to sign his de facto alliance, the Tripartite Pact, on March 1, 1941. But while Bulgaria permitted passage for the Wehrmacht to assault Greece it did not take part, then refused to join in the invasion of Russia, instead making—for the moment—a harmless gesture of declaring war against the United States and Great Britain on December 13,1941. And for a time it seemed that Bulgaria was, uniquely among Hitler’s hostage allies, getting the better of the deal with the devil.

Prices increased for its exports, and the Bulgarians were permitted, while having no part in winning them, to seize eastern Thrace from Greece and western Macedonia from Yugoslavia. “The Fuhrer is showing himself remarkably liberal towards Bulgaria,” Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels recorded in his diary on March 28, 1942, the likely lone time he would ever describe Hitler as such. The Fuhrer was back to his usual self a year later, meeting with Boris at his Wolf’s Lair headquarters in East Prussia to demand that Bulgaria finally declare war on Russia and hand over the country’s 50,000 Jews. With Boris refusing, the result was a shouting match between the Fuhrer and the sovereign.

“He had staked everything on ‘our Fuhrer,’ and now he was compelled to realize his card had been trumped,” Hitler’s personal pilot, Hans Bauer, observed while flying the beleaguered Bulgarian monarch home. But how Boris would continue to bluff was never to be known.

“I wished that we would be shot down by some enemy plane, so that it would be all over with me,” Boris glumly remarked on his return. While at his retreat in the Rila Mountains two weeks later, Boris rode up into the mountains and climbed to the top of the nearly 10,000-foot Musala Peak, something he’d done many times. Three days afterward, complaining of trouble breathing and chest pains, King Boris collapsed. Hitler rushed specialists to Bulgaria’s capital, Sofia, but four days later, inside his palace, at 4:22 p.m. on August 28, 1943, King Boris III died.

Though he was just 49, coronary thrombosis was announced as the cause and blamed on the mountain climb. But one of the German doctors reported to Berlin privately something sinisterly different, “…a Balkan death.” The king’s lower extremities suspiciously had blackened after he died. “The Fuhrer told me that it must be regarded as certain that King Boris was poisoned,” Goebbels declared in his diary. “Who mixed the poison isn’t known yet.”

Nor would it ever be. Although his widow would say two decades later, “My husband did not die a natural death,” she had refused an autopsy at the time. Since the new King, Simeon II, was only six, a three-member regency headed by his uncle took charge but a power vacuum had been created into which British intelligence was prepared to step in, with tragic, disastrous results.

“Our policy towards Bulgaria at present in the very nature of things must be fluid and opportunist. We are therefore in a position to wait on events and exploit any turn they may take,” replied the British Foreign Office in its Whitehall way of saying both everything and nothing when asked for advice by the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in January 1943. To the SOE, the King’s death eight months later provided the event to exploit—and there appeared to be the means to do so with.

Back in July 1942, the Bulgarian Communist Party, on orders from Moscow, had deceptively duped other groups opposed to the alliance with Hitler to form the Fatherland Front, which embarked on a campaign of arson, assassination, sabotage, and guerrilla resistance in the mountains. To make common cause, as it had with Tito’s Partisans in Yugoslavia, the SOE parachuted Mission Mulligatawny, Major Mostyn Davies and four enlisted men, into Albania on September 20, 1943.

Davies made an epic 84-day trek, mostly at night, across the steepest, 6,000 feet average, mountain range in the Balkans, and twice escaped encirclement by the Bulgarian Army to finally make contact with the Front. Regrettably, it would turn out that his powers of endurance were not matched by those for observation. His prewar career as a civil servant concerned with, among other obscure things, accounts for lighthouses, proved to leave Davies ill-equipped for ruthless, duplicitous Communists with loyalty to Moscow, not Sofia.

Davies naively accepted assurances from the Front that it was democratic and numbered 12,000 fighters. Actually, the Communists were in complete control, and the Front had scarcely 2,000 in arms and just 200 fighters where Davies happened to be. Instead of ordering Davies out, as the SOE would likely have done had it known the truth, SOE leaders perilously proceeded to deepen the disaster coming for it in Bulgaria.

A second mission, Claridges, just Major Frank Thompson and a radio operator, landed by parachute in Yugoslavia on January 25, 1944. An SOE agent with Tito’s Partisans, Major John Henniker, accompanied Thompson into Bulgaria to also meet with the Fatherland Front.

Thompson didn’t like what he saw. “I was glad they were not my prop and stay—a pretty inexperienced and low-level mixture of individual deserters from the towns,” he reflected to Davies’ brother. “Compared to the Yugoslav army they had an unreal and slightly horror-comic air of a brigand army, boastful, mercurial, temperamental, and an inexperienced yen to go it alone.”

Compared to the disciplined Partisans of Yugoslavia the Bulgarians shambled through the countryside under the watchful eyes of ever-present informers, without food and guides, with the SOE missions just an hour by truck from Sofia. Henniker returned to his own mission in Yugoslavia just in time—the Bulgarian Army launched 12,000 troops against the fumbling Front, trapping the Mulligatawny and Claridges missions.

Davies disappeared, and how he met his end is unknown. Thompson, for the moment, survived when a Bulgarian bullet struck the dictionary in his backpack as he was fleeing from an ambush—but it proved only a reprieve. Thompson was captured and executed by firing squad on June 5, 1944. The radio operator was the only survivor of the two missions.

“Your son’s life was not thrown away uselessly,” the SOE later tried to console Davies’ parents. “It is certainly true that the Partisan effort in Yugoslavia has been more spectacular in its results, and has indeed produced much more actual activity against the Germans, but the Bulgarian Partisan was not a forlorn hope, and your son’s task was not a hopeless one.”

What would be the SOE’s official excuse of an explanation for its covert calamity? “One thing above all hampered it—bad weather. For bad weather meant no arms; no arms meant no partisan fighting force and no fighting force meant no achievement against the German or Bulgar forces. One thing is abundantly clear that given arms, under the inspiring leadership of Major Davies, the Mission would have been capable of liberating territory inside Bulgaria and thus providing a base for future SOE operations. The failure of the Mission to do this is the story of man against the Gods of the Heavens.”

Just three months after Thompson’s execution, in the first nine bewildering days of September 1944, Bulgaria’s course in the war, and for the next half-century, was to be set. Sofia by then was being bombed by the Allies, and the economy was collapsing. With the Russians in control of Romania across the border, a new government in Sofia broke the Tripartite Pact, began peace talks with the Allies through its foreign minister in Turkey, and offered to form a coalition with the Fatherland Front.

Earlier, in Moscow, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had jarringly jotted down a proposed division of influence in the Balkans with Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin. Churchill was willing initially to concede 75 percent influence in Bulgaria to the Soviets, but Stalin demanded and received 100 percent.

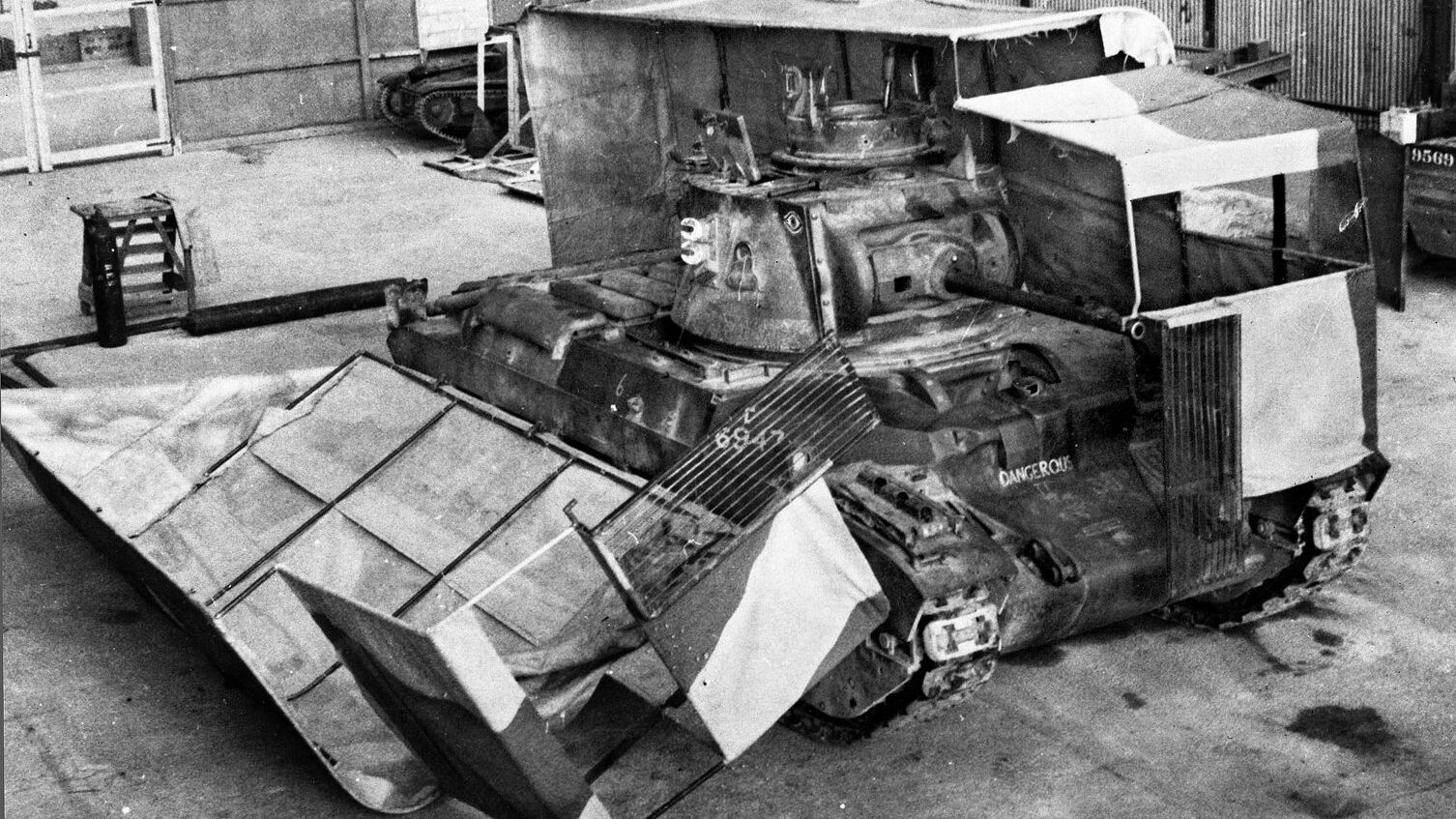

To forestall the peace moves with the West, Stalin declared war, and the Red Army swept into Sofia as Bulgarians lined the roads to applaud the movement of Soviet tanks and troops. The Fatherland Front, now numbering 9,000, seized control of more than 150 towns and villages; in Sofia itself, Army conspirators broke into a meeting of the Regency Council to arrest its members and bloodlessly occupied ministries and other key positions around the city.

A new government was formed, officially a coalition but with the Communists in effective control, and a month later the government sent a delegation to Moscow to sign an armistice. In successfully severing its ties with Hitler, Bulgaria was, along with Finland, one of just two nations allied with the Nazis to save their Jewish populations. King Boris III was once recognized as Righteous Among the Nations by Israel but later lost the designation amid charges that he permitted the deportation of 11,343 Jews in occupied Macedonia to the Germans. His defenders argued that the deportees were never Bulgarian nationals and that the Germans were in effective control in Macedonia at the time.

The Bulgarian Army, 450,000 strong, finally joined the war and fought alongside the Russians through Yugoslavia, Hungary, and eventually into Austria. But the Russians were soon waging a different war—a war on the Bulgarians themselves. Some 40,000 were imprisoned or executed. The child King, Simeon II, was allowed to leave unharmed, but it would be the Soviets’ sole act of mercy.

The three Regents were marched, naked, to a firing squad on February 2, 1945. A score of former ministers met the same fate. “You are ruling by sheer terror,” the former Fatherland Front dupe Nikolai Petrov now protested, and he got a deadly demonstration. Petrov was brazenly arrested at his seat in Parliament and hanged after a spectacular show trial spectacular in September 1947. With Petrov’s end completing the Communist takeover of Bulgaria, their new leader bluntly, brutally, warned any remaining opposition, “Reflect on your own actions, lest you suffer the same fate.”

An American journalist told a Bulgarian official he was moving on to Yugoslavia. The official was shocked. “Why, that place is a dictatorship!” he said.

Bulgaria would remain a bleak, brutal Communist nation until 1990. Afterward, in a remarkable twist even for the bizarre Balkans, none other than former King Simeon II would serve as the country’s democratically elected prime minister from 2001 to 2005, though he had never renounced his title or claim to the Bulgarian throne.

Author John W. Osborn, Jr., is a resident of Laguna Niguel, California. He has written for WWII History on a variety of topics.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments