By Lt. Col. Harold E. Raugh, Jr., Ph.D., U.S. Army (Ret.)

German Army Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg is regarded as a towering hero of World War I, the victor of the Battles of Tannenberg (1914) and the Masurian Lakes (1914 and 1915), as well as army chief of staff and master strategist. Called out of retirement, he became president of the Weimar Republic in 1925 and seemingly worked to preserve order in the midst of economic and social chaos and potential civil war.

Hindenburg’s tremendous popularity both during and after World War I generally obscured a darker, more Machiavellian side of his personality, the dictatorial actions he had taken that failed to achieve wartime victory, and his self-serving attempts to repudiate responsibility for Germany’s catastrophic defeat. William J. Astore and Dennis Showalter, in this finely crafted and felicitously written biography, Hindenburg: Icon of German Militarism (Potomac Books,: Washington, D.C.,: 2005, 133 pp., chronology, illustrations, maps, notes, bibliographic note, index, $12.95, softcover), have authoritatively chronicled Hindenburg’s military campaigns. More importantly, they have also conducted a fair and balanced assessment of his military and political career and his role in facilitating the rise of Hitler and the destruction of Germany.

Hindenburg’s tremendous popularity both during and after World War I generally obscured a darker, more Machiavellian side of his personality, the dictatorial actions he had taken that failed to achieve wartime victory, and his self-serving attempts to repudiate responsibility for Germany’s catastrophic defeat. William J. Astore and Dennis Showalter, in this finely crafted and felicitously written biography, Hindenburg: Icon of German Militarism (Potomac Books,: Washington, D.C.,: 2005, 133 pp., chronology, illustrations, maps, notes, bibliographic note, index, $12.95, softcover), have authoritatively chronicled Hindenburg’s military campaigns. More importantly, they have also conducted a fair and balanced assessment of his military and political career and his role in facilitating the rise of Hitler and the destruction of Germany.

This insightful book is divided into five chapters, paralleling the most important periods of Hindenburg’s life. Chapter 1, “Prewar,” traces Hindenburg’s life from his birth in 1847, to his commissioning in the Prussian Army in 1865 and service in the Austro-Prussian War (1866) and Franco-Prussian War (1870). He served in positions of increasing responsibility, was appointed to the imperial general staff, and retired as a general in 1911.

Upon the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Hindenburg was recalled to active duty and appointed commander of the Eighth Army on the Eastern Front. Hindenburg and his chief of staff, General Erich Ludendorff, made a superb command team. Utilizing the strategic mobility provided by their rail and road networks, the Germans crushed the overextended Russian forces at Tannenberg in August 1914. After further inspiring victories at the Masurian Lakes in 1914 and 1915, Hindenburg (as shown in Chapter 2, “The Eastern Front, 1914-1916”) became the indispensable hero and “the savior of the fatherland.”

After the German Army suffered appalling losses at Verdun and on the Somme during the first half of 1916, Hindenburg was appointed chief of the general staff in August. Hindenburg, assisted by Ludendorff, worked indefatigably to revitalize German war efforts, largely through economic and industrial mobilization. They disregarded the will of the Reichstag, the people, and the value of diplomacy, however, when they formed the “Third Supreme Council,” a virtual military-industrial dictatorship (as chronicled in Chapter 3, “Supreme Command, 1916-1917”).

By the beginning of 1918, czarist Russia had collapsed, but Germany’s earlier policy of unrestricted submarine warfare and other factors had brought the United States into the war on the Allied side. Germany still had the opportunity to negotiate a favorable conclusion to the war, but the reinvigoration of the German Army, combined with hubris at the highest levels, caused undue optimism. The Germans launched Operation Michael (Chapter 4, “Collapse and Catastrophe, 1918”), an attempt to overwhelm the British and French forces before the full weight of the American Expeditionary Forces arrived in Europe and tipped the scale in favor of the Allies in March 1918. After stunning initial successes, the German onslaught was halted. Hindenburg launched the German war machine in further offensives, but they were blunted, and the Allies counterattacked.

With the tide of victory turning against the Germans, Hindenburg and Ludendorff were quick to restore the civilian government and shift to it responsibility for the German defeat, which came with the Armistice on November 11, 1918. Hindenburg promoted the “stab-in-the-back” myth, which absolved the military leaders of responsibility and maliciously and falsely blamed “Bolsheviks, war profiteers, Jews, and other ‘November criminals’ on the home front for the Second Reich’s collapse.” Hindenburg became president in 1925, and to maintain order and prevent the spread of Communism, he sought (as traced in Chapter 5, “Weimar and Hitler”) the assistance of the Nationalist Socialists—he Nazis—thus legitimizing the party and paving the way for Adolf Hitler’s rise to power.

Astore and Showalter, in this compelling and well-researched biography, have ably cut through the layers of mythology that have grown around Hindenburg’s legacy and have presented a factual and objective assessment of his military and political achievements. The inescapable conclusion is that “Hindenburg’s reputation is irredeemably stained by the role he played in facilitating Hitler’s legal acquisition of power” and the advent of the second worldwide conflagration of 1939-1945.

Recent and Recommended

The First Crusade, A New History, by Thomas Asbridge, Oxford University Press, New York, 2004, 408 pp., illustrations, maps, glossary, chronology, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover.

The First Crusade, A New History, by Thomas Asbridge, Oxford University Press, New York, 2004, 408 pp., illustrations, maps, glossary, chronology, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover.

Thomas Asbridge, a lecturer in early medieval history at the University of London, is a recognized authority on the history of the Crusades. The First Crusade, the topic of this superb study, was instigated in 1095 by Pope Urban II, who exhorted Christians to “take up arms and prosecute a vengeful campaign of reconquest, a holy war that would cleanse its participants of sin.” Amazingly, a polyglot 100,000-man force responded to the pope’s speech and embarked on a 3,000-kilometer, three-year journey through treacherous lands and with meager supplies to “recapture Jerusalem from Islam in the name of the Christian god.”

Asbridge chronicles in fine prose the trek of the Crusaders to the Middle East and their battles with Muslim forces, notably at Antioch and finally at the siege of Jerusalem. Against all odds, the Crusaders captured Jerusalem in July 1099. In the name of God, the Crusaders butchered Jerusalem’s Muslim defenders until they “were wading up to their ankles in enemy blood.” The First Crusade, as demonstrated by Asbridge, spawned “deep-seated animosity and enduring enmity” between Christians and Muslims that continues to this day.

In Brief

Swords Against the Senate: The Rise of the Roman Army and the Fall of the Republic, by Erik Hildinger, Da Capo Press, Cambridge, MA, 2003, 240 pp., notes, bibliography, index, $18.95, softcover.

The devastating defeat suffered by the Romans at the Battle of Arausio in 105 bc set the stage for the rise of Caius Marius, the further professionalization of the Roman army, and eventual war. The backdrop for many of these events was the tension between Roman aristocrats and commoners and the demise of the Roman militia concept. The plebians forced the Roman senate to flout the law by permitting Marius to serve as consul twice within ten years. While a good general, Marius was not an able politician or statesman. His rule inflamed class strife and led to the Social War, 91-88 bc, in which poorly disciplined Roman forces did not perform well. Marius reformed the army, which was increasingly used as a domestic tool by various leaders and factions. Erik Hildinger writes authoritatively about the Roman army during this period, and of Marius’s replacement by Sulla, “who in turn spawned the man who transformed turmoil into imperial triumph, Julius Caesar.”

Sailors in the Holy Land: The 1848 American Expedition to the Dead Sea and the Search for Sodom and Gomorrah, by Andrew C.S. Jampoler, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2005, 312 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, notes, selected bibliography, index, $32.95, hardcover.

Sailors in the Holy Land: The 1848 American Expedition to the Dead Sea and the Search for Sodom and Gomorrah, by Andrew C.S. Jampoler, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2005, 312 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, notes, selected bibliography, index, $32.95, hardcover.

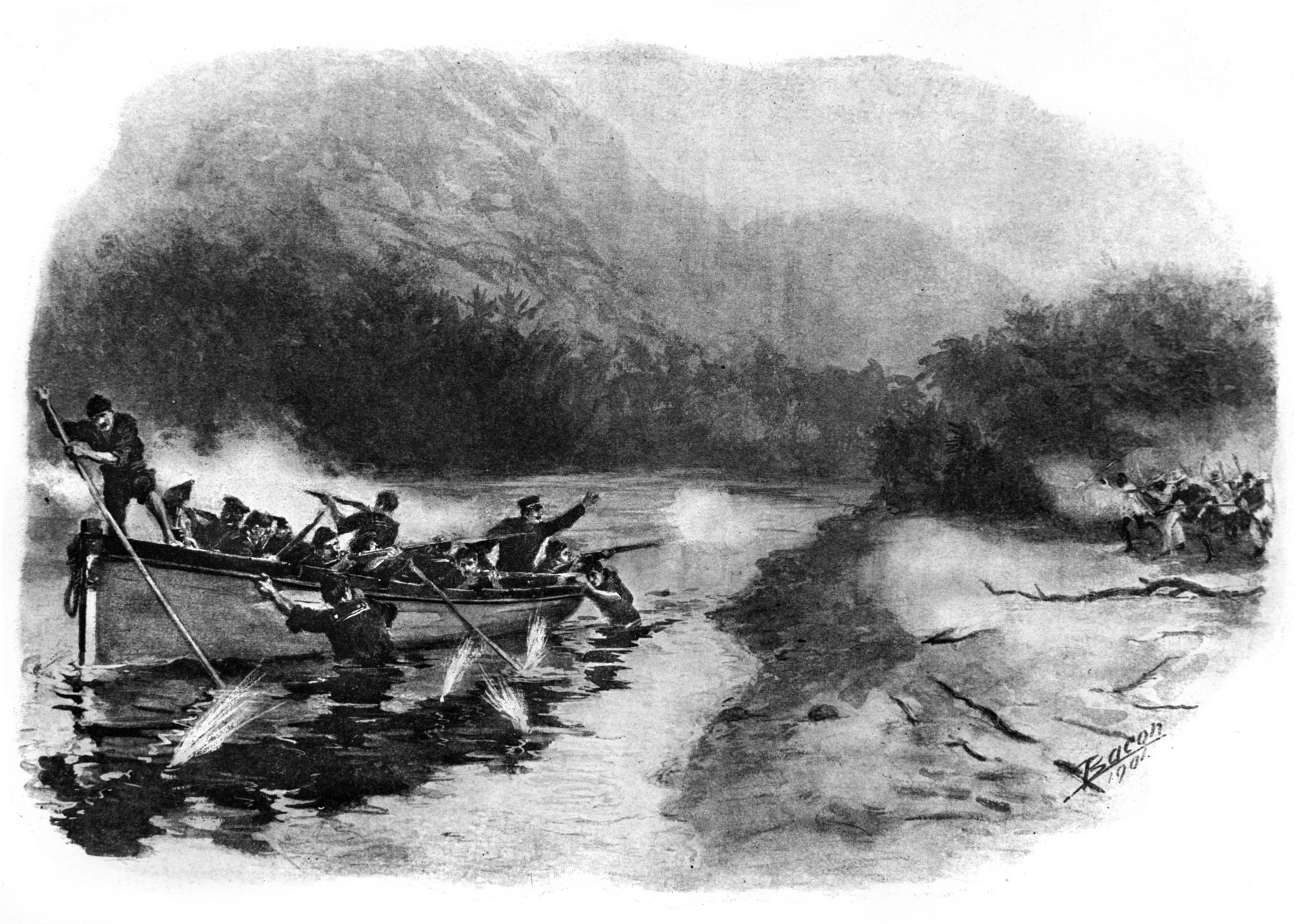

U.S. Navy Lieuenant William Lynch was an ambitious and adventurous man. In 1847, with the end of the Mexican War in sight, Lynch requested to lead a naval expedition “to circumnavigate Lake Asphalties or Dead Sea, and its entire coast.” While the stated goal of the expedition was scientific in nature—to ascertain the elevation of the Dead Sea—there was also an unofficial religious aspect to it. The deeply religious Lynch may have also been interested in locating the Biblical sites of Sodom and Gomorrah. Perhaps surprisingly, Lynch’s unusual request was approved. He was given command of the 250-ton USSS (U.S. Store Ship) Supply with a crew of 67 officers and men and supplies for a year. The ship departed New York in December 1847, bound for Acre in the eastern Mediterranean. The expedition reached the Sea of Galilee in April 1848 and traversed the Jordan River until it reached the Dead Sea—calculated by Lynch to be 1,234.589 feet below sea level. After an arduous but exotic adventure, Lynch’s expedition returned to the United States. in late 1848. Andrew C.A. Jampoler has chronicled this seminal expedition in compelling detail.

Civil War Sites, Memorials, Museums and Library Collections: A State-by-State Guidebook to Places Open to the Public, by Doug Gelbert, McFarland, Jefferson, NC, 2005, 208 pp., appendix, index, $35.00, softcover.

Civil War Sites, Memorials, Museums and Library Collections: A State-by-State Guidebook to Places Open to the Public, by Doug Gelbert, McFarland, Jefferson, NC, 2005, 208 pp., appendix, index, $35.00, softcover.

This readable and easy-to-use book lists and describes, arranged alphabetically by state, over 1,500 Civil War sites, memorials, and collections in the United States. “Sites” are defined as “the location of actual military action during the war,” while “monuments,” frequently on battlefields and related venues, commemorate military engagements, key leaders, and other historically important places, people, and events. “Collections” include “museums with permanent Civil War displays and libraries with significant collections pertaining to the war.” Entries, from the Davis Monument in Auburn, Ala., to the Abraham Lincoln Memorial Monument in Laramie, Wyo., generally contain capsule descriptions, directions, addresses and phone numbers, opening hours, and other user-friendly information. This work is equally valuable as a reference book and as a research tool.

“The Supply for Tomorrow Must Not Fail”: The Civil War of Captain Simon Perkins, Jr., a Union Quartermaster, by Lenette S. Taylor, Kent State University Press, Kent, OH, 2004, 264 pp., illustration, map, appendix, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover.

History books are full of the exploits and successes of combat commanders, but the quartermasters and logisticians, whose contributions to battlefield victory are indispensable, are frequently overlooked. Captain Simon Perkins, Jr., was a Union quartermaster during the Civil War who fell into the latter category—until the publication of this fine book. Perkins, after having served a 90-day enlistment in 1861, was commissioned a quartermaster captain in early 1862. For the following two and a half years, Perkins served in responsible logistical positions, including “officer in charge of forage on the Tennessee River; depot quartermaster at Stevenson, Alabama; headquarters quartermaster for Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans; charge of railroad transportation and quarters at Nashville, Tennessee; depot quartermaster and disbursing officer at Nashville; and depot quartermaster at Gallipolis, Ohio.” Lenette S. Taylor has done a fine job in chronicling Perkins’ military career, emphasizing his quartermaster responsibilities, a task made easier by the discovery and use of eight crates containing more than 20,000 documents that Perkins had saved after the Civil War. This outstanding biography deserves a wide readership.

Stonewall Jackson and Religious Faith in Military Command, by Kenneth E. Hall, McFarland, Jefferson, NC, 2005, 256 pp., illustrations, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00, softcover.

Stonewall Jackson and Religious Faith in Military Command, by Kenneth E. Hall, McFarland, Jefferson, NC, 2005, 256 pp., illustrations, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00, softcover.

“As any student of society knows,” claims Professor Kenneth E. Hall, “men and women have made war over religion, and religion about war, for millennia.” Many military leaders, in what may seem paradoxical, have had strong religious beliefs, frequently suggesting eccentricity. Hall focuses on Confederate Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, his religious convictions, and his military achievements. Jackson could be viewed as a “priestly warrior,” believing in a just war and the “Lost Cause” he was fighting and willing to be martyred for. Hall also explores the Protestant and Catholic roots of religious faith in military command, as personified by Protestants Oliver Cromwell, Gustavus Adolphus, Henry Havelock, and Charles G. Gordon, and Catholic warriors El Cid, Emperor Charles V, and King Philip II. In this intriguing study, Hall provides a provocative view of military leadership and religious conviction in which “nationalism or patriotic fervor and religious faith work side by side.”

Redcoats and Zulus: Selected Essays from the Journal of the Anglo Zulu War Historical Society, compiled and edited by Adrian Greaves, Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley, UK, 2004, 224 pp., glossary, maps, illustrations, index, $39.95, hardcover.

Redcoats and Zulus: Selected Essays from the Journal of the Anglo Zulu War Historical Society, compiled and edited by Adrian Greaves, Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley, UK, 2004, 224 pp., glossary, maps, illustrations, index, $39.95, hardcover.

The 1879 Zulu War, pitting red-coated Soldiers of the Queen against fearless spear-wielding Africans continues to fascinate military historians. The 25 educational and entertaining Zulu War-related essays in this fine anthology have been culled from the Journal of the Anglo Zulu War Historical Society, formed in 1997. Highlighting new source materials and modern research methods, articles cover the causes of the conflict; disease, illness, and life on campaign with the British Army in South Africa; individual battles, personalities, and weapons; and the Zulu Army. For example, Adrian Greaves re-examines the episode in which Lieutenants Coghill and Melvill attempted to save the regimental colors after the battle of Isandlwana and were killed in the process. Various aspects of the Battles of Isandlwana, Rorke’s Drift, Nyezane, Eshowe, Ntombe Drift, Hlobane, Khambula, and Ulundi are also analyzed. Readers of this excellent compilation, while perhaps desiring more complete references, will be rewarded with a much greater understanding of the 1879 Zulu War and of the British Army at its imperial zenith.

The United States Marines in North China, 1894-1942, by Chester M. Biggs, Jr., McFarland, Jefferson, NC, 2003, 284 pp., chronology, illustrations, maps, appendices, bibliography, index, $42.50, softcover.

U.S. Marines served in north China at various times from the 1894-1895 Sino-Japanese War until after World War II. Retired Marine Corps Master Sergeant Chester M. Biggs has used the personal papers of a number of former Marines, periodical and newspaper articles, and published books to write this volume. He begins with “Early Military Operations in North China” and “Early Marine Legation Guards.” Chapters 3 through 9 cover the antiforeigner Boxer Rebellion of 1900-1901. Marines participated in all operations in this campaign, from the Marines who guarded the legation during the 55-day siege of Peking (Beijing), to the 112 Marines in the first unsuccessful relief column, and to the Marine battalion in the force that captured Peking on August 14, 1900. An unusually high number of Medals of Honor— 33—were awarded to enlisted Marines for their bravery during the Boxer Rebellion. Marines served in north China as a stabilizing force during the 1920s and 1930s, when internecine fighting between warlords was rampant. On December 8, 1941, the Marine legation guards in Peking (including the author) surrendered to the Japanese and were marched into captivity the following month. This episode ends Biggs’s narrative, although the Marine presence in north China continued after World War II. The relatively high price of this generally well written study may prevent it from reaching a large audience.

Laurence Attwell’s Letters from the Front, edited by W.A. Attwell, Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley, UK, 2005, 222 pp., maps, illustrations, index, $39.95, hardcover.

Laurence Attwell’s Letters from the Front, edited by W.A. Attwell, Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley, UK, 2005, 222 pp., maps, illustrations, index, $39.95, hardcover.

British soldier Laurence Attwell truly was, in the words of volume editor W.A. Attwell, “one of the lucky ones.” Shortly after World War I broke out in August 1914, 26-year-old “Laurie” Attwell joined the British Territorial Army (similar to the U.S. Army Reserve). He was assigned to an infantry battalion of the 47th London Division. After training, Laurie’s unit deployed to France in March 1915. From that time until the November 11, 1918, Armistice, Laurie fought in some of the fiercest battles of the Western Front, including Festubert, Loos, Vimy Ridge, Somme, Ypres, Messines, Menin Road, Bourlon Wood, and Cambrai. Laurie, a keen observer and sensitive writer, wrote over 150 descriptive and perceptive letters to his mother and siblings during the war. They form a remarkable chronicle of a frontline World War I British soldier, shedding great light on a form of warfare and trials and tribulations in combat unimaginable almost a century later.

Resurrection: Salvaging the Battle Fleet at Pearl Harbor, by Daniel Madsen, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2003, 264 pp., illustrations, map, notes, bibliography, index, $36.95, hardcover.

The Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, was a cataclysmic event of unparalleled proportions and far-reaching repercussions. Of the eight U.S. Pacific Fleet battleships moored in Pearl Harbor that infamous morning, three were sunk, another capsized, and the others were seriously damaged. Three light cruisers, three destroyers, and many other ships were also sunk or damaged. While many accounts have been written of this disaster, very few have covered the “aftermath of the attack and the salvage of the ships”—the subject of Daniel Madsen’s well-researched and interesting study. Reacting quickly, the Navy established the Base Force Salvage Organization, led initially by Commander James M. Steel, to raise the sunken ships off the bottom of Pearl Harbor. The Navy engineers, salvagers, divers, and other damage control personnel worked prodigiously, away from the limelight of the Pacific war, to resurrect the battle fleet. Many of the ships sunk or damaged, including some considered a total loss (such as the battleship USS West Virginia), were repaired and returned to active service. The raising, for example, of the minelayer USS Oglala in 1942 and the battleship USS Oklahoma in 1943 were remarkable accomplishments. The scores of fascinating photographs that supplement the smoothly written text highlight the magnitude of the naval damage at Pearl Harbor, the difficulty of salvage and repair operations, and the high degree of success achieved.

Aden Insurgency: The Savage War in South Arabia, 1962-67, by Jonathan Walker, Spellmount, Staplehurst, UK, 2005, 332 pp., maps, illustrations, appendix, glossary, bibliography, index, $39.95, hardcover.

Aden Insurgency: The Savage War in South Arabia, 1962-67, by Jonathan Walker, Spellmount, Staplehurst, UK, 2005, 332 pp., maps, illustrations, appendix, glossary, bibliography, index, $39.95, hardcover.

Great Britain withdrew, frequently amid turmoil, from the last of its imperial possessions in the Middle East in the late 1960s. In the British Aden Protectorate in South Arabia during the early 1960s, an insurgency was fueled by external forces. The British initially supported the royalist cause through clandestine operations. As the struggle intensified, the British reinforced the area with air and ground forces. Operation “Nutcracker,” an offensive into the scorching, desolate, and lawless Radfan area, began in January 1964. Subsequent British operations in the Radfan were of questionable success. Escalating violence and assassinations forced the British to react with small unit and special forces tactics, as well as a promise of independence. The British fought a brutal rear-guard action, involving mountain fighting and urban combat, until their final withdrawal from South Arabia in late 1967. Author Jonathan Walker is to be congratulated for his excellent research and clear prose in documenting a complicated and little known modern colonial campaign.

An Nasiriyah: The Fight for the Bridges, by Gary Livingston, Caisson Press, North Topsail Beach, NC, 2003, illustrations, maps, sources, $29.95, hardcover.

An Nasiriyah is a provincial capital in south-central Iraq. About 130 miles north of the Kuwait border, this city straddles the key north-south Highway 7/8 and contains two significant bridges. The 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines was the lead element of the brigade-sized Task Force Tarawa, and it was given the mission of seizing and holding the two bridges after they were bypassed by advancing army units. The 1st-2nd Marines crossed the line of departure on March 21, 2003, and two days later reached An Nasiriyah and found the remnants of an ambushed army logistics convoy. The fighting for the bridges was fierce, and 18 Marines lost their lives securing the objective.

The dust jacket states, “this account of the fighting is the compilation of stories told by the Marines who fought for the bridges.” This book actually seems to be a chronicle of the operation, including excerpts from participant interviews and embedded journalists’ accounts, but it is very disjointed and confusing. Military terminology is frequently used incorrectly, many abbreviations and acronyms are not explained, and there are spelling errors. There are no endnotes, documentation is inadequate, and there is no index. This book at least tried to pay tribute to the gallant Marines at An Nasiriyah.

Afghanistan Cave Complexes, 1917-2004: Mountain Strongholds of the Mujahideen, Taliban, and Al Qaeda, by Mir Bahmanyar, Fortress Series, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2004, 64 pp., maps, illustrations, bibliography, index, $16.95, softcover.

Afghanistan Cave Complexes, 1917-2004: Mountain Strongholds of the Mujahideen, Taliban, and Al Qaeda, by Mir Bahmanyar, Fortress Series, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2004, 64 pp., maps, illustrations, bibliography, index, $16.95, softcover.

The indomitable mountains and caves of Afghanistan provide natural defenses to repel foreign invaders. After the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, man-made caves, tunnels, and other underground complexes were built, mainly as supply caches and underground shelters. Author Mir Bahmanyar describes these tunnel systems and highlights the advanced weapons used by United States military forces in Afghanistan as part of the “Global War on Terrorism.” Defensive and offensive operations, and much extraneous material on the “theory of American combined arms—Battlefield Operating Systems” is also included. Bahmanyar also assesses the 1985 and 1986 battles at Zhawar Kili and sketches two more recent engagements. As with most Osprey volumes, this book contains outstanding color photographs, maps, and cutaway artwork. The largely American-built caves and tunnels were used by the Afghans with great success against the Soviets, and the Afghans continue to use them against a new foreign invader.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments