By Chuck Lyons

By the 1870s, the agitation for Irish independence, already centuries old, had spread to America. The revolutionary Irish Republican Brotherhood, known as the Fenians, began organizing thousands of Irish immigrants trained on both sides during the recent Civil War into its own army. The Fenians held mass meetings and raised funds among the many Irish immigrants residing in the United States. The organization also began work on a secret weapon.

The Fenians already had invaded British-controlled Canada on four separate occasions, hoping to ransom whatever parts they conquered in exchange for the liberation of Ireland. The invasions failed miserably, and the Fenians, looking for another way to twist the tail of the British lion, turned their attention to the development of a new and unique weapon—the submarine. They hoped to develop a sub that could be launched from land or from a larger ship, approach within firing distance of a British warship, and sink it with a self-launched torpedo.

John Phillip Holland: A Naval Visionary

The man the Fenians chose to design the secret weapon was an Irish-born schoolteacher and one-time novice of the Christian Brothers holy order, John Phillip Holland of Paterson, New Jersey. Holland was born in County Clare, Ireland, in 1841, the son of a man who patrolled the county’s headlands for the British Coast Guard. Holland attended the Christian Brothers School in Ennistymon, where he was influenced by Brother Bernard O’Brien, a scientific, mechanically minded man who had invented several telescopes with mechanisms to follow the rotation of the stars.

In June 1858, Holland joined the Christian Brothers order, and in November he was assigned to the North Monastery School in Cork, where he met Brother James Dominic Burke, a fellow science teacher credited with instituting vocational training in Ireland and a man who was working on the use of electricity for underwater propulsion—an innovation that would loom large in Holland’s own future.

Holland’s main interest at the time was in ships—and in Ireland. “I was a school master in Cork, Ireland,” he later wrote, “when the [American] civil war was in progress, and about two weeks after the battle between the Merrimac and the Monitor it struck me very forcibly that the day of wooden walls for vessels of war had passed and that ironclad ships had come to stay forever.” He also realized that Great Britain, with all her many resources, would soon come to dominate the era of ironclad ships. As a loyal Irishman, Holland “wondered how she could be retarded in her designs upon the other peoples of the world and how they would protect themselves against those designs.” It was a question he would eventually attempt to answer forcefully on his own.

In 1869, while serving at a school in Dundalk, Holland designed his first submarine. Three years later, he declined to take his final vows and departed for America. He took a job teaching at St. John’s Parochial School in Patterson, and in 1876 he was introduced to the Fenian Brotherhood by his brother Michael, who had been involved with the Irish separatist movement in Ireland and had narrowly escaped a British crackdown by immigrating to the United States. The Fenians agreed to finance Holland’s scientific investigations from its “skirmishing funds” in the hope of developing a new weapon with which to attack the British.

Past Attempts at Creating a Submarine

Although Holland has been called “the Father of the Submarine,” he was not the first to dream of underwater travel. The idea went back as far as the third century bc, when Greek thinker and mathematician Archimedes discovered the laws of floating bodies. A practical design did not appear until 1578, when a British inventor proposed a boat that could be submerged and rowed underwater. A similar design was tested in 1605, and in 1620 a Dutch inventor made brief underwater trips in a leather-encased rowboat. In the 1770s, American inventor Davis Bushnell developed a hand-propelled, one-man submarine, the Turtle, which was launched during the American Revolution and used unsuccessfully to attack the British battleship Eagle in New York harbor.

Robert Fulton, inventor of the steamship, also toyed with submarine ideas in France and on the Hudson River around 1800. Fulton’s designs were equipped with a hand-turned screw propeller for undersea operation and a sail for surface use. Work was also begun in the early 19th century on a submarine intended to rescue Napoleon Bonaparte from his exile on St. Helena, but the emperor died before the plan could be executed. During the Civil War, the Confederacy built and used four small submarines, one of which, the Hunley, blew up the Federal warship Housatonic in Charleston harbor by ramming it with a torpedo fixed to its bow. The early subs were difficult to maneuver, slow-moving, and extremely dangerous for those operating them. (The entire eight-man crew of the Hunley perished after blowing up the Union ship.) “A submarine boat in order to be effective,” Holland wrote, “must steer straight underwater, act quickly, and attack from a distance.” His design, he claimed, did all those things.

The Lessons of the Holland I and the Fenian Ram

Holland’s first design, called Holland I, financed by Fenian skirmishing funds, submerged to a depth of 12 feet in June 1878 while Fenian officials looked on. It was a one-operator vessel, 14 feet, 8 inches long, three feet wide, and displacing 2.5 tons. It had been built in New York City and Paterson and launched from a horse-drawn wagon. Although Holland considered the design a failure, the Fenians were impressed enough to extend funding for Holland’s second design.

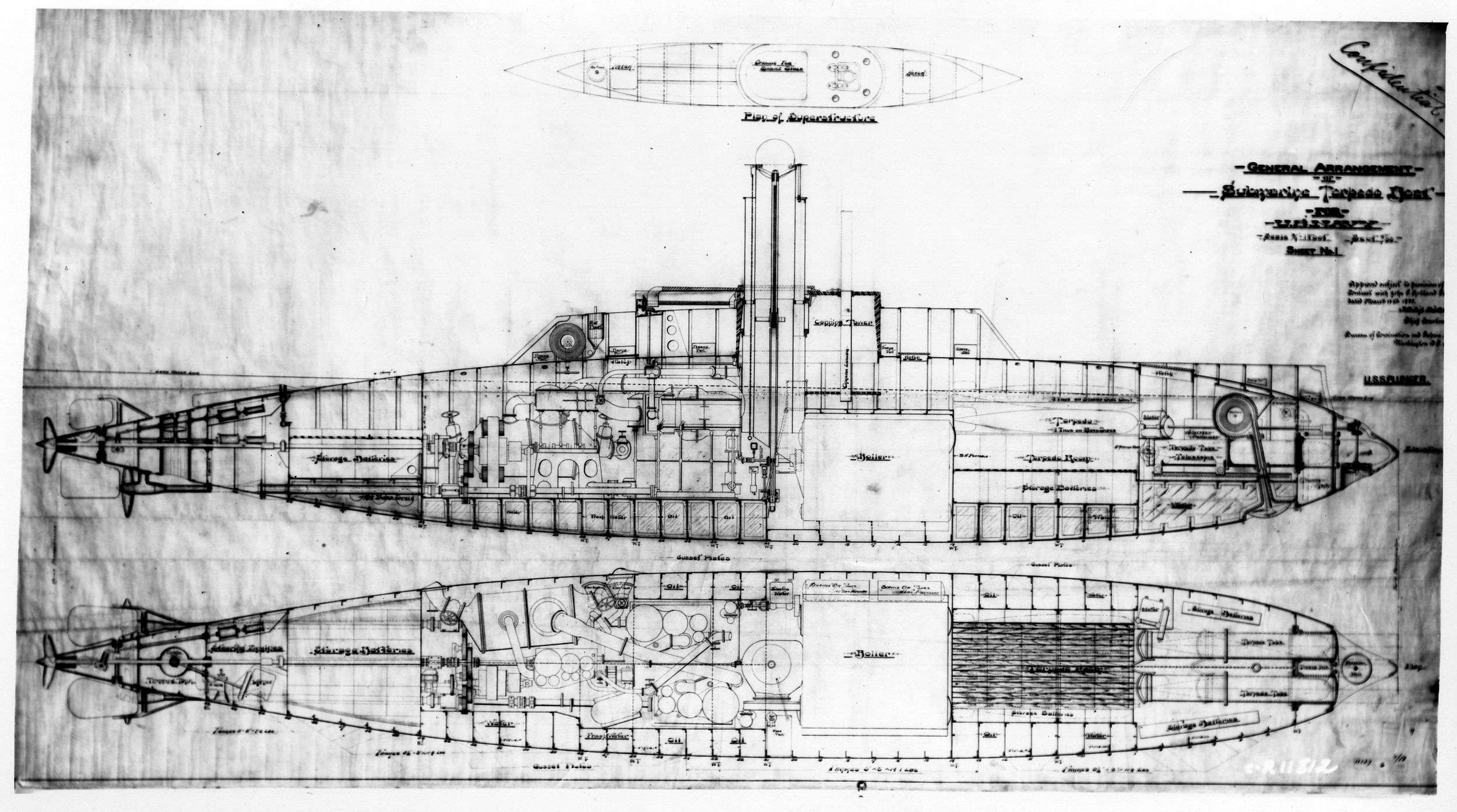

Construction of the second vessel began on May 3, 1879, at the Delameter Iron Works at the foot of 13th Street in New York City. The new sub, dubbed the Fenian Ram, was launched in April 1881. It was 31 feet long, nine feet wide, and it displaced 19 tons. Further tests were begun in June, with its first dive at dockside reaching a depth of 14 feet. On its second dive the next day, the vessel stayed submerged for 2.5 hours.

Holland had learned two things from that first design that he later applied to the Fenian Ram. First, he learned that the idea of using air purifiers, which had been intended to supply air for the crew, was impractical. “It was simply folly,” he later wrote, “to be bothered with either respirators or air purifying [equipment]. They need lots of attention that can’t be spared for them, and a fair supply of compressed air, that can be easily stored, render them superfluous.” He also learned that his original idea of opening the hatch and firing a torpedo from the top of the submarine was impractical and would not work.

The Fenian Ram had two additional features that were to loom prominently in future submarine design and building—the use of water ballast to submerge the craft and the use of horizontal rudders to dive. Holland claimed that the Ram could remain submerged for up to three days and shoot a 100-pound torpedo 50 or 60 yards underwater and as far as 300 yards above water. During the tests, the submarine reached depths of 45 feet and surface speeds of nine knots.

Specifications of the Fenian Ram

The Ram was designed to carry a three-man crew, and a large flywheel on each side of the ram operated a compressor mounted over a high-pressure air tank. Compressed air held in the ship’s tapered bow and stern ensured buoyancy. Water ballast compartments separated the compressed air from the crew’s central compartment. The sub was propelled by a 20-horsepower Brayton gasoline engine for surface use, an engine that represented a technological breakthrough by being small enough to fit into a submarine. It would allow the boat to reach a speed of up to eight knots. For underwater propulsion, the Ram used an electric motor that was also used to recharge the vessel’s battery.

An operator sat above the engine and worked two joystick levers, the left controlling the rudder, the right the diving planes. An engineer regulated the valves, observed the various gauges, and was able to “blow” the fixed-ballast tanks if an emergency required it. The third crew member was a gunner who operated the submarine’s pneumatic gun, an 11-foot-long, nine-inch-diameter tube that ran through the forward ballast tank and compressed-air compartment and fired a six-foot-long torpedo with a 400-pound burst of compressed air.

Firing the torpedo required the gunner to loosen the tube’s heavy iron breech, load the torpedo, shut the breech, crank open the bow cap of the tube, and loosen the compressed-air charge by means of a balance valve. He then had to crank closed the bow cap and blow the tube clear of the water that had flooded it, forcing the water out of the tube and into the forward ballast tank. “The Ram was submerged,” Holland later wrote about a successful firing, “to a depth which put the bow of the pneumatic gun about three feet below the surface. The projectile cleared the muzzle by eight to ten feet. Then, it leaped out of the water and rose sixty to seventy feet in the air to plunge downward and buried itself irretrievably in the mud.”

As its name suggested, the Fenian Ram could also be used as a ram, something Holland himself discovered during tests. “We had a partial demonstration once by running into the end of our pier at about six miles speed owing to my poor steering or forgetfulness of the tide,” he wrote. “We split a 12-inch spile and lifted a horizontal tie having a load of four feet deep of stone ballast over it and hurt nothing but the engineer’s respect for good English. The boat was strong enough to endure it.” Tests also revealed that the boat’s compass was useless when the Ram was submerged. To successfully navigate, the sub was required to surface, take a compass bearing, and submerge again. It was virtually undetectable while submerged, Holland wrote, with air bubbles from its exhaust all but invisible except in dead-still water, where they could be seen on the surface several feet behind the Ram.

The Fenian Ram Falls Victim to Legal Disputes

In November 1883, after the submarine had been built and tested, but before the submarine could be used in battle, a dispute erupted between Holland and the Fenian Brotherhood over use of funds that had financed Holland’s first two designs and a third submarine that was then being developed. Members of the Brotherhood accused Holland of misusing the funds, and they actually filed a lawsuit to enjoin the spending of additional funds on Holland’s projects. Holland in turn claimed that George Brayton, who had supplied the Ram’s engine, had asked more for the engine than he had originally expected, and that he was considering court action against Brayton.

Concerned that the pending legal actions would result in attachment of Fenian property, a number of Fenians using a forged pass carrying Holland’s signature, entered the dock area where the Ram was tied, and seized the Ram and a 16-foot model docked nearby. A tug towed the two vessels out of New York harbor and into Long Island Sound, where the model sank in choppy water. The group took the Ram to New Haven, Connecticut. Once there, they discovered that they did not have the knowledge needed to operate it. Holland, who of course did have the knowledge, angrily refused to help.

The Fenian Ram was never used in battle. It languished in Connecticut, its engine eventually removed to a brass foundry, until 1916, when the vessel was taken to Madison Square Garden in New York City and displayed to raise funds for victims of the Irish Easter Uprising. Later, the vessel moved to the grounds of the New York State Marine School and then to West Side Park in Paterson. Eventually, the Fenian Ram was transferred from the park to the Paterson Museum at 2 Market Street in Paterson, where it remains today.

After the disagreement with the Brotherhood, Holland gave up teaching, worked with a pneumatic gun company, married, and had a child who died in infancy. In 1888, he won a United States Navy competition for the design of a functioning submarine. No contract was awarded, however, and Holland took a job as a draftsman. He won a similar Navy contest in 1893 but again no contract was awarded, and he turned his talents to designing a flying machine. His flying machine might well have worked, experts later said, but the Wright Brothers succeeded before he could complete his machine. Holland eventually was involved in creating other submarine designs, including one capable of 22 knots, and when he died of pneumonia at age 73, he held 23 U.S. patents involving submarines and submarine warfare. Ironically, Holland’s designs eventually were picked up by the British Navy, which commissioned several submarines, including one named Holland I.

Forty days after Holland’s death in 1914, Germany’s U-9, a 450-ton submarine manned by a crew of 26, sank the British cruisers Aboukir, Cressy, and Hogue, sending 36,000 tons of enemy shipping to the bottom and 1,400 men to their deaths. The era of the modern submarine had begun.