By Glenn Barnett

HMS Warspite fought in two world wars and several major battles against a combination of enemies to become the most decorated ship ever to serve the Royal Navy.

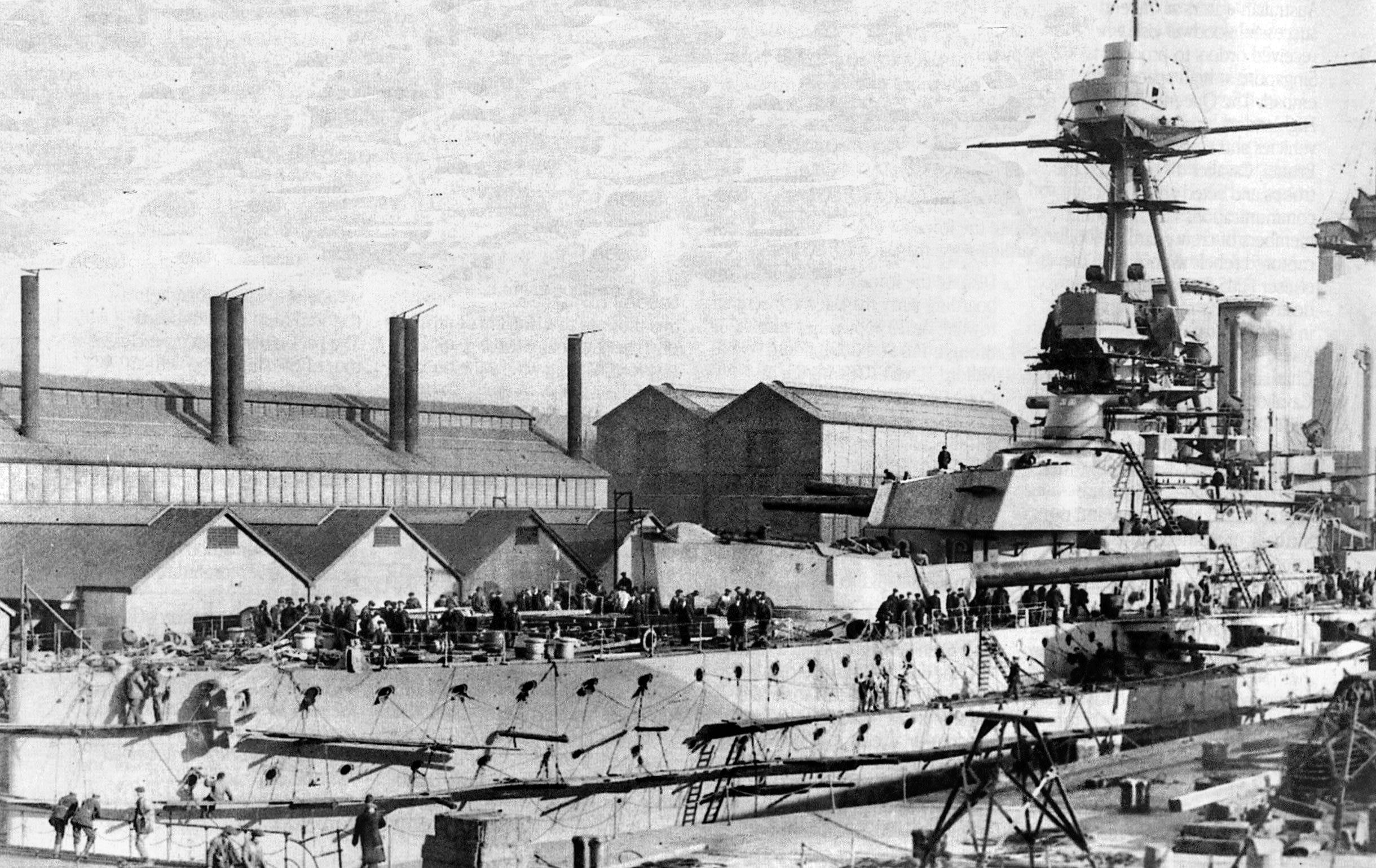

A naval arms race between Great Britain and Germany preceded the First World War. To stay ahead of their rival, the British undertook to build five new “Super-Dreadnought” battleships in 1912—the Queen Elisabeth, Malaya, Barham, Valiant, and Warspite. They were known as the Queen Elisabeth class and featured two important improvements over previous capital ship designs. Both these changes were strongly pushed by the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill.

First, they would mount eight new, secretly developed and untried 15-inch guns in four turrets to replace the standard 13.5-inch guns of their predecessors of the Iron Duke class. The United States and Japan were each developing a 14-inch naval gun but a 15-incher had never been mounted on a ship.

Secondly, they would run on fuel oil rather than coal. At the time, using this “foreign” fuel was a hard sell, though some destroyers were already using oil successfully. Oil had to be imported from far away Persia, while coal was mined on British soil by British workers.

Coal was unwieldy, dirty, and labor intensive, while oil, taking up less room, could be pumped from tank to tank or directly into the boilers to help keep a ship’s weight balanced while freeing up manpower for the guns. Churchill won the argument.

Steaming at 24.5 knots under ideal conditions, the “Queens” were known as the first of the “fast” battleships. The most successful of the Queen Elizabeth class, by far, would be HMS Warspite—nicknamed the “Spite.”

Despite the cutting-edge innovations, the “Queens” would retain at least one anachronistic feature from the days of wooden sailing ships. They were fitted with an “Admirals Walk” attached to their stern. This shaded platform was mounted outside the ship’s hull and allowed a fleet admiral a place to take the air or hold private conversations during conferences while in port. (Photos in the November 20, 1939, edition of Life magazine featured Warspite’s outdated “stern walk.”)

Warspite was commissioned in March 1915. Following sea and gunnery trials, she joined the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow, the great Scottish anchorage, as war was raging across Europe.

After a German hit-and-run naval bombardment of the ports at Lowestoft and Yarmouth on the English coast, the British people were furious that the Navy had let the raiders get away. As a result of public anger, Warspite and her sisters were assigned to a rapid-response force commanded by Vice Adm. David Beatty. They were based at the Firth of Forth near Edinburgh, Scotland.

While there, Beatty learned that the German fleet had put to sea and was determined to engage it; he could not wait for the slower and older battleships at distant Scapa Flow to join him. In the grand tradition of Horatio Nelson, he headed directly for the enemy and engaged, firing the first salvos of the Battle of Jutland.

Warspite—along with Malaya, Valiant, and Barham and their 15-inch guns—outmatched the German battleships that mounted smaller 11- and 12-inch guns. But German fire control was more accurate. During the fight, Warspite’s steering jammed from damage caused by a German shell and she helplessly tracked twice in wide circles before righting herself.

While unable to steer, she became the target of the closest German battleships and was hit 15 times, killing 14 men and wounding 32 more. The ship was a shambles of debris and wreckage.

The shells she took saved the crew of the badly damaged and burning armored cruiser Warrior, which had been the target of German guns until they switched their fire to Warspite. Warrior was able to limp away and 743 of her surviving crew were taken off and saved before she foundered.

When Warspite’s crew regained steering control, she came out of her turns but was headed straight for the German line. Worse, her engine room was flooding, which caused speed to drop from 25 to 16 knots and only her forward turrets could be brought to bear.

By this time, however, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe’s main battle fleet, rushing from Scapa Flow, had come up and began pouring heavy fire on the German fleet, which turned to the south and fled. When the battle ended, Warspite, in danger of sinking, was escorted to the Royal Naval Dockyards at Rosyth in the Firth of Forth for repairs.

Returning to service, she would not fight again but would spend the rest of the war at Scapa Flow. At war’s end, she steamed out to escort the surrendered German fleet to anchor there.

Her first war was rough on Warspite. She had run aground once, collided with other Royal Navy ships three times, and took severe damage and casualties at Jutland. But the “Great War” was only a prelude of things to come.

During the interwar period, Warspite served with the Atlantic Squadron and in the Mediterranean Sea. In 1924, and again in 1934, she underwent modernization. Her two funnels were removed and replaced by a single larger one. Her torpedo tubes were removed, making room for seaplanes, along with their launcher, crane, and hanger. Torpedo bulges were installed along her hull.

New, lightweight engines increased endurance and decreased weight and fuel consumption. The weight savings was used to add additional armor and new anti-aircraft guns. When her second refit was complete in 1937, she was, for a short while at least, the most powerful ship afloat.

When World War II began, Warspite was at Alexandria, Egypt. Disaster called her back to home waters when a U-boat navigated through the defenses as Scapa Flow and sank the battleship Royal Oak. She made it as far as Gibraltar before new orders sent her to Canada.

Arriving at Halifax, Nova Scotia, she was assigned to escort a convoy of 30 merchant ships to Britain. In December, after the battleship Nelson was damaged by a magnetic mine, Warspite took up her duties as flagship of the Home Fleet.

In April 1940, the Germans invaded Norway, and Warspite was dispatched immediately to the Norwegian city of Narvik, an important port for the export of Swedish iron ore. This valuable industrial resource was vital to both sides.

A force of 10 German destroyers landed 2,000 mountain troops at Narvik on April 9. The destroyers were to refuel and return to Germany, but the tanker assigned to the task was blown up by British destroyers. A tanker already in port was pressed into service, but its improvised pumping system was inadequate to the task. Only two destroyers had been refueled by the time five British destroyers arrived the next day.

The British destroyers steamed into Narvik harbor on April 10 and began firing on every German ship they could find. Two of the attacking British ships would be sunk, as well as two of the enemy’s destroyers. By the time the British flotilla left Narvik, reinforcements, including Warspite, had arrived to box the Germans in.

The German situation at Narvik was desperate. The remaining eight destroyers were low on fuel and ammunition. They tried to hide deep within the Narvik fjord, but Vice Adm. William “Jock” Whitworth aboard Warspite gathered a force of nine destroyers and proceeded to attack the Germans on the 13th.

Warspite’s raid was to be supported by aircraft from the carrier HMS Furious, but foul weather negated their usefulness. Instead, Warspite relied on her own Fairey Swordfish float planes. As the battleship and her destroyers steamed toward Narvik, one of her planes spotted and sank U-64. It was the first time that an aircraft sank a submarine.

Charging into the fjord, Warspite and her escorts, guided by the float planes, sank or severely damaged the eight remaining German destroyers. Perhaps boasting about his insistence on mounting untested big guns on the ship in 1912, Churchill wrote, “The thunder of her [Warspite’s] 15-inch guns reverberated among the surrounding mountains like the voice of doom.”

Despite several torpedoes fired at Warspite, they all missed due to adroit steering and she escaped unscathed. Warspite vacated the harbor to gain maneuvering room against U-51, a U-boat known to be in the area, as well as any German bombers that might appear. She would remain in Norwegian waters providing shore bombardment until April 24 when she was recalled to Scapa Flow.

Back in port, Warspite’s sailors found that the news of the (temporary) victory at Narvik had preceded them and the ship’s name was on everyone’s lips. It was a spot of good news in a war that was not going well.

The battleship was hurriedly refueled and resupplied before being ordered to the Mediterranean. Even as she steamed south through the Atlantic, news was received that France had been invaded. By the time she arrived in harbor at Alexandria in Egypt, the Battle of France was almost over.

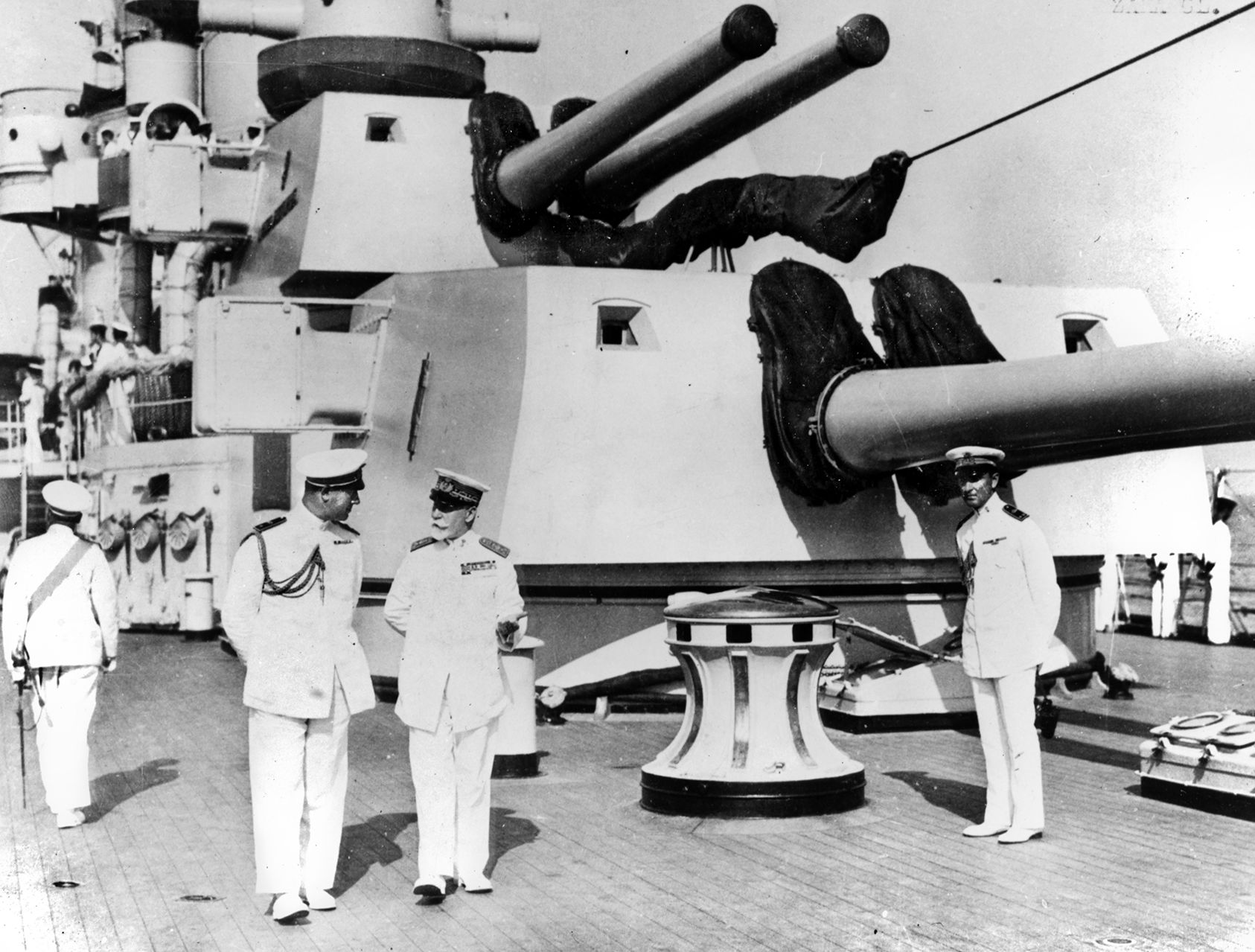

In Alexandria, the British Naval Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean, Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham, was piped aboard as he transferred his flag to his fastest ship, and Warspite became the flagship of the British Mediterranean fleet.

There were three major fleets in the Mediterranean Sea: French, British and Italian. The allied French and British armadas intimidated the Italians into neutrality but, with Adolf Hitler’s sensational Blitzkrieg through France, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini felt emboldened. Italy declared war on an almost helpless France and sided with Germany. With the French Navy paralyzed by defeat, the British stood alone against a formidable Italian fleet.

The British Admiralty had little to spare from their life-or-death struggle against U-boats and commerce raiders in the Atlantic but were compelled to take on the Italian Navy, the Regia Marina, as well. First however, the Vichy French fleet had to be prevented from joining the Nazis. A British squadron based at Gibraltar fired on French ships at the port of Mers-el-Kébir in Algeria, killing nearly 1,300 French sailors. Frenchmen of every stripe were enraged at “perfidious Albion,” their former ally.

At Alexandria, Cunningham wanted to reach a solution that didn’t involve firing on the French ships then in port, including the battleship Lorraine and four cruisers. He negotiated with the French Admiral René-Émile Godfroy. With skillful diplomacy—and the implied threat of Warspite’s guns—a tenuous but amicable solution was reached.

No sooner was the French squadron at Alexandria secured than Cunningham, on Warspite, led his squadron to sea on July 7 to escort a convoy steaming to Alexandria from Malta. In all, he commanded one aircraft carrier (the aging Eagle), three battleships, five light cruisers, and 16 destroyers of various worth.

At the same time, the Italians were sending a convoy of supply ships south to Libya. They were guarded by a considerable escort including two battleships, six heavy cruisers, eight light cruisers and 16 destroyers, commanded by Vice Adm. Inigo Campioni.

Scout planes and submarines from both sides revealed the presence of the other. Cunningham steered his ships between the Italian fleet and their base at Taranto in the arch of the Italian boot. He hoped it would force them to fight.

For their part, the Italians hoped to lure the British into their home waters where submarines and shore-based bombers could reach them and aid in the battle. As it was, the three branches of the Italian military could not coordinate their actions. The British would not be lured to a spot where the submarines were waiting for them and 126 Italian bombers flying at 12,000 feet, scored only one hit—on the cruiser Gloucester—before the two fleets met.

On the morning of July 9, the screening cruisers made contact with each other. In this contest the British light cruisers, mounting 6-inch guns, were no match for more numerous Italian heavy cruisers firing 8-inch guns.

Admiral Cunningham ordered Warspite to the aid of his cruisers, causing the Italians to flee her 15-inch guns behind a hastily laid line of smoke. As the Italian cruisers withdrew, the two battleships Giulio Cesare (Julius Caesar) and Conte di Cavour advanced on Warspite.

The other two British battleships, the unmodernized Malaya and the disappointing Royal Sovereign, were too slow to engage in the brief battle (Malaya would get off one ineffectual salvo).

In effect, Warspite stood alone against the two onrushing Italian battleships. At about 4 p.m., both sides opened fire at extreme range. Giulio Cesare soon straddled Warspite with near misses. When Warspite fired a salvo at 26,000 yards, one shell hit the Italian battleship Giulio Cesare. The hit was perhaps the longest naval artillery shell fired at a moving target ever to find its mark.

The shell hit Giulio Cesare in her rear funnel and exploded, causing almost 100 casualties. Fires and smoke fumes raged through the boiler rooms, chasing out the coughing crew and putting half the boilers temporarily out of action. Speed was suddenly reduced from 27 to 18 knots. As a result of this one hit, Admiral Campioni ordered his ships to disengage. The Battle of Calabria was over.

In his dispatch to the Admiralty, Cunningham wrote, “Warspite’s hit on one of the enemy battleships at 26,000 yards range might perhaps be described as a lucky one. Its tactical effect was to induce the enemy to turn away and break off the action, which was unfortunate, but strategically it probably has had an important effect on the Italian mentality.”

For the next three months, Warspite engaged in convoy protection and shore bombardment in support of British ground forces while successfully fending off the occasional air attack. Her one lucky hit on Giulio Cesare had the effect of keeping the Italian fleet in port. In August she was ordered to dry dock in Alexandria where her peacetime gray paint was finally covered over with war-time camouflage.

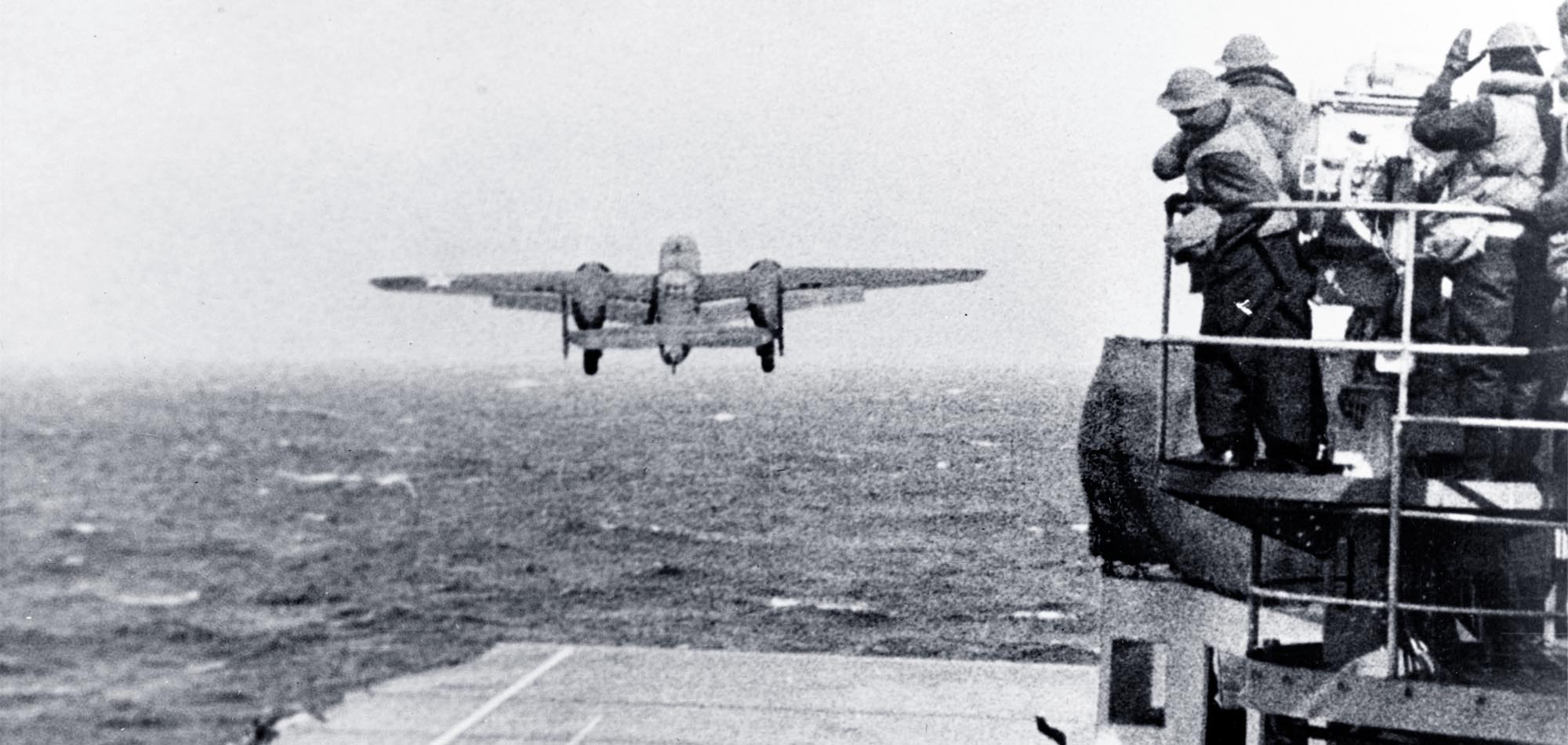

On November 6, Warspite steamed in radio silence with the bulk of the Mediterranean fleet in convoy to Malta. There, on the evening of the 11th, the aircraft carrier Illustrious and her escorts, four cruisers, and a screen of destroyers, quietly detached from the convoy to carry out an air raid on the immobile Italian fleet at Taranto. The rest of the British squadron stood in readiness as distant cover. It was an anxious night for all involved.

Illustrious, whose Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers sank one Italian battleship while seriously damaging two others plus a heavy cruiser and two destroyers, rejoined the fleet at dawn the next day exultant with victory. The sinking of Italian capital ships in their home port would inspire the Japanese to do the same at Pearl Harbor.

In mid-January the Luftwaffe added its weight to the Italian air attacks on Malta. On January 10, 1941, Stuka dive bombers zeroed in on Illustrious as she was in convoy bound for Malta. Warspite stayed close to provide anti-aircraft support as the vulnerable aircraft carrier limped into the port of Valletta. During the melee, Warspite was only hit once with a glancing blow that ricocheted off an anchor.

Hitler, besieged by Mussolini’s pleas for help, agreed to support the Italians, who were being manhandled by the enraged Greeks following a botched Italian invasion. The German plan was to knife through the Balkans in March in order to reach Greece, prop up his friend, and undermine the British position there.

As part of the deal, the Italian fleet was coerced into disrupting the troopships between Egypt and Crete that were strengthening the British positions. Alerted by a reconnaissance plane that had spotted Italian cruisers and destroyers heading toward Crete, Admiral Cunningham, aboard Warspite, ordered the Mediterranean Fleet to sea on the evening of March 27.

When the Italian fleet was sighted south of Crete by his screening cruisers, Cunningham increased speed and changed course to intercept. It is likely that he wanted to challenge another Italian battleship to slug it out, but Warspite was having mechanical problems which restricted her speed to 20 knots.

The admiral ordered planes from the carrier Formidable to make a torpedo attack. Six Fairey Albacore biplanes responded, but scored no hits. Yet it was enough to make the skittish Italians, who had hoped to ambush some undefended troop or supply convoy, turn for home. They had not bargained on meeting up with Warspite and the British Mediterranean Fleet.

Now the two navies fought a running battle while rushing westward, the Italians in retreat. Formidable launched three more Albacore torpedo planes to target the Italian battleship Vittorio Veneto. At 4:30 in the afternoon, one of the Albacores scored a hit in the stern of Vittorio Veneto, damaging her portside propulsion shaft and slowing her speed to 15 knots. The plane and her crew gave their lives in the process.

At 7:30 p.m., another air attack left the Italian heavy cruiser Pola dead in the water, although the British were unaware of this. In the growing darkness, radar contact was made with two ships some six miles ahead. Cunningham saw an opportunity for a night attack.

He ordered Valiant, Formidable, and Barham into line behind Warspite with a screen of destroyers on either side. Running with their lights out, they quietly approached the position of the radar sighting while training their guns by the radar’s signal.

The Italian admiral, operating without radar, thought that the British fleet was 90 miles astern. He ordered the heavy cruisers Zara and Fiume, along with four destroyers, to assist the stalled Pola. Without radar they could not know of the enemy’s approach. At 2,900 yards, searchlights were turned on which illuminated Fiume. The British fired at the unsuspecting Italians at point-blank range.

Five of Warspite’s first six shells struck home. Fiume was shattered and burning when, 30 seconds later, a second salvo smashed into her again. Fiume limped into the darkness and sank within the hour. Warspite then turned her guns on Zara. Valiant and Barham added their fire to doom the second Italian cruiser.

In just 10 minutes,Warspite alone fired off 40 rounds from her 15-inch and 44 rounds from her 6-inch guns. British destroyers then finished off two of their counterparts and sank the crippled Pola. Cunningham sailed his fleet away without a scratch. In all, three heavy cruisers and two destroyers were sunk. The Battle of Cape Matapan, a resounding British victory, was over.

In April, Warspite conducted convoy-escort and shore-bombardment duties against Tripoli, Libya. In May, the Germans made their airborne landings on Crete. The Mediterranean fleet was called upon to support and then to evacuate the British troops on the island. All the while the fleet would be under intense German bombardment. Now it was the Royal Navy’s time to suffer.

While on station 100 miles west of Crete on May 22, Warspite, sailing without Cunningham, her “lucky admiral,” came under attack from waves of German planes. At 1:30 p.m., she was pounced upon by three ME 109 fighter/bombers, each carrying a 250kg (500 lb.) bomb. The mighty ship swerved to avoid them.

Two of the bombs missed but the third struck a 4-inch gun mount on the starboard aft and blew it overboard. The bomb penetrated the deck and exploded, killing 38 and injuring 31, while knocking out a 6-inch gun as well. Fires broke out and one boiler room was temporarily evacuated due to smoke. Speed dropped to 18 knots.

During the disastrous evacuation from Crete, the British lost three cruisers and six destroyers. Warspite, Barham and Formidable were damaged along with more cruisers and destroyers. To make matters worse, in the Atlantic, the HMS Hood was sunk with only three survivors that same week.

Temporary repairs were made to Warspite but more extensive work was required. She was ordered to steam to the U.S. Navy Dockyard at Bremerton in faraway Washington State for extensive repairs and the addition of advanced radar and fire control systems. Her worn-out 15-inch gun barrels would be replaced with new barrels sent from Great Britain.

The day before her departure from Alexandria, a German air raid sent a 1,000-pound bomb close enough to explode beneath her hull, causing warping in her plating. Her crew was happy to get out of the Mediterranean.

Warspite arrived in Puget Sound on August 11 and would still be there when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. When news of the attack was received, she went on full alert, her crew recalled from shore. Warspite was one of the few ships in harbor that day capable of offering resistance to an enemy attack and the only ship’s crew with combat experience. Ironically all of her ammunition had been removed and stored ashore during her reconstruction. Trucks were rushed to retrieve her precious munitions.

The next day brought news of the sinking of HMS Repulse and Prince of Wales. If the Taranto-style attack on Pearl Harbor were not bad enough, it was sobering for Warspite’s crew to realize just how vulnerable big-gunned capital ships had become.

Upon completion of her refit, rather than return to the Mediterranean, Warspite was ordered to the Indian Ocean via Australia to shore up the Royal Navy on a new front. She arrived in Trincomalee, Ceylon (Sri Lanka) on March 22, 1942. On the 27th she became the flagship of Admiral Sir James Somerville, who had once been her captain; he had only arrived in port the day before. Warspite was now the most important ship of the British Eastern Fleet.

On the very next day, March 28, the anniversary of the victory at Cape Matapan, Somerville received word from British Intelligence that the Japanese planned an air attack on Ceylon. He immediately ordered all ships out of the ports of Trincomalee and Colombo to prevent their being trapped and sunk there.

Next, he formed his meager number of ships into two columns; “Force A” consisted of the faster ships. Led by Warspite, they included the two modern aircraft carriers Formidable and Indomitable with a combined 40 fighters and 60 torpedo planes of mostly antiquated biplane designs. Not all were serviceable. There were also the heavy cruisers Cornwall and Dorsetshire, two light cruisers, and six destroyers.

“Force B” consisted of four battleships of the R class, newer than Warspite. But they had not been modernized and were slower and carried fewer anti-aircraft assets. In order not to hold back the faster ships, Force B cruised separately.

Somerville judged that the Japanese squadron would approach Ceylon from the southeast. That squadron was the world’s first aircraft carrier strike group, the Kidô Butai. These same ships had successfully bombed Pearl Harbor and later the port of Darwin in Australia.

Somerville knew that he was no match for them. He adopted a strategy of steaming southwest of Ceylon, westward during the day and eastward at dusk. Each time he cruised on a different arc to prevent Japanese submarines from lying in wait. In this way he hoped to avoid detection by Japanese air reconnaissance by day and, hopefully use his radar-equipped torpedo planes to make a night attack on the enemy.

He steamed in this manner for three days and two nights but the enemy was never sighted. With his ships running low on fuel, fresh water, and supplies, Somerville assumed the intelligence reports were faulty. He took the fleet to the secret British naval base at Addu Atoll, 600 miles south of Ceylon, to replenish.

Cornwall and Dorsetshire were detached to Colombo, while the outdated aircraft carrier Hermes, sailing with Force B, was sent to Trincomalee to prepare for a planned attack on Madagascar.

Detaching these ships was a horrendous mistake—all three would soon be sunk.

Force A arrived at Addu Atoll at noon on the fourth, and the ships immediately started to refuel and resupply. The slower Force B arrived at 3 p.m. At 4:30, Somerville received word that a Consolidated PBY Catalina had spotted a Japanese force approaching Ceylon from the southeast. At midnight, after all of the Force A ships had refueled, Warspite led them in the direction of the reported sighting; Force B would follow at 6 a.m.

For the next four days, the British and Japanese fleets tried desperately to find and destroy each other, but neither side could locate the other. Occasionally, Warspite’s radar would pick up Japanese aircraft on the edge of their screens but the Japanese were never able to find Force A.

After receiving reports of the sinking of Hermes, Cornwall, and Dorsetshire, the Admiralty and Admiral Somerville were nervous that the whole Eastern Fleet might suffer destruction at the hands of the Japanese aircraft carriers, and so, on the 9th, Warspite led Force A to the safety of distant Bombay, while Force B was sent to guard the sea lane between Africa and Madagascar. Though accused of cowardice, his decision to save his fleet from the overwhelming power of the Japanese was the right one.

By early May, Force A approached the northeastern end of Vichy-held Madagascar, where they provided distant cover for Force Z, which was assigned to occupy the capital of the island, Diego Suarez, to prevent its fine harbor from falling into Japanese hands. From there Force A steamed to Kenya to refuel and resupply.

By the middle of the month, Admiral Somerville was approached by the Admiralty and representatives of the U.S. Navy to ask if he could return to Ceylon as a diversion against anticipated Japanese attacks in the mid-Pacific. On June 5, Warspite led Force A back into Colombo harbor. Even as she docked, the Battle of Midway raged in the distant central Pacific.

Though the Kidô Butai suffered badly at Midway, the Japanese were still active in the Indian Ocean. Submarines and surface raiders roamed the huge oceanic expanse like sharks hunting prey.

There were also two Japanese merchant cruisers prowling in southern waters between Australia and South Africa. Originally built as passenger or cargo vessels, Aikoku Maru and Hōkoku Maru were fitted with eight 6-inch naval guns. They also served as submarine tenders for the subs operating around Madagascar.

On the same day that Warspite returned to Colombo, Aikoku Maru sank MV Elysia, which was ferrying troops between South Africa and Australia. With the crushing American victory at Midway, Force A was free to pursue these threats. Number One on that list was locating the two Japanese commerce raiders.

On June 12, Warspite led Force A in search of the two Japanese merchant cruisers. Their search centered on the Chagos Archipelago—a group of atolls and reefs south of the Maldives (today the home of the American naval base at Diego Garcia). The search for the enemy ships proved fruitless, as they were operating to the southeast of Madagascar at the time.

British concern about the raiders was just as much to protect the secrecy of their refueling base at Addu Atoll as to protect the lightly traveled sea lane between Australia and South Africa. Failing to find the offending Japanese raiders, Warspite and her flotilla returned to Colombo on the 18th before sailing to Kilindini on Zanzibar Island.

As Force A cruised back and forth through the Indian Ocean, Admiral Somerville led the crew of Warspite and the other ships of the squadron in fleet exercises, maneuvers, gunnery practice, and mock air attacks. The busy crewmen, competing with each other, were rewarded for their diligence with the Royal Navy’s tradition of a daily “tot” of rum. Winning gun crews might get an extra tot.

Unfortunately, Warspite was built for action in the cold climes of the North Sea. The crew suffered from the heat and humidity of the tropics, especially when buttoned up at their humid, airless action stations. Sickness thinned the ranks.

On July 21, once again in response to an American request to create a diversion, Warspite led Force A eastward across the Indian Ocean. This time they were to participate in Operation Stab, a simulated invasion of the Japanese occupied Andaman Islands off the western coast of Burma. The ruse was set to coincide with the U.S. Marine landing on Guadalcanal.

Steaming in convoy with dummy transports, Force A approached the Andamans on August 2. The mock invasion was covered by copious fake radio traffic of the kind that would later convince the Germans of an Allied landing at Calais as the real target of D-Day. Japanese scout planes approaching the convoy were identified by radar and shot down before they could guess British intentions.

Leaving the enemy in confusion as to their whereabouts, Force A was ordered to return to East Africa to participate in the invasion of that part of Madagascar south of Diego Suarez still in Vichy hands. On the way, Force A rendezvoused with the slower ships of Force B.

The invasion of major Madagascan cities occurred in September 1942. Warspite, with the battleships and aircraft carriers of the combined Eastern Fleet, stood by to offer shore bombardment if needed, but there was little resistance from the disillusioned Vichy French garrison.

The dawn of 1943 would find Warspite at Durban, South Africa. There, a new captain was piped aboard. He was Herbert Packer. In 1915, Packer had joined the ship’s company of the brand-new Warspite as a sub-Lieutenant tasked as an assistant gunnery officer. In the late 20’s he was her gunnery officer. Now he was her captain.

In April Warspite was ordered back to Britain to the delight of her crew who had by now traveled over 150,000 miles since the beginning of the war. Admiral Somerville remained behind. Steaming from Durban around the west coast of Africa, she arrived at port near Glasgow for another refit.

In early June, Warspite was back in the Mediterranean in time to join in the invasion of Sicily on July 9. Force H, to which Warspite was now attached, provided distant cover for the invasion forces. Following the landings, Force H moved to the Ionian Sea to prevent a naval response from Italy against the Anglo-American beachheads.

After refueling at Malta, Warspite was redirected to support stalled British troops on Sicily with shore bombardment. Proceeding with haste to her appointed target near the city of Catania, her steering jammed again, turning her in a tight circle to port before being brought under control. It was a problem that had jinxed her since Jutland.

Once the steering was sorted, she arrived on station and fired off 57 rounds at a point-blank range of 7,000 yards. Her destroyer escorts added their own shells to the din onshore. During the bombardment, Warspite was buzzed by three FW 109s but no damage was done.

Returning at speed to Malta that evening Warspite was alerted to threats from the air but no attacks materialized. Warspite’s “lucky admiral,” Andrew Cunningham was now the Commander-in-Chief of British naval operations in the Mediterranean. In a message to his former flagship, he referenced her dash back to Malta by noting that, “Operation well carried out. There is no question when the old lady lifts her skirts she can run.” Everafter, Warspite would be known as “The Old Lady.”

In August, diversion from war came in the form of an impromptu concert for the crew from popular entertainer Noel Coward. Then on September 1 a squadron including Warspite and Valiant slipped out of Malta to participate in Operation Sledge, which was the bombardment of the Italian mainland south of Reggio di Calabria in preparation for the allied landings. Specifically targeted were Italian gun sites. The landings took place on the 3rd and were unopposed, allowing Warspite and her squadron to return to Malta on the fourth.

By now the Italians had seen enough. Mussolini was ousted and secret negotiations were held to surrender to the Allies and become officially neutral. Allied negotiators insisted that all remaining Italian naval units steam to Malta so as not to fall into the hands of the Germans.

In the transfer of the Italian fleet, Warspite would escort two groups of Italian warships to Malta. The task reminded the ship’s company that Warspite had once escorted surrendered German ships to Scapa Flow in 1918.

On the 14th, Warspite, in company with three other battleships and two aircraft carriers, began the journey back to Britain to prepare for the D-Day invasion. Before they could reach Gibraltar, Warspite and Valiant were suddenly recalled to Italy’s coast at Salerno where the Germans had begun a vicious counterattack against an insecure Allied beachhead.

Warspite arrived on station around 11 a.m. Much time was spent assuring that the ship had the right targeting information as gunnery officers visited shore and other ships to verify that the big guns did not hit the threatened beachhead. By 6 p.m., the 15-inch guns opened up on German positions. When darkness fell, the bombarding ships ceased fire and withdrew.

The next morning at 8:30, firing began again; all the while the off-shore fleet was under German air attack. By 2 p.m., Warspite ceased firing and began to slowly weave her way seaward through the cluster of other ships that were supporting the landings. During this maneuvering she was attacked by a dozen low-level FW 190 fighters. The crew successfully warded off these attacks.

However, no sooner did the FW 190s clear the area than the contrails of a flight of D0 217 K-2 bombers were sighted at 20,000 feet. Each bomber was fitted to carry one FX-1400, commonly called the “Fritz X” glide bomb, that were designed to be guided to their targets using radio control by aimers in the mother craft. Three of the bombs were aimed at the slow-moving Warspite.

These glide bombs were not toys. One of them had already sunk the Italian battleship Roma as it was cruising to surrender at Malta. Now it was Warspite’s turn to be targeted. The first bomb struck on the port side at the funnel and penetrated six decks before exploding against the double hull. The blast and hull breach flooded the boiler rooms, knocking out all power to the ship.

A second bomb narrowly missed amidships on the starboard side. It exploded and ruptured the torpedo bulge, which took on more water. The third bomb missed astern and did no damage. The blast of the first bomb killed six crewmen and injured several more, while the ship took on 5,000 tons of seawater that caused her to list five degrees to starboard.

As if on cue, the steering jammed and caused Warspite to track in impotent circles dangerously close to a German mine field until she glided to a stop. Her boilers were damaged beyond use so she could not communicate, use radar, steer, or aim her guns.

Using semaphore flags, Captain Packer ordered a tow. Soon, both U.S. and British fleet tugs arrived to rig hawsers for towing. Making no more than four knots, and with tow ropes repeatedly snapping, Warspite made slow progress away from Salerno. Meanwhile, the crew was able to get the ship’s two diesel dynamos moving, powering the pumps and preventing further flooding.

As she approached the Straits of Messina, the swift southward current overpowered her tugs and all but one of her hawsers parted. Warspite went through the straits crab-like, sideways. Once out of the rushing current, the tugs reattached their lines and safely towed the helpless Warspite to Malta, arriving on the 19th. War-torn Malta’s limited repair facilities did the best they could to patch up the “old lady.” On November 1 she was sent on to the drydock facilities at Gibraltar where she arrived, still under tow, on November 12.

Warspite underwent repair in Gibraltar until March, by which time most of her crew had been transferred to other ships and a newly conscripted crew assigned to her. She then sailed in convoy back to Britain and docked at the repair yard at Rosyth, where she had been repaired after the Battle of Jutland. The aging ship wasn’t so much repaired as “patched up.”

A heavy cement caisson was placed over the hole in her hull to staunch a persistent leak, but one of her boiler rooms was too far gone to repair and was left off line. Her 6-inch guns were removed to offset the weight of the heavy caisson. One of her aft 15-inch gun turrets could not be made to swivel, and the steering problem that had plagued her the entire length of her service was still a puzzle.

Nevertheless, she was still a powerful gun platform. In May 1944 she was assigned to Bombardment Force D that was to provide fire support for the troops landing at Normandy on D-Day. Ship and crew underwent gunnery exercises with the other battleships and cruisers assigned to this force.

At 5 a.m. on June 6, Warspite was given the honor of firing the first shot on D-Day. She opened up on a German artillery battery at Villerville, behind Sword Beach. A feeble German response came quickly. Three Motor Torpedo Boats (known as E boats) were ordered to attack what were reported to be landing craft at Normandy.

Leaving their base at Le Havre, the torpedo boats encountered an Allied smoke screen. When they cleared the smoke, the terrified Germans found themselves facing not landing boats but six battleships and heavy cruisers with their huge guns. They quickly fired off 18 torpedoes at long range and retreated back into the safety of the smoke. One of the torpedoes narrowly missed Warspite while another hit and sank the Norwegian destroyer Svenner.

Warspite also came under fire from a shore battery. Shells straddled the ship with near misses. The captain ordered her moved to another position to throw off the aim of the German gunners. For the rest of the day Warspite and the other bombardment ships supported infantry ashore by firing at German batteries until they were silenced. In the evening she moved four miles off shore and anchored for the night.

The next day she was back in action firing her still-functioning guns at the enemy. In all, Warspite fired 334 of both high-explosive and armor-piercing shells. That evening she sailed to Portsmouth to replenish her magazines.

She would return to action on the 9th. This time she was assigned to a position opposite the American landing site at Utah Beach, relieving the USS Nevada, which had run low on ammunition. She fired blind at a reported German artillery position and drew praise for her marksmanship from American commanders on the ground.

On the 10th, the Old Lady was on standby most of the day before firing on an artillery battery. That evening Nevada returned to her station, so Warspite moved over to support British forces at Gold Beach. The next day, she would fire into some woodlands where a number of panzers were reported hidden. The ship was again commended for her shooting by officers on the ground.

Once more she returned to Portsmouth for more ammunition but for the second time in her long life her 15-inch gun barrels were worn out. To get new ones she would have to steam to Rosyth in Scotland. To do so, she traversed the Straits of Dover that a British capital ship had not done since the beginning of the war. At 4 a.m., German guns near Calais fired on her in the dark but missed.

Having successfully cleared the Channel, she steamed northward along the eastern coast of England. She was near Harwich when she struck a German influence mine on her port quarter. The ever-problematic steering jammed again and the port propeller shafts, bent from the impact, seized up entirely. Headway could only be made by using first one and then both starboard props. A growing list to port was corrected with counter flooding, but she was still taking on water.

The huge battleship could only make seven knots as she limped into the Firth of Forth under her own power at 11 a.m. Two of Britain’s newest battleships, Anson and Howe, were anchored there. As Warspite passed, their ship’s companies assembled, lining the decks and cheered the Grand Old Lady, envious of her storied exploits. There may never be another ship with a battle record like the legendary Warspite, and she wasn’t done yet.

At Rosyth, her worn-out gun barrels were once again replaced. Instead of the time-consuming process of removing her warped propulsion shafts for straightening, efforts were made to straighten them in position so that she could return to the war quickly. The result left the outboard starboard shaft in good condition and the inboard shaft in fair condition.

On the port side, the inboard shaft still wobbled and the outboard shaft was still “seized solid.” When she was finally released from the dockyards, she could only cruise at seven knots, and still only three of her four turrets could rotate. Predictably, the steering defect still plagued her. Though no longer a frontline ship of war, she was back on duty.

At this stage of the war, it did not matter. The German and Italian fleets were a distant memory. There would be no more duels between the big-gunned battleships except in the Pacific. All of the ocean’s big gun ships, now eclipsed by aircraft carriers, were relegated to shore bombardment. That is what Warspite was again called upon to do.

After gunnery practice with the new barrels, Warspite gingerly moved to the still Nazi-occupied city of Brest, France. There on August 25, she opened fire on shore batteries that housed 280 mm (11-inch) guns. In all, she expended 213 shells on various targets before slowly moving on to Le Havre. There she fired her guns again in support of a British advance.

After refueling and rearming at Ports-mouth, Warspite crossed the Channel once again in late October. This time she and the monitors Erebus and Roberts, with their own 15-inch guns, were to support Allied efforts to clear the Scheldt River estuary of its persistent German garrison in order to open up the port of Antwerp to Allied supply ships.

They slowly worked their way up the estuary following the minesweepers. On November 1, beginning at 8:20 a.m., Warspite and the monitors used their big guns to clear the way for amphibious landings.

Throughout the day, Warspite fired another 353 shells at targets of opportunity on Walcheren Island. The shelling of enemy positions ceased at twilight and the aging ship slowly pulled away from her firing position and put out to sea.

Since D-Day, she had fired over 1,500 rounds of 15-inch high-explosive and armor-piercing shells at the Germans. Her barrels again showed considerable wear. She had fired her last shot. The sputtering remains of the European war moved inland. For Warspite, the Grand Old Lady of the Royal Navy, her work was done.

At war’s end there were voices in Britain that advocated turning the “old lady” into a museum to share her story with future generations. But the country was exhausted from war and funds would be difficult to find. Instead, in July 1946 she was consigned to the wrecking yard to be broken up and sold off as scrap. It was the fate of almost all of the ships from this titanic war.

But Warspite refused to go quietly. In 1947, after having her guns and electronics removed, she was being towed to the wrecking yard during an unexpected storm. The hawsers parted from her towing tugs and she ran aground on the coast of Cornwall. It would be late 1950 before she could be refloated and resume her last journey.

Pieces of her are still on display at various places throughout Britain, as tribute to her contributions to King and country in two wars. Her 15 battle decorations, the most of any Royal Navy ship in history, are a proud memory.

An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that HMS Warspite was at Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1944, the day of the Japanese attack.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments